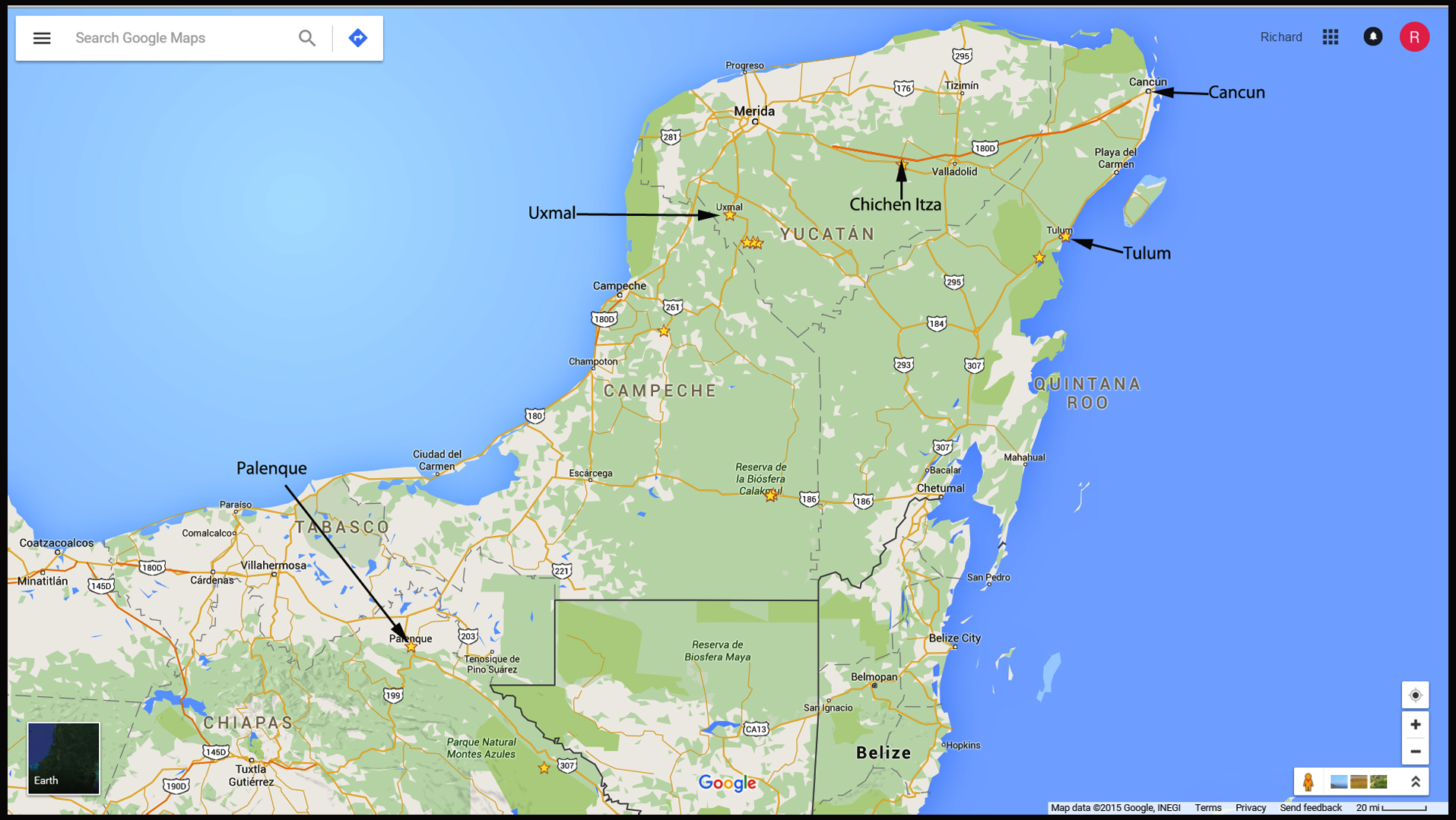

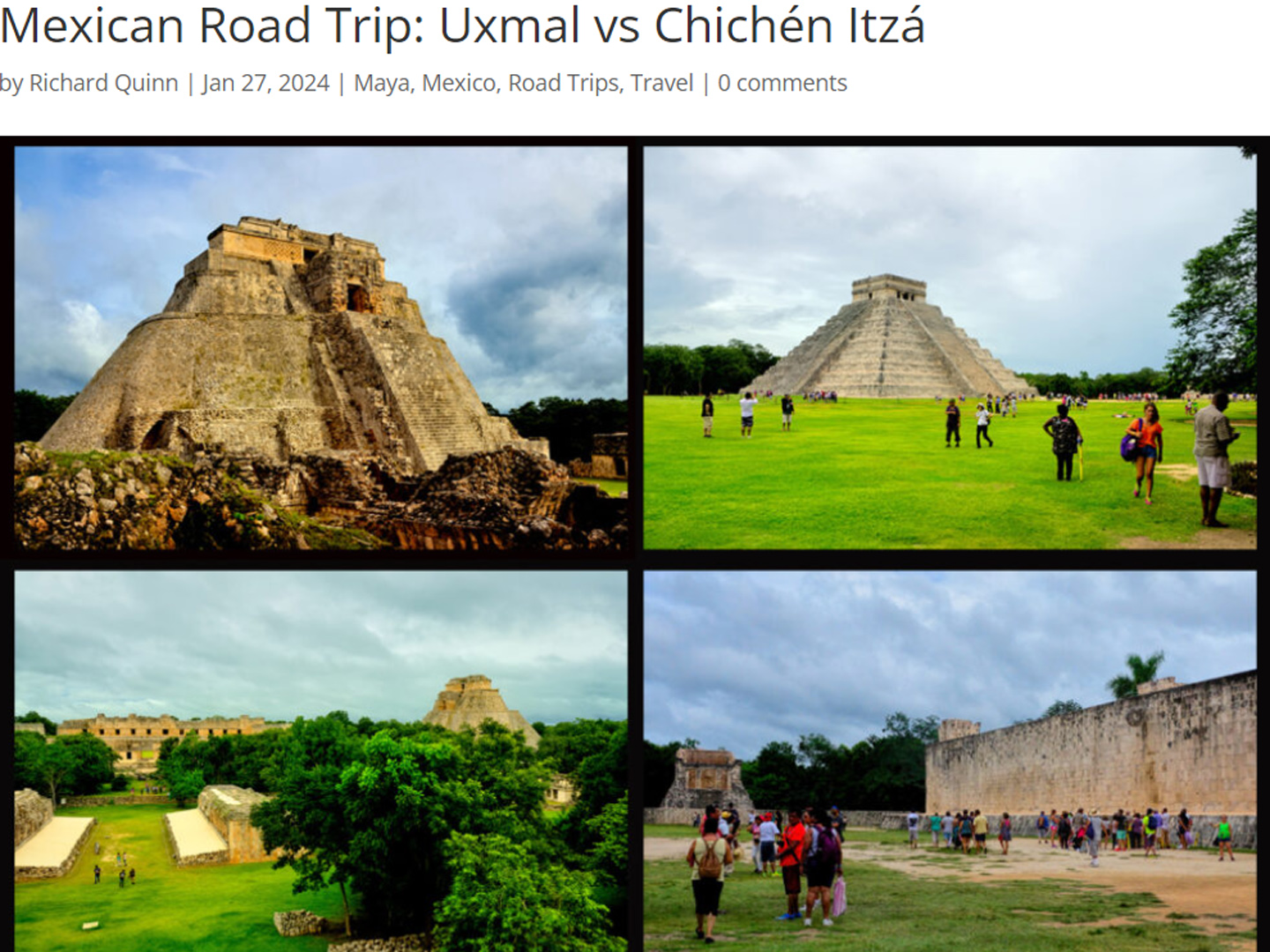

Uxmal, (pronounced, oosh-mahl), is the most aesthetically spectacular of all the Mayan cities. The beautiful setting, the quality of the architecture, the state of preservation, the wonderful plazas replete with flowering trees. This place has it all, and it’s not even isolated–it’s a mere hour south of Merida, a city of a million people, and the capital of the state of Yucatan. You’d think it would be crawling with tourists! But that is absolutely not the case, because the vast majority of the tourists in the Yucatan are concentrated in Cancun, on the opposite side of the peninsula. Chichen Itza and Tulum, both closer to Cancun, get as many as two million visitors in a year, while Uxmal gets less than 300,000. It has nothing to do with the quality of the site; it’s a matter of convenience. Uxmal is just a little bit too far from Margaritaville for an easy day trip.

Click any map or photo to expand the image

The location of Uxmal, relative to Chichen Itza and Cancun. Click for expanded view.

HISTORY OF UXMAL

The name Uxmal is thought to be derived from the Mayan oxmal, which means “thrice built,” a reference to the various stages of construction–often separated by centuries–that are common to Mayan cities. Investigations at the site have confirmed that the city was actually rebuilt five times, with distinctive layers representing each phase. New buildings and larger pyramids were built atop existing structures, a perfect way for each new dynasty of kings to put their stamp on the place, by making everything taller, broader, and ever more impressive.

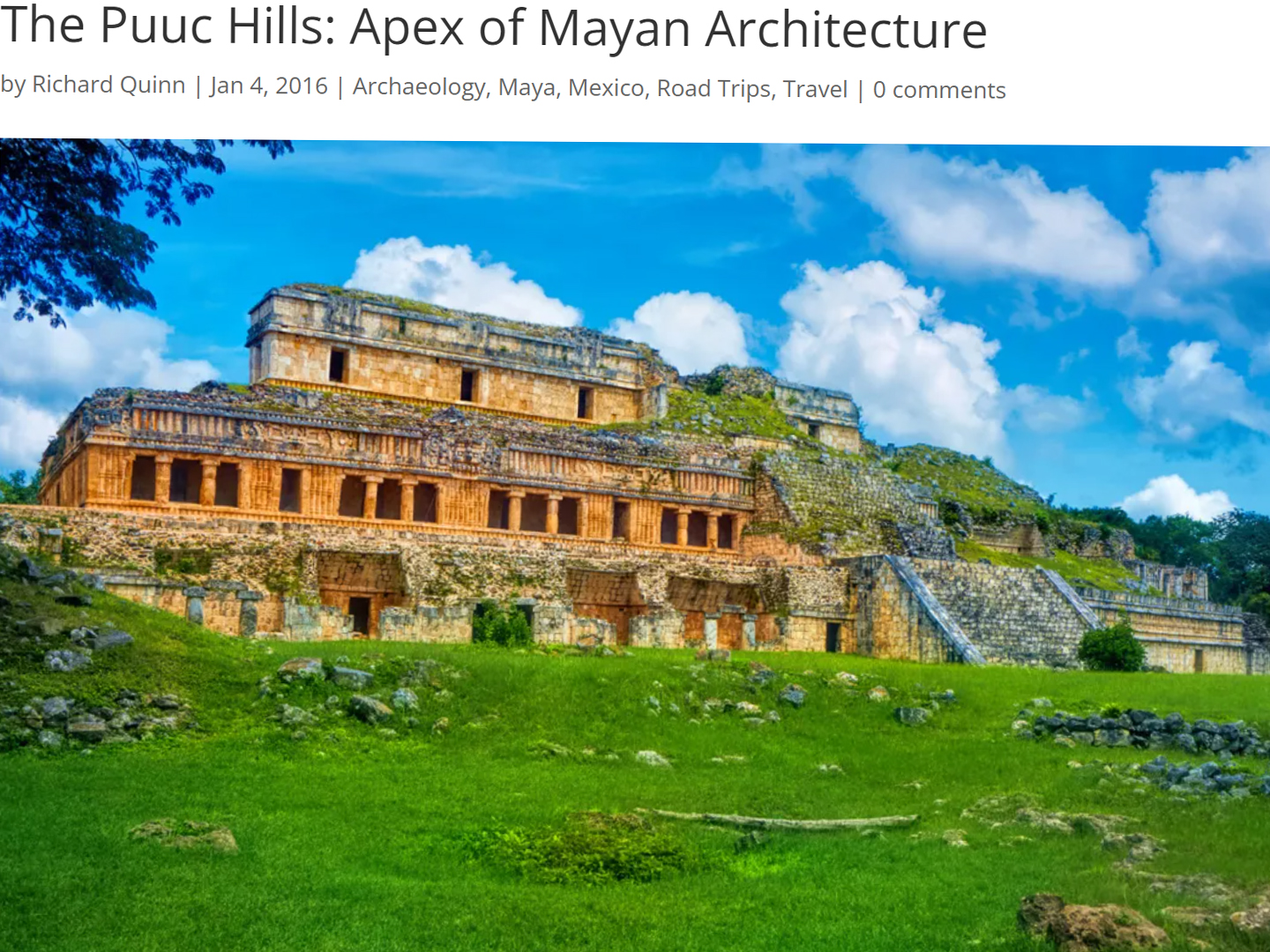

Pyramid of the Magician: five temples built one atop the other

The final version of Uxmal was one of the most important Mayan ceremonial centers of the late classic period, from 850 AD to about 925 AD. To put that in perspective, Uxmal was just starting to boom about the time Palenque began to fade. (See my previous post: Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas.) The two cities are separated by a significant distance, more than 500 km. While they may belong to the same tree (the sacred ceiba tree that supports the universe) they represent entirely different branches. Palenque is classic, old school, while Uxmal is thought to be at the pinnacle of post-classic Mayan art and architecture. Built in the Puuc style, which is characterized by buildings with smooth, lower walls built of precisely fitted blocks, devoid of decoration, topped by ornate cornices with elaborate friezes of carved stone, these structures display a perfection that is unmatched in the Mayan world. The facade on the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal is 300 meters long, the second longest frieze in all of ancient Central America. The complex as a whole is considered the best preserved of all Mayan ruins; in 1996, the Pre-Hispanic Town of Uxmal was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site.

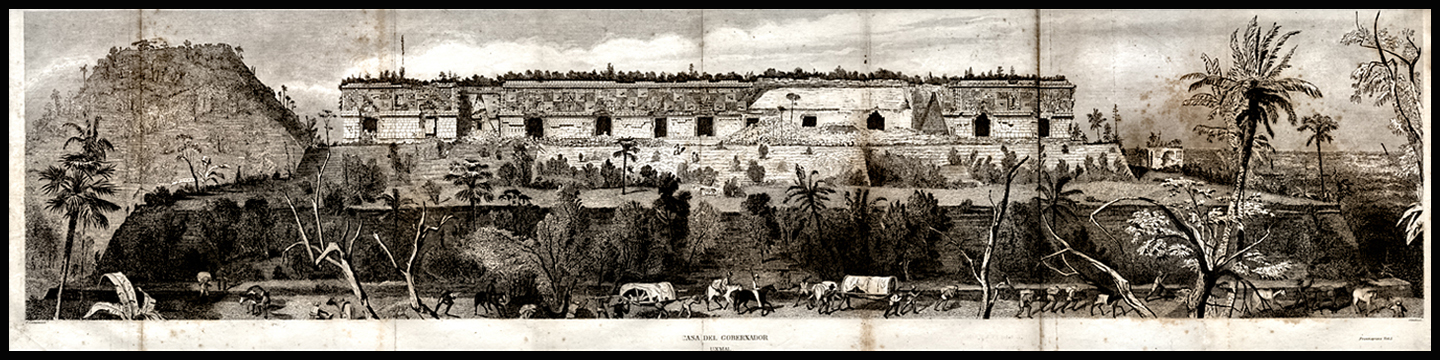

The Governor’s Palace, considered one of the greatest architectural achievements of all time

The Legend of the Dwarf

According to legend, the ruler of Uxmal entered a competition with a dwarf, a trial of strength and magic involving a series of challenges. The dwarf bested the king in the second challenge by building the big pyramid in a single night–aided by his mother, a witch with magical powers. The legend is the source of the common name for this structure: the Pyramid of the Magician, or the Pyramid of the Dwarf. In reality, the massive, 115 foot tall structure, which rises from a unique eliptical base, consists of five temples built one atop the other, with construction ongoing throughout most of the city’s history.

Uxmal’s earliest structures have been dated somewhere around the sixth century A.D. Construction and expansion continued sporadically for the next five hundred years as the city rose in stature, ultimately becoming the dominant political force in the Puuc region. The land was fertile and the rains were predictable, producing bountiful harvests that supported a population of as many as 25,000 people. All of their water came from rain, which they collected and stored in underground cisterns that were carefully managed to provide their needs during dry spells. An extended drought late in the 11th century exhausted all of those resources, leading to the abandonment of the city by its original inhabitants. When the rains returned, Toltec invaders from central Mexico moved in, and the new rulers of Uxmal joined forces with with the lords of Chichen Itza and Mayapan to form a powerful confederation that ruled the northern Yucatan through the 14th century, almost up to the time of the Spanish Conquest.

After the Conquest, Mexico became a colony of Spain, and the grandees divided the country into vast estates for their own enrichment. In 1700, that portion of the Yucatan that included the ruins of Uxmal was granted to the Peon family, for whom these “casas de piedra,” stone houses, were little more than a curiosity: buildings in ruins, overgrown by trees and shrubs so thick you could scarcely see what was beneath them.

In the 1830’s, French explorer and cartographer Jean Frederick Waldeck visited the area, and described the ruined city in a lavishly illustrated book about the Maya that was published in 1838. After that, the landowner ordered the ruins cleared, at least in part, so that any future visitors could get a better look at them.

STEPHENS AND CATHERWOOD

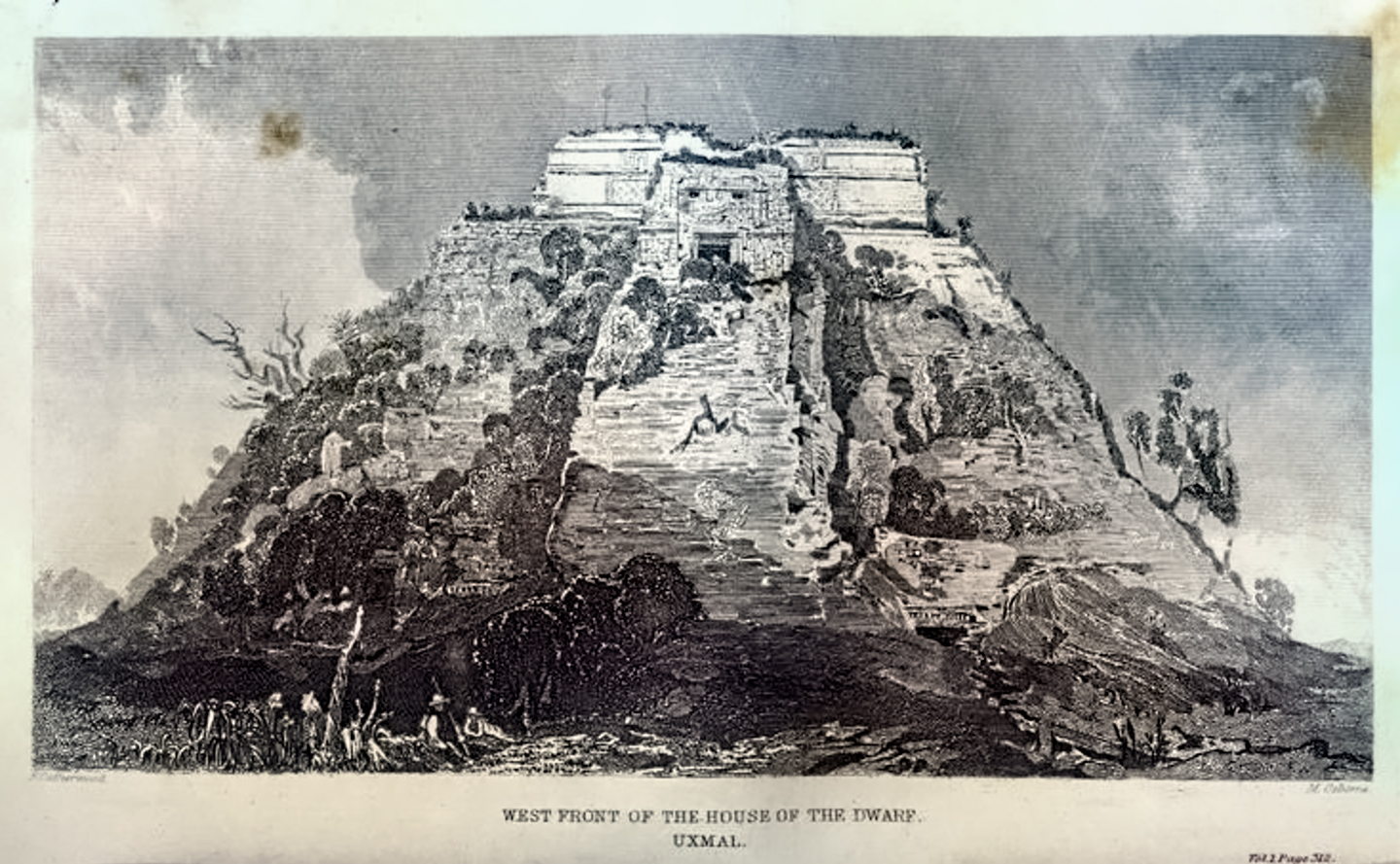

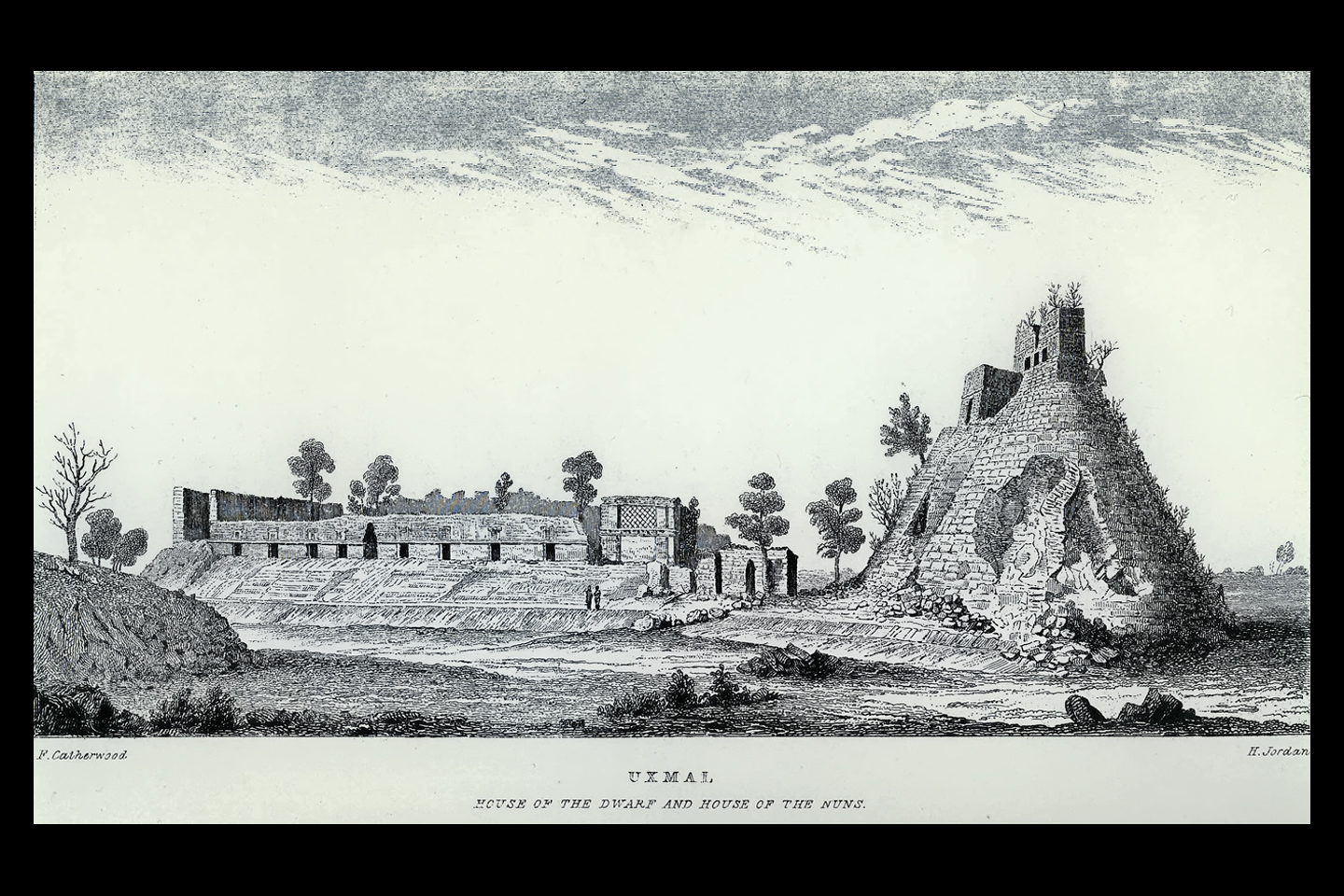

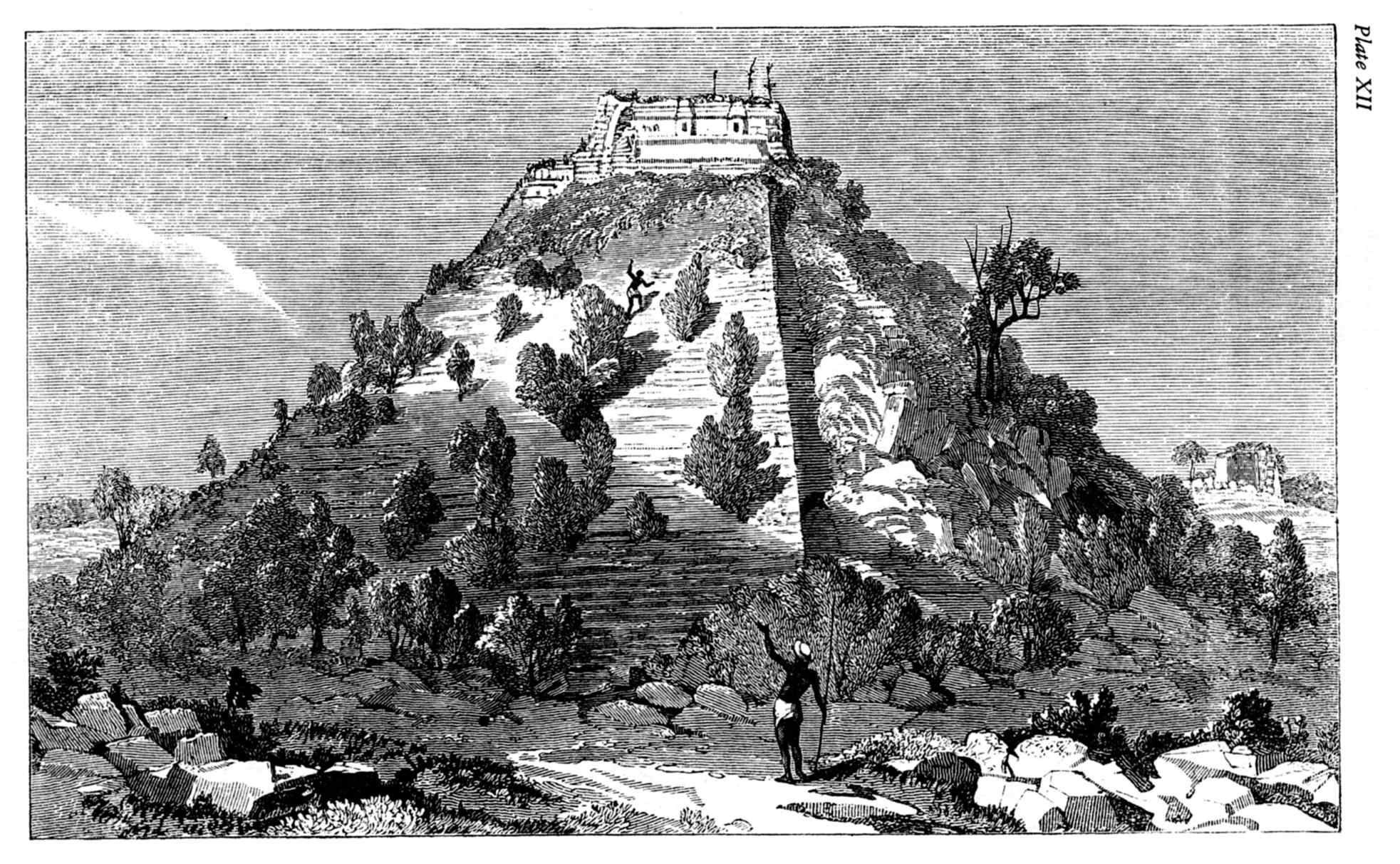

An early drawing of the Pyramid of the Dwarf, rendered by Frederick Catherwood, the artist who traveled with writer John Lloyd Stephens

In 1840, the American writer John Lloyd Stephens and his illustrator, Frederick Catherwood traveled through Central America and southern Mexico, documenting previously unreported Mayan cities. When they reached the Yucatan, they were personally invited to the Peon Hacienda by the owner, who described the ruins on his land in glowing terms. They’d learned to be skeptical of such claims, so they weren’t expecting all that much–until they saw the site for themselves. In his book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, first published in 1841, Stephens describes their first view of the ruins of Uxmal as follows:

“The place of which I am now speaking was beyond all doubt once a large, populous, and highly civilized city, and the reader can nowhere find one word of it on any page of history. Who built it, why was it located on that spot, away from water or any of those natural advantages which have determined the sites of cities whose histories are known, what led to its abandonment and destruction, no man can tell. The only name by which it is known is that of the Hacienda on which it stands.”

Rendering of the Uxmal ruins by Federick Catherwood, 1840, from the book “Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan”

Frederick Catherwood was quite taken by the extraordinary ruins, and over the course of two extended visits, he made countless drawings of the site. It’s said that his renderings were so precise, they could have been used as blueprints to reconstruct the entire city from scratch. Most of those drawings were burned in a tragic fire, but those that survived are enormously important. It was Catherwoods’ remarkable illustrations that turned Stephens’ two-volume travel book into a widely acclaimed best seller. By the middle of the 19th century, the ancient Maya, and the city of Uxmal, previously unheard of, were suddenly all the rage.

The back side of the Pyramid of the Magician, a Catherwood rendering done in 1840. There’s no doubt that it looked just as you see it in his drawing: a pyramid with an impossibly steep staircase, all the way to the top, overgrown by trees and shrubs, which the landowners had just begun to clear.

The back side of the pyramid as it appears today, cleared and largely restored. Set on an eliptical base, the 115 foot tall structure is among the most famous buildings in the Mayan World. The steps that you see rise at an angle of 60 degrees. Climbing on any part of the pyramid is prohibited, to avoid damage to the centuries-old structure.

Located just off the main road between Merida and Campeche, Uxmal has always been easily accessible, and it has attracted visitors from every corner of the globe for most of the last 200 years. In all that time, there have been surprisingly few serious studies of the site, so while Uxmal is one of the Mayan cities that is best known to the outside world, at least, by reputation, the science of archaeology has barely scratched the surface. Sylvanus Morley created the first map of Uxmal in 1909, and conducted preliminary studies at that time. In 1927, the Mexican government began a program of repair and restoration, to stabilize the most important buildings. These efforts have been ongoing, and quite successful. The erstwhile Count de Waldeck would scarcely recognize the place as the same overgrown ruin he first encountered in the 1830’s.

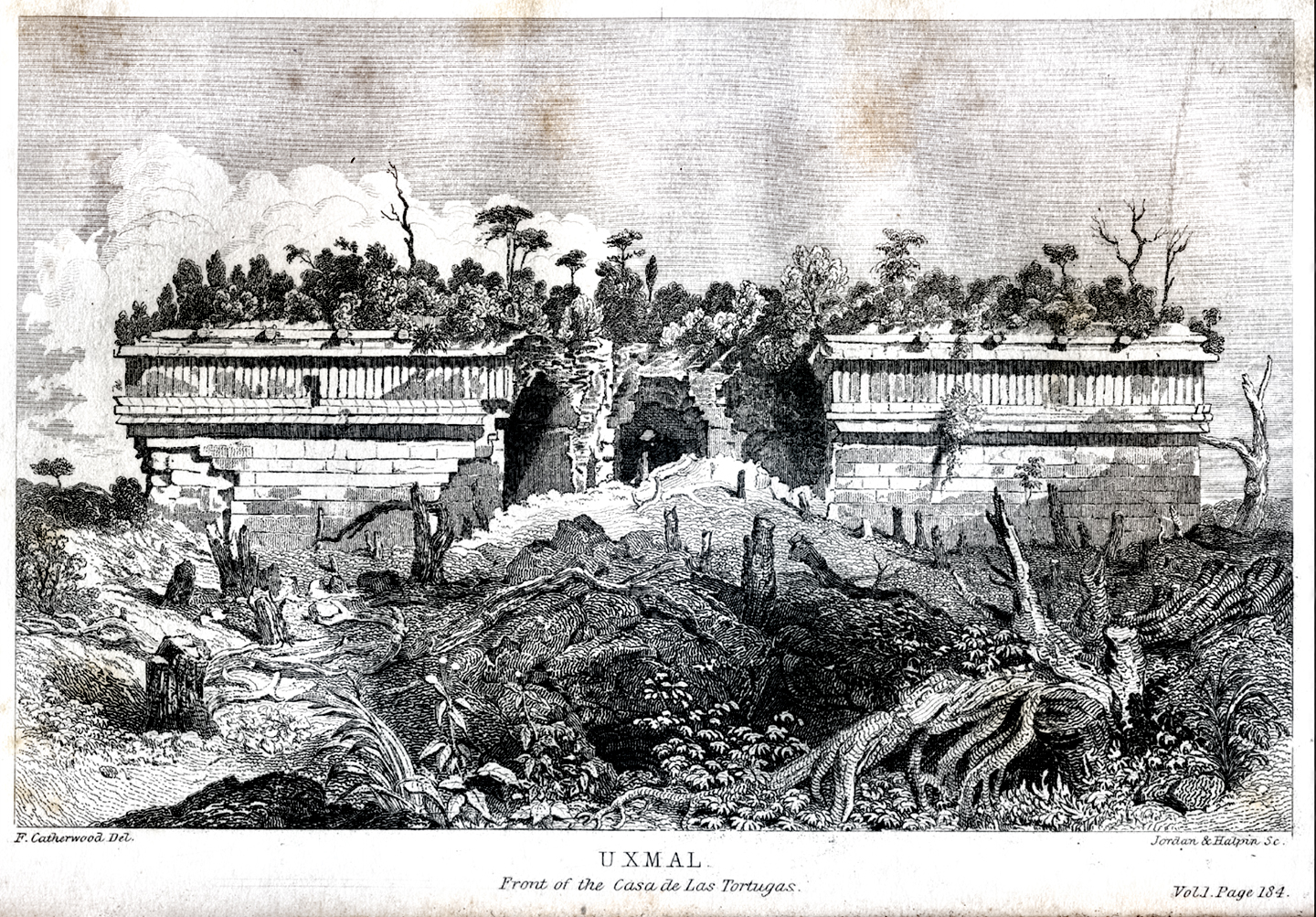

House of the Turtles, a Catherwood rendering from 1840. Prior to early restoration efforts, the forest was actively devouring these ruins, and had almost finished the task.

VISITING UXMAL

From the parking lot, the entrance to Uxmal looks like the entrance to a shopping mall, or a movie theater. In reality, this unassuming doorway is a portal into the world of the Ancient Maya, a world that transcends time.

On my own trip to Mexico back in 2015, we drove to Uxmal from Merida early in the morning. We had a reservation at a great hotel called the Uxmal Resort Maya that was just minutes away from the ruins; relatively new, quite clean, and reasonably priced. They actually let us check in early, and once that was done, we headed straight over to the archeological park, arriving just as they opened the gates at 8:00.

A tip for photographers: arriving early is critical. 90% of the visitors come on tour buses that start rolling in an hour or so after opening. That first hour, before the buses arrive, is your best, often your only opportunity to take your pictures without a crowd of your fellow tourists in the frame.

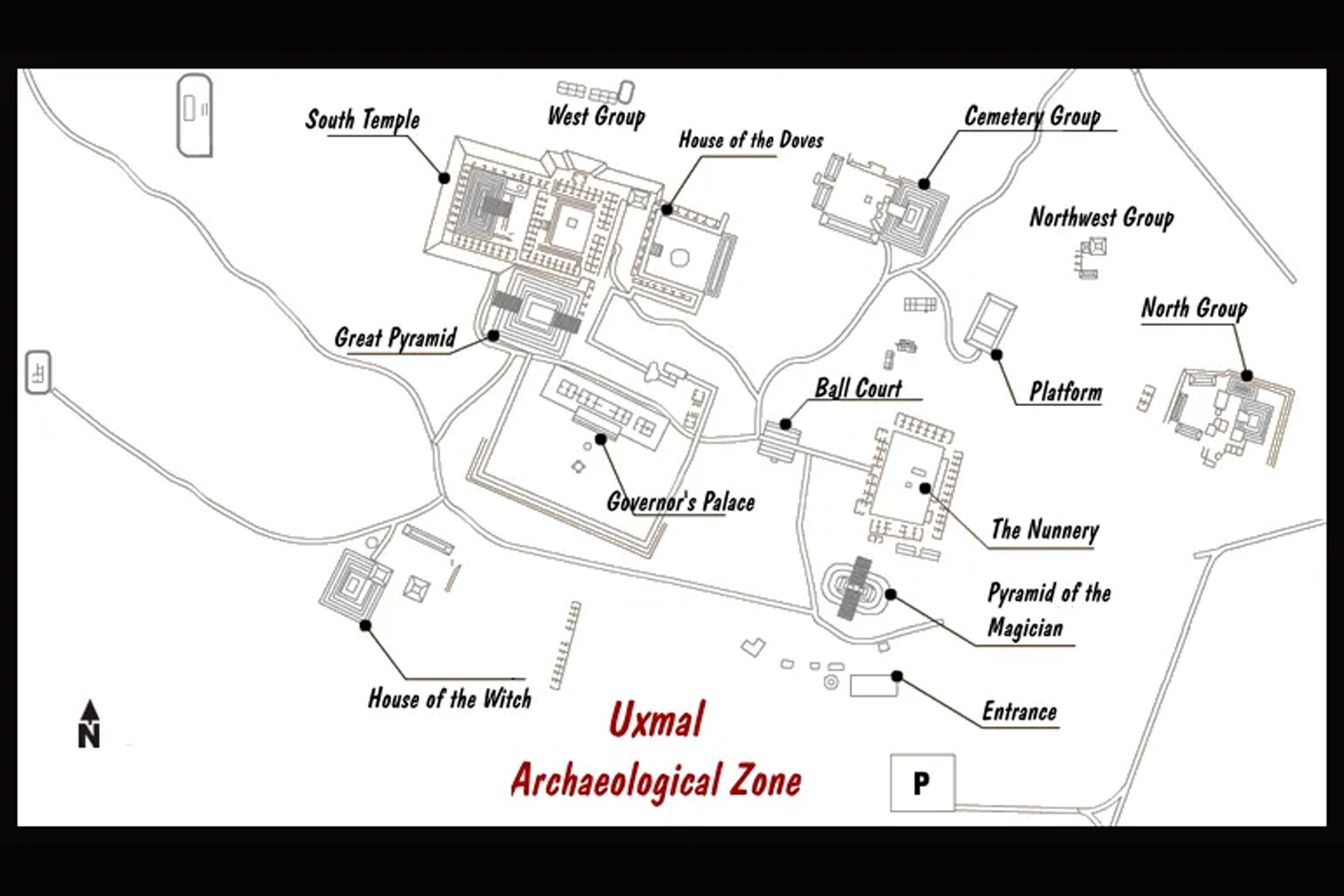

The Uxmal Archeaological Park as it exists today. It is estimated that there are at least 500 buildings associated with this magnificent ceremonial complex. The vast majority of these are still buried by the surrounding forest. (Click map to expand)

Whether you’re coming from Merida, 50 miles to the north, or from Campeche, 100 miles to the south, you’ll arrive at Uxmal off MX 261. When driving in Mexico, it’s recommended that you stay on the Cuotas, the toll roads, which are better maintained and considered safer for travelers. MX 261 is NOT a Cuota, but in this case, you have no other choice. State highways are slower than the toll roads because there is more traffic, and they travel through the middle of all the tiny towns. More picturesque, but most definitely more dangerous, with livestock and numerous other hazards in the middle of the highway, and brutal concrete speed bumps (topes) serving as passive traffic enforcement. On the back roads of Mexico, every journey is an adventure!

For more tips on driving in Mexico, see my post: Mexican Road Trip

Easy, reasonably secure parking, right by the entrance, for a nominal charge

At Uxmal, there’s a parking lot with plenty of spaces. The charge was just 22 Pesos for the whole day, and unlike Palenque, there were no hustlers offering to watch, or wash, my Jeep. The entry fee to the ruins was steep, compared to Palenque: 254 Pesos, about 16 bucks each, but it turned out to be well worth it. There were no more than two dozen other visitors at the time we were there, so it was almost like having the place to ourselves. This was mid-October, still the rainy season, so still the off-season for tourist destinations, very much to our advantage.

(Note: prices quoted were correct in 2015; they’ve all gone up a bit.)

Pay your fees at the entrance, and if you’d like to join a tour, there are options available right there at the park. If you don’t feel you need a guide, follow the paved walkway, down the rabbit hole, and into the fabled city of Uxmal, wonderland of the ancient Maya.

EXPLORING THE RUINS

The first thing you’ll see is the back side of the Pyramid of the Magician, rather plain from this angle, but at 115 feet in height, it’s imposing nonetheless. When you walk around to the front, that’s where the real power of the structure reveals itself. Whatever name you call it by, that thing is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen anywhere. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal–let’s just say it gave me the creeps, all the down to the marrow. They won’t let you climb it anymore, because the steps are deteriorating, but even if it was allowed, I don’t think I would have tried, out of respect for all those lost, tortured souls who died there. A pyramid such as this, built entirely by manual labor, is an incomprehensibly expensive undertaking, and the cost is far greater than the value of the materials, or the man hours required. The true cost of a pyramid such as this has to be measured in human lives, all the lives that are given, taken, or simply used up, before, during, and after the interminable construction of the beastly thing.

Several views of the west side of the Pyramid of the Magician, including a closeup of the doorway to Temple IV, which represents the open mouth of Chac, the rain god, the most important deity in the Mayan pantheon. During ceremonies, Mayan priests in their elaborate feathered robes would emerge from that doorway, a grand spectacle meant to intimidate their audience.

Plaza on the west side of the Pyramid of the Magician, facing the Quadrangle of the Birds

There is a spacious plaza in front of the pyramid on the west side, the space where crowds once gathered to watch the brutal spectacles that played out at the top of those steps. Captives were taken in war and utilized as slaves, with a certain number reserved for the priests to use as grist for their mill of human sacrifice. Victims were tied down, and their still-beating hearts were cut from their chests as an offering to bloodhirsty gods.

QUADRANGLE OF THE BIRDS

On the opposite side of the plaza in front of the Pyramid of the Magician you’ll find the Quadrangle of the Birds, so called for the carvings of birds that adorn the upper walls of the buildings. Birds are a common element in the decorative friezes surrounding these Puuc style buildings. Birds were important to the Maya as a source of food, as well as a source of valuable feathers, but their real significance was religious. Birds were vessels of the gods, and played an important part in a variety of religious rites.

NUNNERY QUADRANGLE

Just beyond the Quadrangle of the Birds is another group of buildings surrounding a courtyard. The original purpose of these structures is unknown, but they have long been referred to as the Nunnery, because the early Spanish explorers thought that the small rooms in the buildings resembled Nun’s cells in a convent. The buildings are classic examples of the Puuc architectural style, featuring smooth, lower walls topped by ornate cornices. The carved stones in the walls form a precisely fitted veneer, set into a structural core of built up concrete. This building technique was an innovation developed by the Mayan stone masons to reduce the thickness of the outer walls, allowing much more spacious interiors.

Perfectly geometrical stone lattice surrounding three Chac masks, stacked one atop the other

Well-executed carving of a plump bird with stubby wings, one of many representations of birds at Uxmal

A snake, slithering his way through the complex design, the rattles at the end of his tail clearly depicted

The stone friezes surrounding the tops of these buildings are comprised of complex geometric designs that incorporate elements of the Mayan religion. Chac, the big-nosed rain god is an important theme that is frequently repeated, with Chac masks stacked one atop another at every corner, and above most doorways. Birds are another common element, and there is even a rattlesnake, with its rattles plainly visible in carved relief.

Designs were created by mass producing the components and assembling them in place like pieces of a puzzle. In some areas, cut stone still litters the ground.

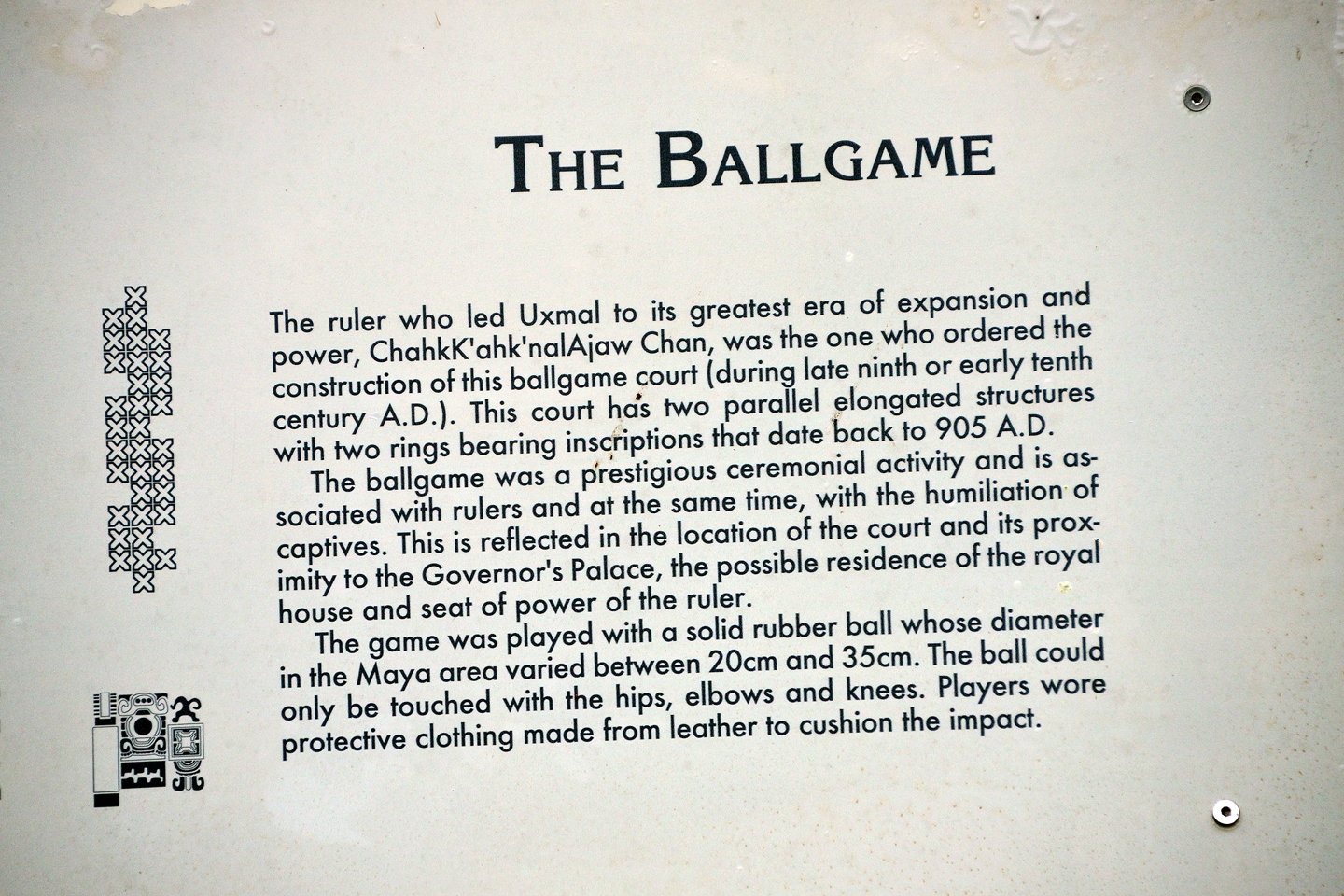

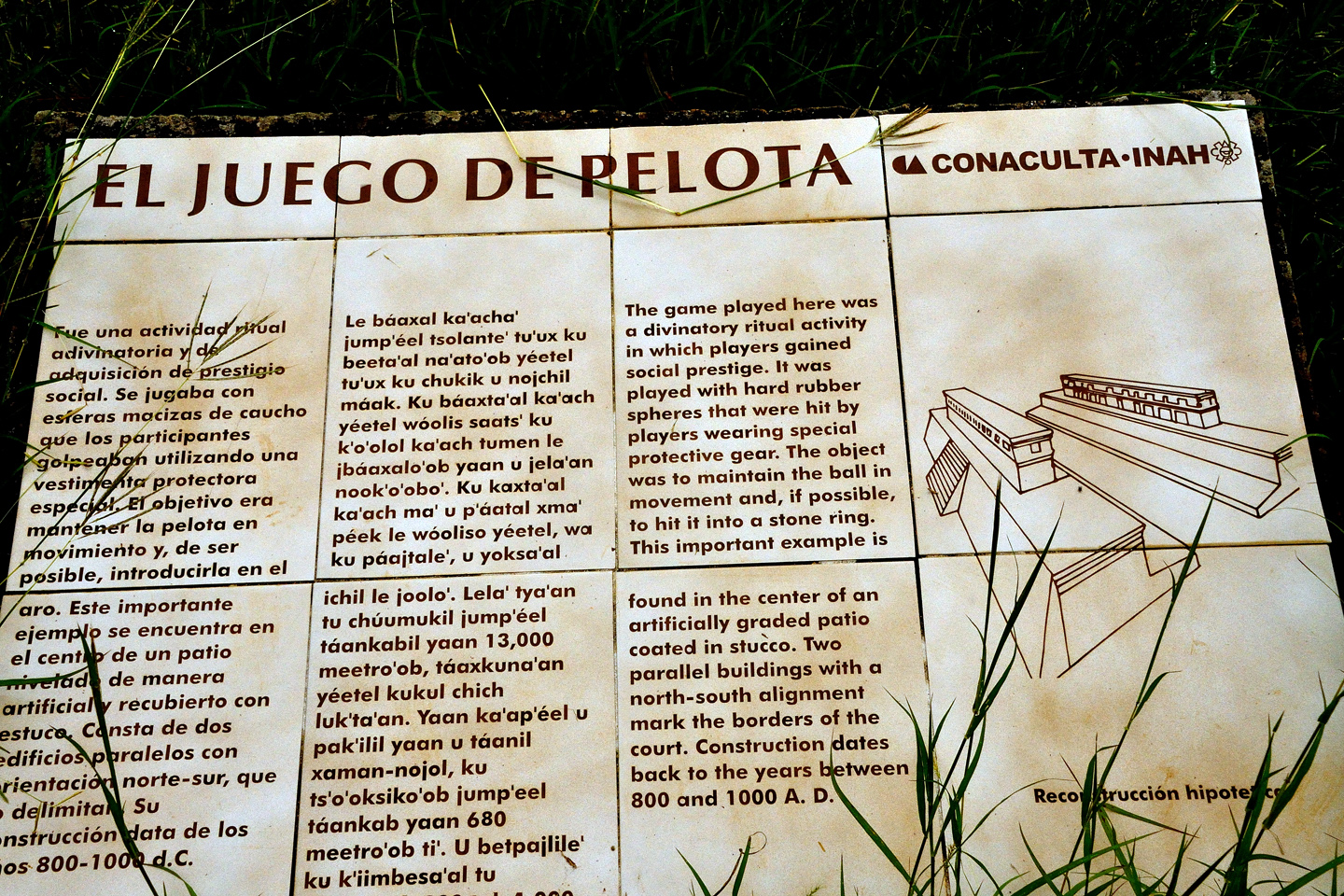

THE BALL COURT

South of the Nunnery Quadrangle there is a ball court that was used in a ceremonial game of skill. Contestants had to keep a hard rubber ball in play, not letting it touch the ground, using only their hips, elbows and knees, never their hands or feet. Thick leather armor was required to protect them from the ball, which was 30 cm in diameter and quite heavy. They’d score points by knocking the ball through a stone ring attached to the sloping side of the court, which was finished with smooth stucco. The game was deadly serious: the losing team was usually sacrificed to the gods.

Several views of the Ball Court. The original stone goal rings were deteriorating from exposure to the elements, so they were removed, and replaced with the reproductions seen in these photographs.

THE PALACE OF THE GOVERNOR

The building known as the Palace of the Governor is one of Uxmal’s most well known features. Like everything else in the city, it was built directly above older structures, including passageways and staircases that have been sealed off from above. The Palace actually consists of three buildings, all level with one another, joined by walkways featuring corbelled arches, and the entire five acre complex is elevated atop a triple terrace fifty feet high. There are 24 interior rooms that may have been used for administrative or religious functions, or perhaps as a royal residence. The building is massive, 320 feet long, 40 feet wide, and 26 feet high. The mosaic frieze surrounding the upper section is 300 meters long, and was assembled from twenty thousand individually carved elements. When we think of a mosaic, we imagine a picture or a decoration made of small pieces of stone or glass. There is nothing about this Mayan mosaic that could be considered “small”. Many of the thousands of “individual components” are as much as a yard long, carved from solid stone weighing hundreds of pounds.

There is perfection here, architectural perfection, to be sure, in the purity of the design, but to bring such concepts to fruition required much more than intellect. The palace is a marvel of engineering and a consummate display of artistry, executed on a grand scale, and built in perfect alignment with important celestial events. There’s nothing to match it in the Mayan world–or in any other world.

JAGUAR THRONE

In the plaza below the Palace of the Governor is a carved stone seat, featuring the head of a jaguar on each side, facing in opposite directions. It is widely believed that Uxmal’s rulers used the seat as a throne during ceremonies. That’s what you might call a “best guess,” since there’s no way to prove it, one way or the other. The jaguar was an important deity for the Maya, and for most other cultures in the tropical latitudes of the Americas. He was by far the most powerful animal in the forest, so his spirit was an important ally.

THE PILLORY STONE

Near the Jaguar Throne, in the same plaza, there is another carved stone, mounted at an angle on a square base. As it appears today, devoid of any ornamentation, it’s easy to see why the Spaniards likened it to a pillory, a support for tying down prisoners undergoing a flogging. Try to imagine the stone as it may have appeared back in the day, stuccoed, painted, and adorned with glyphs. It’s just as easy to see it as the Ya’axche Cab, the base of the sacred tree that supports the Mayan universe. Personally, I like that much better.

Extensive work has been done to stabilize and restore the city of Uxmal, but the ruins are so well preserved, relatively little actual reconstruction was required. Uxmal is by far the best example of a Mayan city that still appears much as it did when it was built, with at least one important difference. In their heyday, the buildings, including the decorative frieze, would have been painted, with a lot of red, blue, yellow, and black. We can only imagine how that would have looked.

THE GREAT PYRAMID

Beyond the Governor’s Palace is a truncated step pyramid, 90 feet high and more than 300 feet wide, with a small temple at the top. Known as the Great Pyramid, this one is only partially excavated; if you walk around to the back side of the sructure, you’ll get an idea of how these ruins looked before they were cleared. The steps on the front side, on the other hand, are in such good condition that visitors are still allowed to climb them.

There’s a technique to climbing a Mayan pyramid: the steps are very narrow, and the risers are quite tall, which makes the pitch of the stairs dangerously steep. For safety’s sake, and as a purely practical consideration, it’s best to stay parallel to the stairs, to keep your feet sideways on the steps, and to move diagonally upward as you climb. Your feet get a better purchase, and you’re less likely to slip. You don’t want to slip on one of those staircases. A fall down those steep stone steps could be a disaster.

HOUSE OF THE PIGEONS

Just west of the Great Pyramid is another well known structure called the House of the Pigeons. There is a crumbling wall with dozens of small openings, bringing to mind a dovecote for housing birds. No doubt there were more than a few birds nesting in those spaces when the ruins were cleared, but that’s not likely to have been their original purpose. Part of the south temple complex, these are among the oldest structures at Uxmal, pre-dating the Palace of the Governor by several hundred years.

Every crack in every wall contains enough windblown, time-worn soil to provide nourishment for a seedling. Before you know it, you have trees sprouting from the tops of walls, and wild house plants growing sideways in the most unlikely places.

Maintenance of the grounds at all the Mayan archeological parks is an ongoing battle against a forest that is constantly encroaching. Major sites like Uxmal, Chichen Itza, and Palenque stay in pretty good shape, as they have more funding and more staff, but as you can see in these photos, the vegetation is relentless.

Some of the encroaching plant life actually improves the ambience. At these tropical latitudes, most flowering trees and shrubs produce beautiful blooms all year around, adding a welcome splash of color to the scene (below).

Click any photo to stop the slides from advancing, and expand the images to full screen.

Uxmal is a place that should be savored, so if you visit the ruins, don’t settle for the two hour tour. It took the Maya 500 years to build the place, so the least you can do is take a full day to appreciate their efforts. Of all the Mayan cities I’ve visited myself, Uxmal is my favorite, without any doubt. We can only imagine what it would have been like when it was still in use, with all the sights, sounds, and smells of a living city teeming with people, with the kings and nobles in their palaces, and the priests in their temples. What a different world that was, and not so very long ago.

Click any photo to expand the image

Click the link to launch a Full Screen slide show featuring an assortment of my favorite photos from Uxmal. These super-sized slides are best viewed on a full sized monitor or a tablet. They’re not properly configured for a Mobile browser.

Note: This is a revised and expanded version of a previous post on this website that was titled: Uxmal: The Most Perfectly Preserved Mayan City

Unless otherwise noted, all of these photographs are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

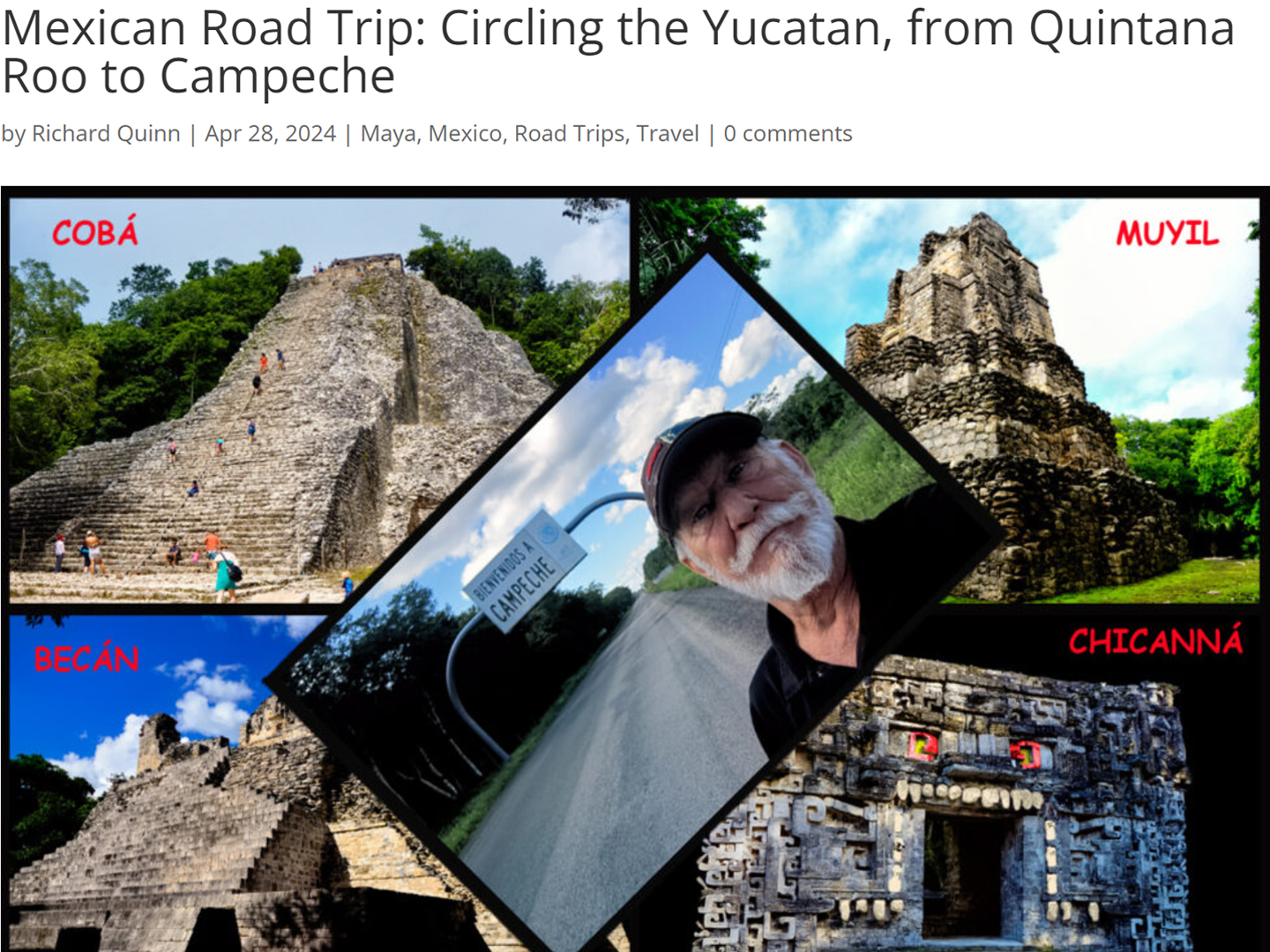

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn’t huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

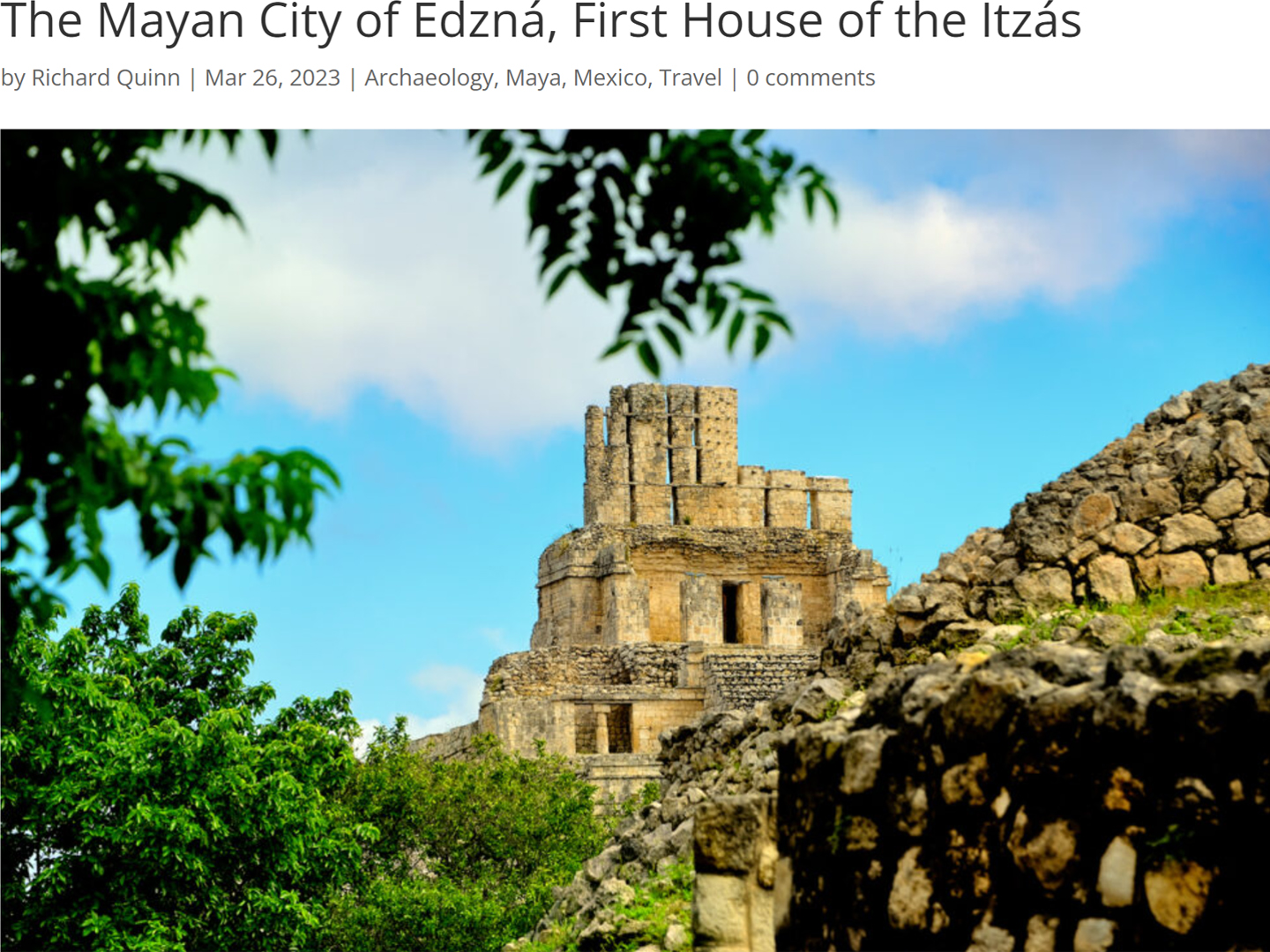

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

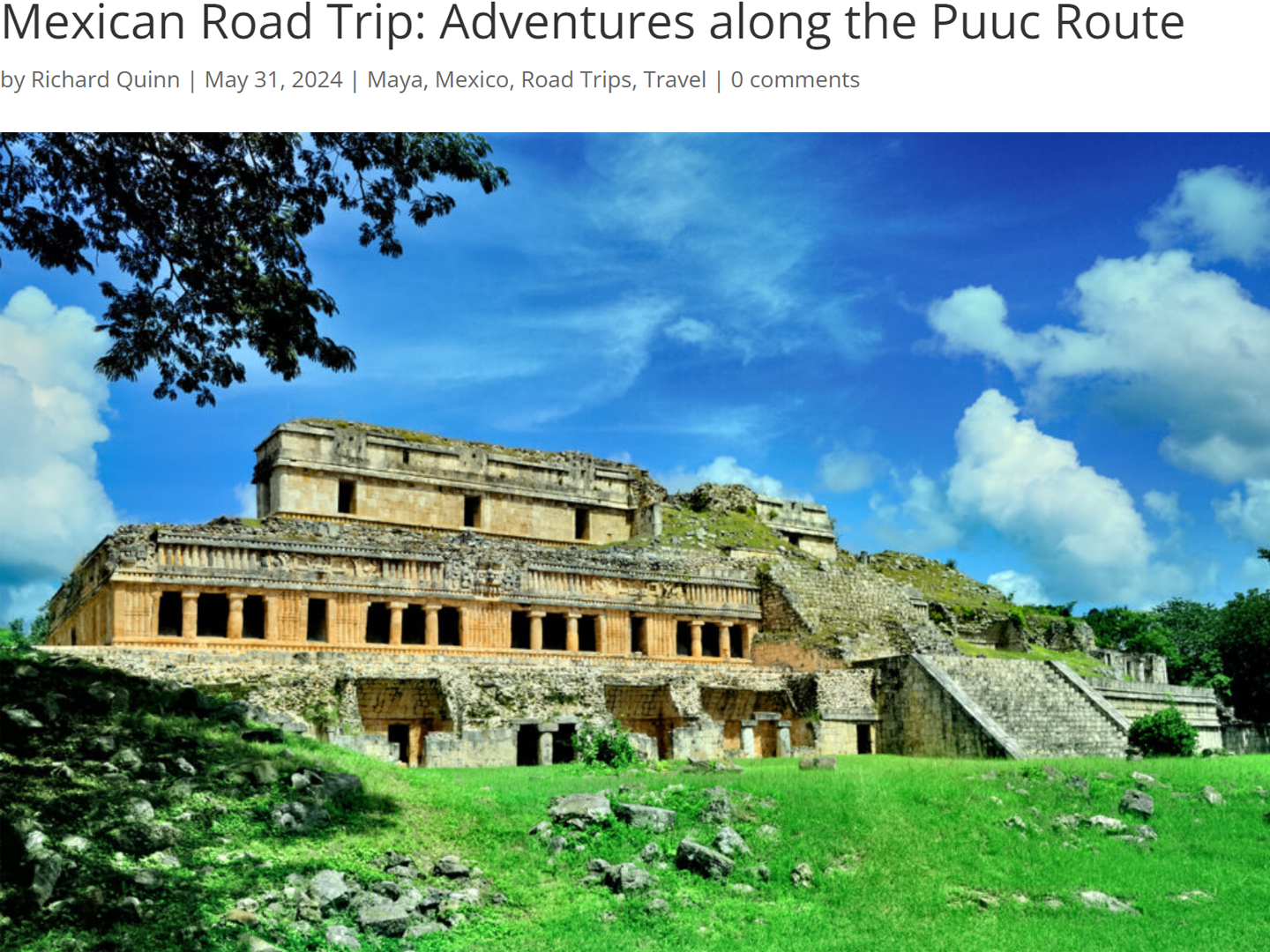

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

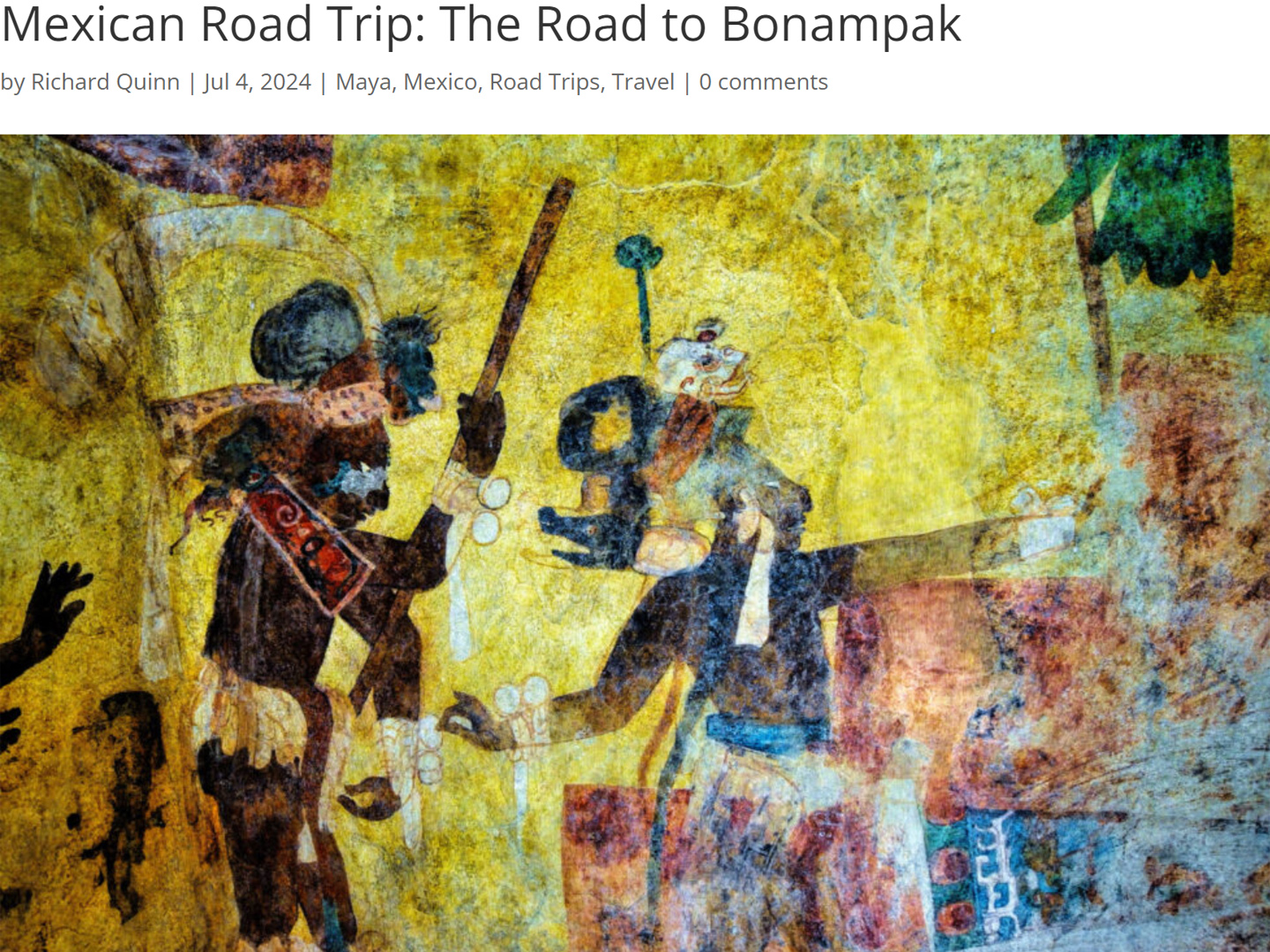

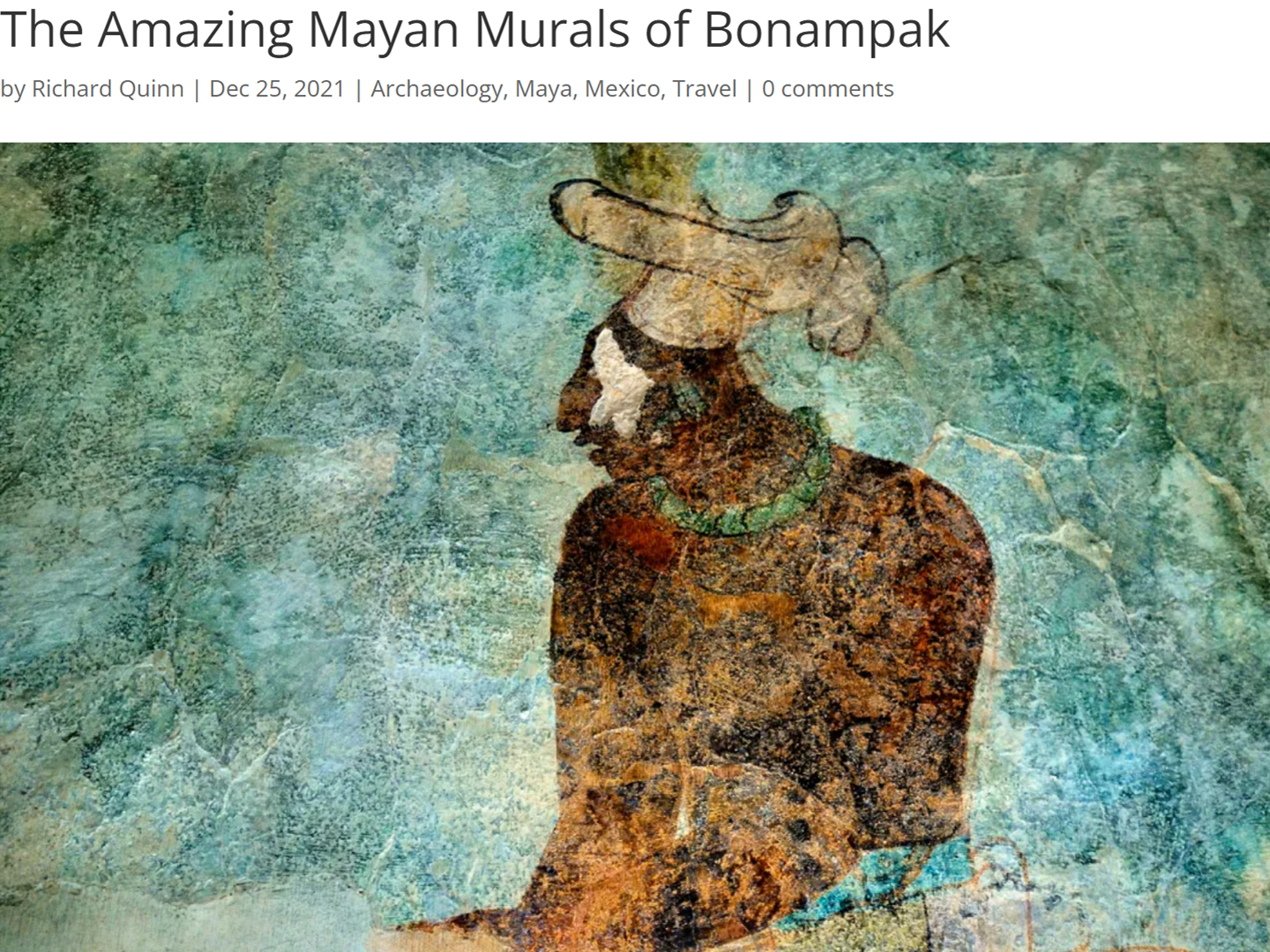

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we’re left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

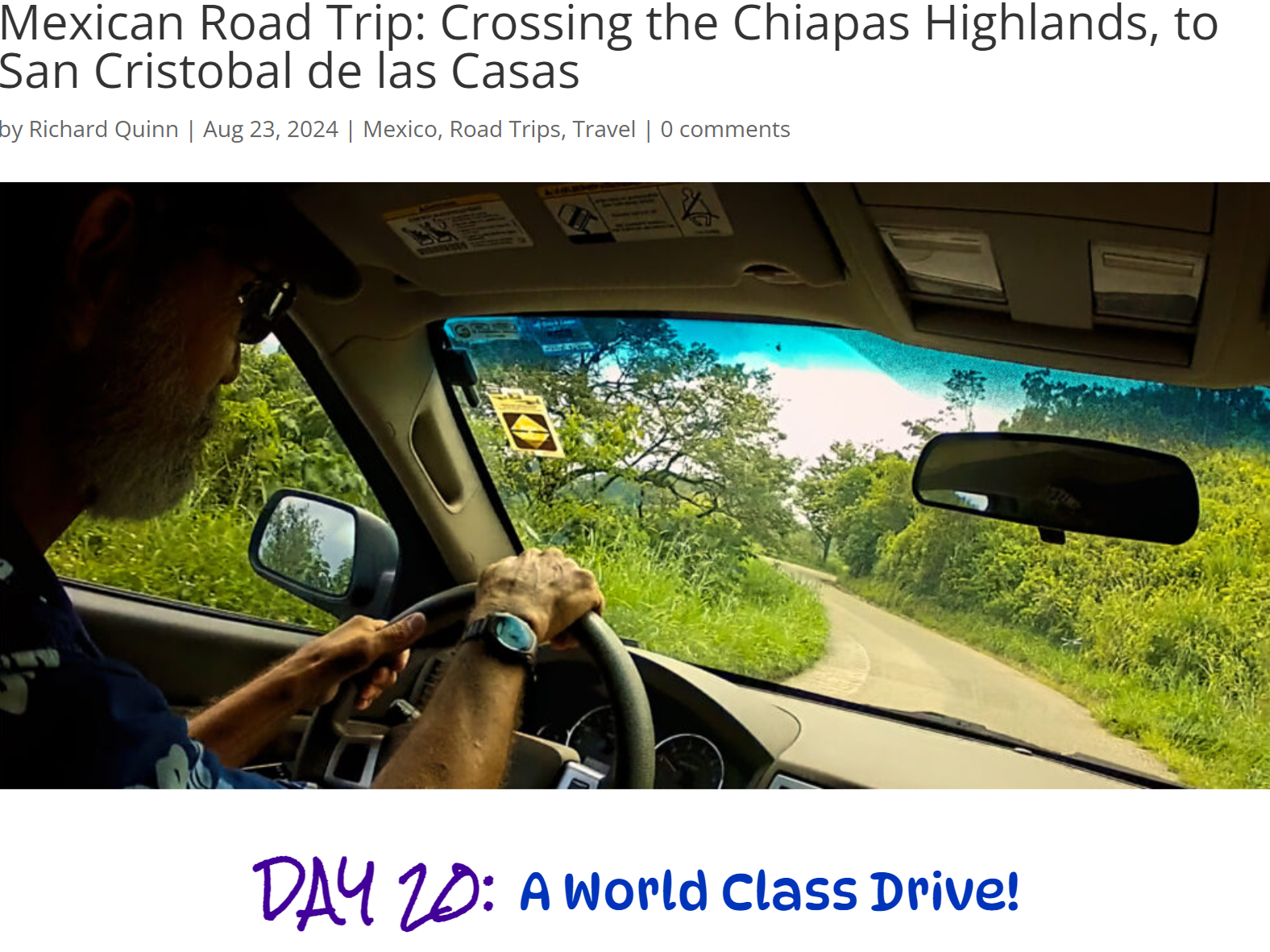

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it’s 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in March, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

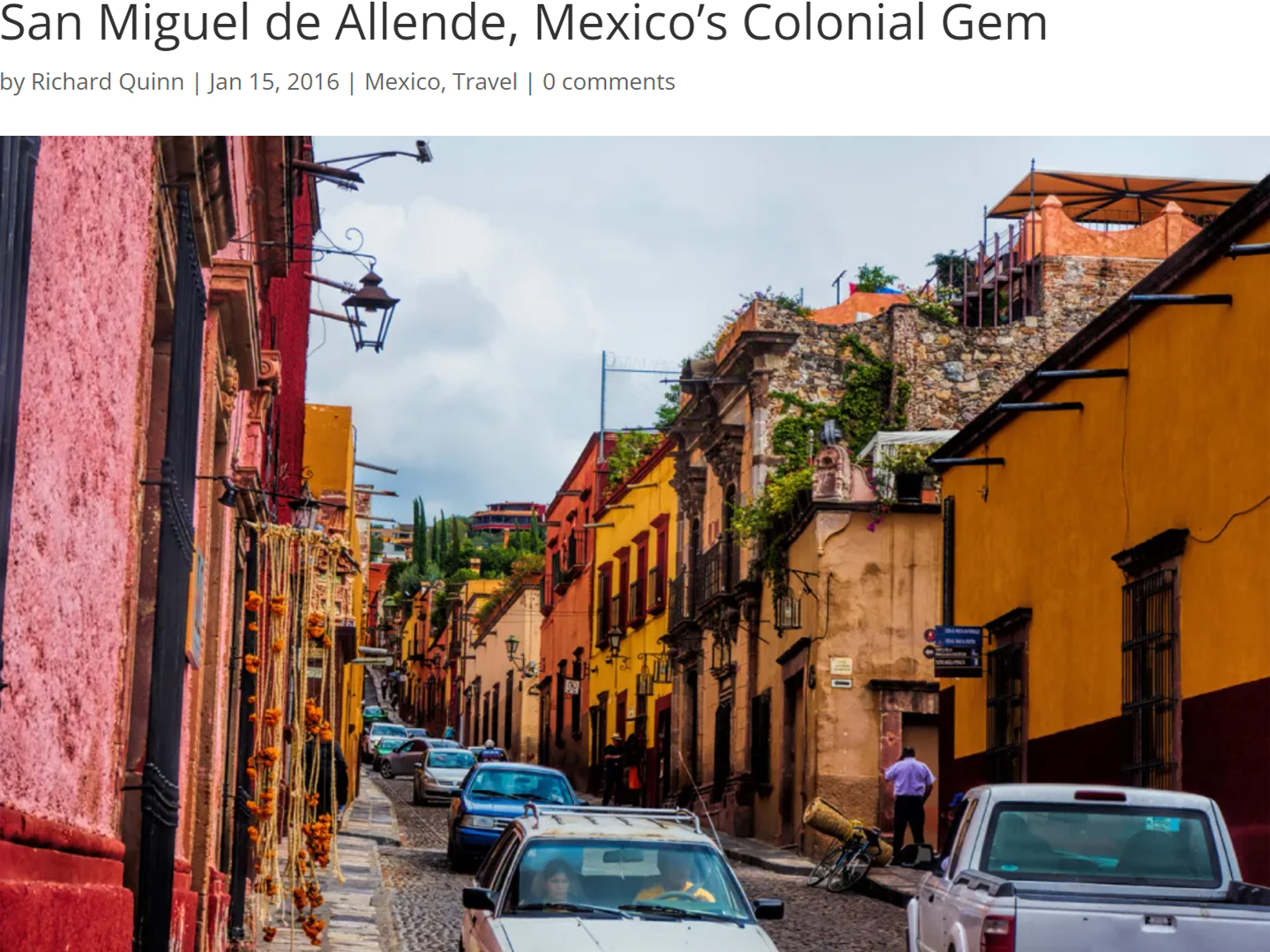

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico’s Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they’ve adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It’s a wonderful, colorful parade that’s all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

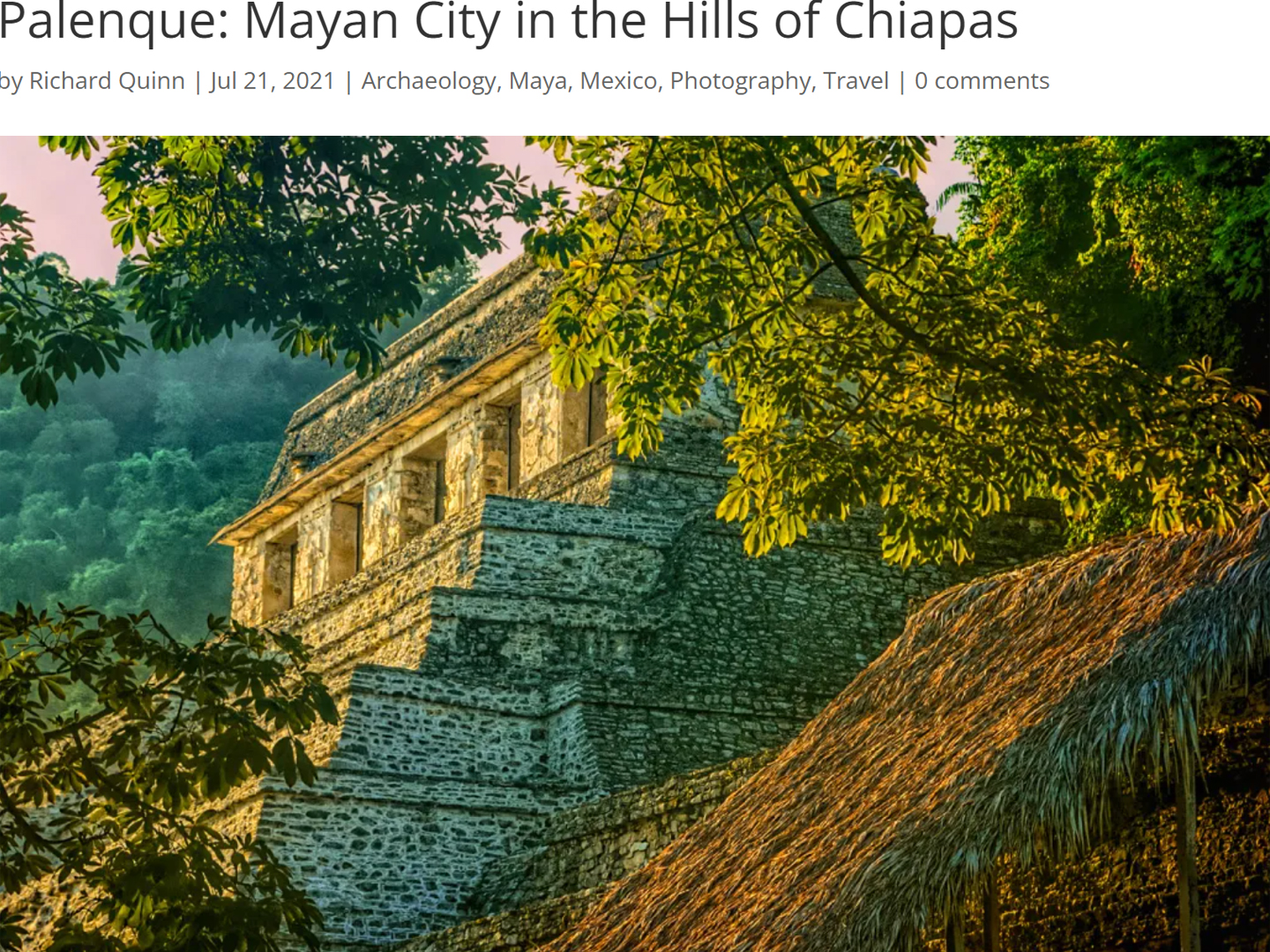

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

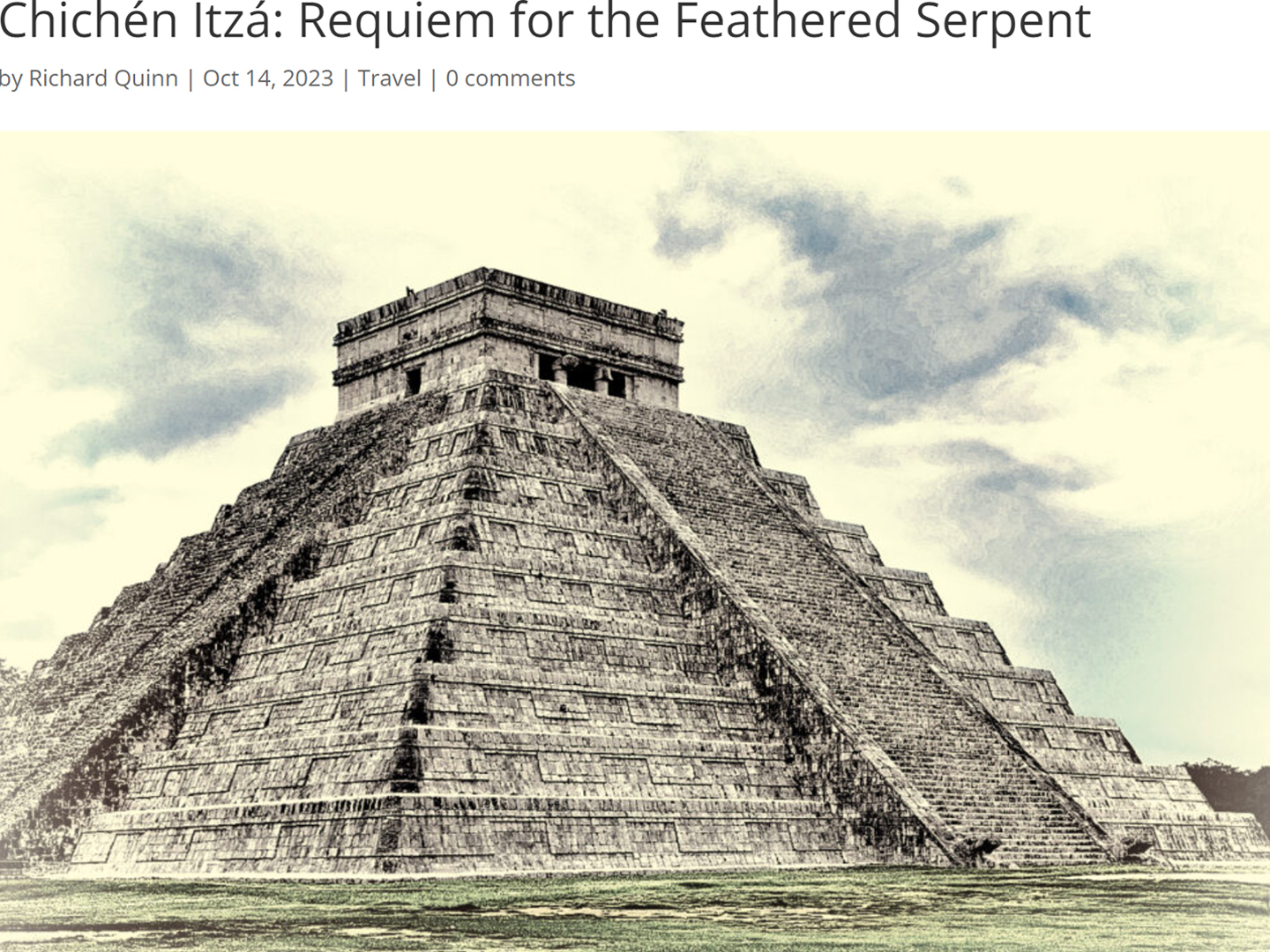

Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

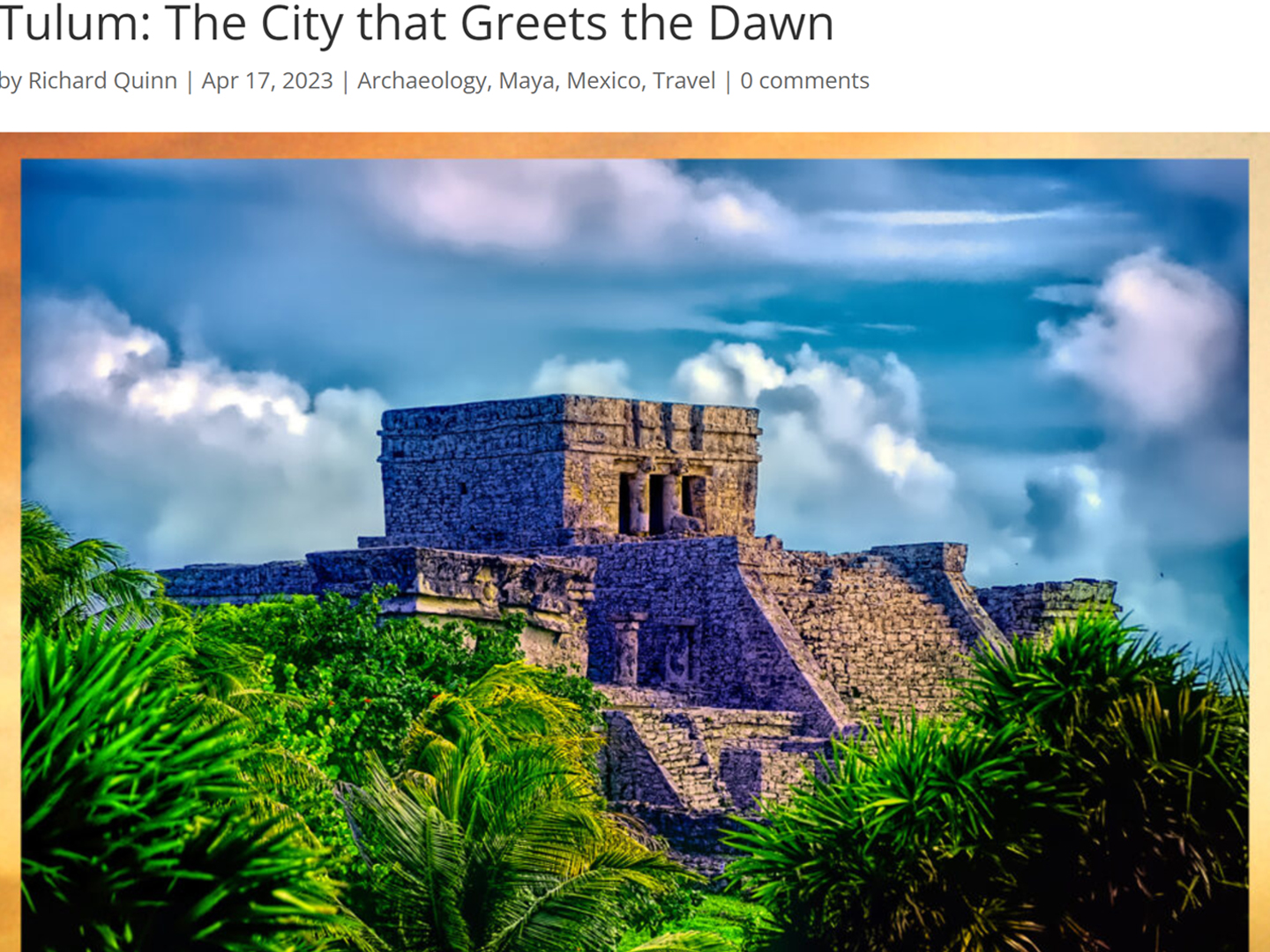

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

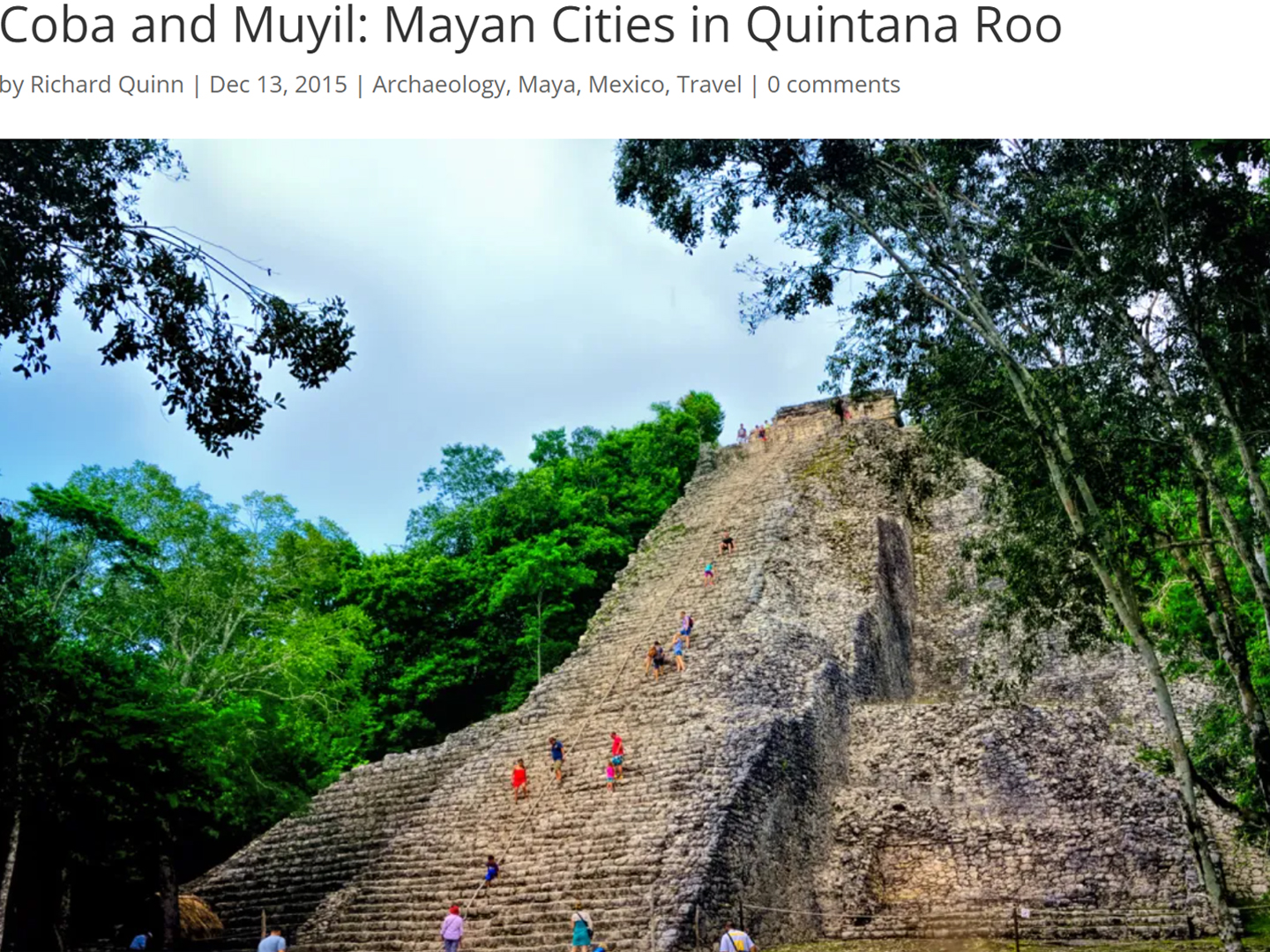

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

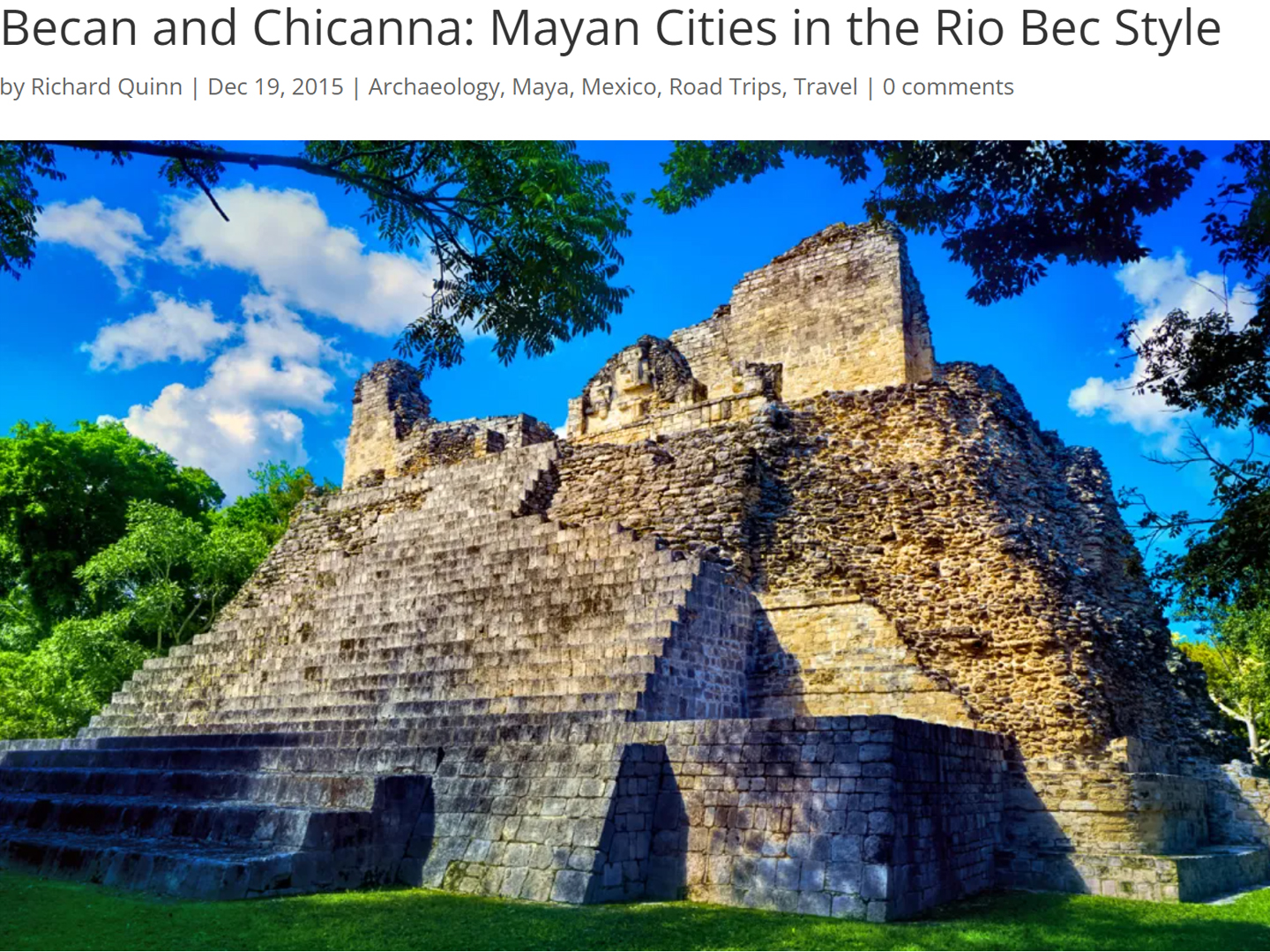

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. “Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins” was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after “Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali.” We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments