Through the course of this series I’ve been referring to the Tumaco Culture as if it was a single, clearly defined native population, but that isn’t exactly the case. The area inland from the Pacific coast, north and south of Colombia’s present day border with Ecuador is rife with archaeological remains, and while there are a great many similarities in the artifacts that have been exhumed, there are also many differences, some so extreme that they have to be considered an entirely seperate cultural phase. There were settlements of all sizes, loosely connected from a cultural standpoint, but it’s not likely that there was ever a significant level of unifying political alliance.

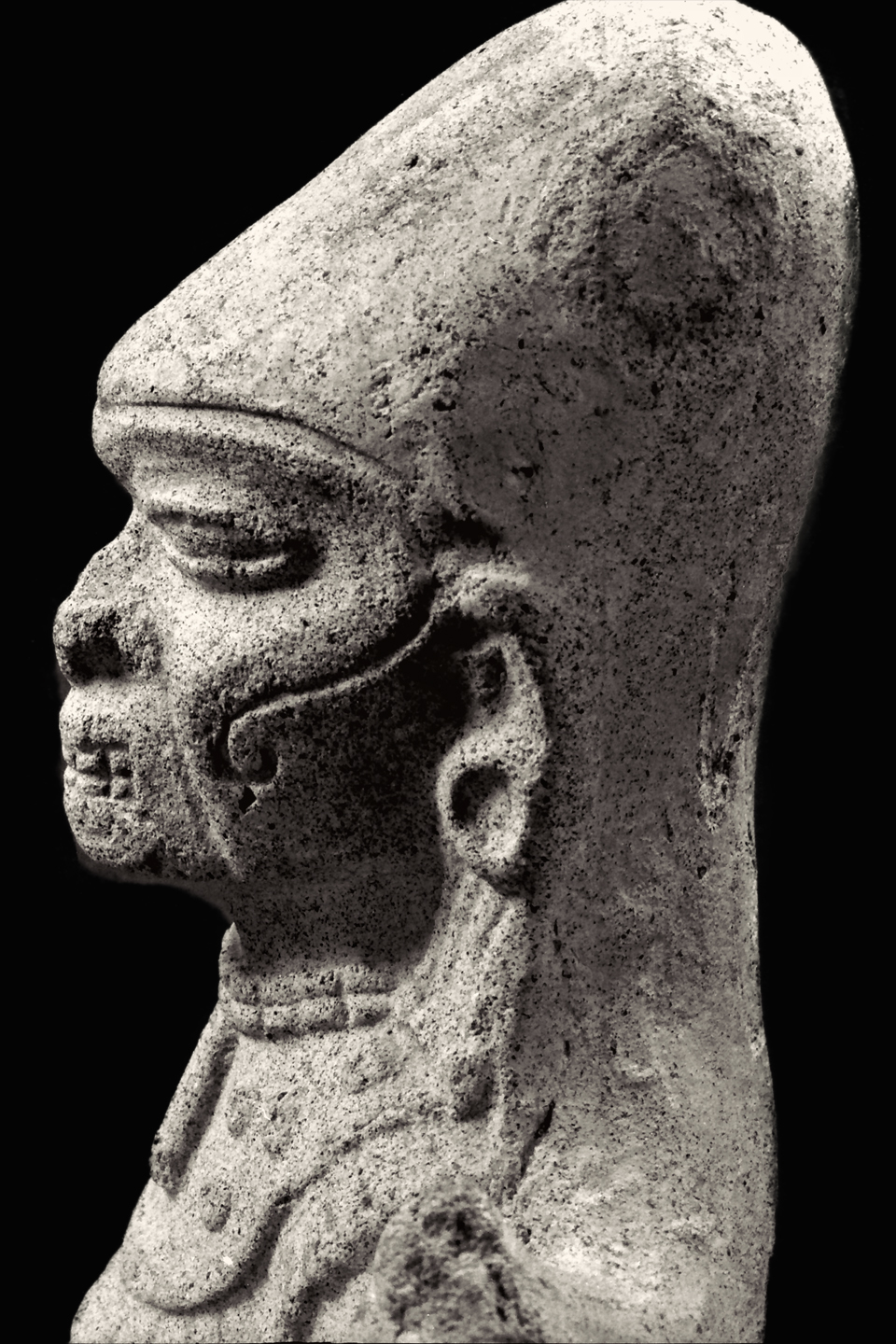

One cultural trait that they did all have in common was the value they placed on craftsmanship. The Tumacan goldwork that has been recovered is widely considered some of the finest in the ancient Americas. Extraordinary examples grace the collections of some of the world’s most prestigious museums, while many others have gone on the auction block in Paris, New York, and London, where they sell for tens, if not hundreds of thousands of dollars. No one seems to mind the fact that these treasures, almost without exception, were dug up by grave robbers, known locally as guaqueros. Nor does anyone seem bothered by the wholesale destruction of the archaeological sites from which these precious items were removed. Gold has a peculiar gleam that tends to blind men’s eyes to such niceties, so that battle was lost from the moment that first gold mask came to light, shining up from the muck of a burial mound, alongside the Mira River.

Tumacan gold, photos from multiple sources on the Internet

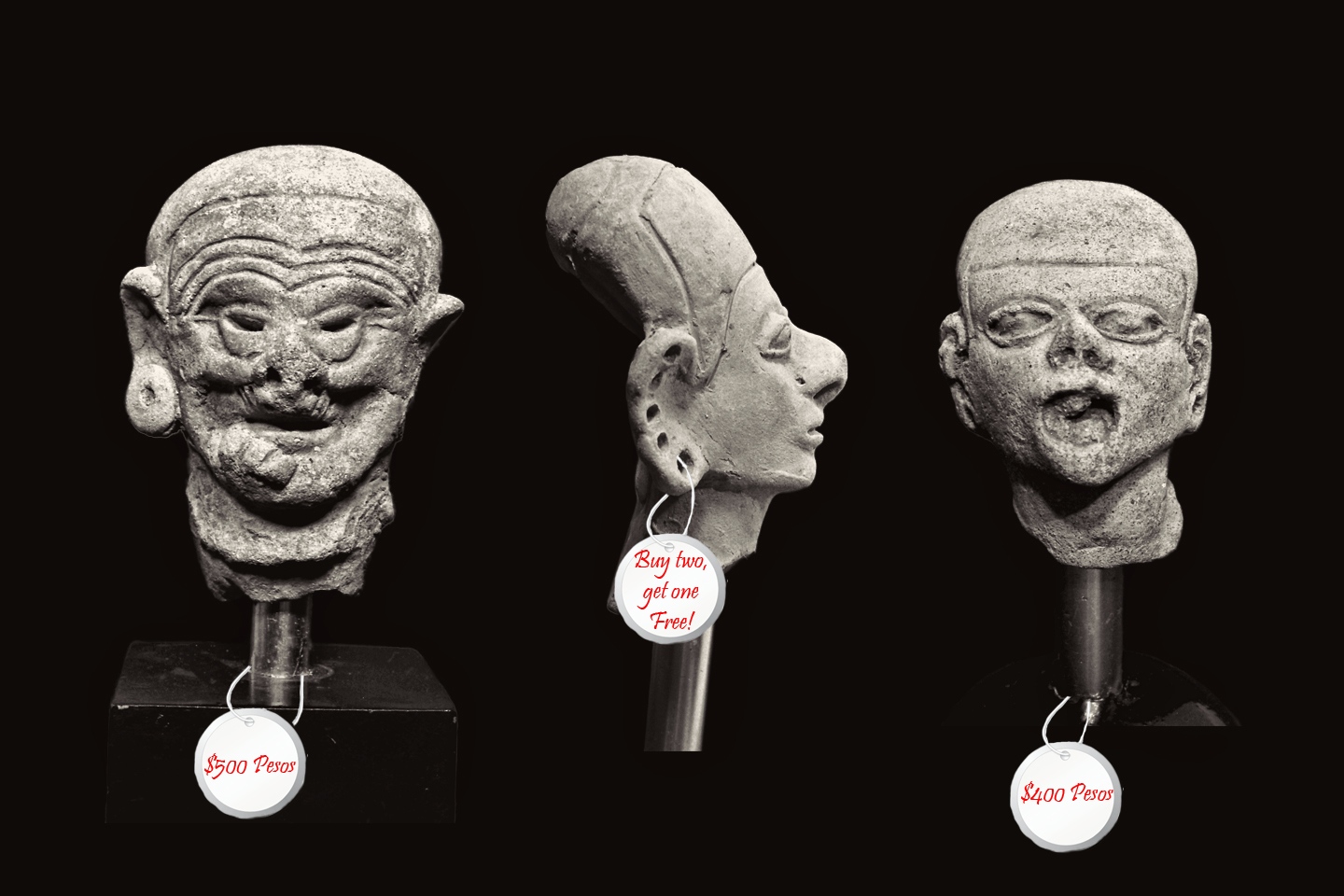

Those first discoveries started a literal gold rush of grave robbing wannabes, and like every other gold rush in history, the losers who found no gold outnumbered the winners, a hundred to one. A big difference in this case: even the losers got a consolation prize. There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, every bit as well made as the gold artifacts that had created such a stir, and unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen:

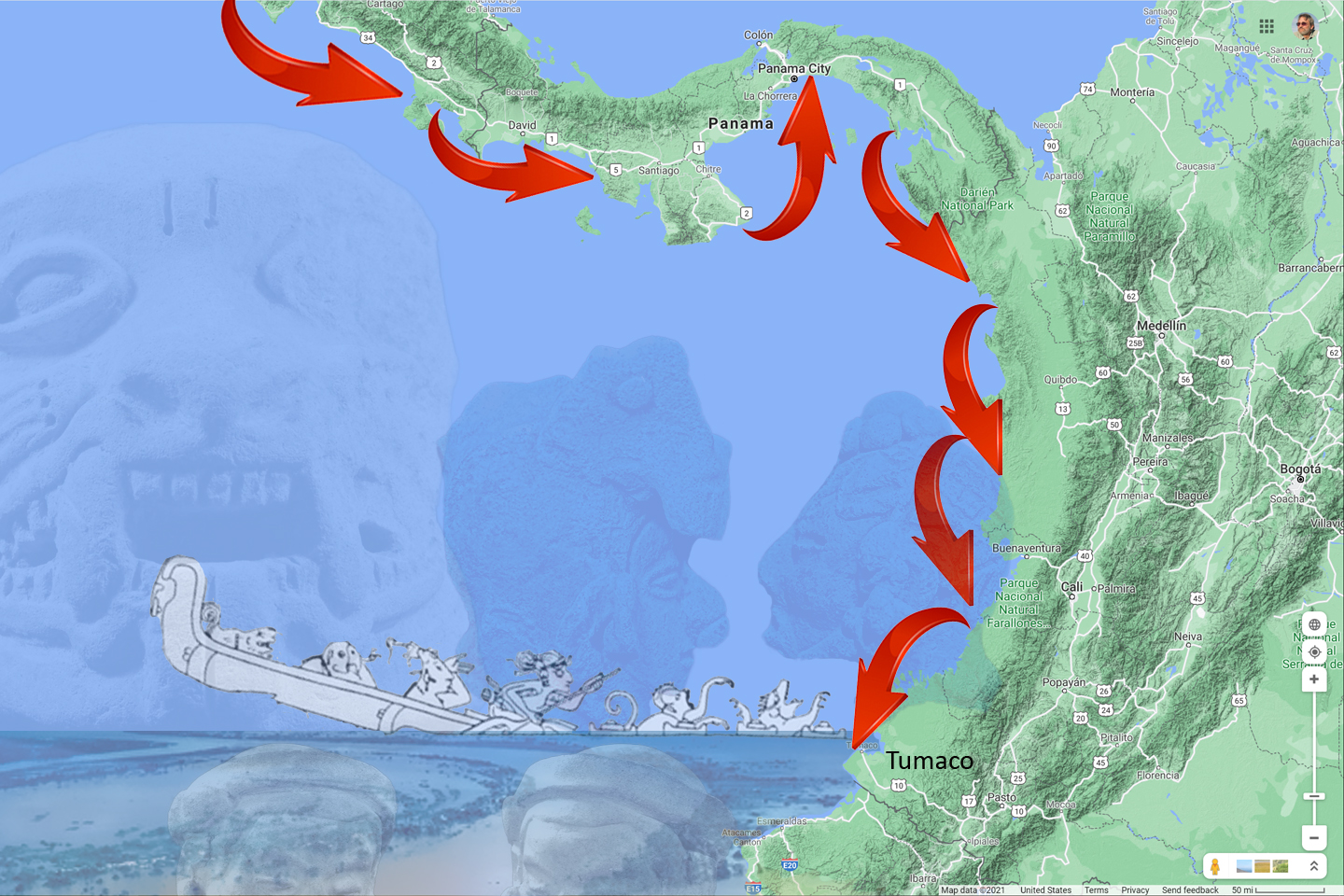

The better-known ancient cultures of the Colombian highlands–the San Agustin, the Calima, and the Quimbaya, to name just a few–incorporated similar animistic styles into their art, but that was later on, and it’s apparent that they were influenced by a renaissance of sorts that can be traced to Colombia’s Pacific coast. Something happened in Tumaco, around about 900 B.C., something that had a profound and lasting effect on the people who had been living there. According to the popular consensus, men from Central America traveled south, following the shore in seaworthy canoes, and they brought with them seed corn, fine textiles, and the fearsome cult of the jaguar, the most powerful animal in the jungle.

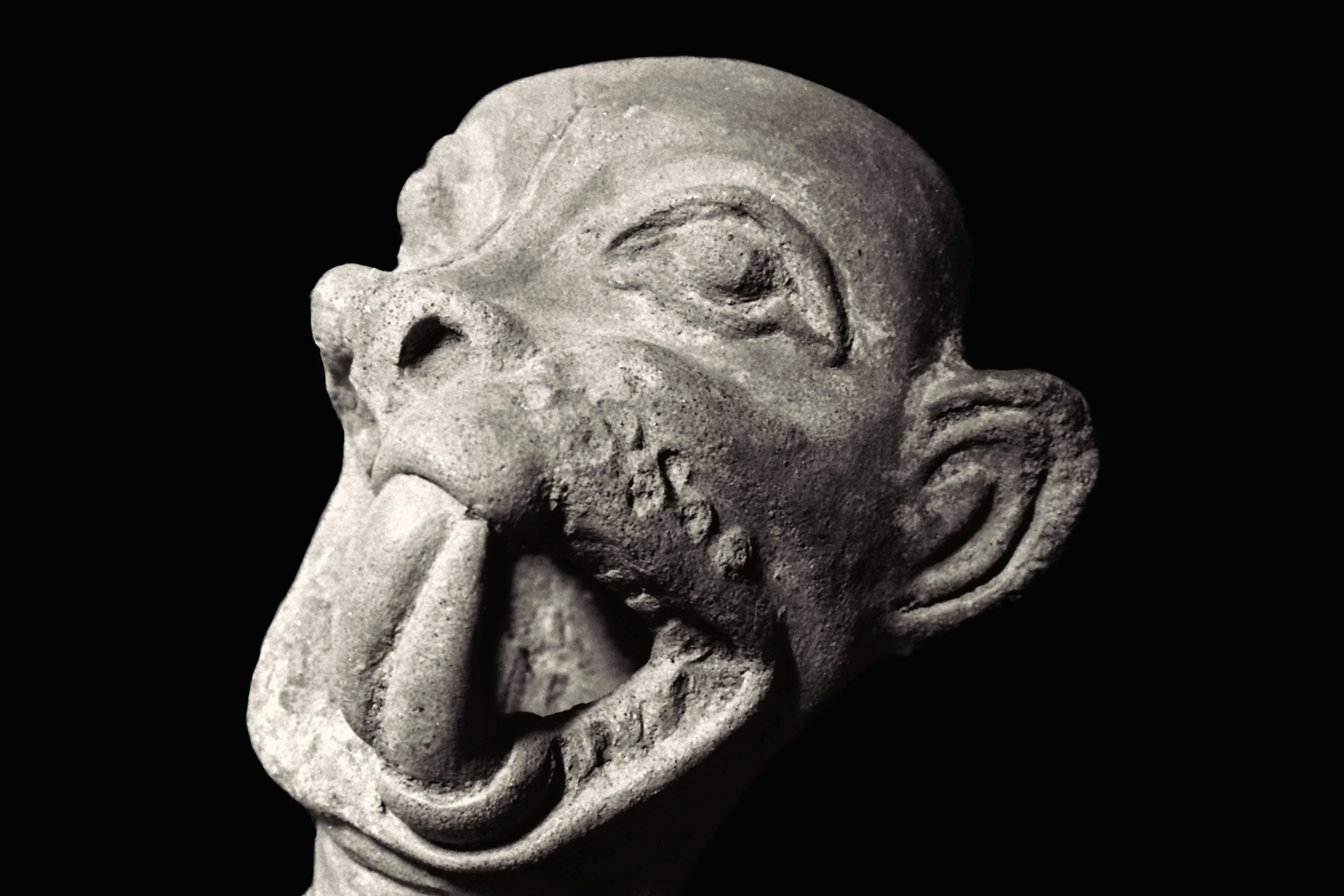

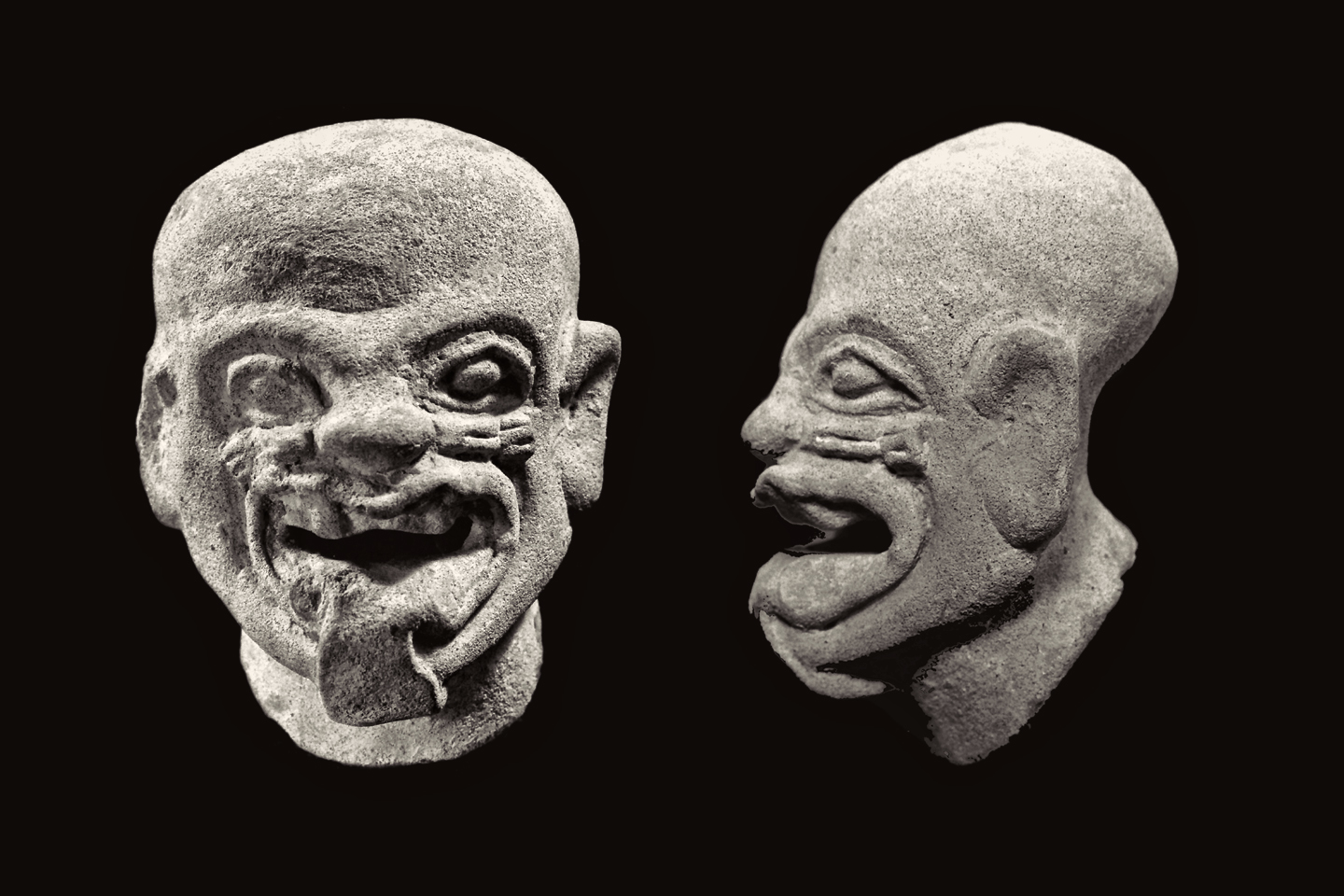

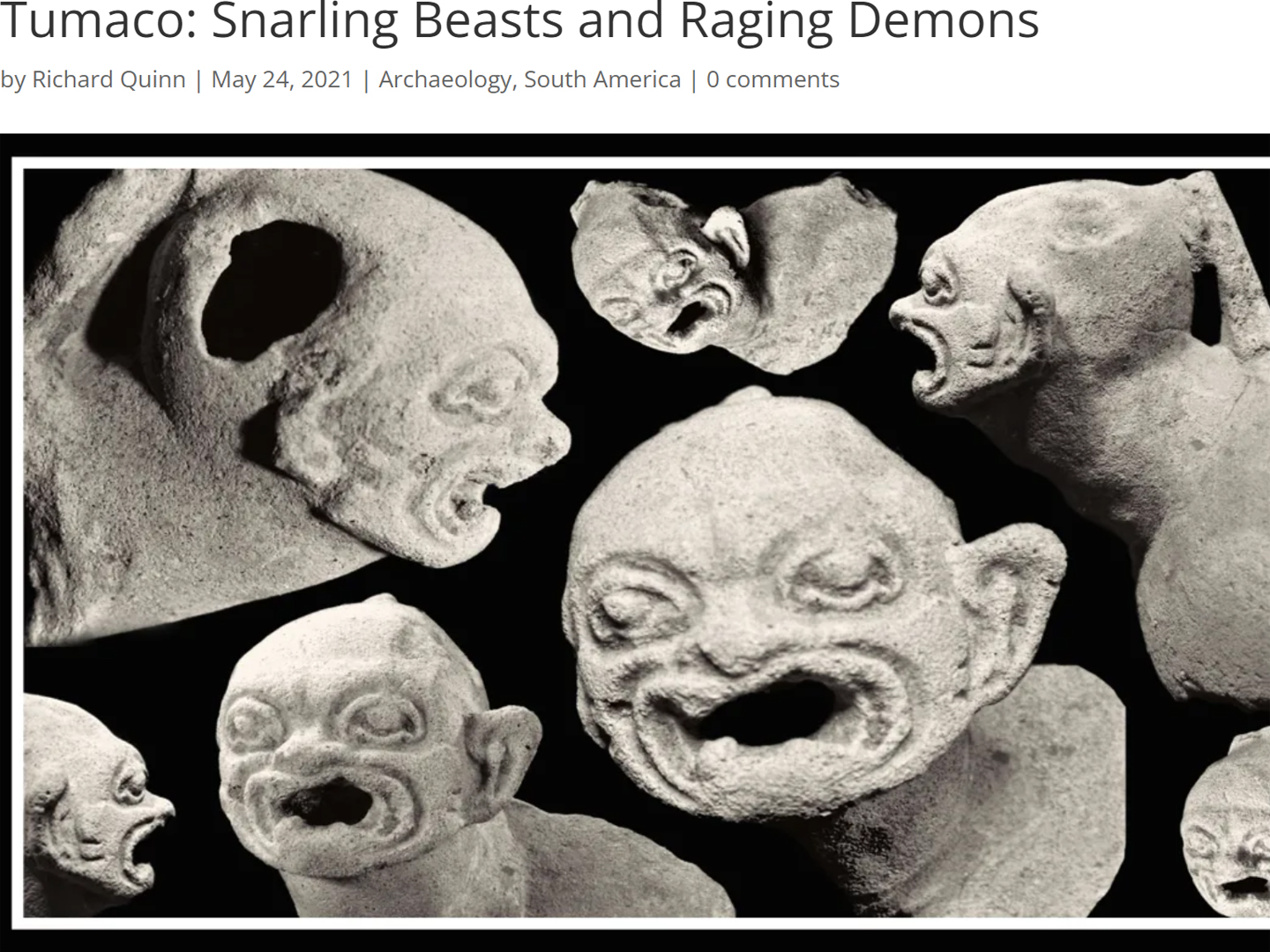

Along with Ek Bal, the great cat came a whole retinue of mythical creatures with fangs and long, curling tongues, and it was most probably the men from Mexico who taught the Tumacans the art of fashioning figurines from the local clay, figurines and masks meant to honor the snarling beasts in their new pantheon:

Many scholars believe that the Mesoamerican influence on Tumaco culture was much too strong to be explained by casual contact with traders. Rather, there must have been colonists, fully developed communities of laborers, craftsmen and teachers who emigrated from Central America and settled along that coast, spreading their influence across multiple generations, throughout the northwestern sector of the continent. Maize is known to have existed on the South American continent prior to this time, but it was the emphasis on maize agriculture by these emigrants that revolutionized the social structure of every culture touched by it. The surplus from the harvest could be dried and stored, and was far less subject to rot than their other crops. A consistent, reliable food supply enabled technical and social innovation, and the men from Central America provided guidance; the jaguar’s influence was felt everywhere there was corn.

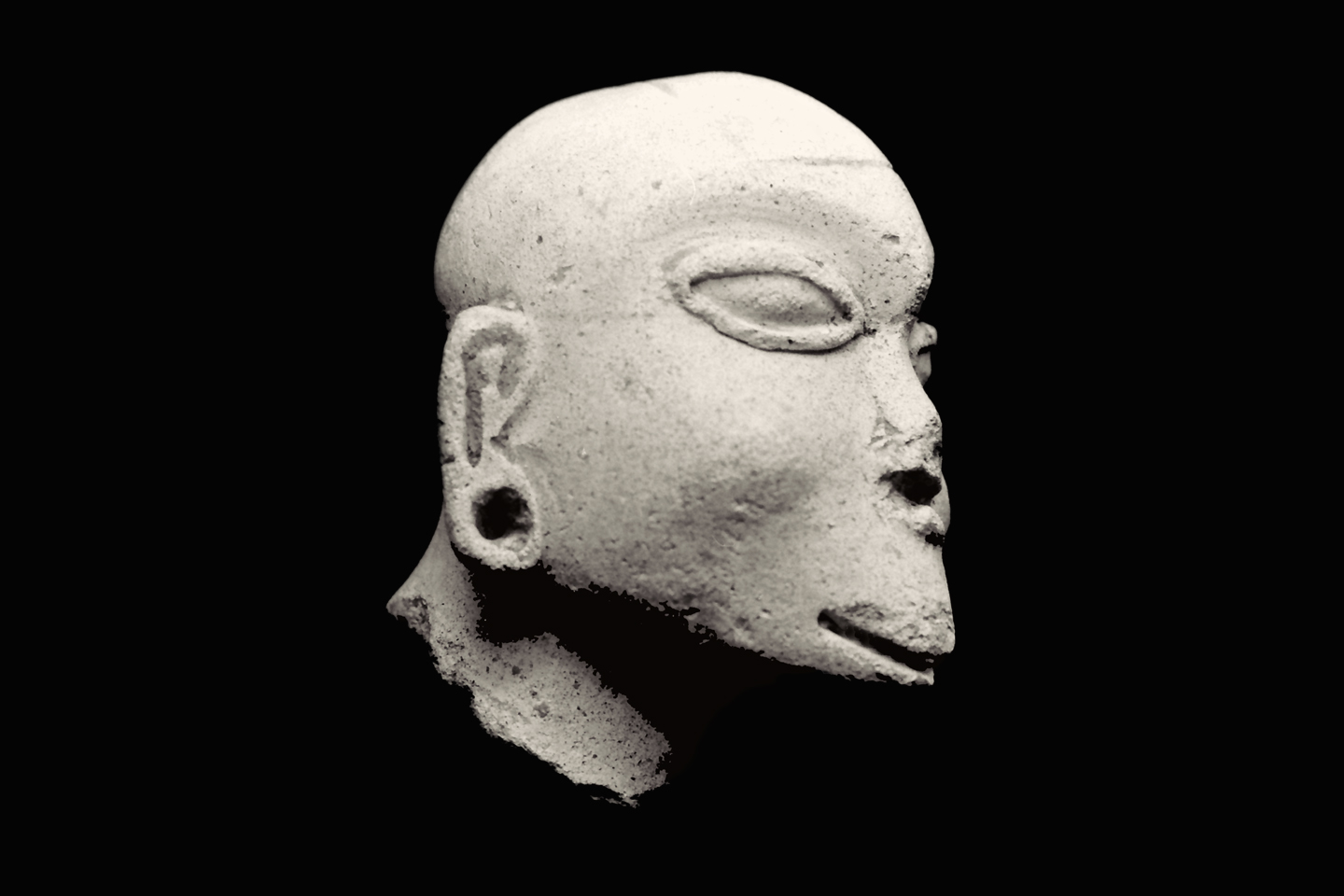

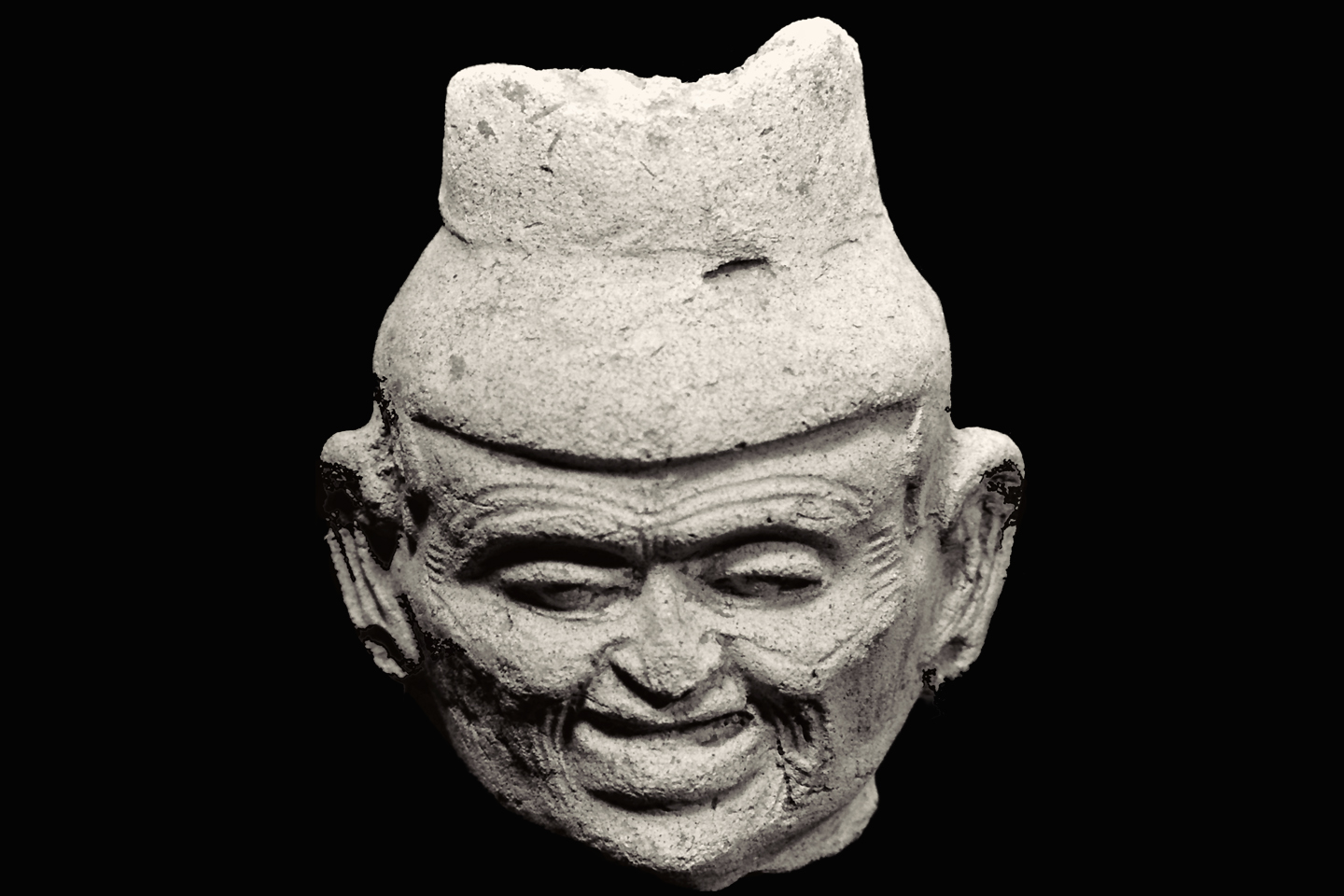

Tumacan craftsmen excelled at the manufacture of ceramic figurines, and over time, they created representations in clay of all the creatures in their world. Many of them were real animals that could be seen, and hunted, while others existed only in the visions of their shamans. Creatures from the world of dreams were half animal, half human. There were monkeys and otters, as well as kinkajous, sized smaller than the others, just as they would be in real life. Iguanas and crocodiles stand on two legs, and they have human arms and hands, along with expressive faces. Most of the animals have extended tongues, and sharp teeth bared in a snarling grimace.

The more fantastic creatures wear human clothing and ornamentation; tunics with breastplates, necklaces and collars, crowns, clasps for long hair in braids. These creations are not random works of art, rather, they are highly stylized representations of specific mythical entities, and every aspect of each figurine conforms to a rigid standard.

The two examples pictured in the slideshow below represent different phases of the Tumaco culture, separated by hundreds of years. The artifact on the left in the first photo is from the Tumaco area, while the piece with the outstretched claw, based on the composition and coloring of the thin-shelled clay, hails from further south. Is one a frog, and the other a feline? Both figurines have round eyes, a circle within a circle; both have large fangs on either side of an extended tongue, framed within pulled back lips. In both figurines, we have a snarling creature that seems almost benign in its rage, dressed for the occasion in a crown that is perhaps set with gold, or possibly with gems. Both creatures have long hair tied on either side of the head with decorative clasps; both wear necklaces with multiple strands. When focusing on just the faces, there are enough similarities to align the two pieces, despite the obvious differences in style.

Most of the Tumacan artifacts that have been recovered are broken, and in many cases, it appears as though they were deliberately smashed before they were buried. There is widespread speculation that the figurines were used in shamanistic rituals such as healing ceremonies, or for observances related to their animistic religion. Smashing a figurine or defacing an image negates the power associated with it, and when you consider the sheer quantity of smashed figurines found near Tumaco, it’s apparent that they took that concept very seriously!

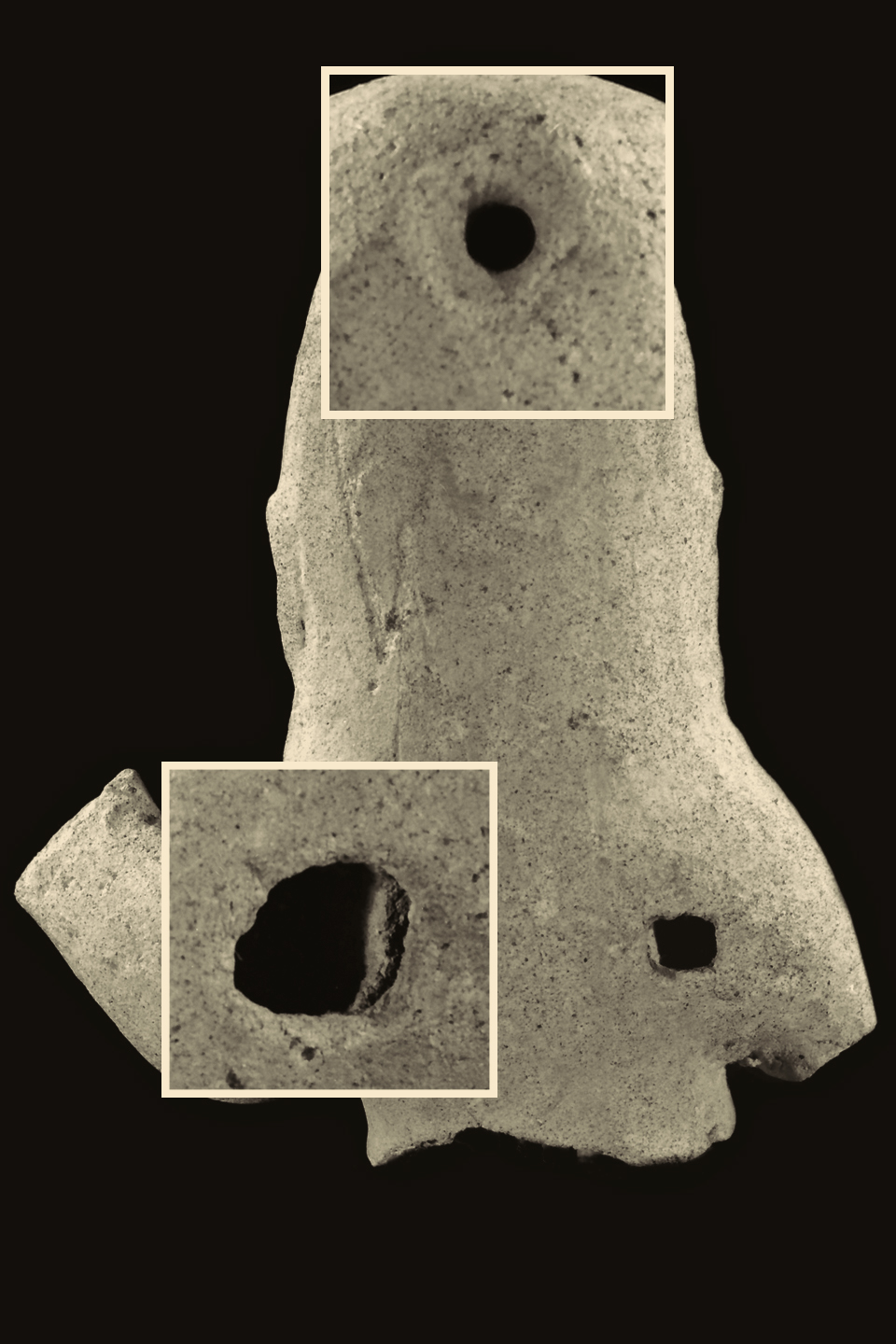

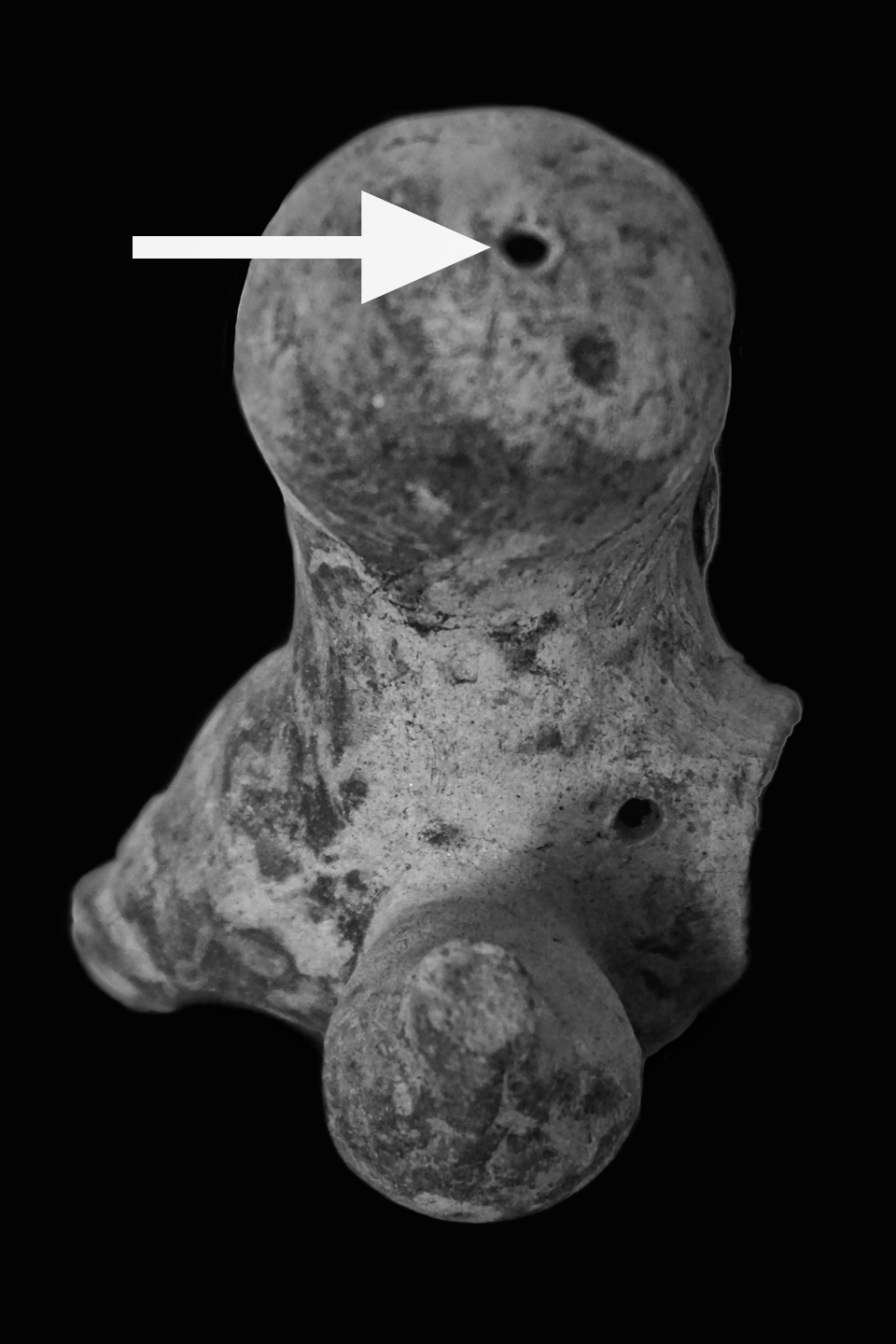

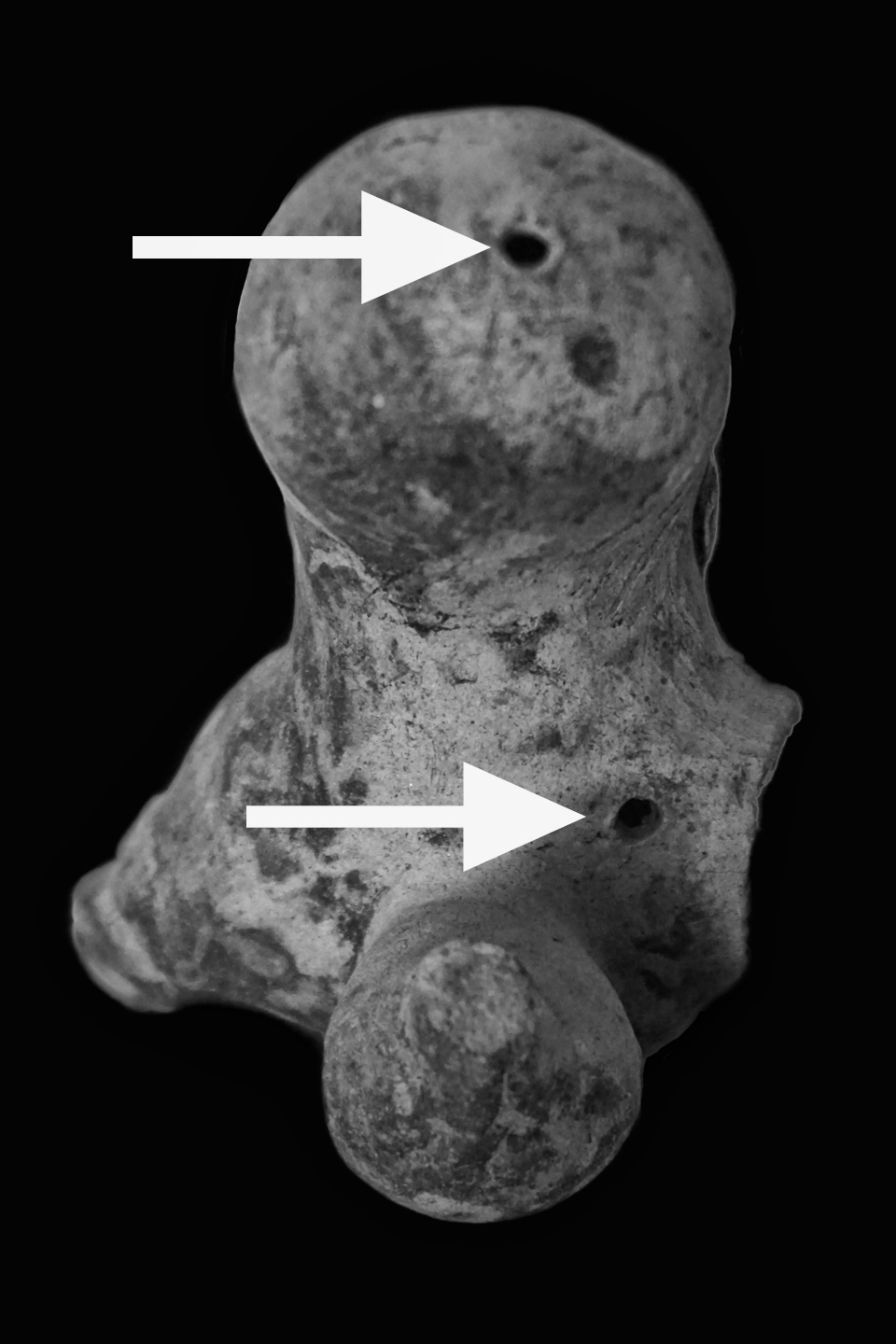

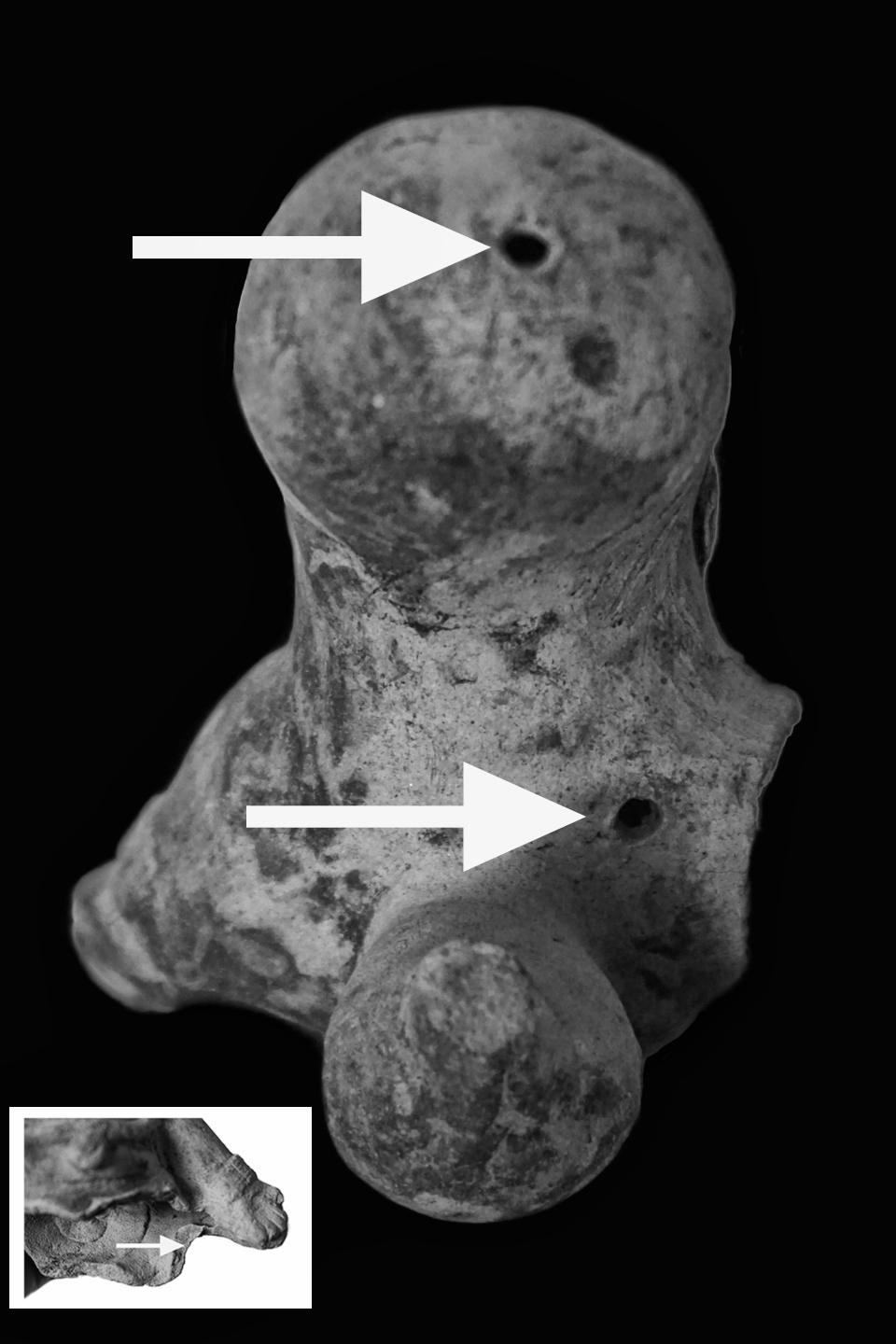

Most figurines were just that, small clay sculptures with no obvious utilitarian function, but at some point, a feature was added to some of them. The more sophisticated figurines are hollow, three dimensional, and they all have a hole, usually in the top of the head, that acts as an air vent when the clay is fired. By adding additional openings on the back side of the figurine, and carefully shaping them at an angle, the finished piece becomes a whistle when you blow through the top hole. In some cases, one or more additional holes were added, and these could be covered and uncovered with a finger to modulate the tone.

In the photo collage below, there are two examples of Tumacan whistles. The first is a woman with teeth bared in a grimace. When the figurine is viewed from the side, the woman appears to be pregnant. The hole in the top of the head is well shaped to serve as a mouthpiece, and there are openings on either side that produce the shrill tone. This one is sufficiently intact that if you cup your hand against the bottom of the piece, tightly enough to make a seal, the whistle still works.

The second example is a simian creature with pursed lips and a comical countenance. There is one hole in the top of the head that serves as a mouthpiece, and a second hole below the shoulder that modulates the tone. The figurine broke just above the openings that produced the tone, leaving nothing but the carefully beveled edges to identify the piece as a whistle.

Colombia is a Catholic country, and the guaqueros who dug up most of the artifacts in the Tumaco area were uneducated, but devoutly religious. Digging the graves was not a sin, because the Indians were heathens, and the burials were not consecrated. They tried to be respectful, but only to a point: if bones got in the way of their search for gold, the bones were tossed aside with the dirt.

The thing that DID bother the guaqueros? The demoncitos, the little devils; the figurines that looked truly demonic gave those superstitious grave diggers the willies. To hear them tell the tale, they should not have disturbed those little devils, because the evil powers they unleashed are the cause of all the tragedy that befell Tumaco in later years. And who knows? They might actually be right!

~~~~~

Disclaimer: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff, but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen:

If you’re interested in the Tumaco Culture, check out the rest of the series, beginning with Tumaco: Part 1: Atrocity Tops Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia.

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Tops Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

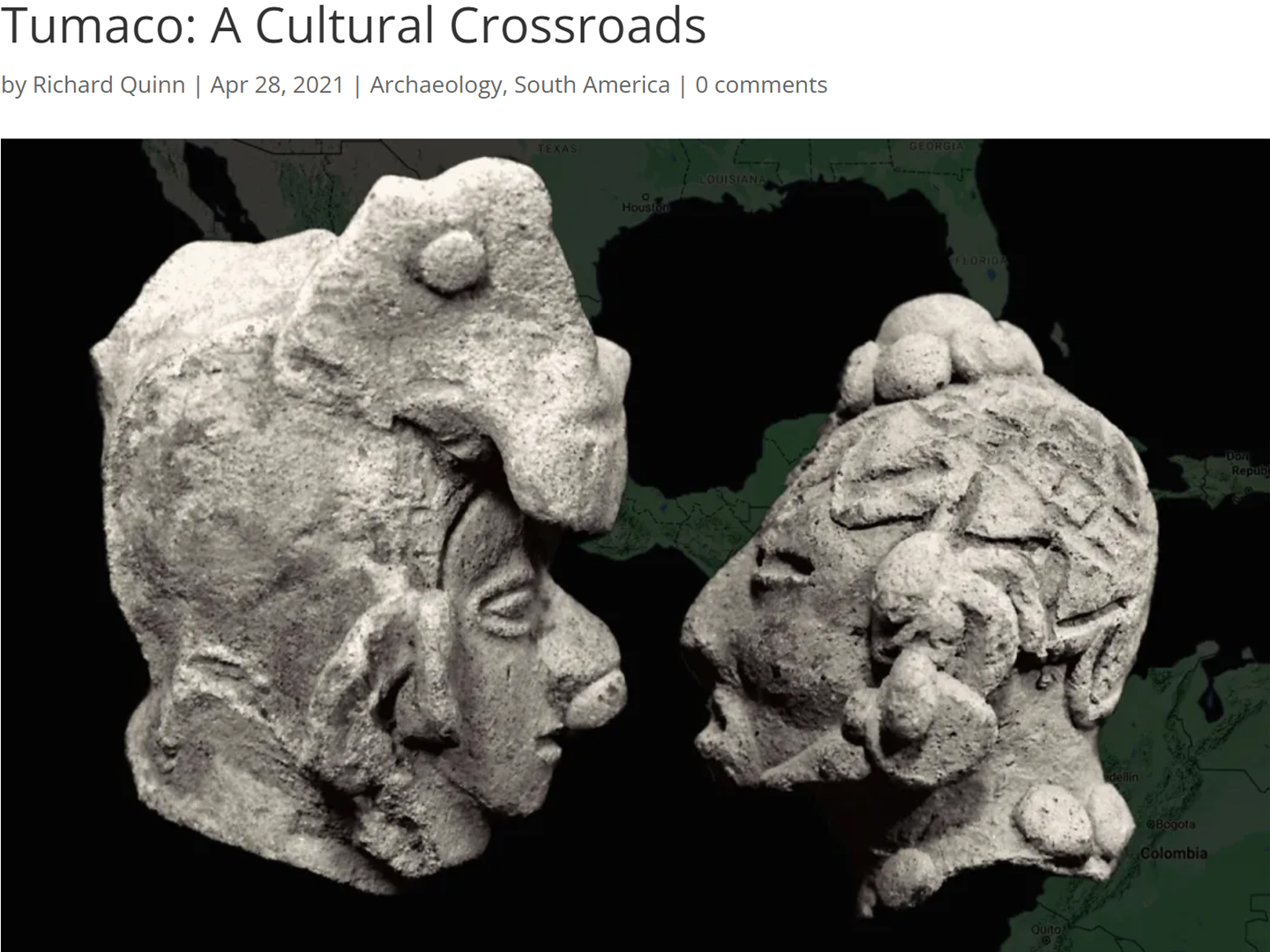

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

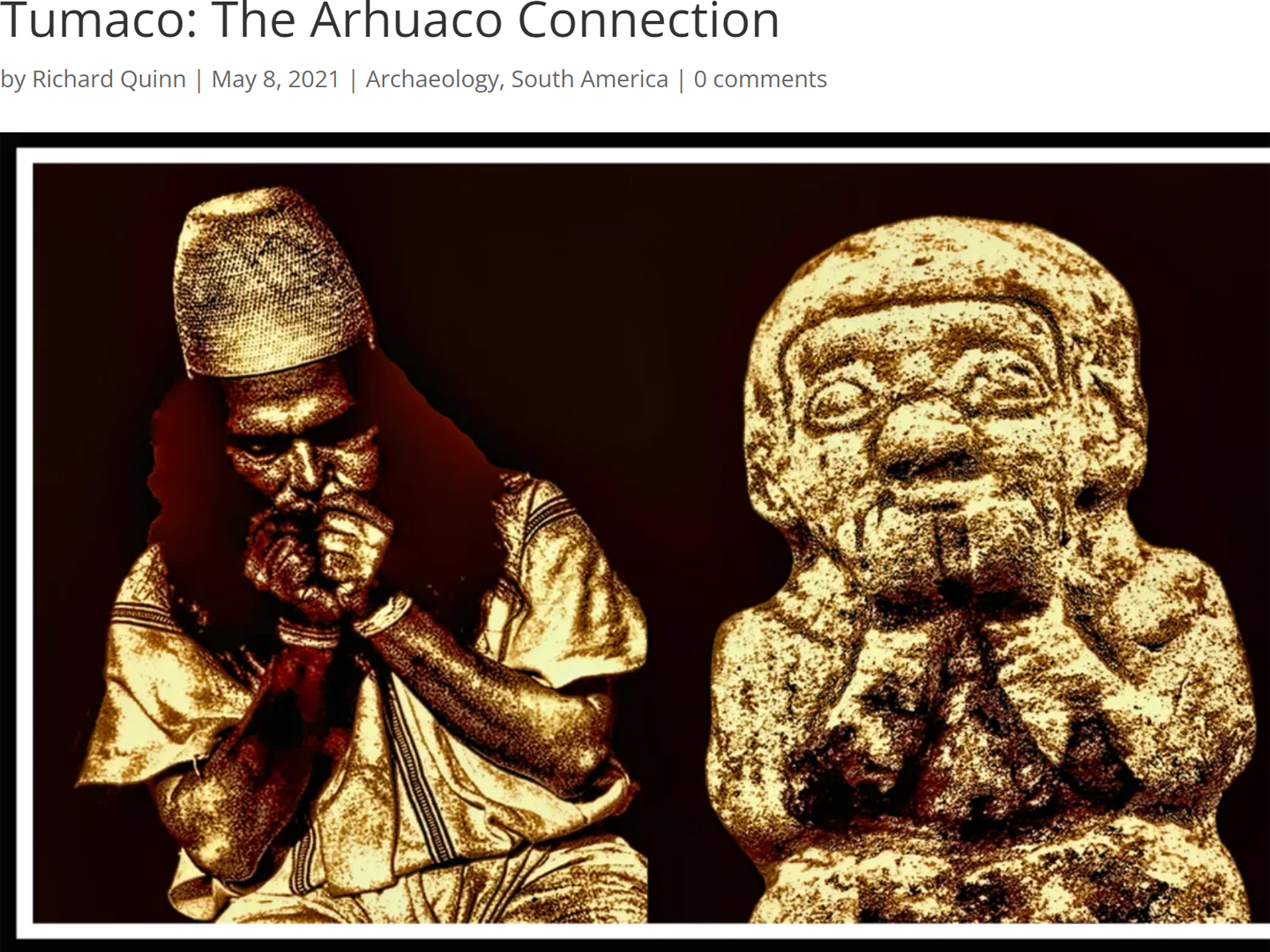

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments