Click any map or photo to expand the images

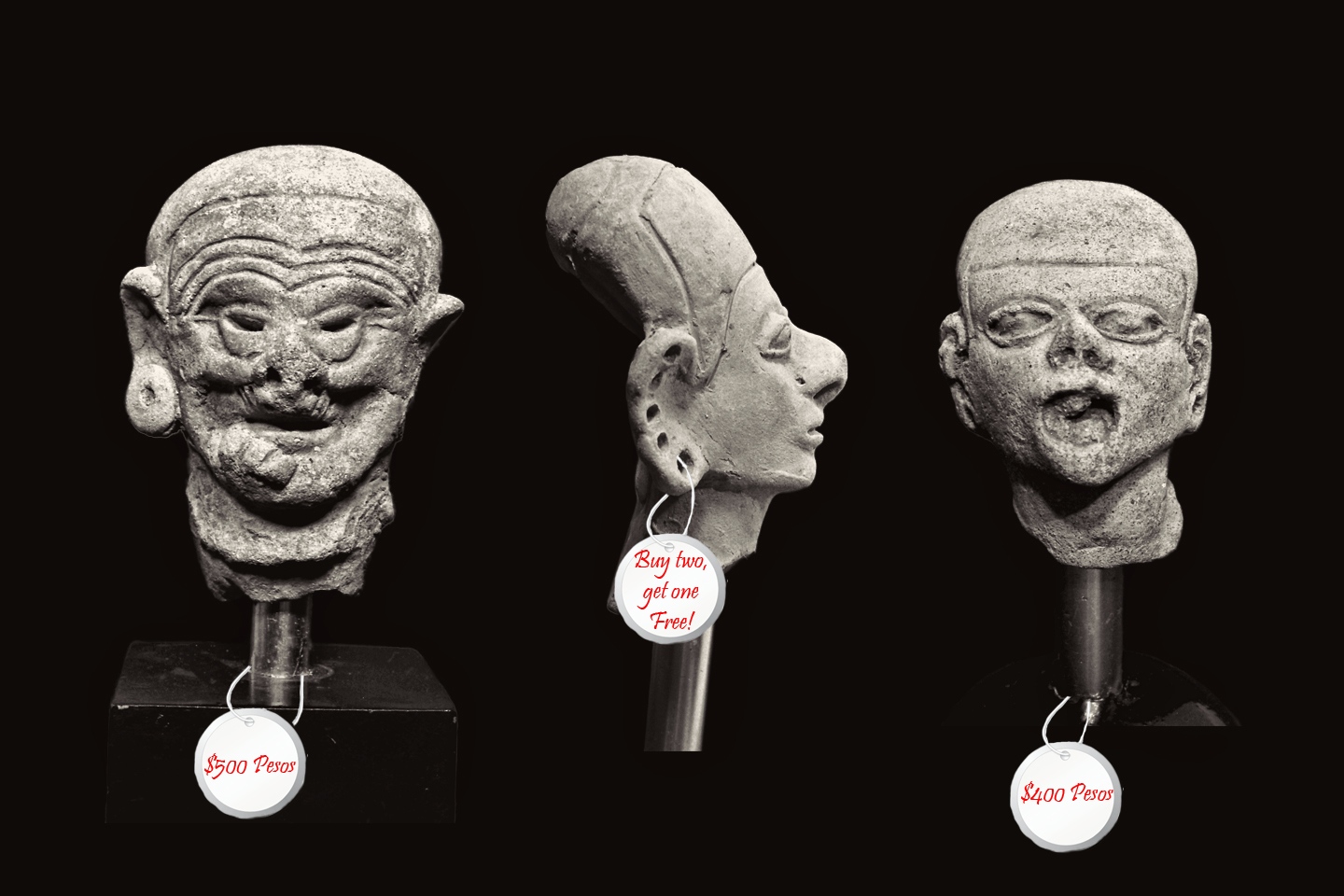

When I was living in Colombia, in the early 1970’s, pre-Columbian artifacts were a commodity, a form of luxury goods for the amusement of wealthy travelers. The best hotels had jewelry stores right off their lobbies, featuring spectacular Colombian emeralds set in brooches, rings, and bracelets, and right alongside the sparkling modern creations were necklaces made with carved carnelian and jade, centered with cast gold pendants fashioned by Tairona artisans as much as a thousand years ago. Brightly lit display cases held fine examples of authentic ancient gold work, surrounded by ancient ceramics from a dozen different prehispanic cultures. All of it was available for sale, and it was perfectly legal to take it home with you to the U.S., or just about anywhere else.

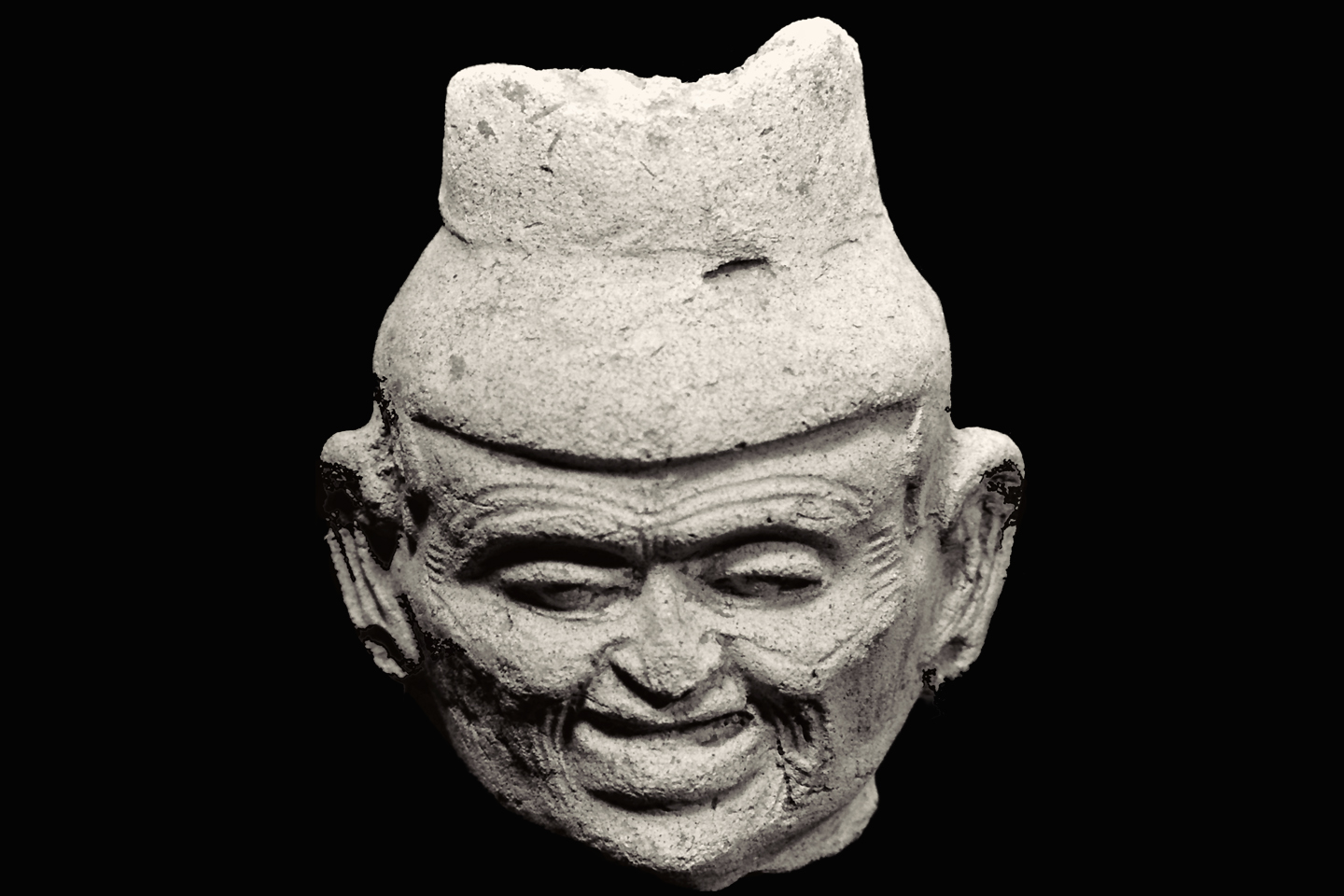

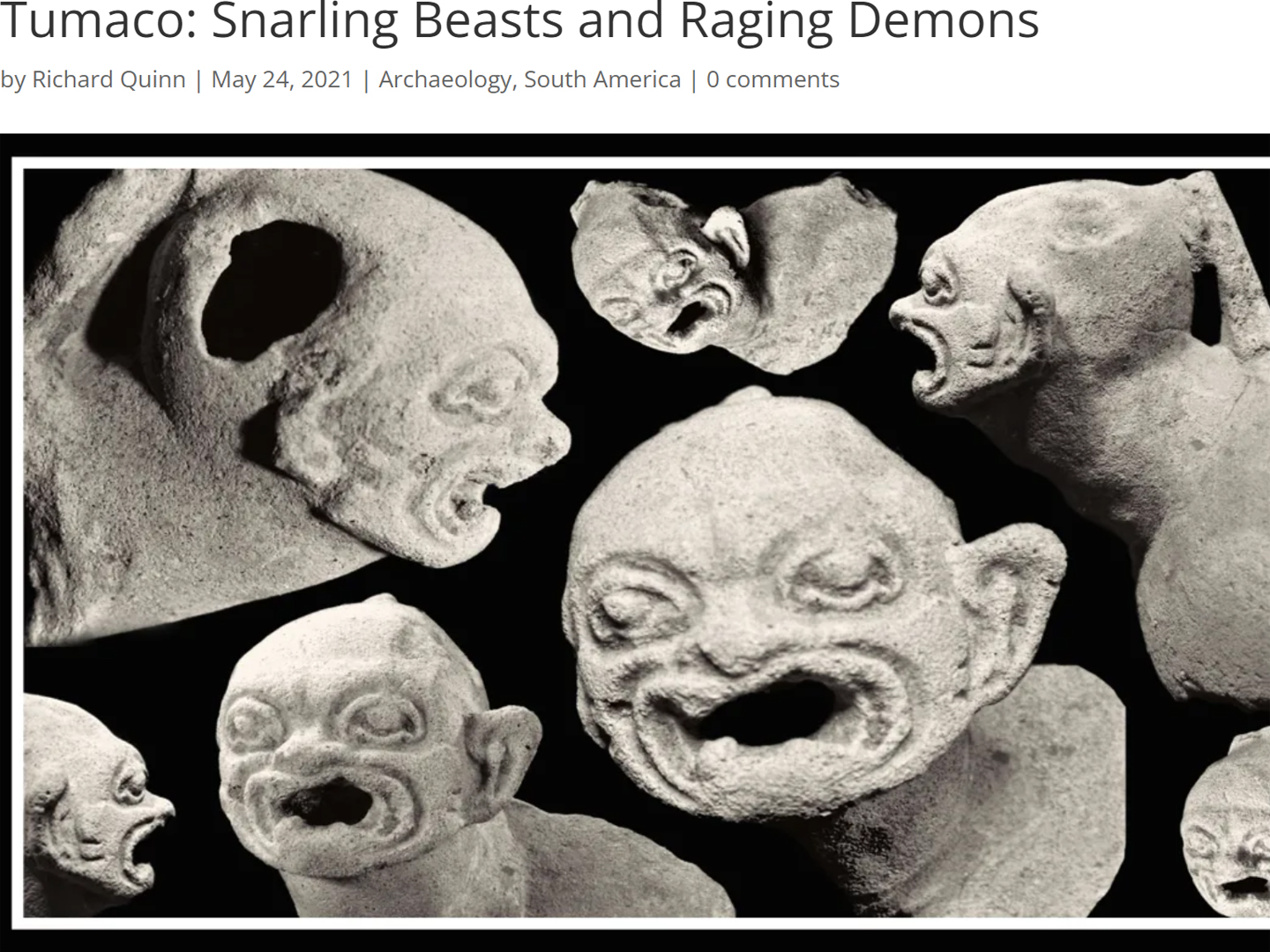

I used to browse through those shops whenever I was in Bogotá, because the inventory was constantly changing. The pieces from Tumaco fell into broad categories: little men with fitted caps and globular nose studs; feline demons with whiskers and long curling tongues; beasts with human attributes and prominent fangs. There were many fine examples of those basic types, but what I was most interested in were the oddities, figurines that were different from all the others. I also looked for congruencies, alternate versions of the same entity, or activity. That might sound like a sophisticated approach, but it was actually very simple: if an artifact piqued my curiosity, I took a picture, and added it to my files.

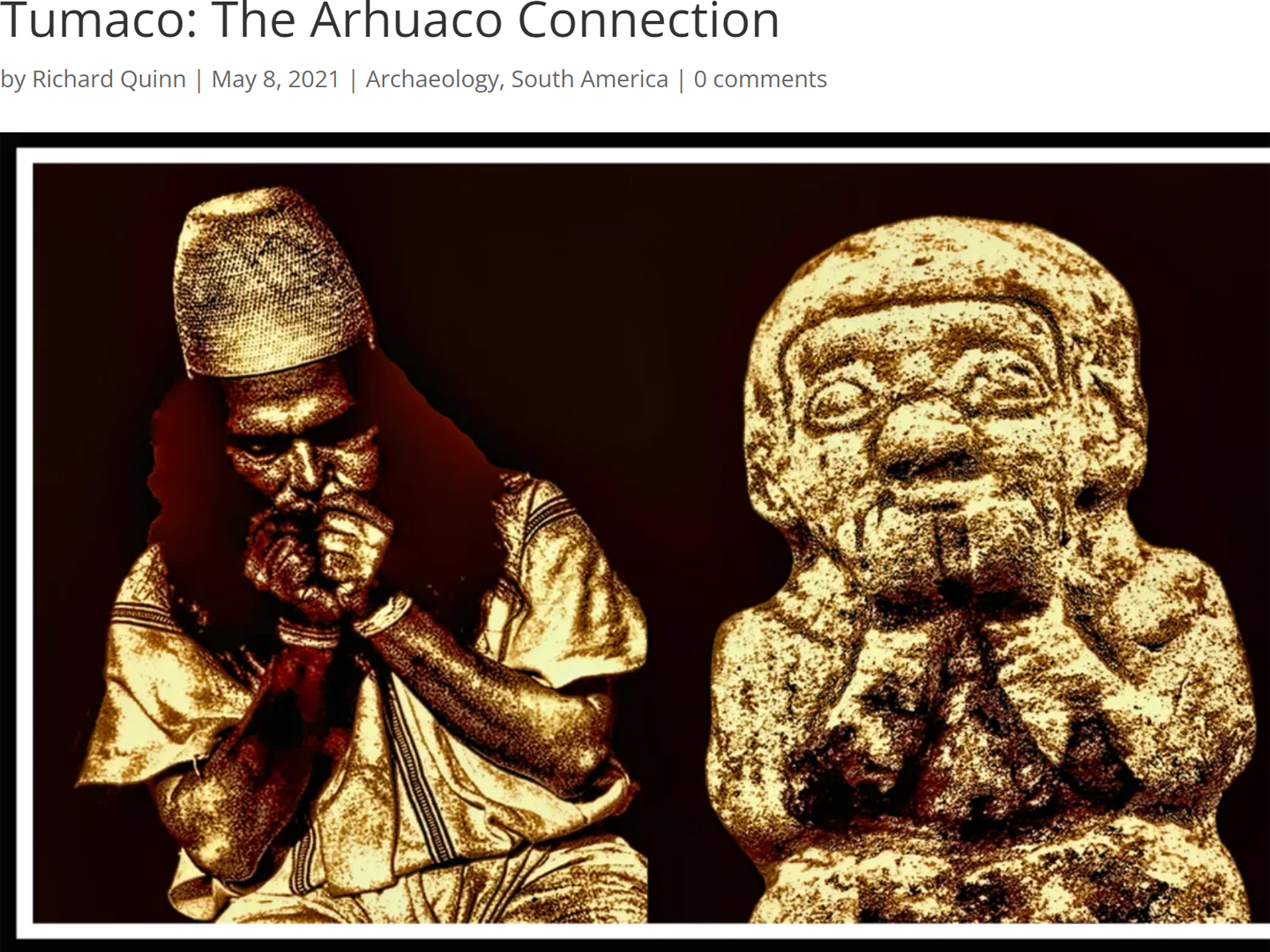

This palm-sized piece (below) struck me for what I thought was a charming display of humanity, an expression of surprise, hands to face, as in “Oh, my goodness!” A year or more later, browsing in a different shop, I ran across a second figurine, similar to the first, but in that one, the little man appears to have something in his hands, which I jokingly referred to as a harmonica:

It’s hard to tell, because the features are quite worn, but either way, there was a common theme of “hands to face.” Both figurines were similarly adorned, wearing a fitted cap and bracelets on their wrists. What could it possibly represent?

For the answer to that question, follow along on a journey that will take you to the Heart of the World, on the opposite side of Colombia, and half a century into the past.

ANOTHER TALE FROM THE ARCHIVES:

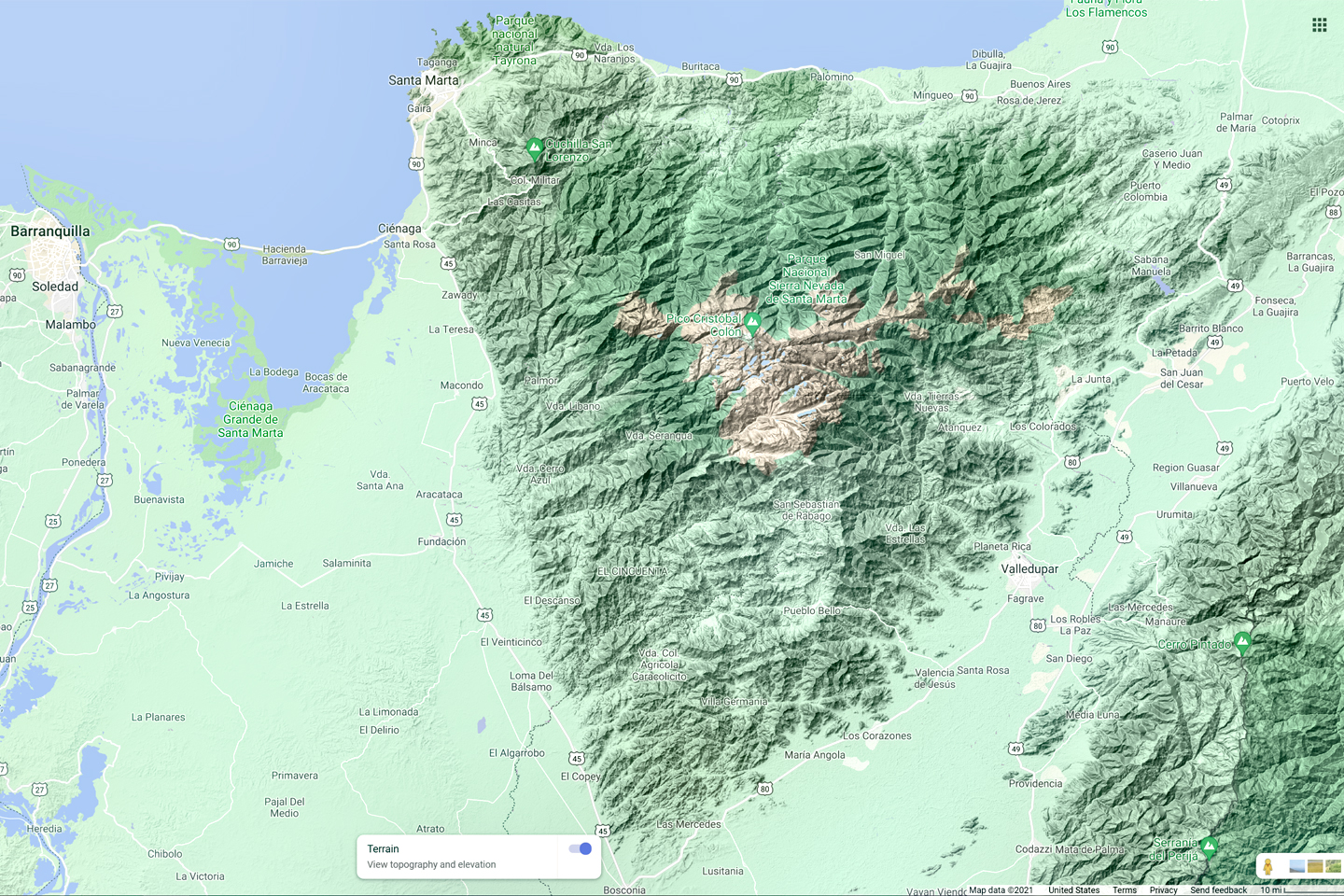

In October of 1973, I accompanied a friend, Stewart Royster, on a visit to an Arhuaco Indian village on the southern flanks of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the mountains on Colombia’s northern, Caribbean coast. This was a rare opportunity, because the Arhuaco territory was closed to outsiders. Stewart was a working anthropologist, a Fulbright scholar, and he was welcome because he had friends in the village. I was welcome, but only conditionally, because Stew had vouched for me.

The Arhuaco are descended from the same roots as the Tairona, a relatively advanced and quite fascinating culture that occupied Colombia’s north coast up until the time of the Spanish conquest. Tairona warriors clashed with the men from Spain, and their reward for daring to fight back was total annihilation. Tairona chiefs and shamans were publicly executed, and their towns and villages were burned to the ground. Survivors, including the women and children, were rounded up and sent to the encomiendas, the colonial plantations, where they were literally worked to death, as a warning to the other conquered tribes. A scant handful of the Tairona escaped, and fled into the high Sierra, where they sought refuge among the isolated clans that lived on the edge of the sacred snows. They assimilated easily, ultimately blending with their hosts, because they all spoke dialects of the same language, and shared the core tenets of the same animistic religion.

Besides the Arhuaco, there are three other tribes still surviving in those mountains: the Wiwa, the Kankuamo, and the Kogi, all of them tied to the Tairona, culturally, and spiritually. In the 400 years that have passed since the conquest, the Indians of the Sierra have aggressively avoided most contact with the outside world, and they have good reason for their bad attitude. Collectively, through their legends and traditions passed down from one generation to the next, they remember that one-sided war with the Spaniards as if it was a recent event, and they frame their relationship with all outsiders through the lens of that atrocity.

The Spanish, from the very beginning, wanted their gold, and had no qualms about killing for it; hiding away in their mountains was the only way the Indians could protect themselves. The Franciscans came next, presenting themselves as peaceful benefactors, there to help the Arhuaco improve their lives, but it was a trick; the deceitful padres wanted nothing less than their souls! And now, in modern times, there were colonists, poor Colombians who needed land, and weren’t at all remorseful about taking land that belonged to the Arhuacos. They could almost be forgiven, if there weren’t so damned many of them, and there was a sinister thread in that current: many of the illegal homesteaders were planting fields of marijuana on Indian land, and they had the support of the rising class of wealthy drug traffickers.

For the Arhuaco and the other Indians of the Sierra, any incursion into their territory was a form of blasphemy. Their mountain home, centered on the perpetual snows of Colombia’s highest peaks, is the Heart of the World, a concentration point for the spiritual energy that keeps the entire planet vital. The Arhuaco priests, called Mamas, are the custodians of those forces, and they are the cultural equivalent of the high lamas of Tibet. Among their people, and in their place, they are immensely powerful, but when pitted against the forces of the modern world, they wither, and fade. The Mamas were wise enough to know that, and they’d called on Stewart, one of their only Anglo friends, to help them get the word out to anyone who would listen, and pressure the government to stop the land grab.

When Stewart and I first met, earlier that year, we talked about all of that, and I, the bright-eyed, naïve young college student, suggested that we make a documentary film. Nothing too elaborate, but shot in the spectacular setting of the Arhuaco territory, with the Indians themselves making a plea for assistance. I wasn’t a filmmaker and I had no experience with that sort of thing, but I knew a guy with a 16 mm Bolex, and that was good enough for Stewart. He made a special trip to the Sierra just to sound them out about it, and this trip with me was the next step.

We took a train from Bogotá to the frontier town of Valledupar, where we secured the permits we needed to enter Indian country. From there, we boarded the local version of a jitney, a pickup truck with wooden benches in the open bed, and that thing took us up, bouncing along rough dirt roads to Pueblo Bello, “Beautiful Town,” the end of the track, and the last non-indigenous settlement before the Arhuaco territory. It was late, so we stayed the night there, sleeping in hammocks in someone’s back room, and started out the next morning at dawn, to a loud chorus of crowing roosters. Stewart bragged that he could make the hike to San Sebastian, our destination, in as little as three hours. As I recall, it took us closer to six, mostly because of me needing frequent rest breaks.

The walled village of San Sebastian de Rabago

San Sebastian, which the Arhuacos called Nebusimake, was a walled compound nestled in a high valley, surrounded by barren hills that were sadly denuded by overgrazing. The only gate though the wall was kept permanently closed, a symbolic gesture reflecting the Arhuaco’s attitude toward the rest of the world. The Indians propped a notched log against the wall next to the locked gate, and they used that as a ladder to climb up and over. It was a minor inconvenience, because very few of them actually lived inside the walls. The village was an administrative and ceremonial center where tribal members got together, but only when absolutely necessary.

San Sebastian/Nebusimake, as it appeared in October of 1973

The rest of their time was spent in isolated homesteads. Each family clan had two of them: a high altitude home where they kept their sheep, and grew crops which require a cooler climate, as well as a second home, lower on the mountain, where they grew delicacies peculiar to the tropics.

High mountain homestead near the Arhuaco village of Nebusimake

We spent a profoundly peaceful week in the village, entirely disconnected from the outside world. Stewart traveled with a concert flute, an expensive instrument made of solid silver that he carried in a velvet-lined case stuffed in his backpack. Whenever he broke that thing out and played it, every Indian within hearing distance was drawn in, almost as if they were hypnotized. Stew played pretty well, and the sound, in that setting, was really quite extraordinary. He had built an easy rapport with the usually irascible Arhuaco, and I have no doubt that the flute playing was a major key to his success; the music had a language of its own that broke down barriers. If the discussions about our film project had gone half as well, this story might have had a very different ending.

We knew going in that the whole notion of a film would be a hard sell. The only thing that the Arhuaco disliked more than an outsider was an outsider with a camera, and up to that point in time, they had never allowed filming in Nebusimake. I kept my Nikon packed away while we were in the village, to avoid any appearance of disrespect; I regretted that later, of course, but at the time, it seemed like an important concession. There were bickering factions within the tribe; some who liked the idea of making a movie, but wanted to be paid for participating. Others sincerely believed that cameras were evil, and that having their picture taken would harm them, or diminish them in some way. The rest were mistrustful, just as they had always been, so they were unwilling to commit support to either side.

Stewart was already disillusioned, not just about our film, but about the value of all the hard work he’d been doing with the Indians, so his usual optimism was getting edged out by cynicism. Nobody really cared about the Arhuaco, so why go to all this trouble? No film, no matter how well made, was going to change what was happening to them, so in the end, it would just be another form of exploitation. Since the Indians couldn’t agree, he made a personal decision not to pursue it any further, and since his participation was key to the whole deal, that was the end of it.

At the end of the week, we came down off the mountain and parted company. Stewart was headed off to the deep jungle to visit the Motilon village where he’d done most of his field work, and I was headed to Peru, where I met up with another friend, and had a fine adventure on my second trip to Machu Picchu. The following spring, I wrote up my field notes, along with an outline of a screen play for the aborted film project, and a high-level analysis of the problems the Arhuaco were having with the colonists. I mailed all that to my professors at Antioch College; they accepted it as a somewhat unorthodox independent study, and gave me five academic credits for my efforts. That was exactly what I needed to complete my degree, so for me, there was a happy ending after all.

I never heard from Stewart again. He was one of many people I lost touch with over the years, but he was truly one of a kind, and I often wondered what became of him. I figured he’d gone into the ministry, or to medical school, two possibilities he’d mentioned to me. Or perhaps he’d ended up as a professor somewhere, teaching wide-eyed undergrads about the real-life adventures of an anthropologist in the wilds of South America. When I started writing this post, in April of 2021, I dug out my notes from that long ago trip to the Arhuaco village, and Stewart’s name was there, spelled out in my tight, blocky handwriting, the ink faded, bleeding through the paper. These days, when confronted with a name from my past, my first impulse is to run a search on Google, so that’s what I did, and what I found could not have been more of a shock:

THE COURIER-JOURNAL, Louisville, KY, November 29, 1973, Robert Stewart Royster, a 25-year old Louisville anthropologist, has died in Colombia, his family learned yesterday. The State Department notified the Rev. and Mrs. D. Powell Royster that their son died last Saturday near Bucamaranga. Royster has been working in Colombia with primitive Indian tribes…

That wasn’t much more than a month after the last time I saw him, and the sad news bridged the half-century gap like a time-traveling punch in the gut. I dug for details, and learned that he never made it back from his visit to the Motilon village. He was attempting to help some of the Indians who were in critical need of medical care, guiding a group of them out of the jungle over difficult trails, when he slipped and fell and was bitten by a snake, probably a bushmaster. Those snakes, endemic to that jungle, are among the deadliest in the world, so there was nothing anyone could do; a tragic end to a good man who deserved so much better. His parents found his journals among his belongings, and had them edited and published in a volume titled Unquiet Pilgrimage. It wasn’t what you’d call a best seller, so it’s long-since out of print, but I picked up a used copy on Amazon, and had the rather eerie experience of reading things I didn’t even know about my own long ago adventure, penned by a dead man’s hand… (Key the theme from the Twilight Zone: Doo-doo-do-doo…..).

If I’d known that my first visit to Nebusimake was also going to be my last, I would have taken at least a few more photographs, despite the unspoken prohibition. The Arhuaco are a visually striking people, particularly in their mode of dress. Men and women alike wear a woven white tunic, belted at the waist. On the women it’s like a shift that goes all the way down to their ankles, while the men’s version is shorter, with white trousers underneath. All men wear a traditional white cap, close-fitting, flat on the top, said to represent the sacred glaciers that crown the Sierra Nevada, their mountain home.

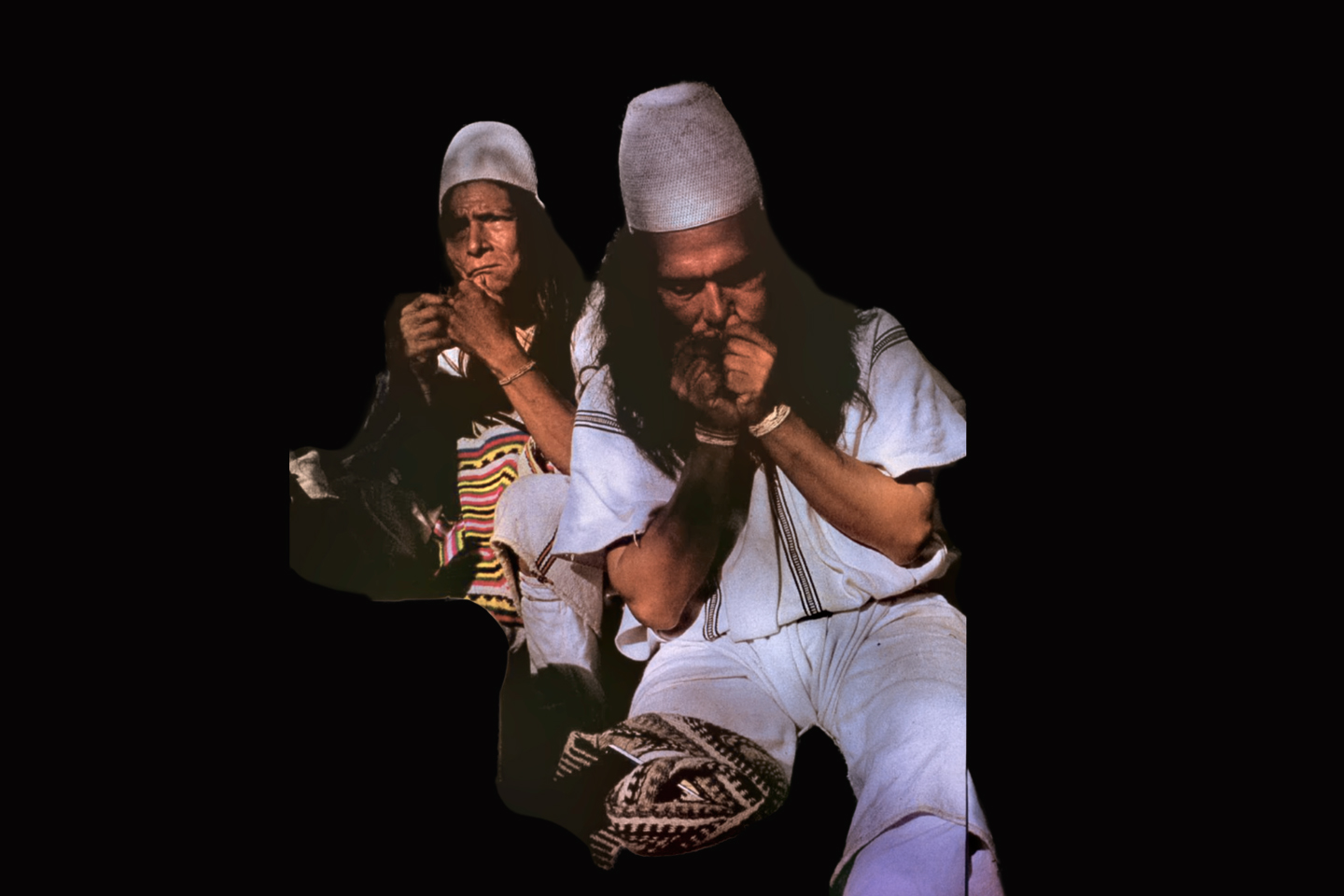

Years later, for better or worse, things have loosened up quite a bit as the Arhuaco have become more assimilated in the broader world economy. These days, it’s easy to find tribal members willing to have their picture taken (in exchange for an appropriate fee), so a quick search on the Internet will turn up hundreds of examples, all in less than a second. This photo (below) accompanied an article put out by the BBC, a few years ago:

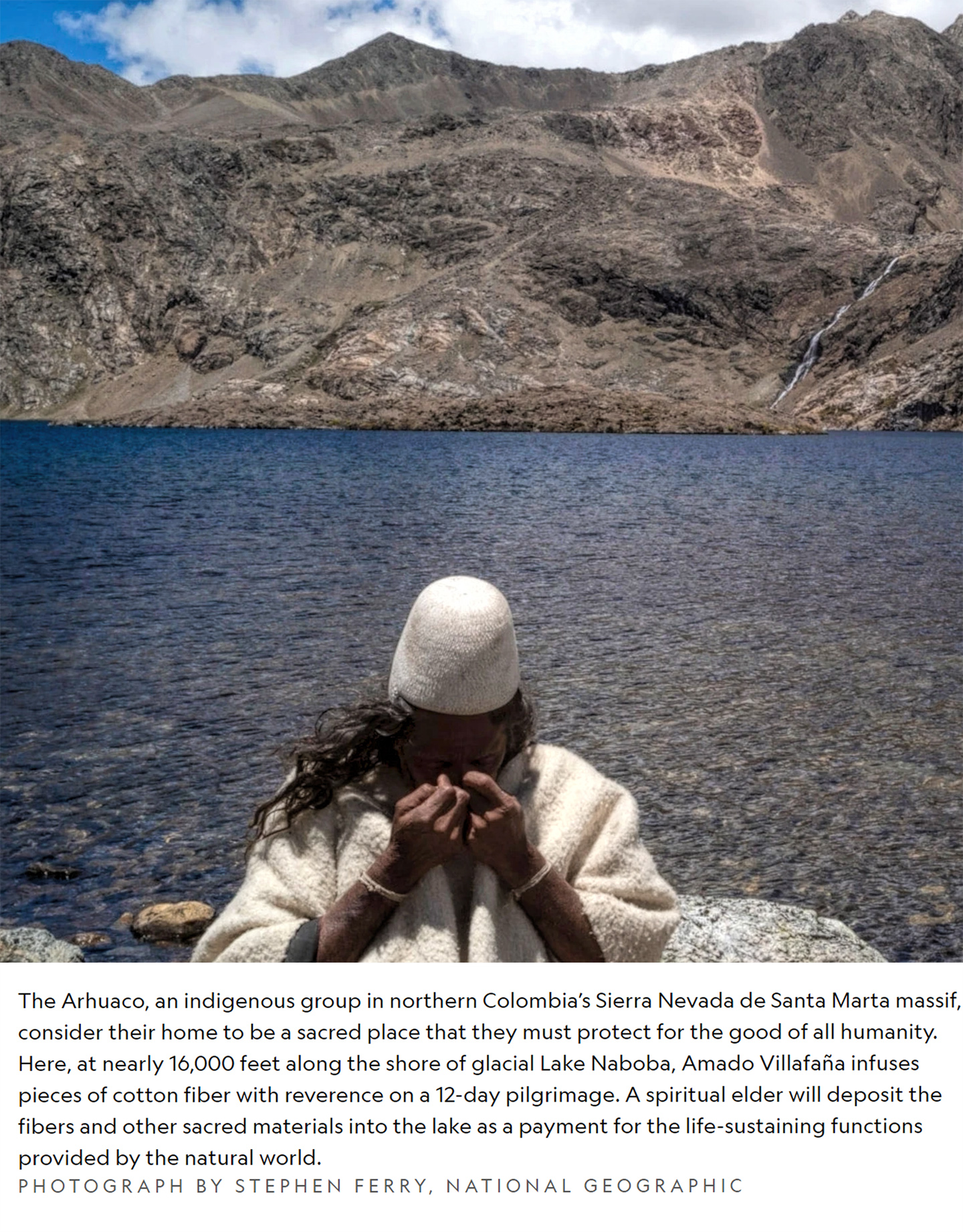

The men look much as I remember them, especially those unique white caps, and their long, dark hair. I chanced upon another article about the Arhuacos in a recent National Geographic. It was this next picture that really caught my eye:

According to the caption on the photo, this Arhuaco elder has his hands raised to his face, holding cotton fibers that he is infusing with reverence. It’s not an action that I personally observed, but as it turns out, that hands-to-face gesture is a form of meditation for the Arhuaco, and I found several additional references to it, with more photos.

Is there any possibility of a connection with those artifacts from Tumaco?

The images of the Arhuaco men were taken by National Geographic photographer Stephen Ferry, for an article that appeared in the magazine in October of 2004. The ceramic figurines were created by Tumaco artisans, nearly 2,000 years earlier.

The caps, the bracelets, and the hands to face gesture depicted on these ancient figurines are all strongly reminiscent of the traditional dress and meditation practices of the present day Arhuaco. There’s nothing definitive about that sort of evidence, but for me, personally, it was a Eureka moment.

The Arhuaco culture, and the Tairona culture with which they are allied goes back to at least the first century A.D., which is right about the time the Tumaco culture was at the peak of their development. Did a party of men from the Pacific Coast make their way to the Caribbean? Alternatively, did a group of Arhuaco or Tairona men travel up the Magdalena River and across the Andean cordilleras, ending up in Tumaco? Exploring, trading, possibly proselytizing, either group may have traveled into the other’s territory, and Tumaco artisans could have recorded the encounter, just as they recorded everything else, in the form of ceramic figurines.

Given the evidence, some form of contact between the two groups seems entirely probable. The Arhuaco and the other tribes of the Sierra Nevada are intensely spiritual people with a very old religion. To what extent was that religion influenced by contact with the Maya, who traded with the Tairona? With the Muisca, in central Colombia, who spoke a similar language? With the Tumacos…?

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

Disclaimer: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff, but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any map or photo to expand the images

If you’re interested in the Tumaco Culture, check out the rest of the series, beginning with Tumaco: Part 1: Atrocity Tops Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia. Next up: Tumaco: Part 5: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Tops Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

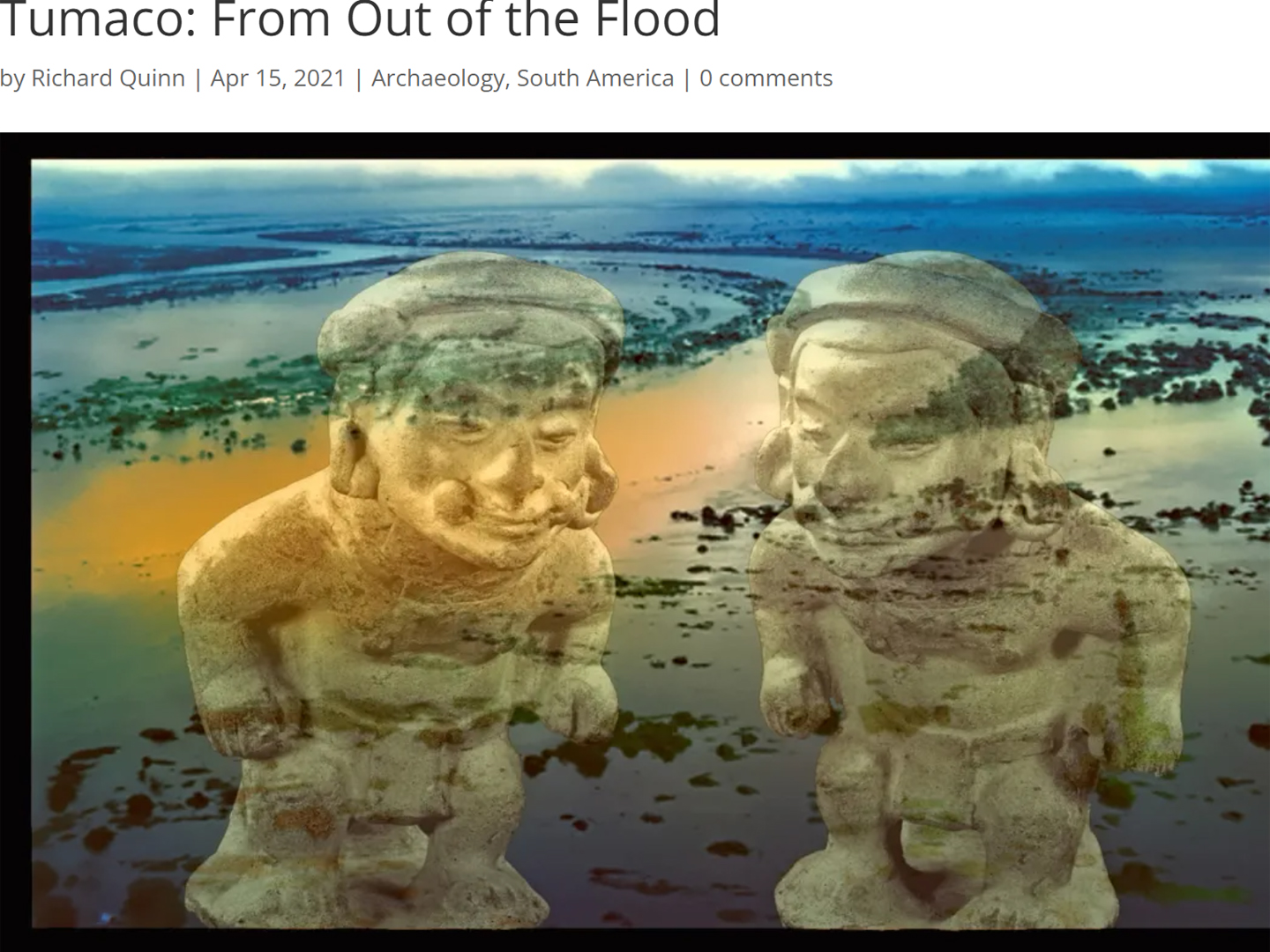

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

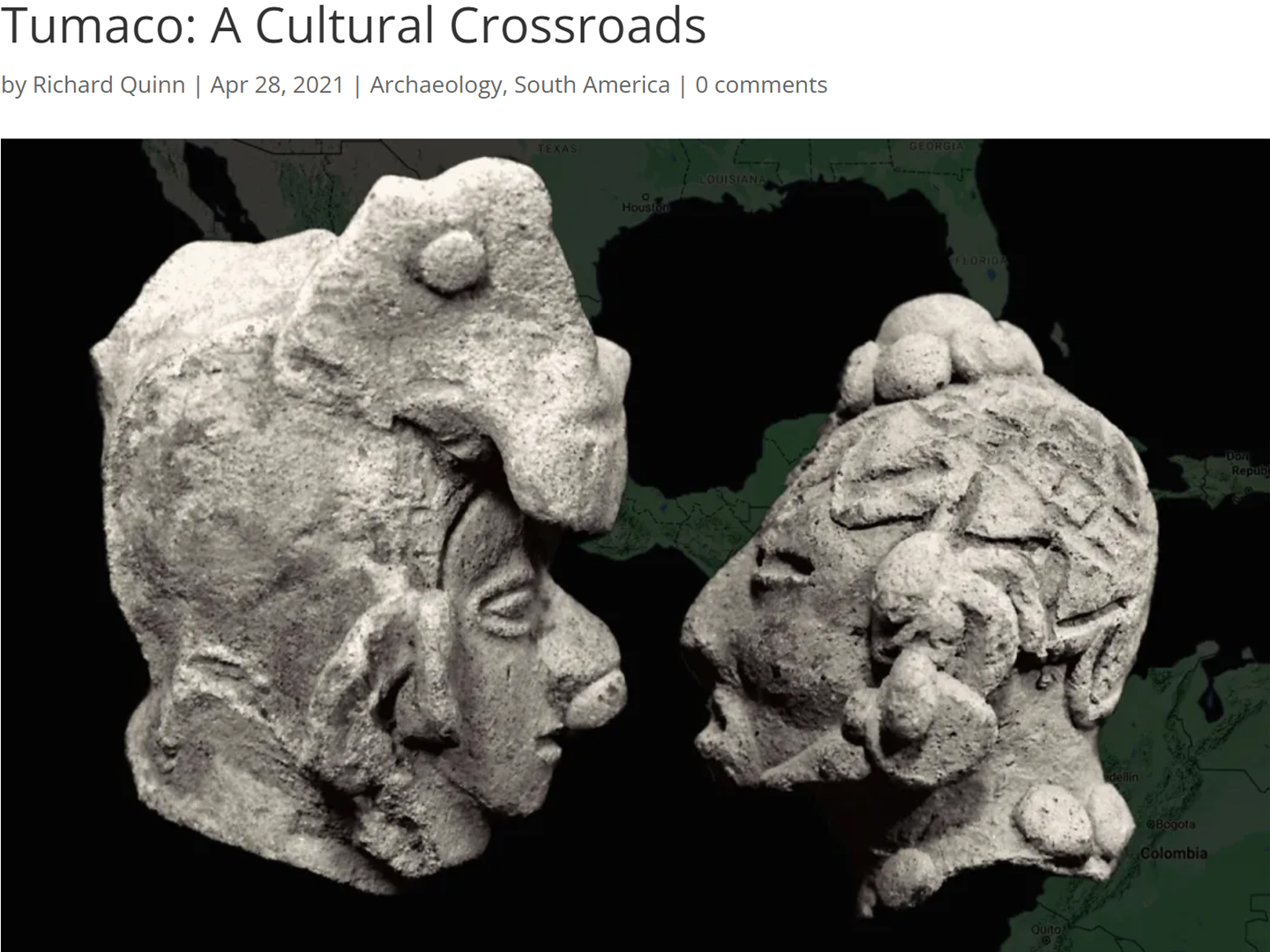

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments