The primary occupation of all early humans was the gathering of food. For most, it was a full time job, while others had it easier, but none of them ever advanced beyond the basics until they found a way to solve that basic problem, by creating a reliable, sustainable surplus large enough to feed the whole group. That single development allowed population growth, and the luxury of loftier pursuits.

In the area near Tumaco, on the Pacific Coast of Colombia, early attempts at growing crops were thwarted by the rivers that frequently overflowed their banks, and tides that surged inland, sometimes for miles, washing everything away. Over time, they came up with a system of raised fields flanked by drainage ditches that allowed them to channel the excess water, and with that, their basic problem was solved. The soil of the alluvial plain was exceptionally rich, so their harvests were exceptionally abundant. Since they no longer had to expend all their energy finding their next meal, a social structure evolved, along with an intricate system of beliefs. The end result was a ‘civilized’ way of life that was quite sophisticated, and unique to this small part of the ancient world, beginning more than 2,000 years ago.

The ebb and flow of floodwaters dictated Tumaco agricultural techniques, as well as the layout of their towns and villages. Communal houses and temples were built atop earthen platforms to keep everything dry when the waters rose. It was important to keep the graves of their dead safe as well, so they constructed massive platforms for use as cemeteries, ensuring that everything they buried stayed buried, well above the high water mark. Unlike many of their contemporaries, they did not build with stone. Their houses and temples were made of wood and thatch, materials that don’t survive the passage of time, so the only structures of any kind still remaining are the platforms, worn by the millennia into mounds that look like natural hills.

All of the mounds, but especially the tolas, the burial mounds, were loaded with archaeological remains. There were household items, stone tools, pottery of various types, and then, there was gold! Personal jewelry, like nose rings and ear rings, and finely wrought ceremonial objects, some of the finest gold work in the ancient Americas. Once the word got out, legions of tomb robbers descended, and the real archaeologists were outnumbered, a hundred to one. For every Tumaco archaeological site that has been properly, scientifically excavated, there are at least a hundred more that were destroyed by looters looking for gold, and for every guaquero that found it, there were at least a hundred more that did not. What they encountered instead were artifacts made of clay, odd little figurines depicting people, their daily lives, their infirmities, their heroes, as well as the beasts and demons of their elaborate mythology. Figurines and other artifacts unearthed by the scientists ended up in museums, while the finest, most elaborate pieces, which were almost invariably found by the looters, ended up in private collections. Either way, it is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

For any artifact to have scientific value, you have to know the context, how, when, and where it was found; the nature of the site, what else was found with it; the stratigraphic sequence; anything that could be used to facilitate dating. Pieces offered for sale by antiquities dealers rarely have any of that, because the guaqueros who supply the market lack even the most rudimentary scientific expertise. For them, a good job is when they manage to dig something up without breaking it. Worse: most diggers are deliberately evasive about how and where their treasures were found, because they don’t want to give away the location of a good source! Without the context of its origins, an artifact is reduced to mere art, without the fact, but what’s done is done, and, with few exceptions, the Tumaco art is all that remains.

Note: the artifacts featured in these photographs were not from a single source. They represent an assortment of stylistic phases, and were originally recovered from an unknown number of different sectors in the region once occupied by the Tumacos. The one thing they do have in common: all of them were available for purchase in Bogotá, back in the early 1970’s.

FIGURINES:

Most of the figurines that have been recovered in the Tumaco area are broken; in many cases, they appear to have been deliberately smashed before they were buried, possibly in ritual sacrifice. Even the relatively complete examples are usually cracked or missing limbs, but they still provide a quite wonderful sense of the artistry that went into their manufacture.

A typical Tumaco figurine is made from fine-grained greyish clay, deposits of which have been found near the banks of area rivers. Pieces were produced using press-molds (see previous post), then finished by hand, fired, and painted. In some cases traces of the original pigment remain, but most Tumaco artifacts are plain gray, worn smooth by their lengthy burial in swampy ground.

That brings to mind a trick one of the antiquities dealers in Cali showed me, a test that he used to spot counterfeit copies of Tumaco figurines. He’d lick the back of the head, just one good lick, and he’d watch to see how long it took for the surface to absorb the moisture. If the wet spot disappeared quickly, the clay was too porous, and the piece wasn’t really old. If the wetness was absorbed slowly, he’d put the wet spot under his nose, and he’d inhale deeply. If it exuded an odor like moldering potting soil, that meant the clay was infused with the essence of the burial mound, and the artifact was probably real.

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen:

The simplest figurines are small, solid, and only finished on one side, like these two (above), both about 10 cm in height.

Other, more sophisticated figurines are also made with molds, but they are hollow. The earliest examples are relatively thick-walled, and not at all delicate. The hollow figurines will always have a good-sized hole poked into them somewhere, an air vent, so that they don’t explode when they’re fired.

Often, it’s in the belly, where a navel would be, as is the case with this figurine of a Tumaco chief (above).

With others, like this figurine of a seated woman (above), the vent is concealed on the flat bottom of the piece.

The woman’s head exhibits the swept back cranial deformation that was common among a number of different cultures in the New World, including the Maya–but if figurines such as this are a reliable indicator, the bizarre practice seems to have reached its peak with the Tumacos. They would bind the heads of infants during their early growth years, in order to permanently distort the shape of the child’s skull. The resulting flattened, exaggerated forehead was considered beautiful, and served as an unmistakable symbol of elevated social status; a peculiar distinction that was reserved for the elite, and for their favored offspring.

Tumaco ceramic art is remarkably sophisticated, utilizing a number of techniques that are considered quite advanced, but we can’t give them all the credit for any of it. The coastal regions of the ancient Americas were occupied by a lineage of increasingly developed populations, beginning thousands of years before the advent of the Tumacos, and there is evidence of wide-ranging trade, in ideas as well as in goods.

One group that was a contemporary of the Tumacos was the Jama-Coaque, people who lived very similar lives, but in the area just south of the Tumaco territory. Those ancients also produced figurines, using the same essential techniques, but the artifacts recovered from Jama-Coaque burials differ from their Tumaco counterparts in several ways. Most notably, they used a different type of clay, more of a beige color, rather than gray, and very fine grained.

The molded details on Jama-Coaque pieces tend to be more sharply defined, and the original pigment seemed to adhere a bit better, so more of it has survived, as evidenced on the back side of this figurine of a standing woman (above).

Cranial deformation was practiced, and is depicted in Jama-Coaque figurines, but it is somewhat less pronounced (above).

And then, there are the eyes: on most Tumaco human figurines, the eyes have a natural, ovoid shape, while Jama-Coaque pieces tend to be more rigidly stylized, with eyes shaped like a sideways letter D.

Such differences may seem minor, but they reflect important societal distinctions, and there is also the question of patrimony. Most Tumaco artifacts are from Colombia (the exception being pieces from the La Tolita sites in Ecuador), while ALL Jama-Coaque artifacts are from Ecuador. The laws prohibiting the trafficking of artifacts were enacted much sooner in Ecuador, so any Jama-Coaque (or La Tolita) pieces sold by Colombian antiquities dealers during the heyday of that trade were already black market, smuggled across the border from Esmeraldas.

This next piece is an excellent example of an artistic format that was developed elsewhere, and subsequently adopted by The Tumacos for their own purposes. The double spout and bridge vessel is a traditional design in many parts of Peru; originally used to store drinking water, these vessels later developed into portrait jars, featuring stylized depictions of human faces, animals, and activities, ranging from warfare to graphic sex.

In this example (above), the Tumacos have grafted their own unique motifs onto the traditional form, creating a seated gentleman with a modestly swept back skull, a fitted cap, sagging cheeks that indicate age, and studs on either side of his nose, all typical features of Tumaco artifacts. This piece is hollow, 15.5 cm in height, and in unusually good condition.

This last example is a complete figurine that represents the pinnacle of Tumaco artistry. The piece is 19 cm in height, and is masterfully executed in three dimensions.

The man is clearly in motion, a Bearer carrying a load in a pack on his back. He’s dressed in a loin cloth, and has big ear spools in distended lobes. The face is particularly expressive with significant detail, including a large, hooked nose, prominent eyebrows, and cheeks bulging with coca, a stimulant that has been used throughout the region for thousands of years.

The support attached to the back of the piece forms a tripod with the two legs, allowing the figurine to stand upright and remain stable; the finished sculpture was clearly intended for display. When this piece was found, the head had separated from the body, and was reattached, as can be seen in the side view (above).

The Bearer was quite likely a real character. The Tumacos, who lived on the coast, traded with people living high in the Andes. There were no roads, and they had no draft animals, so high value trade goods traveled up and down steep trails on the backs of men just like this guy, fortified for the rigors of the climb with a double helping of his favorite chew!

ALL HEADS, NO TAILS

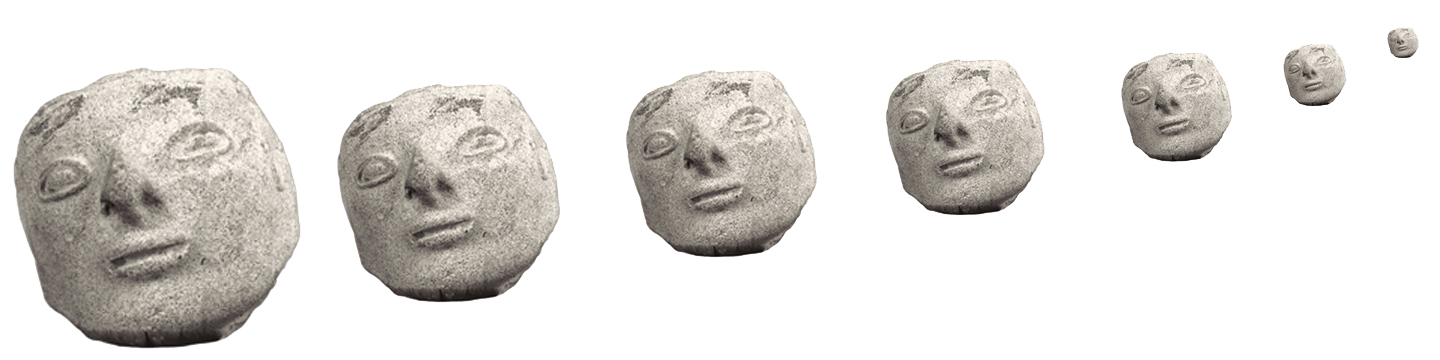

Complete figurines from the Tumaco area are rare. A typical artifact is more likely to be a fragment, sometimes nothing more than a face, like a ghost from a distant past.

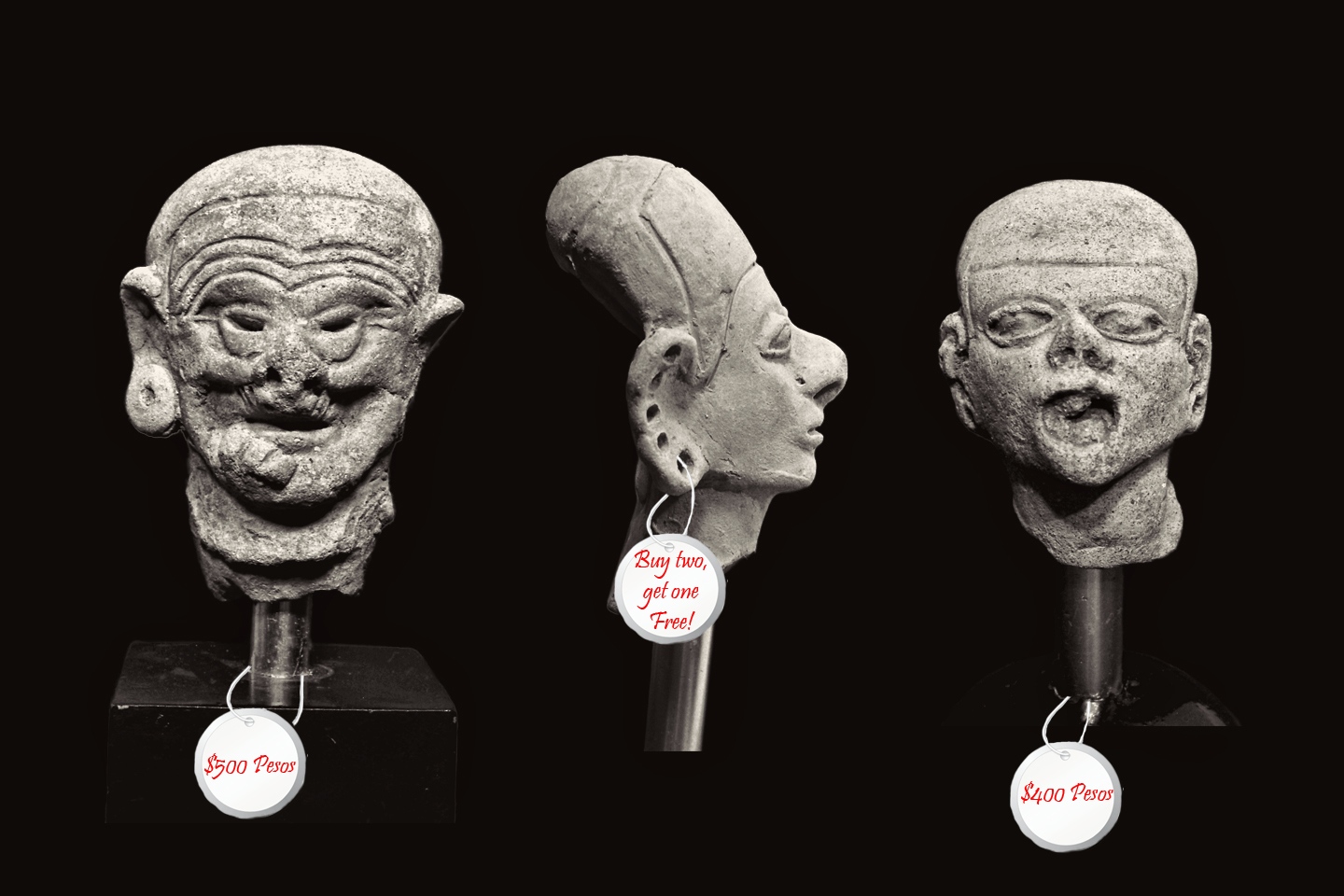

The segments of the figurines of greatest interest to the guaqueros were the heads, because they had value, even when the rest of the piece was hopelessly damaged. “Tumaco Heads,” usually mounted on a small stand, were among the most common items offered for sale in Colombia’s legal antiquities shops, and because each one was unique, customers would often buy several, bartering for a better price, like any common souvenir.

Since there were no restrictions on the export of antiquities, the cultural heritage of the Tumacos poured out of Colombia, packed in the luggage of tens of thousands of tourists, and was scattered all over the globe, so much of it that even today, half a century later, you can pick up an ‘authentic Tumaco Head’ on eBay, any time you like. If you look hard enough, you might even find one at a garage sale.

PORTRAITS IN CLAY

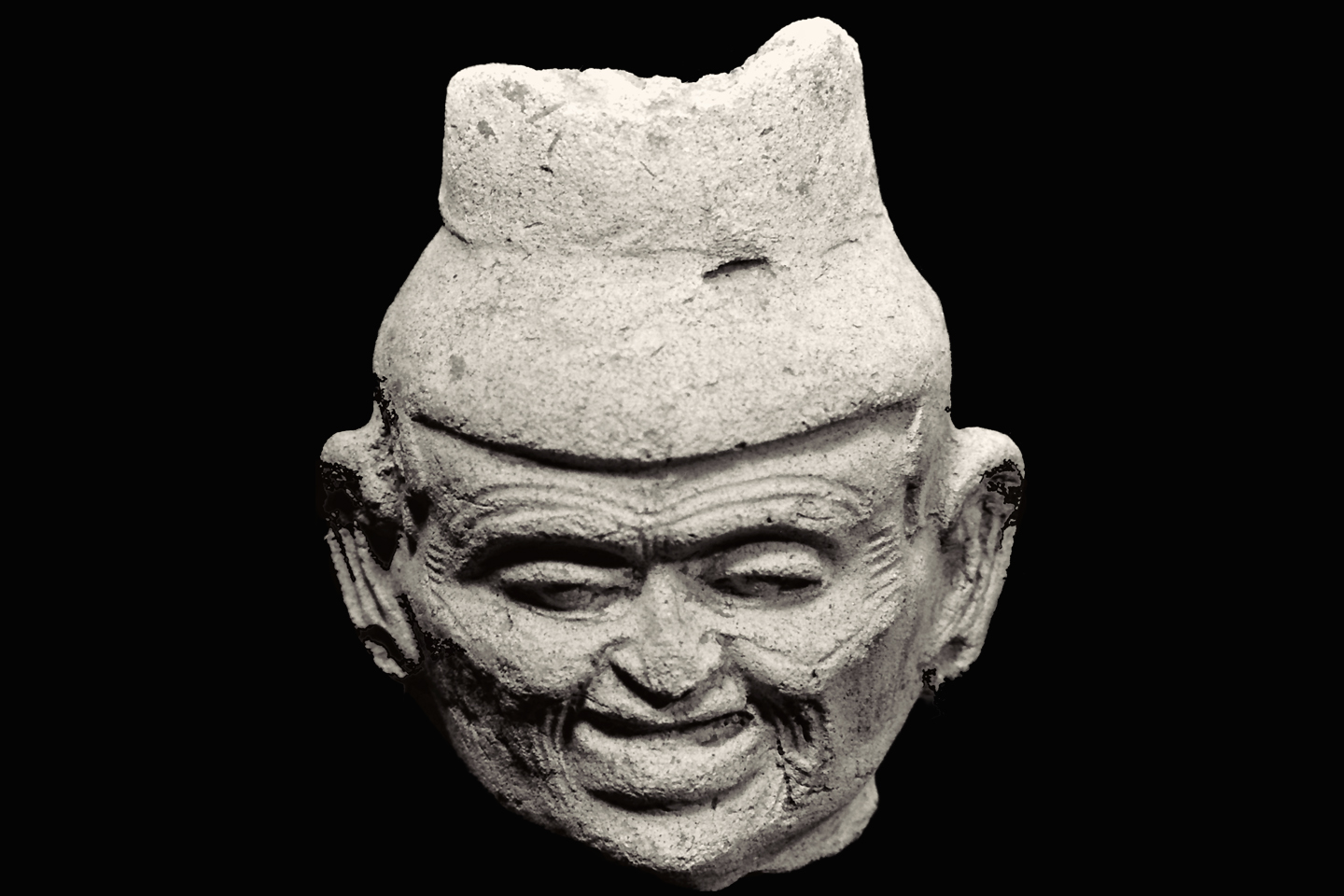

Typical “Tumaco Heads” share a great many similarities: cranial deformation, a fitted cap, ovoid eyes, but there’s probably more to be learned from the differences between them. In the example on the left (above), the figure has a stud on either side of his nose, as well as a labret–a lip plug–and dimples along the edges of the ears indicating multiple piercings for ear rings. Such jewelry was made of gold in the real world of the Tumacos, and was a mark of social status. The head on the right is missing most of those features. We can make assumptions, that perhaps the figurines represent individuals of a higher and lower caste; but we would only be guessing.

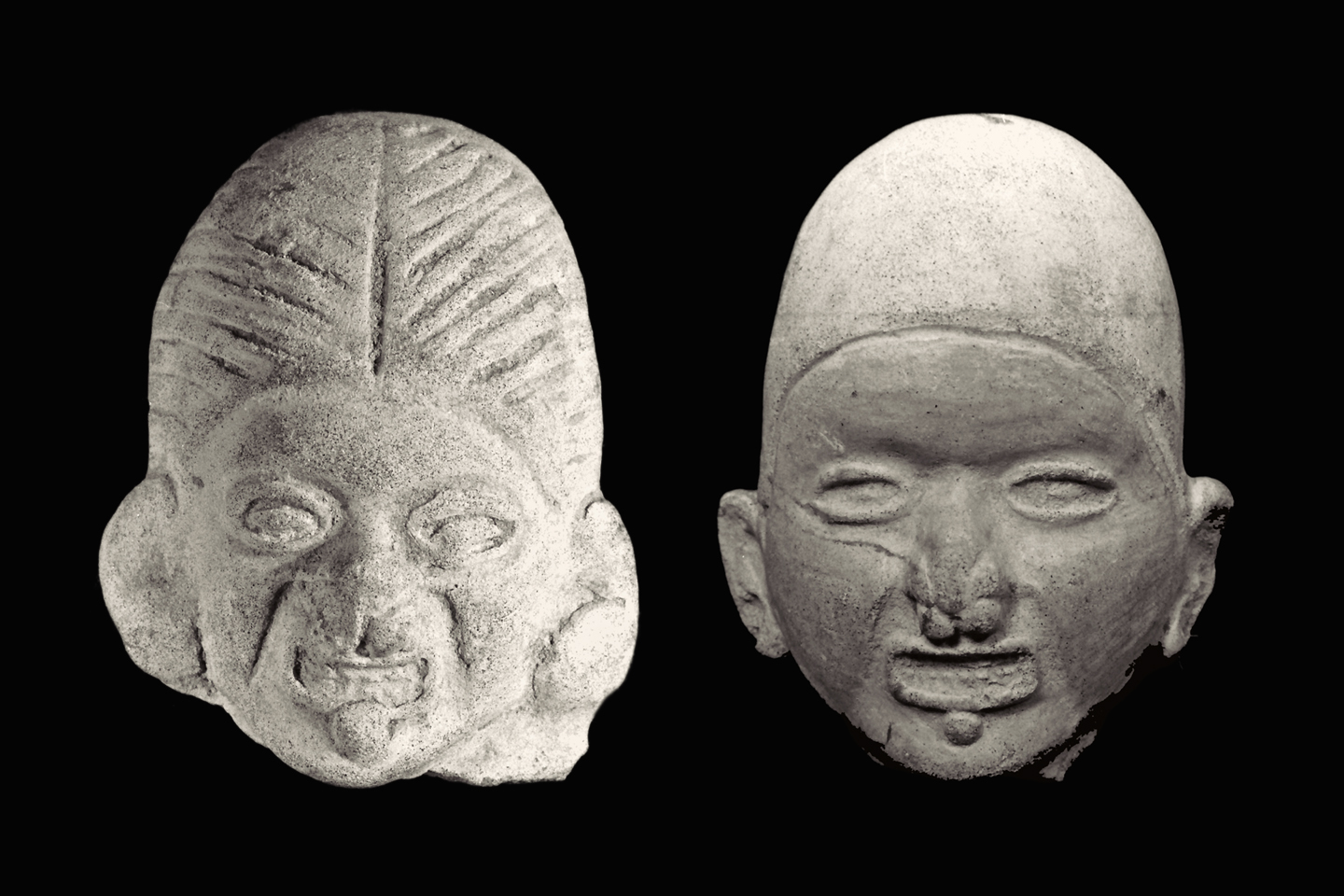

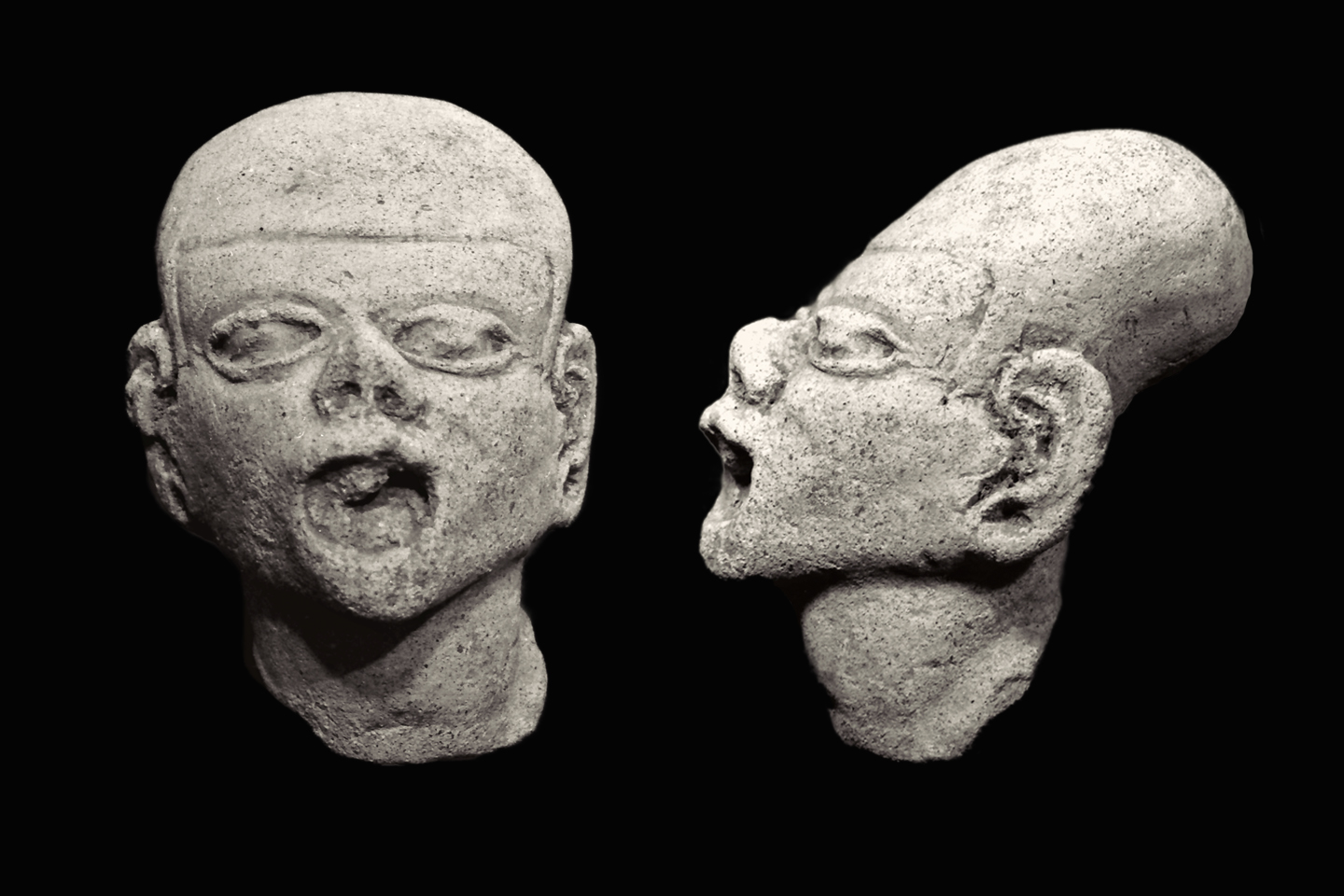

These two pieces (above) share a great many similarities, from the jewelry depicted to the strange rectangular grimace and the display of clenched teeth, but, once again, the differences are of greater significance. The head on the left is missing the traditional cap, instead showing a full head of hair with a part down the middle. Even more important is the manufacturing technique. Both pieces were molded, but the head on the left is solid, while the example on the right is hollow, far more delicate, with a smoother, more finished appearance. We have the same essential theme—the grimacing man—done by different artists, using different techniques. The two pieces clearly represent different phases of the Tumaco culture and are probably separated by hundreds of years, but in the absence of proper excavations, we can’t apply accurate dates to any of these pieces. Whatever the purpose of the figurines, they evolved over time, and the Tumaco artisans got better and better at making them.

We do know that the figurines were decorated in various ways. They were painted, as evidenced by the traces of original pigment that often remains, and they were sometimes adorned with gold rings. The holes pierced through the edges of the ears on the head pictured above would have served that purpose, as would the hole pierced through the nose on the head pictured below.

The example above has other features worthy of note. The head is finished in all three dimensions, and the face is much more natural, as if modeled from a real person. The nose is quite pronounced, and the left cheek is bulging with a quid of coca leaves, a common feature on Tumaco figurines.

This fragment (above) is clearly a portrait of an individual: a portly gentleman with a pendulous belly, and both cheeks bulging with coca.

Two views of the head of the “Bearer carrying a load” figurine from the previous section, emphasizing the bulging cheeks.

OLD AGE AND DISEASE:

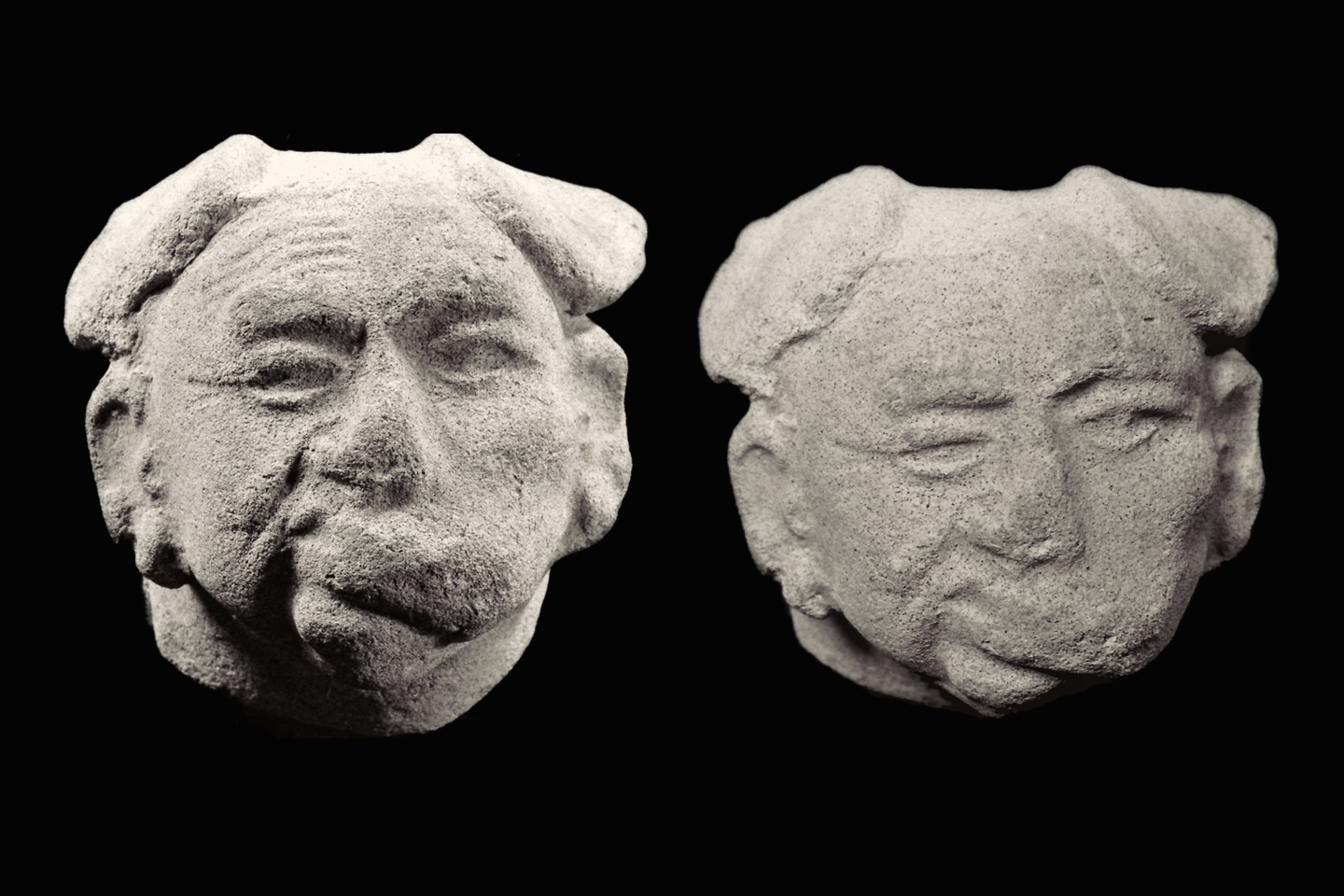

Based on studies of skeletal remains, the median lifespan of Tumaco men was only about 35 years. Clearly, there were exceptions to that rule, as evidenced by the abundance of figurines depicting age. Above is a trio of old men, with deep lines on their foreheads and crow’s feet alongside baggy eyes. The piece on the left is exceptionally expressive, like a true portrait, as is the piece in the center (more on that one below). The head on the right is primitive, more of a caricature. Is the piece on the right from an earlier phase of the culture? Probably, but because these heads were excavated and trafficked by looters, they can’t be accurately dated.

Two more old men from Tumaco. The head on the left is missing most of his teeth, but only the front teeth, as if from an accident. The old gentleman on the right is missing ALL of his teeth, as evidenced by deeply sunken cheeks, and in his case, it’s almost certainly a consequence of age.

Another common element among Tumaco figurines is the depiction of infirmities. The example above shows a man with a growth in his mouth, while the example below shows a man with some sort of tumor, or a goiter, distorting the shape of his face.

Finally, two more views of the elder in the middle (from the “trio of old men,” above). Furrowed brow, sunken cheeks, baggy eyes, and much of his nose is missing. It may have broken off, or it may have been sculpted that way to represent a disfiguring disease; the latter theory is bolstered by the large growth below the man’s lip.

Some have theorized that the figurines depicting diseases were used in ceremonies that ended with the smashing of the figurine, one way of explaining the fact that so many were broken before they were buried. Transference of a malady from a suffering human to a symbolic object is known to occur in some shamanistic rituals, so that’s certainly a possibility.

LARGE SCALE SCULPTURES

Most Tumaco figurines are of similar size, ranging from 10 cm to around 20 cm in height, but there is a sub-class of clay sculptures that are significantly larger. In this example (above), the head alone measures 14 cm, and the sculpture from which it was broken, if it was still intact, would have been at least 50 cm tall, more than double the normal height.

he large head, pictured side by side with a fragment of the more typical size. The large head is hollow, made of coarse reddish-brown clay. The shell is thick, so the piece is relatively heavy. The head was represented as being from Tumaco, but the composition of the reddish clay would seem to indicate an origin further south.

When archaeological sites are destroyed by looters, and the artifacts are scattered by traders, the world suffers an irrecoverable loss. In the case of the Tumacos, that loss is enormous.

~~~~~

Disclaimer: I am not an academic. The assumptions made and the conclusions drawn in these posts are those of a reasonably well-informed enthusiast; I haven’t put in the work that might make me an expert. At one time, I was up to my neck in this stuff, but the most that entitles me to is an opinion.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen:

If you’re interested in the Tumaco Culture, check back to read the rest of the series. beginning with Tumaco: Part 1: Atrocity Tops Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia. Next up: Tumaco: Part 3: Cultural Crossroads

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

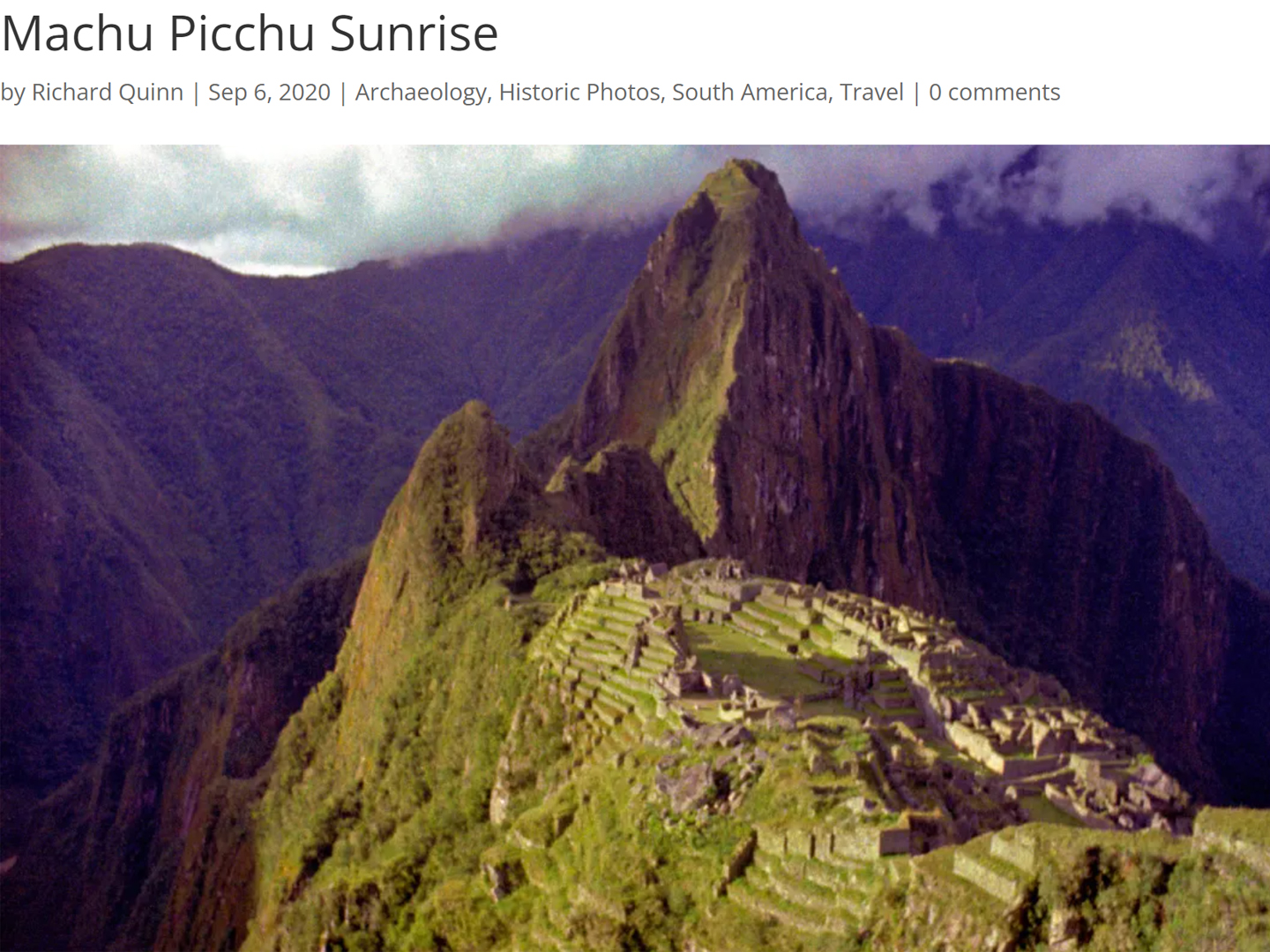

South America Before the Conquistadores

Tumaco: Atrocity Tops Antiquity on the Coast of Colombia

Within a matter of a few years, every readily accessible site had been looted and stripped of artifacts. There were laws in Ecuador prohibiting trade in antiquities, but during the 1970’s, there was no such law in Colombia, so the Tumaco heritage, extraordinary in its complexity, was scattered to the four winds.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

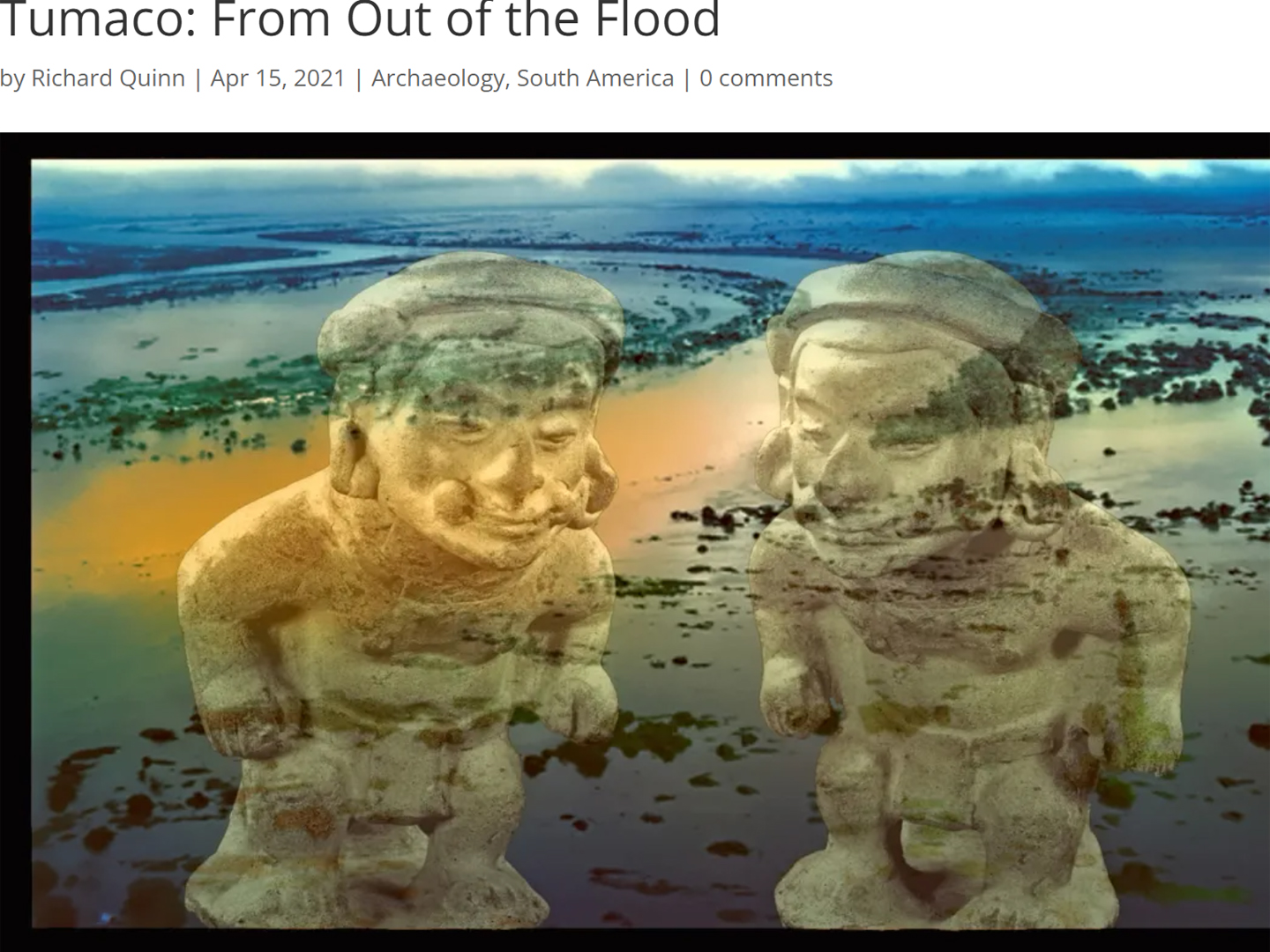

Tumaco: From Out of the Flood

Far more common than the precious metal were the artifacts made of clay, small, often elaborate figurines depicting nearly every aspect of the people’s daily lives, as well as their animistic mythology. It is through those figurines, some intact, but most in fragments, that these all but forgotten people have come to be known.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tumaco: A Cultural Crossroads

Traders coming down from the north had to endure many days of difficult travel along a coast that’s tough to negotiate even today. The reward must have been worth the trouble, because men from the Yucatan did, in fact, make that journey, trading goods, as well as ideas with the men of Tumaco.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

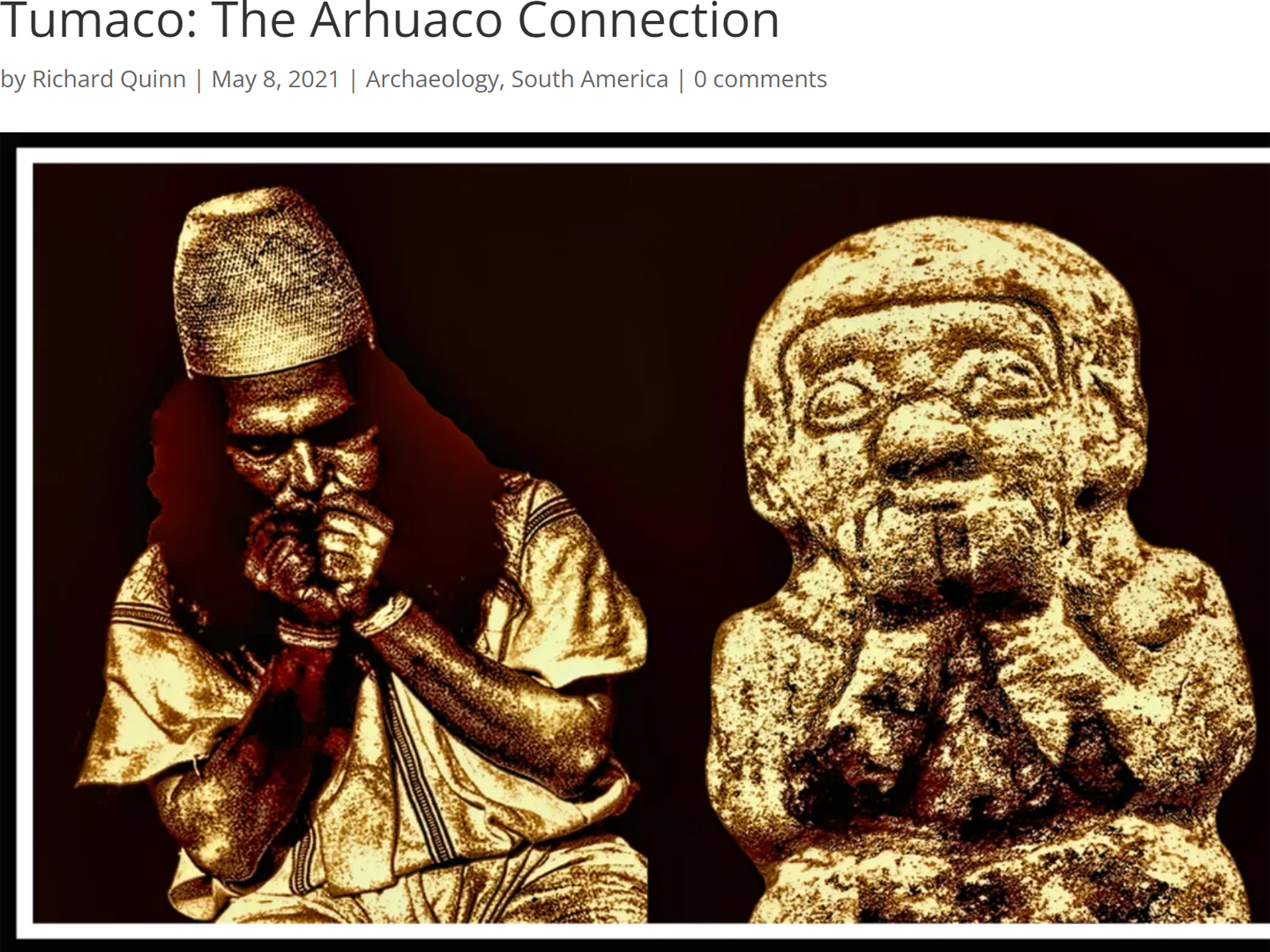

Tumaco: The Arhuaco Connection

What we really know of history is like an ancient tapestry, worn, and threadbare, with missing patches confusing the grand design. When we make a new connection, we restore a missing thread, and little by little, thread by thread, we fill in those troublesome blanks.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

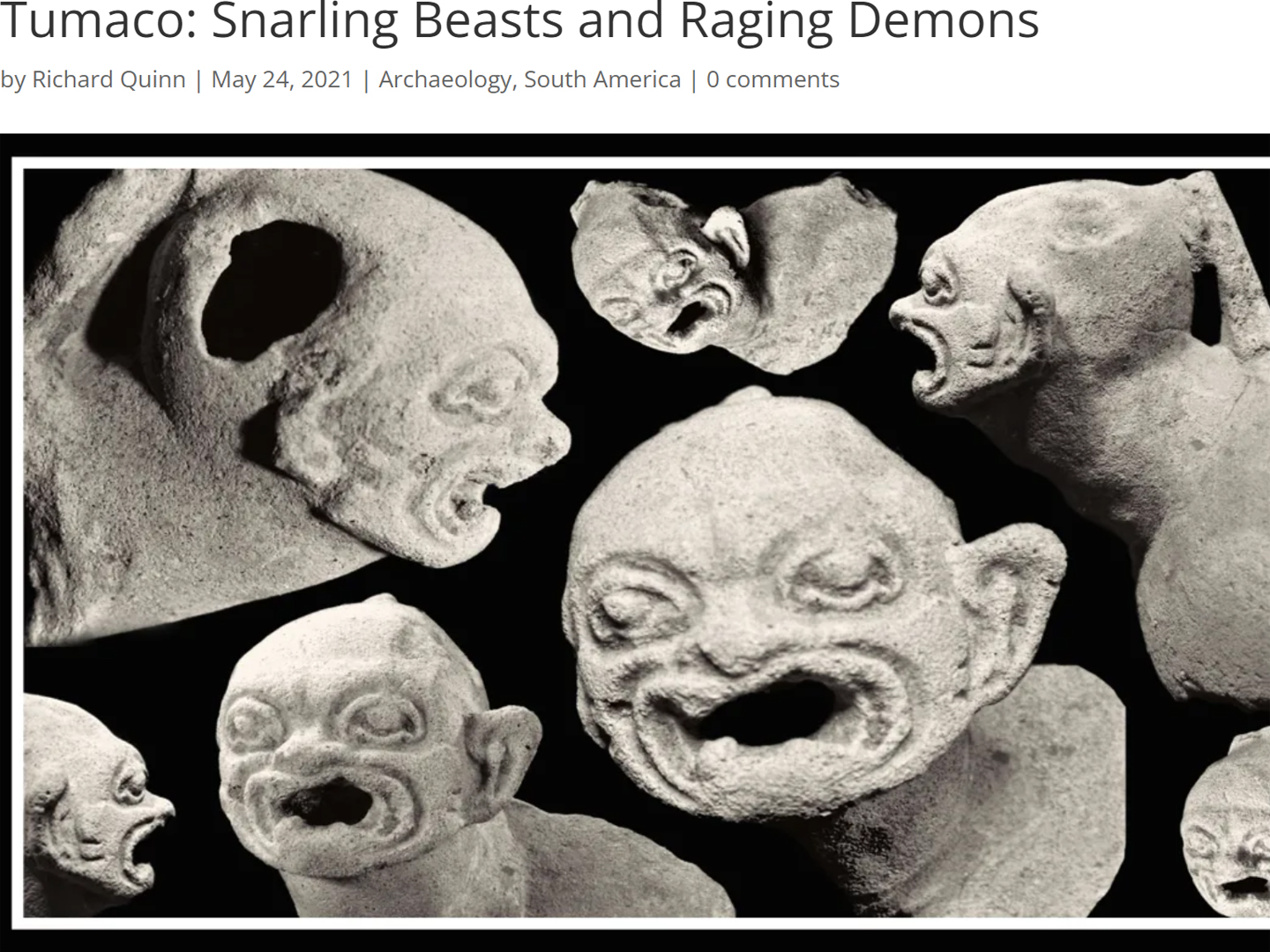

Tumaco: Snarling Beasts and Raging Demons

There was so much ancient pottery in the Tumaco area that it literally washed up out of the ground after every big rain. With so many men out there looking for gold, it was impossible NOT to find Tumacan ceramics. Strange figurines and fragmented sculptures, unlike anything that had been found before, anywhere else in Colombia.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments