Arizona didn’t become a state until 1912, the last of the contiguous 48 states to get the upgrade from U.S. Territory to full statehood. Prior to that time, which wasn’t so very long ago, it was still the Wild West, complete with real cowboys and renegade Apaches, a rugged land of untamed forests, canyons and deserts.

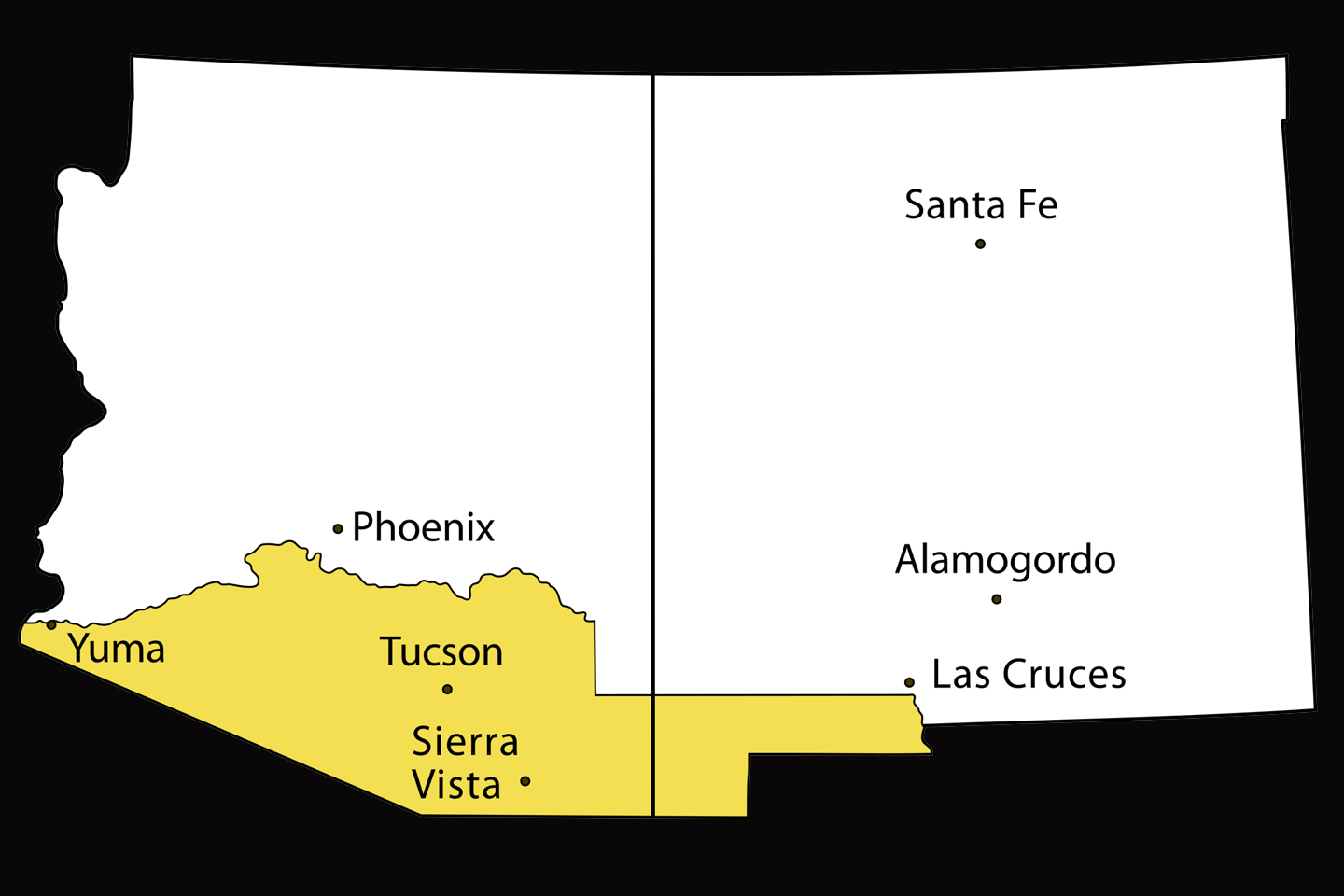

The arid region in the southern part of the state, including the area around Tucson, was formerly a province in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the vast Spanish colony in what is now Central America and Mexico. When Mexico won their independence in 1821, ownership of the province passed to the newly formed Republic, but that wasn’t quite the end of it. Thirty years later, the United States needed a large swath of land for a southern railroad right-of-way. In 1853, the cash-strapped Mexican government was pressured into selling 30,000 square miles of hot desert for a cool ten million bucks, in a politically charged transaction known as the Gadsden Purchase. (That equates to $240 million in today’s money, but that’s still what you’d call dirt cheap.)

The Gadsden Purchase of 1853

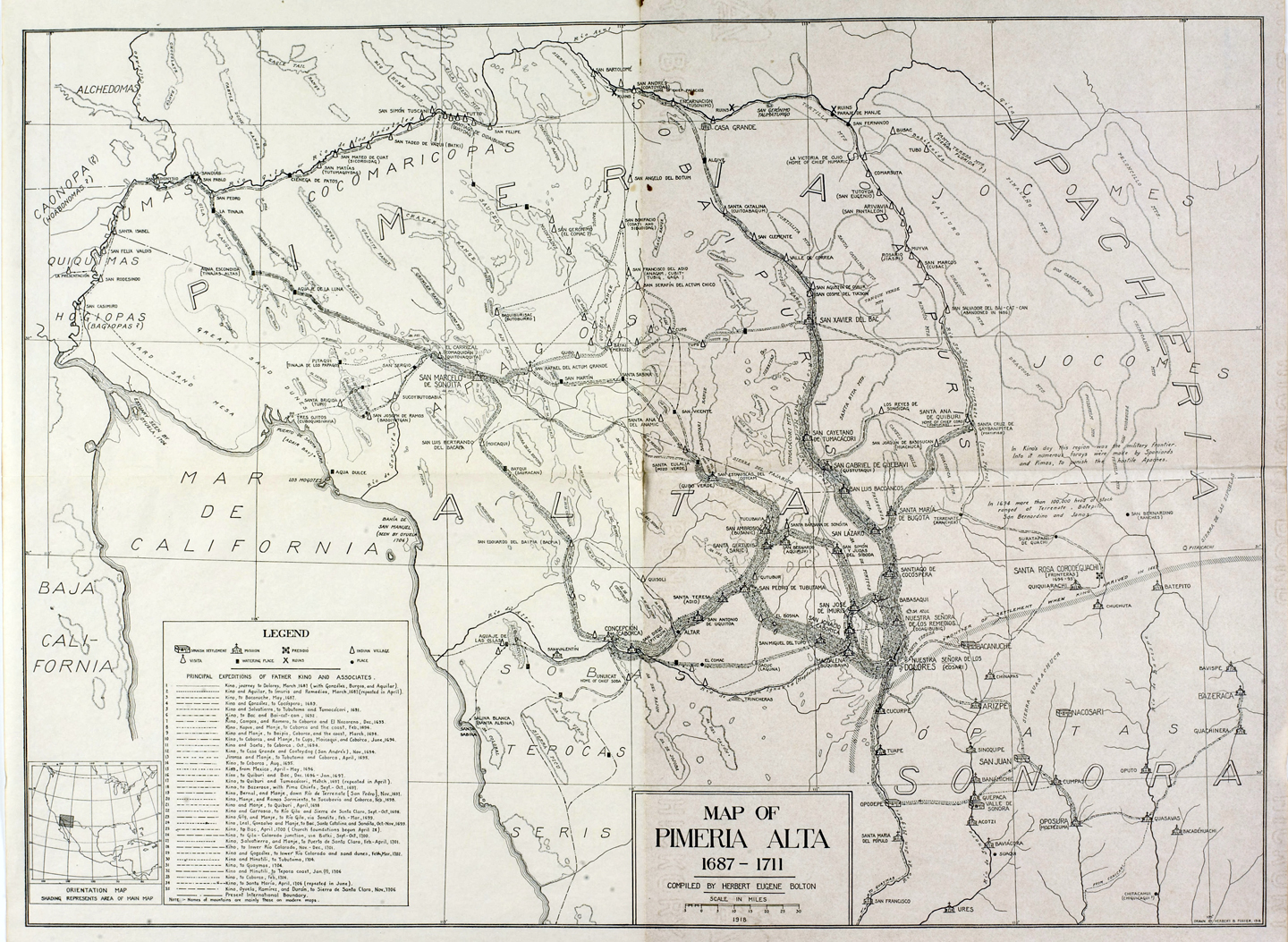

None of that was really anything more than some re-drawn lines on a map, and an altered set of place names. The thing is, Spain, and by extension, the Republic of Mexico, never actually owned that desert in the first place. At most, they were occupiers, not really in control of this territory, formerly known as the Pimeria Alta. The whole region belonged to the Tohono O’odham, the Desert People, and in reality it was controlled by their enemies, the Apache, who raided both native and Spanish settlements with equal enthusiasm.

Spanish Colonies were created by Spanish cavalry, who easily quashed most native resistance with their superior weaponry and their shockingly brutal military tactics. The real trick was in holding on to the territory after the main force of soldiers moved on, so the second wave was always the missionaries, whose goal was to convert and domesticate the local population. These methods were largely successful with the O’odham, an agricultural people who adapted, albeit reluctantly to life in the Spanish Mission communities. As for the Apaches, they saw no reason to change a thing. They were nomads who were accustomed to simply taking whatever they needed from their more sedentary neighbors. For the Apache, such raids were neither a good thing, nor a bad thing; their strength as warriors made it their right. The Spanish missions were such easy pickings, their lives were better than ever, and in a very real sense, they were still in charge.

Father Kino

Father Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit, wasn’t the first Spanish missionary in the Pimeria Alta, but he was definitely the most successful. He first arrived in the area in 1687, and spent the next 24 years there, until his death in 1711. During those years, he established 24 missions, and dedicated himself to improving the lives of the native people, and preventing, or at least minimizing their exploitation by his countrymen. One of his missions was established near an existing O’odham community on the banks of the Santa Cruz River.

The mission church was built in 1700, and served the community until 1770, when it was razed to the ground during an Apache raid. The Padres and their O’odham flock responded by constructing a new church, some two miles away from the original. That church, built between 1783 and 1797, is still there today, and still very much in use by the local community.

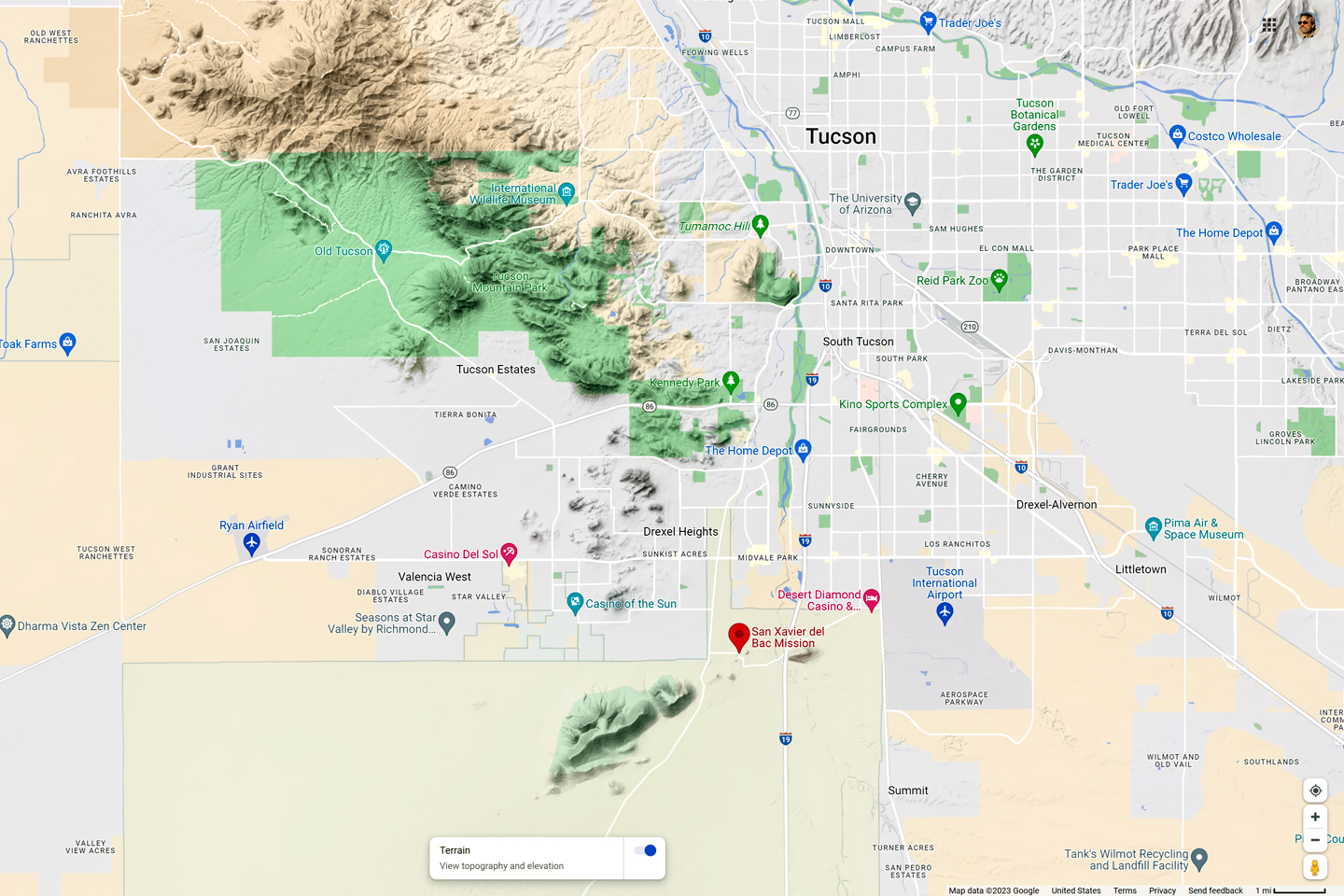

That church is the Mission San Xavier del Bac, the White Dove of the Desert, the finest example of Spanish colonial architecture still standing in the United States.

The mission of San Xavier del Bac, just minutes from downtown Tucson

Click Maps and Photos for an expanded view

Spanish Colonial Architecture

The term “Spanish Colonial Architecture” applies to a broad range of architectural embellishments. It refers to brick and adobe buildings coated with stucco, featuring a suite of common decorative elements, including (but not limited to) balustrades, moldings, cornices, arches, iron balconies, red tile roofs, and the occasional dome. Churches, public buildings, and fine homes dating from the 17th to the 19th centuries, when located in the cities and towns of Spain’s former colonies in the New World, are Spanish Colonial by definition.

When the Spaniards conquered a new territory, the first thing they built was usually the church. They put it on high ground, ideally on the site of an existing native shrine or temple, and they built it tall, with soaring towers intended to inspire awe, and to draw all eyes upward toward the heavens.

The Cat and Mouse façade above the main doorway at San Xavier del Bac

San Xavier has all of the traditional elements of a Spanish Colonial church, along with many others that are quite unique. The craftsmanship of the original building is superb, and features many fascinating details.

On either side of the molded façade above the main doorway to the church, you’ll see a cat toying with a mouse. Legend has it that if those cats ever catch those mice, it will signal the end of the world.

And then there are the towers, meant to be the highest point of the church, each topped with a cross. The first thing people notice about San Xavier del Bac is the fact that one of those towers is unfinished. It doesn’t have a top, much less a cross. That gaping flaw in the otherwise perfect symmetry is a large part of the building’s mystique.

According to one local legend, lightning struck the top of the east tower, while another version says it was blown off by a tornado. A more prosaic explanation involves the tax man: they say that the taxes are lower on an unfinished building, so the last bit was purposely left undone. The true story is even simpler: the original builders ran out of money. They intended to finish at a later date, but the congregation seemed to prefer it this way, so they’ve left it as is, perfect, in its imperfection.

The east tower of the mission church at San Xavier del Bac has never been finished

The original mission church is more than 225 years old, and it has been repaired and renovated numerous times in the course of that history. The interior was fully restored in an intensive five year effort by an international team of conservators, whose work was completed in 1997. Painstaking work to fully restore the exterior was begun in 1999, and is ongoing.

The white dome above the chapel is a distinctive architectural element, hearkening back to the cathedrals of Europe. The underside is a painted ceiling featuring scenes from the Bible and intricate gilded patterns.

The dome above the chapel at San Xavier del Bac

The interior of the church is like a museum, filled with unique artwork representing saints and angels and other religious figures. The conservators and art historians on the restoration team thoroughly cleaned every bit of it, removing many layers of overpainting. The paintings and sculptures were then meticulously repaired, and restored to their true original condition.

One particularly noteworthy sculpture is a representation of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Native American saint in the Roman Catholic Church. Also known as Lilly of the Mohawks, she was beatified by Pope John Paul in 1980, and she is the patron saint of the environment and of aboriginal people. The simple wooden statue shows her standing, arms crossed and eyes closed in prayer, while holding a crucifix.

Visiting San Xavier del Bac

The easiest way to get to San Xavier del Bac is to follow Interstate 19, the main route between Tucson and the border city of Nogales. The mission is easily visible from the highway, just eight miles south of downtown, and can be accessed by exiting on San Xavier Road, and following the signs. The parking area for the mission is about a mile west of the freeway.

There is no charge for entering the mission grounds. (Contributions are always welcome, but they’re not required). When visiting, it’s important to remember that San Xavier del Bac is, first and foremost, a living Catholic church, a sacred place of worship for the local community, many of whom are Native Americans with very deep roots in this region. It’s perfectly fine to take photos of the church, both inside and out, but never when services are in progress, and you must respect the privacy of the worshipers at all times.

San Xavier del Bac photo gallery

The San Xavier del Bac Mission is a wonderful subject for photographers. During the summer monsoon season, in July and August, you’re all but guaranteed a sky filled with beautiful white clouds to serve as your backdrop. The lines of the Mission are timeless. Aim just a little higher to exclude the people and cars at ground level, and your picture could be from any era in the last 200 years. Black and white, and sepia tone filters can be highly effective treatments for this type of imagery.

Ongoing restoration efforts involve the use of scaffolding, which can spoil your otherwise perfect photos of the historic church. Proper restoration almost invariably requires reversal or removal of material used during earlier, less effective restoration efforts. They have to strip off cement plaster that should never have been used before repairing and refinishing with traditional lime plaster. This is a meticulous, time-consuming process, working brick by brick, so the scaffolding has become an unavoidable fixture at the mission. When the work is finished, the old walls will be better than new. In the meanwhile? Choose an angle of view and a composition that de-emphasizes the areas where the scaffolds are in place.

Scaffolding spoiling your photo? Take a walk.

It’s just short distance to a better point of view.

For anyone visiting Tucson, San Xavier del Bac is one of the “must-see” attractions. The oldest building in the Old Pueblo is arguably the most beautiful structure in the entire state, but there’s no rush. With any luck, once the restoration is complete, the White Dove of the Desert will live on for another 225 years. (As long as those cats never catch those mice!)

Click any photo in this post to expand the image to full screen.

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments