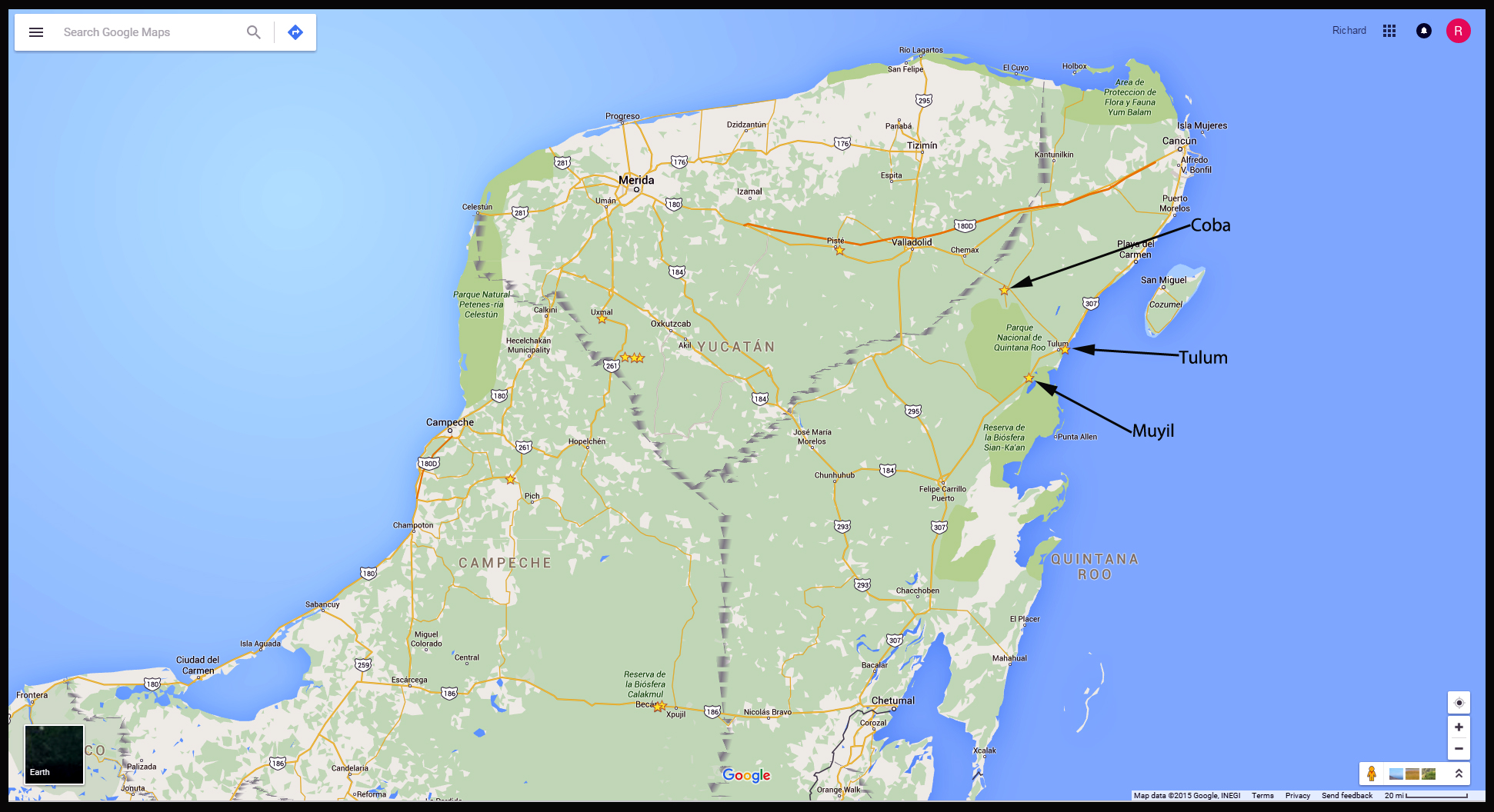

The historic range of the Maya was a vast expanse that encompassed fully a third of the land area of Mesoamerica: the entire Yucatan peninsula, much of the Mexican states of Chiapas and Tabasco, all of modern day Guatemala and Belize, and the western sections of Honduras and El Salvador. There are many hundreds of Mayan sites throughout this region, and while the large ones, like Palenque and Chichen Itza, are fairly well known to the world at large, the vast majority are obscure places that most people have never heard of. This post focuses on two of those more obscure Maya cities: Coba, the relatively large site that dominated the area around Tulum, as well as nearby Muyil, which, like Tulum, was subordinate to Coba. All three of these co-dependent sites are located quite close to one other, in the Mexican State of Quintana Roo, and all of them are easy to visit from Cancun.

Click for an expanded view

Today’s Yucatan consists of three Mexican Estados: Yucatan, Campeche, and Quintana Roo, where Cancun is located. Those are strictly modern-day political/jurisdictional divisions. The entire area is similar in terms of climate and geography, and the Maya made no distinctions along any of those arbitrary boundary lines: in their day, it was all one big happy homeland with, at its peak, close to two million inhabitants. Unlike the Aztecs and the Incas, the Maya were never unified under a single ruler, so their remarkable civilization was never a true empire. They were, instead, a hodge-podge of independent city-states, connected by a common culture and religion. The languages spoken throughout the region were all close, but not exactly the same. Even today, there are no less than 70 unique dialects of the Maya mother tongue. They are mutually intelligible, to a large extent, but nevertheless distinct.

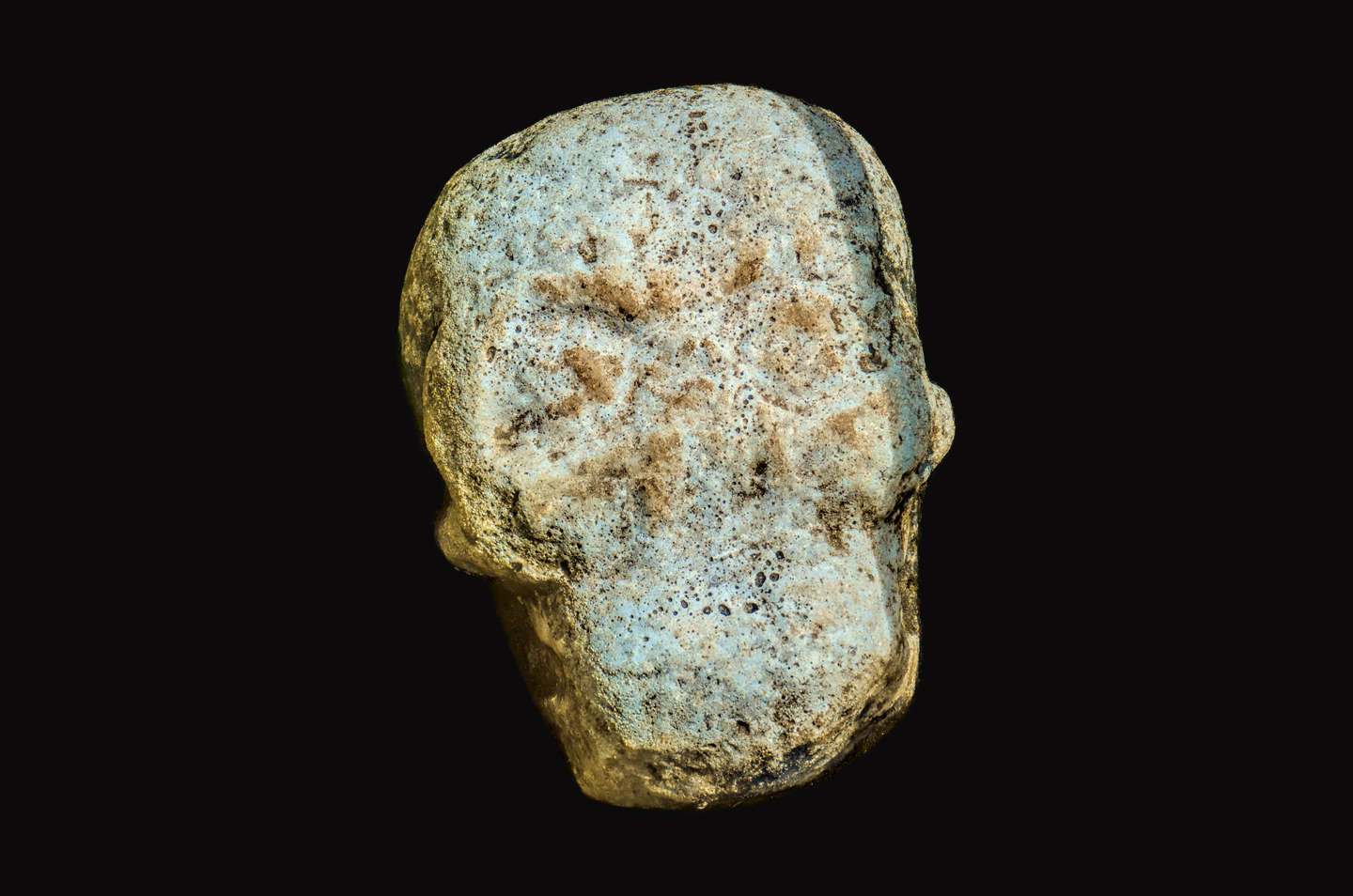

Back in the old days, alliances were constantly shifting between the dynastic leadership of these city-states. Upper-class society consisted of the nobles and priests, and, at the top of the pyramid, the kuhul ajaw, the holy lords, or kings, who were believed to have a direct connection to the gods of the animistic Mayan religion. Among other things, they had a divine mandate to rule. War between individual cities, and between regional alliances, was ongoing. In fact, war was as much a part of the loosely homogenized culture as their art and their technical and intellectual achievements, and was every bit as important to the Maya as agriculture. The fighting was necessary to enhance and consolidate power, to maintain or to wrest control of territory and resources, especially water sources, and to acquire captives. The captives were utilized as slaves, who were, in their turn, necessary for the monumental construction that was constantly taking place, especially in the larger cities. The construction was a form of one-upsmanship. By creating ever larger and grander palaces and pyramids, the ajaws demonstrated their superiority over their rivals, as well as over their own ancestors, and these massive structures could only be created with a steady supply of slave labor. The captives were also used as offerings to the Mayan gods. In the classic and post-classic periods, Mayan culture was subverted, at least to some extent, by that of the Toltecs, who edged into the area from central Mexico. The Toltec religion was fueled by human sacrifice, and a steady flow of blood: their gods demanded it. Want rain? Gimme some sugar–along with a few still beating human hearts, literally ripped from the victims’ chests in a horrifying public spectacle. Once the Toltec influence solidified, this carnival of death became the modus operandi for the Maya as well, and the bloody cult of Kukulcan, or Quezalcoatl, the feathered serpent, which originated further north, became an all-powerful force in the southern part of Mexico as well.

Coba

Coba controlled the area surrounding it by being bigger and badder than everybody else. The ajaw of Coba demanded tribute from the smaller cities and towns, and in return offered them protection, and shared resources, a social pattern that has repeated, with endless variations, in every corner of the world, throughout human history. The religion was a huge part of it as well, with Coba being the principle ceremonial center in the region, with the most important temples, the tallest pyramid, and the holiest high priests. Coba was also a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

Coba is estimated to have had at least 50,000 inhabitants at its peak, and covered an area of around 80 square kilometers. The city center is located around two lagoons, the Lago Coba, and the Lago Macanxoc. The site was first settled somewhere between 50 BC and 100 AD, by which point it was a thriving agricultural community. Most of the monumental construction was done between 500 AD and 900 AD, and most of the hieroglyphic inscriptions on the worn stelae (stone tablets) at the site were carved in or around the 7th century AD. The sprawling city was set up with hundreds of separate residential areas, each consisting of 15 houses surrounding a raised platform. Each of these platforms was connected to all the others by raised stone walkways–the sacbeob, which were paved with light colored stone that reflected moonlight, making it easier for bearers to transport loads in the cool of the night. The rulers of Coba maintained close relationships with the kings of Tikal, Dzibanche, and Calakmul, their most powerful rivals. It’s quite probable that they secured those ties through intermarriage of the noble houses. Based on inscriptions found on many of the stelae at the site, a great many of the rulers of Coba are thought to have been women.

It’s important to note that even though major new construction ceased after 900 AD, Coba was not abandoned at that time. The city remained occupied, and the original structures were still being maintained well into the 14th century, almost up to the time of the Spanish Conquest. When Chichen Itza started its rise to prominence, Coba was already beginning its slow decline, yet it remained a force in competition with the mighty Itza for at least a century. After 1000 AD, Coba’s star was definitely on the wane, but it maintained symbolic and ritual importance for religious and ceremonial purposes.

Thanks to the sprawling nature of the site, a visit to the ruins at Coba can be physically challenging. There are numerous groups of structures, all separated by a fair bit of distance. You can walk between them on wide pathways–the original sacbes, the white roads that were such an important part of the infrastructure at Coba, and one of the city’s most distinctive features. That’s pretty cool, when you think about it–to literally walk in the footsteps of the ancient Maya? But to tour the entire site requires literally miles of walking in those ancient footsteps, and in sweltering tropical heat. That combination can pretty quickly suck the joy out of your visit. Recognizing the need, local entrepreneurs established a small but well organized fleet of pedicabs for hire, and you can pick one up at the concession just inside the entrance for a nominal fee of about $10. These pedicabs will haul two people around to all the major building groups, and they’ll wait for you while you take your photographs. They follow the broad, smooth Mayan sacbeob, taking good advantage of this unique feature of the site. The guys that haul you around with these bikes aren’t tour guides, but they can at least tell you what you’re seeing, and they definitely save you a lot of sweat and effort. In my view, at this particular site? The pedicabs are well worth the cost. They might even be worth the guilt you’ll probably feel, watching that poor pedicab driver sweat and puff while you sit back in comfort. Coba is not more than two hours from Cancun, and while it’s not nearly as popular as Tulum or Chichen Itza, it still receives a significant number of visitors, and it can be quite crowded, especially in the afternoons.

The most impressive features at the site, aside from the sacbeob, include a well-preserved ball court:

With the sloping sides and the relatively large stone rings, it would have been far easier to score a goal here than in the huge ball court at Chichen Itza

Also, a large pyramid known as La Iglesia (the church):

The pyramid of the Painted Lintel:

The paint on the lintel of the temple doorway atop this pyramid is plainly visible, and something of a rarity. You need a telephoto lens to take a picture, because visitors aren’t allowed to get too close.

Also, the Ixmoja pyramid:

The tallest pyramid in the Yucatan, and one of the few structures of its size at any Maya site that visitors are still allowed to climb.

If you ever vacation in Cancun, and you decide to check out some Mayan sites? Go to Tulum and explore the ruins there–the setting is spectacular. If you can swing it, stay the night in the town, and take a look at Coba before you head back to the beach.

Muyil

Tulum, which was covered in my previous post to this blog, is 42 km southeast of Coba, and Muyil, also know as Chunyaxché, is another 20 km south of Tulum. This Mayan site was first occupied around 350 BC, and was still active until almost 1500 AD, making it both the earliest and the longest occupied site on the east coast of the Yucatan. The architecture at the site is of the Peten style, reminiscent of Tikal, in Guatemala. The ceremonial complex is situated on a lagoon, Sian Ka’an, which means “where the sky was born”. Back in the heyday of this small city, a series of canals provided access to the Caribbean from the lagoon, and the traders who plied the coast were able to paddle their way right into the middle of the town. Trade goods that passed along this route included jade, obsidian, rare feathers, salt, chicle (natural chewing gum), honey, and cacao. The cacao pods were actually used as a form of currency, which had a reasonably stable value. Muyil most certainly had strong ties to Coba, even though the smaller site was founded nearly 300 years earlier than the city that ultimately became its patron.

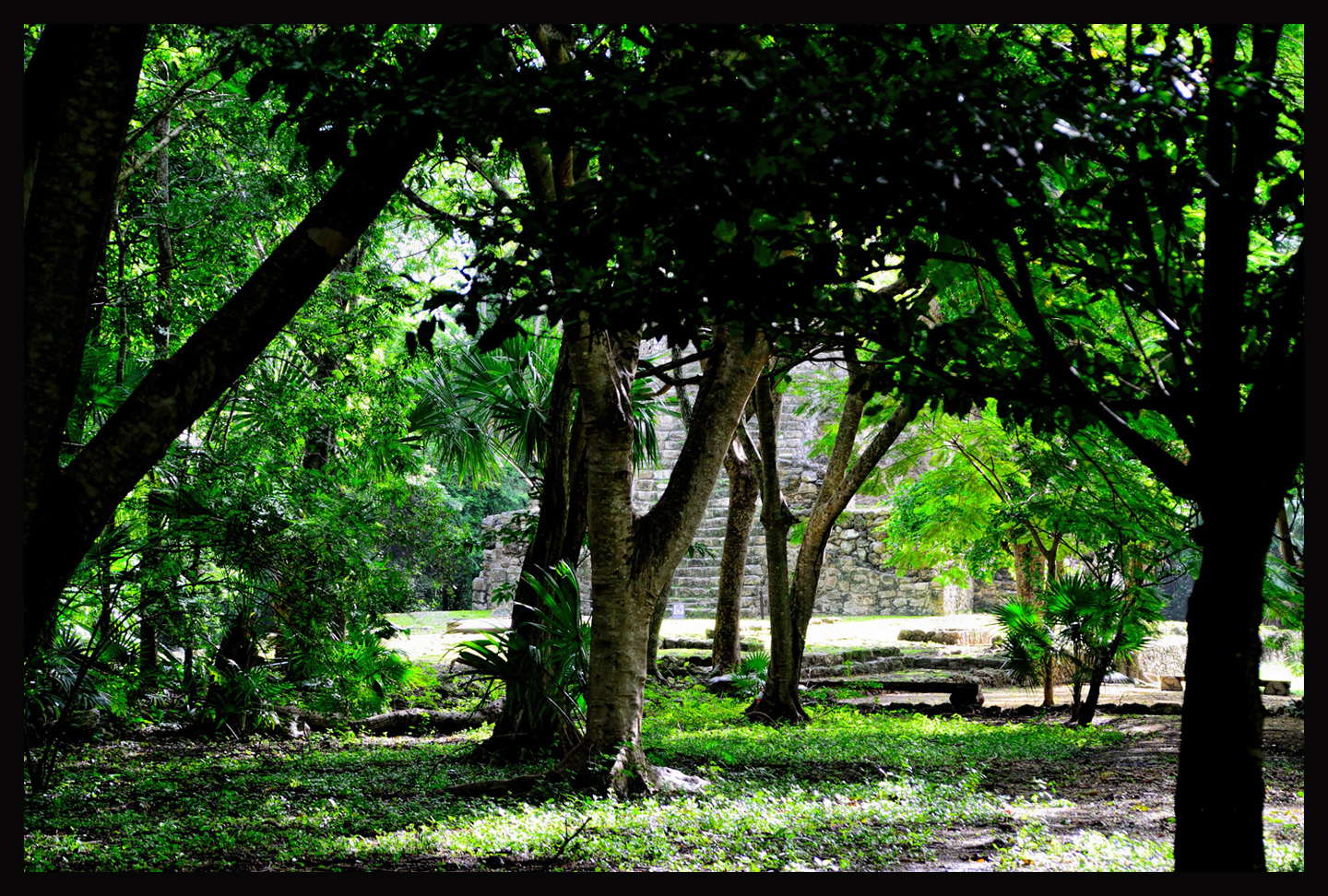

Muyil is a wonderful place to explore. Tour buses don’t come to this one. It’s still easy enough to get to, being so close to Tulum, but very few people bother to make the trip, so it’s not at all uncommon to have the whole site to yourself. That’s quite an amazing feeling, to wander the paths through the dense surrounding forest, the only sounds your own footsteps, or the song of birds. You come upon a clearing, and there, rising up out of the trees, are these extraordinary stone buildings, still partly overgrown by the encroaching jungle.

There’s not a soul around, just you, and you can let your imagination run wild. What this place must have been like 1,000 years ago, even 2,000 years ago? If only those stones could talk! Muyil will give you a taste of the Yucatan before they built Cancun, when the whole area was still off the beaten path and few people came this way. Sadly, that’s as much of a bygone era as the glory days of the Maya.

The large stepped pyramid at Muyil is crudely constructed when compared to the fancy structures at Chichen Itza and Uxmal–you can actually see that it’s nothing but a big pile of rocks stuck together with cement–but it’s actually quite stunning in its simplicity. The primary feature of this site is its peaceful atmosphere, completely devoid of vendors and hustlers, and all but devoid of visitors.

If you take my advice and overnight in Tulum, it would be a snap to visit both Coba and Muyil in the same day. Do Coba first, to try and beat the crowds. At Muyil, there will be no worries.

(Unless otherwise noted, all of these images are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

Click photos to expand the images

READ MORE LIKE THIS

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

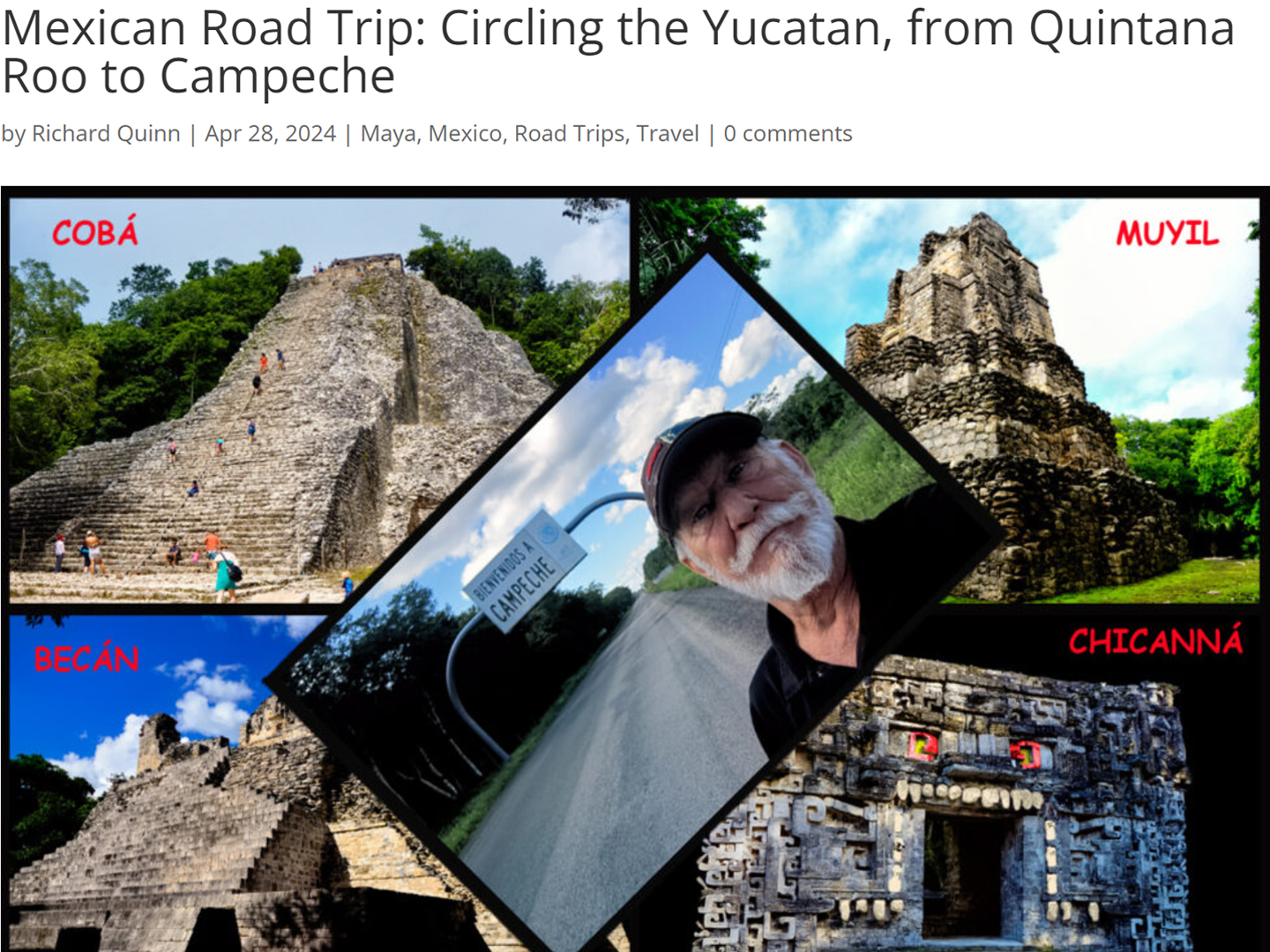

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn’t huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

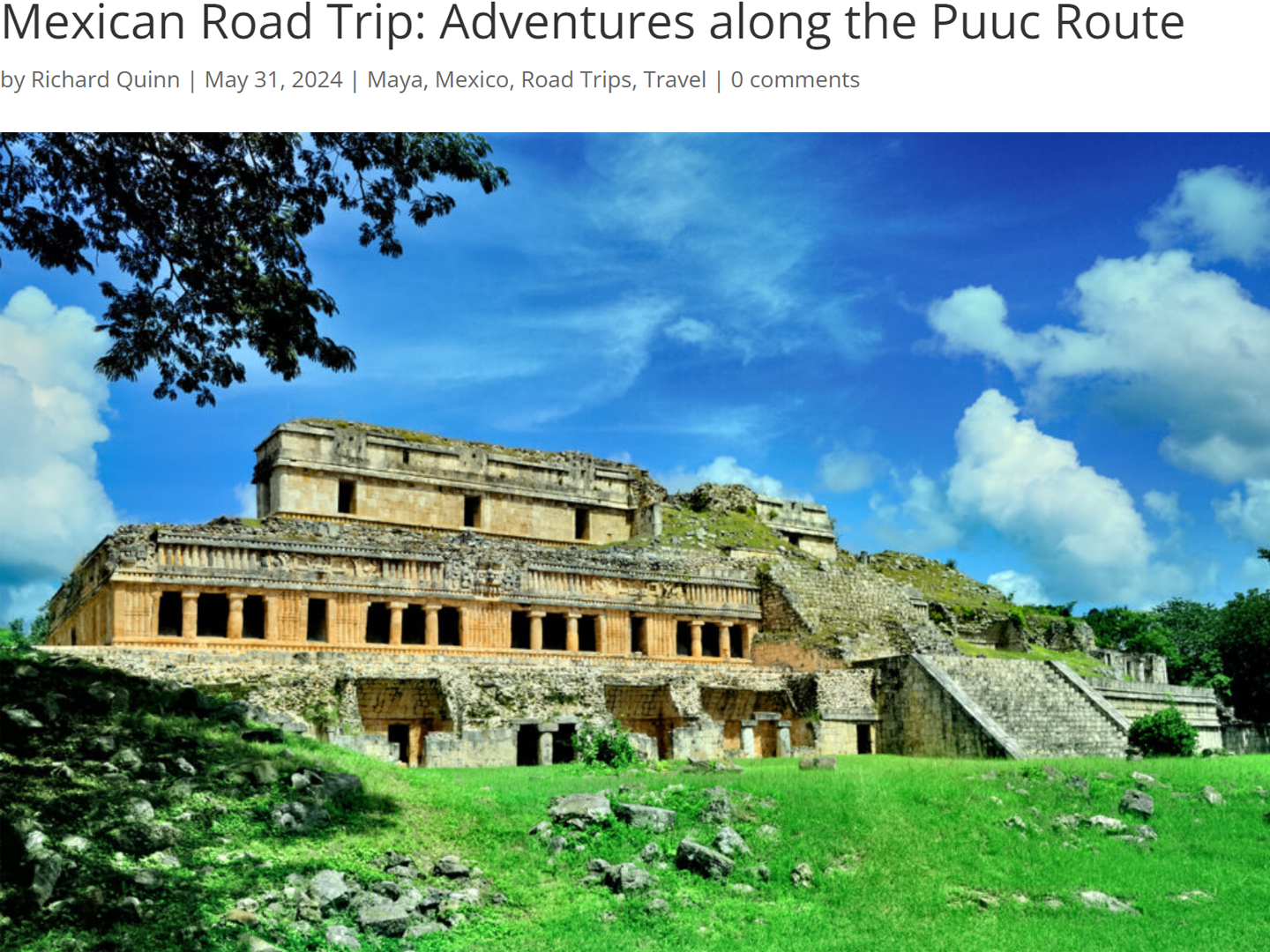

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

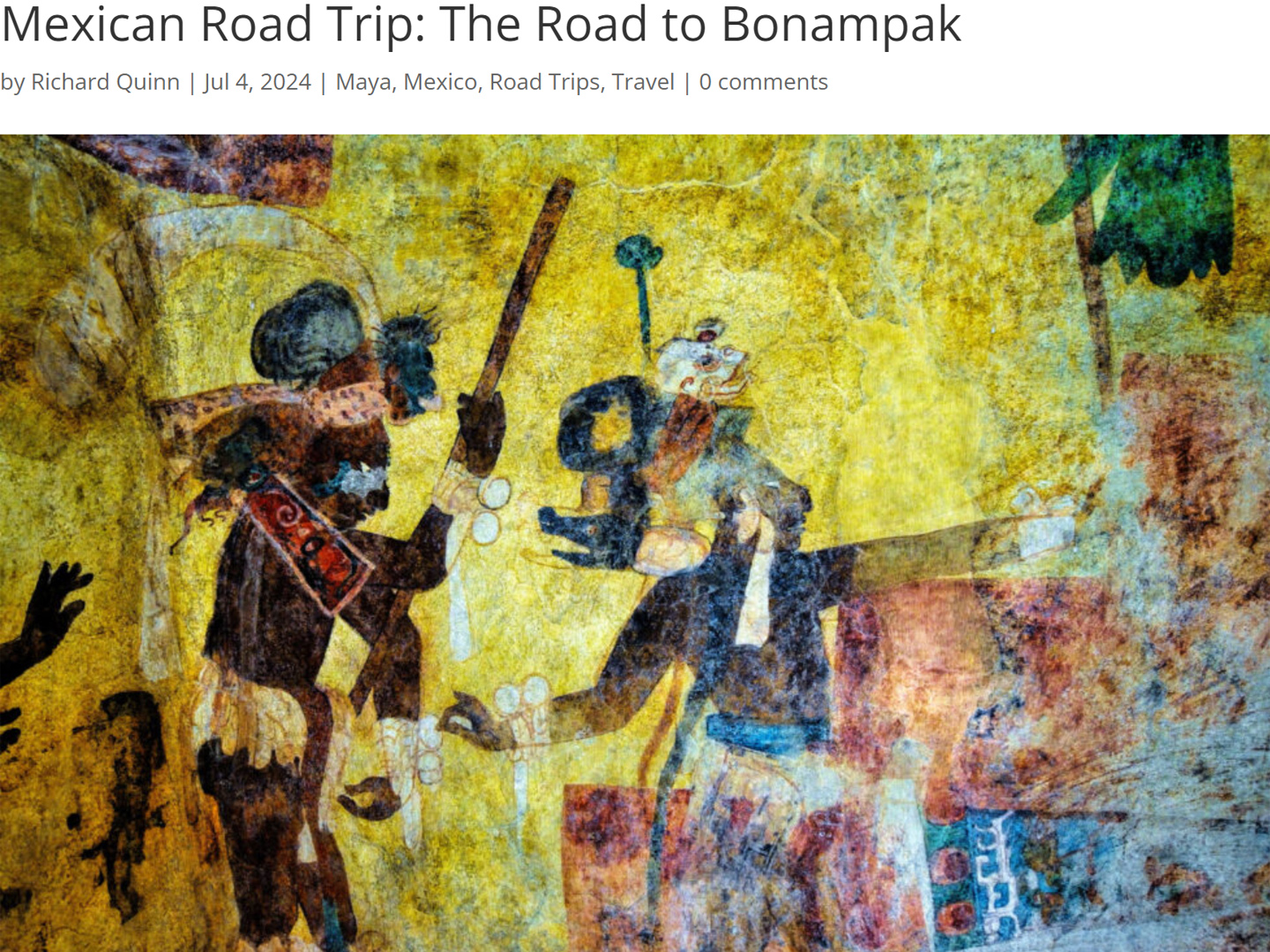

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we’re left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it’s 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in March, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico’s Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they’ve adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It’s a wonderful, colorful parade that’s all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

This series of posts is dedicated to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. “Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins” was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after “Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali.” We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Michael passed away in February of 2025, after 75 years of a life well-lived. He was unique, and he’ll be missed.

Michael Fritz (“Elmo”) 1949-2025

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments