DAY 17: FROM CAMPECHE BACK TO PALENQUE

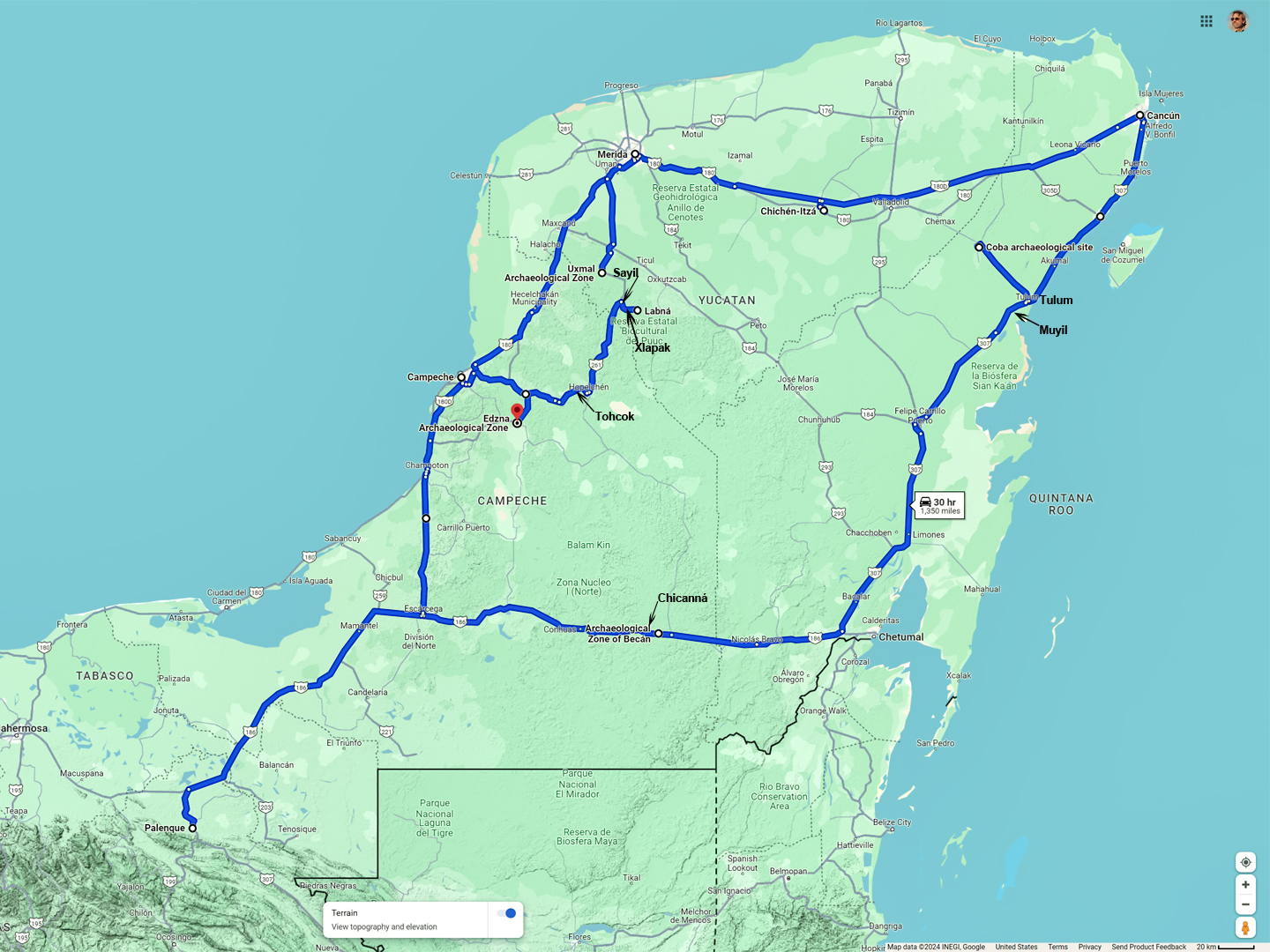

The 17th day of our road trip started out exactly the same as our 16th day: we had breakfast at our hotel, the Hotel del Paseo (near the historic center of old Campeche); then we hit the road. Over the course of the previous eleven days, we had completely circled the Yucatan Peninsula, visiting no less than a dozen Mayan cities, as well as the modern day cities of Merida, Campeche, Cancún and Tulum. We’d seen colorful festivals with costumed dancers performing in the streets, and we’d driven deep into the back country on highways that were an adventure unto themselves. All in all, our little expedition to and through the Yucatan had gone better than we ever could have hoped, but we were running out of time.

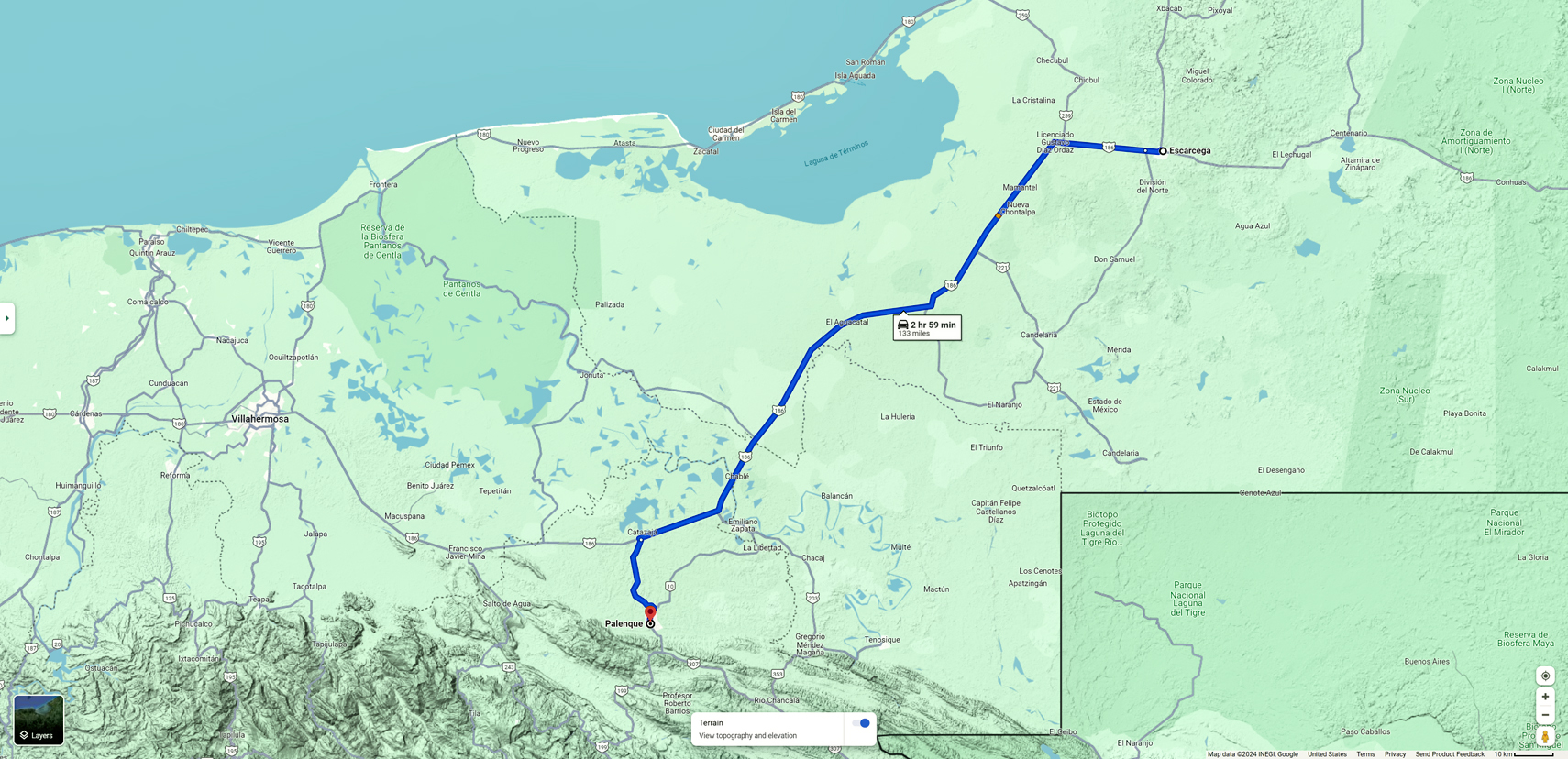

Day 17: This is where we’ve been, so far…

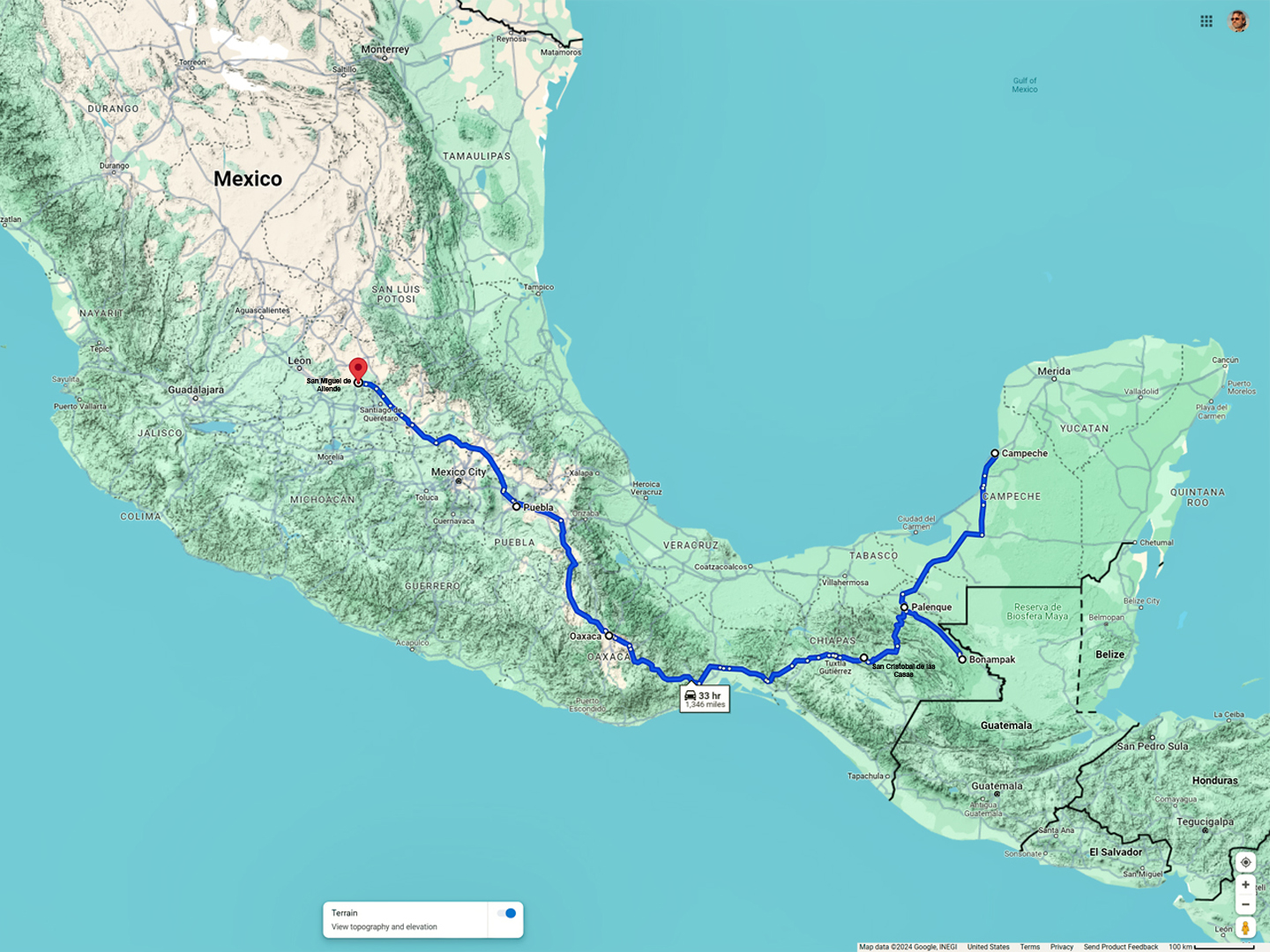

…and this is where we’re going next!

I had one last Mayan ruin that I wanted to see, a place called Bonampak, near the Guatemalan border in southern Chiapas. After that, we’d start the long drive north, passing through San Cristobal de las Casas and Oaxaca on our way to San Miguel de Allende, where we planned to celebrate the Day of the Dead festival at the end of the month. The itinerary was certainly workable, but there was more than 1,300 miles of driving involved, most of that on slow mountain roads. I set a schedule, and we were going to have to stick to it, despite the temptation to stay a bit longer in Campeche.

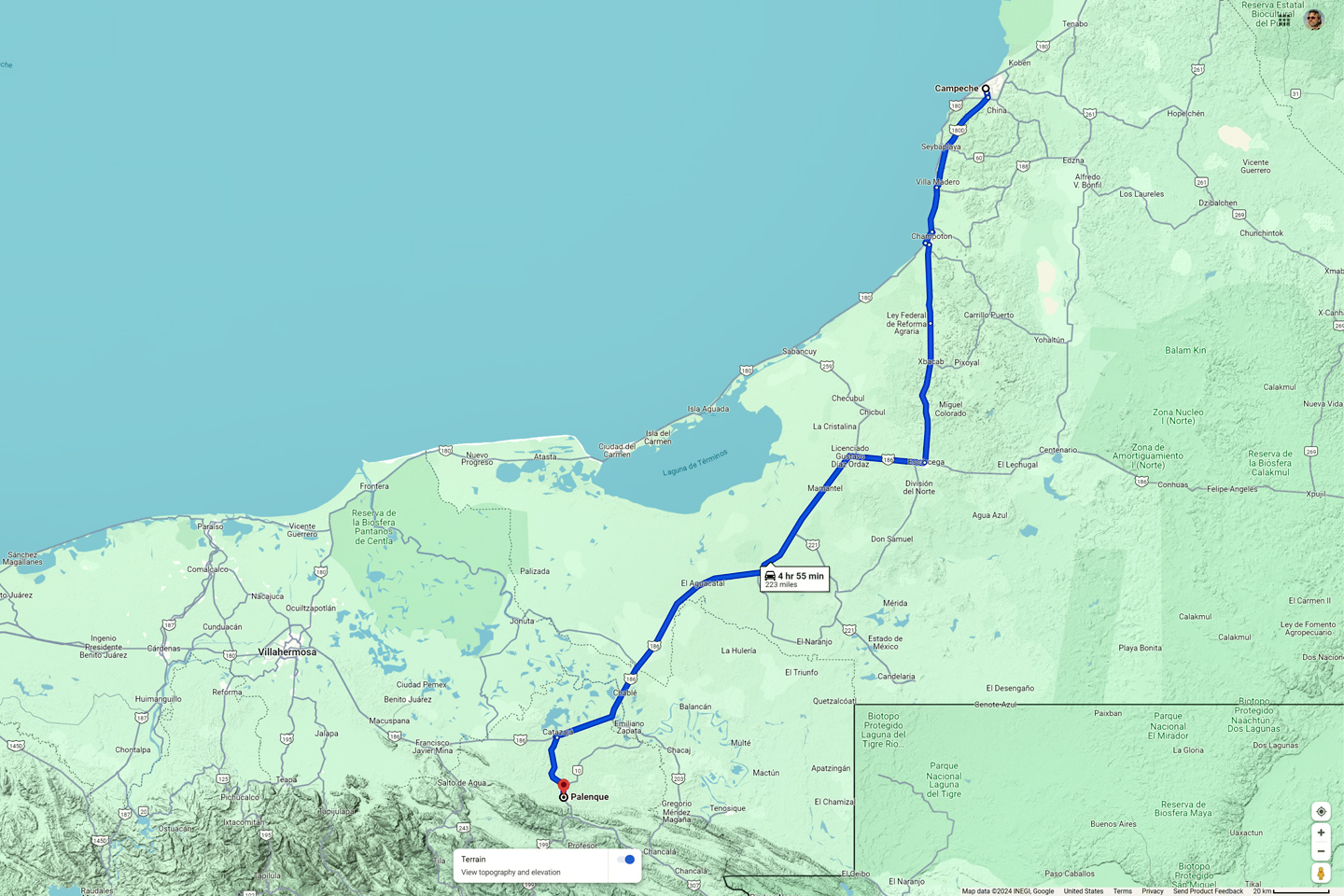

Our goal for Day 17 was to drive five hours south, back to Palenque, the place where our Mayan adventures first began. I’d used Expedia.Mx to book a room at a place called the Hotel Chablis, and we planned to use that as our base for a couple of days. Bonampak was three hours from Palenque, which meant a six hour round trip on a potentially dangerous rural highway. Add in some time at the ruins, that was likely to be a very full day. But I’m getting ahead of myself. We had to get to Palenque first, and that, by itself, was no small task.

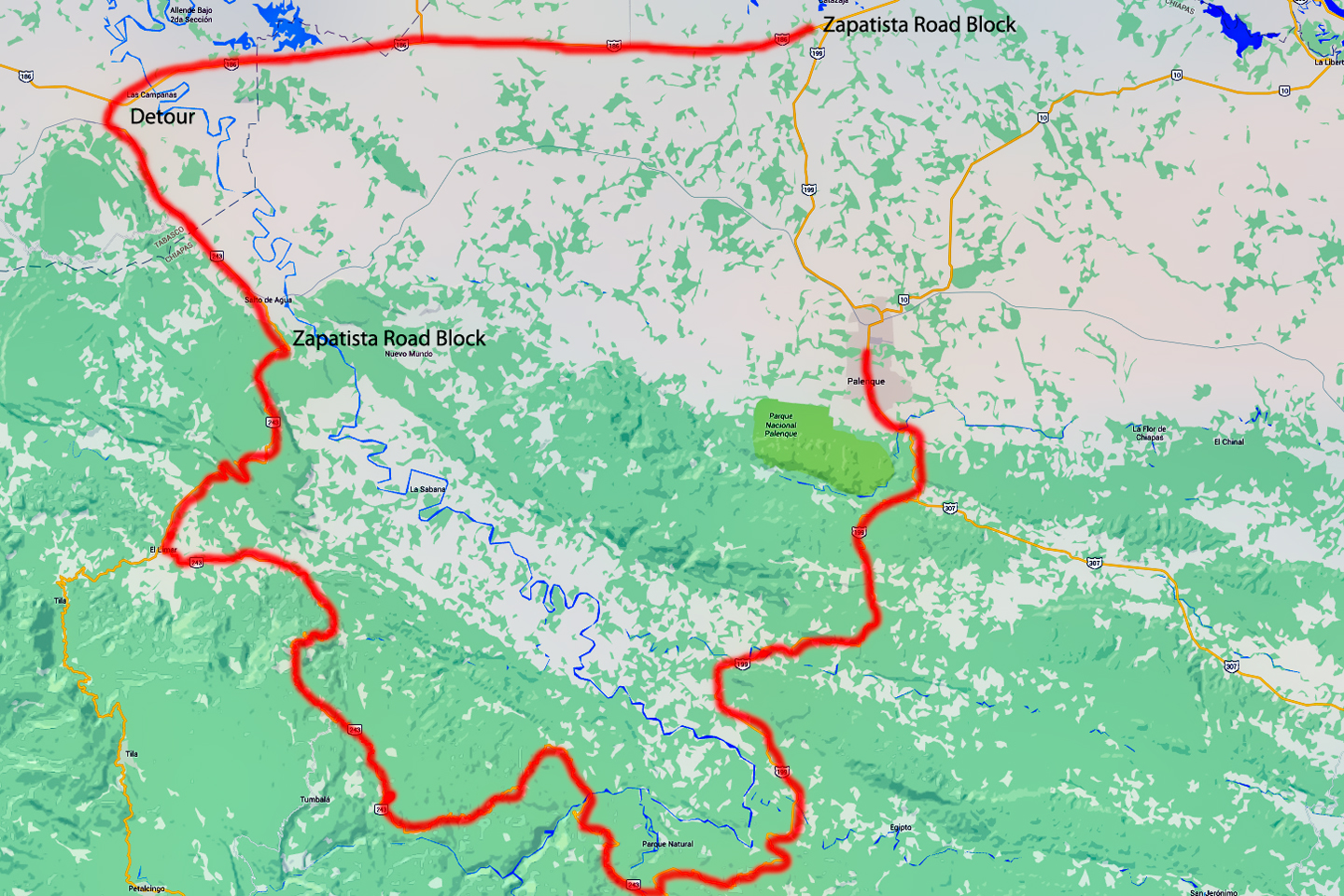

Route from Campeche to Palenque

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

Staging area for State Police in Campeche

Mexican cities can be hard to leave, and I mean that literally, as well as existentially. Leaving Campeche for points south, for example, we started out by driving north, because I wanted to make one last pass along the waterfront on our way out of town. Bad idea. That dropped us smack into the staging area for the Traffic Enforcement Division of the State Police, an elite squad of motorcycle cops.

Up to this point, all our interactions with Mexican Police had been perfectly cordial, but these guys were land sharks, notorious for pulling over tourists and shaking them down for supposed infractions. I got “the look” from at least one of them as we drove past, but they hadn’t started their shift yet, so I got us the heck out of there, as fast as I dared.

The scenic section of Campeche’s waterfront is the historic city center, where the remains of Spanish walls and fortifications create a unique ambience. North of downtown, it’s an ordinary beach, with thatch-roofed eateries and other businesses typical of Mexican beaches anywhere else in the country (all taking their cue from Cancún). We didn’t stop. We just drove on by all of that stuff.

MX 180-D

Any serious discussion of the condition of Mexico’s highways will always begin with a recommendation: whenever there’s a choice, you should always use the Toll Roads, which are faster, safer, and generally more free of hazards than the libre (free) State Highways. Leaving Campeche, we took our first opportunity to jump on MX 180-D (the “D” indicates a “Cuota,” a Toll Road).

Mexico’s Toll Highways (Cuotas) are modern and well-maintained.

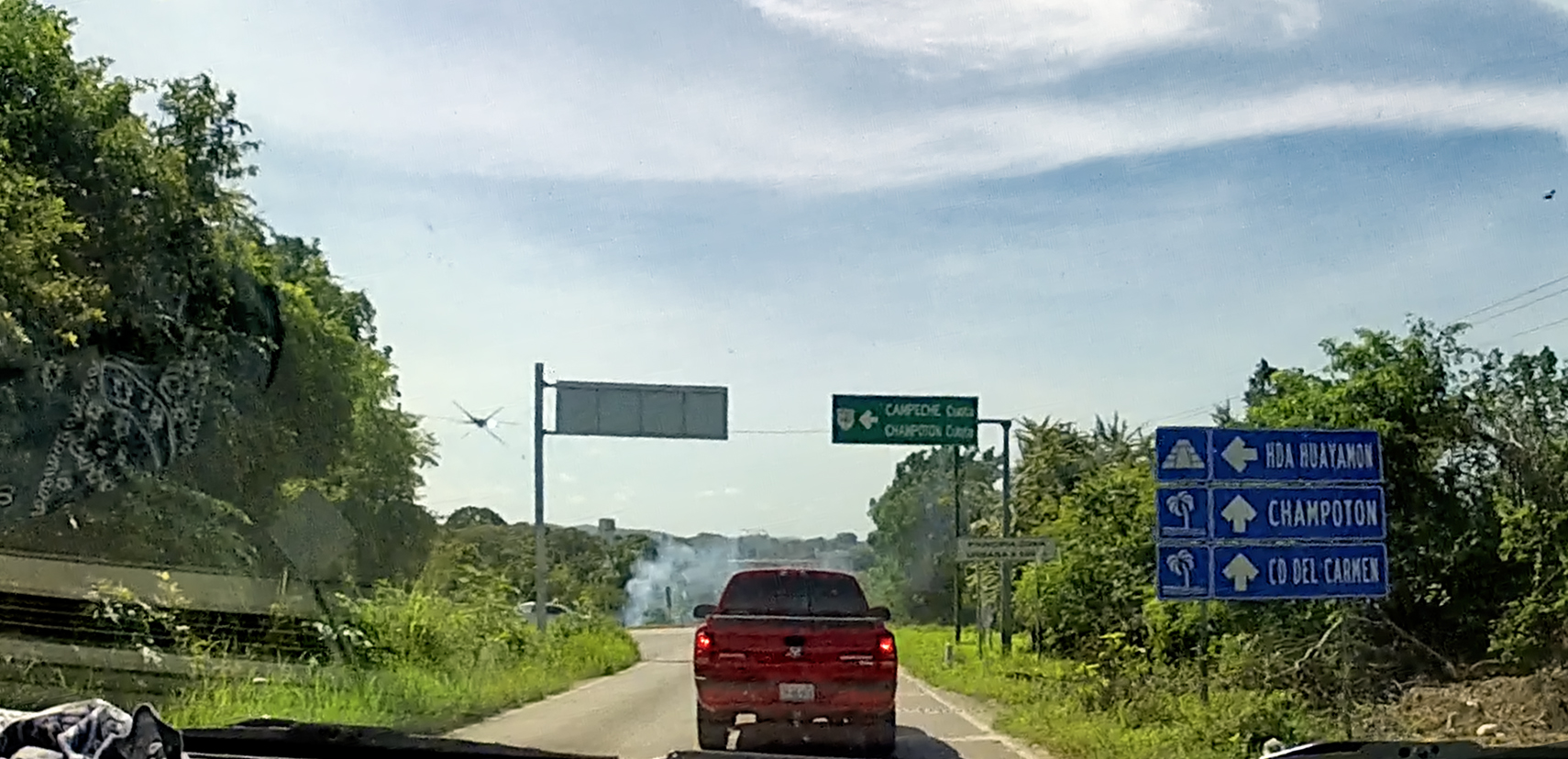

We pulled up to the booth, paid the toll, and sped off towards Champoton, a beach town that’s about an hour south of Campeche. Unfortunately, the Toll Road ended after just ten miles, and merged with MX 180 (without the “D”). This was a “libre,” highway, so it wasn’t divided, and there was just one lane in each direction, but in this case, that wasn’t so bad. The pavement was in good condition, and traffic was light, so we made good time. The road hugged tight to the coastline, a beautiful stretch that looked a lot like California. There were even a couple of surfers, out there scouting for waves. Then we passed a guy with a bicycle, pulling a trailer full of recyclable cans, while simultaneously pushing a cart full of something else, and flying a Mexican flag. (Come to think of it, even THAT could have been in California!)

Scenes along MX 180, the coastal highway south of Campeche

Once we got to Champoton, we ran into a surprise roadblock, with Municipal Police selectively stopping traffic in the middle of a busy street. Apparently, old gringo tourists driving Jeeps weren’t on their radar at that particular moment, because they waved us on, without so much as asking for our papers.

Local Police were selectively stopping vehicles in Champoton.

Ordinarily, they would have been stopping everyone, asking to see identification and the like, so we wondered who, or what, they were looking for.

Driving through Champoton

Champoton, like most beach towns, seemed like a nice place, even though all we really got to see was the busy main drag. Unlike the Toll Roads that bypass the cities and towns, the “free” roads pass through the middle of everything; it’s interesting, but super slow. We found the turnoff to Escarcega, and stopped for coffee at “The Italian Coffee Company.” There was something happening at the fairgrounds involving livestock, infusing the salt breeze with the unmistakable aroma of manure.

Road Junction: this way out of town!

Gringo style Coffee Shop

Fairgrounds, with an unmistakable aroma of apple pie–horse apples, and cow pies!

We parted ways with the ocean after that, and followed the State Highway fifty miles south to Escarcega. This was our third pass along this same stretch of road. The first time, we drove through quickly, on our way to Merida. The second time, we were headed back to Campeche from Tulum, but we ran out of daylight by the time we got to Escarcega, and elected to stay the night there, rather than risk driving in the dark.

Scenes along the road in Escarcega

More local Police action. Was it a regional exercise–or a manhunt?

Driving through again this morning, the town looked different; busier, and nothing about the place seemed familiar. In the downtown area, the local police were out in force, selectively stopping cars, the same type of action we’d just seen in Champoton. Was it some sort of regional manhunt, or a response to a threat? A training exercise? Or just a coincidence?

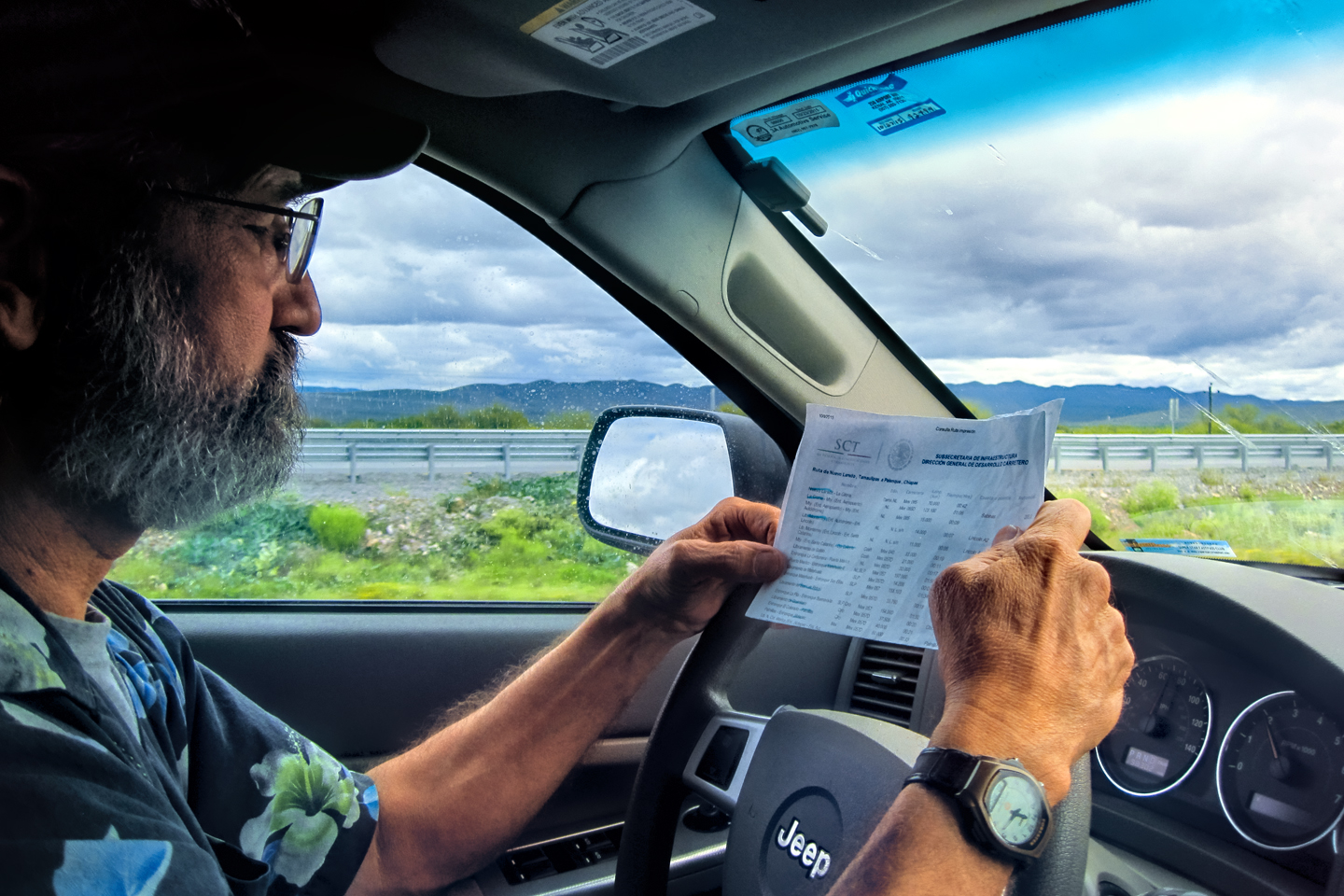

Scenes along MX 186: 1.) Trash recycling center; 2.) Horse refueling stop; 3.) Local passenger van; 4.) Studying the map

Beyond Escarcega, we jumped on MX 186, another road we’d driven before, and we followed that west, and then southwest for more than 100 miles, finally turning off on MX 199. That seemingly ordinary road junction was the scene of a huge protest the first time we came through the area; a Zapatista Road Block stopping all traffic entering the State of Chiapas. This time, we had clear sailing, and half an hour later, at about 4:00 in the afternoon, we finally arrived in Palenque. We found our hotel easily enough (thanks to the wonders of GPS), and had a couple of beers in the room to unwind from the drive. The Hotel Chablis proved to have been an excellent choice:

CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND

Click the Button for more info about the hotel.

Hotel Chablis, Palenque

We’d been having great success, using Expedia.Mx to search for hotel rooms, which is how we found this lovely place in Palenque. Modern and well appointed, with lovely gardens, a beautiful pool, secure parking, and a quite decent restaurant. It was located in a quiet part of town that we never would have found on our own, and best of all, back in 2015, a double room was only fifty bucks per night! (The current rate, in 2024, is $70 per night; still quite reasonable.)

That evening, I started feeling a little rough around the edges. I wasn’t sure if it was overexertion from all the hiking, stress from all the driving, or some combination of the two, mixed with tropical heat and humidity, lack of sleep, and questionable food. I wasn’t able to eat much of a dinner, and I crashed, much earlier than usual.

Day 18: A sick day in Palenque!

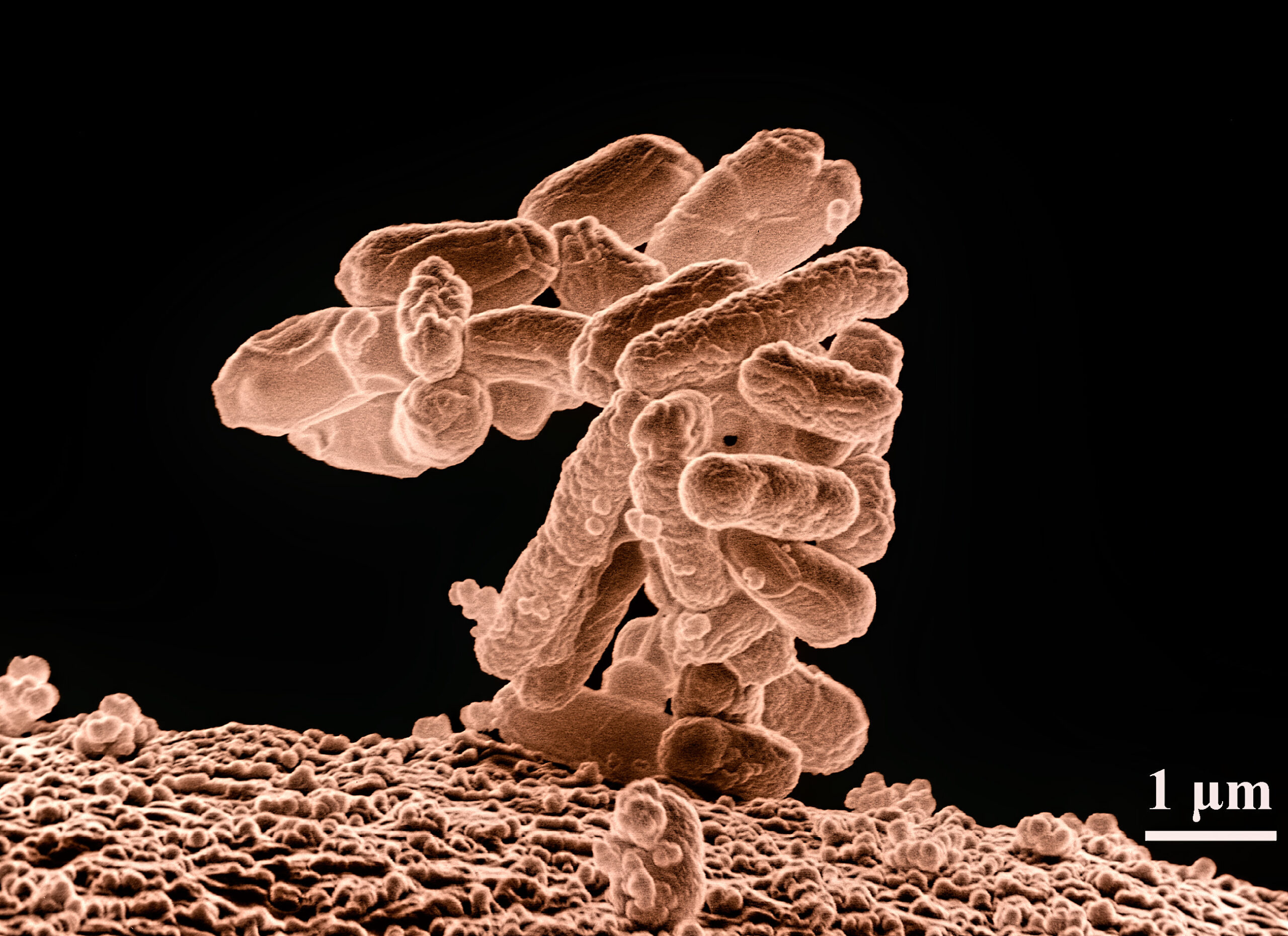

Back when I was a young guy traveling on the cheap, I had a cast iron digestive system, and almost never fell prey to the crud that strikes globetrotters when they fail to take proper precautions. Unfortunately for me, it had been more than forty years since that bygone era, and the cast iron part of me seemed to have rusted away. When I awoke on Day 18, I wasn’t merely unwell, I had the BUG! I’d had a wretched night. A tropical downpour just outside our open window woke me up at 1 AM, and I never got back to sleep, tossing and turning, sweating and freezing, running a low-grade fever, along with all those other classic symptoms that we don’t talk about in polite company. Travelers in Mexico have a name for this horribleness. They call it:

MONTEZUMA’S REVENGE!

Also known as the Turistas, or simply Traveler’s Diarrhea, this dreaded affliction will strike nearly everyone who travels far enough off the beaten path in Mexico (or anywhere else with less than perfect sanitation standards). E. Coli is a common bacterium that lives in your gut and is generally harmless. Problems occur when you come in contact with E. Coli that have been living in someone else’s gut. Even the tiniest amount of fecal matter is likely contaminated, and if you inadvertantly ingest any of that, even a single drop of contaminated water, odds are, you’ll get zapped by the curse. Symptoms include raging diarrhea (Boo-Yah!), stomach cramps, chills, and fever. Of course, there is no actual curse. Montezuma, the once and former Emperor of the Aztecs, has nothing to do with this disease. It rares up ↑ when you let your guard down ↓, and eat or drink something that hasn’t been properly sterilized.

Click the image (above) for more info from Mayo Clinic

E. Coli is everywhere (such is the world we live in). We tend to develop a resistance to the strains of the bug most prevalent where we live, but we have no such resistance to bacteria originating far from our homes. (For example, the bugs we might encounter when traveling internationally). Regardless of how and where you contract the condition, it will generally self-resolve after a couple of miserable days. Take Lomotil (requires a prescription) or Immodium for the diarrhea, and stay hydrated. Seek medical assistance if the problem lasts more than two days, or if fever rises above 102º.

The six hour round trip drive to Bonampak that we had planned was clearly out of the question. I really only had one play here: rest, recuperate, and pray for a speedy recovery!

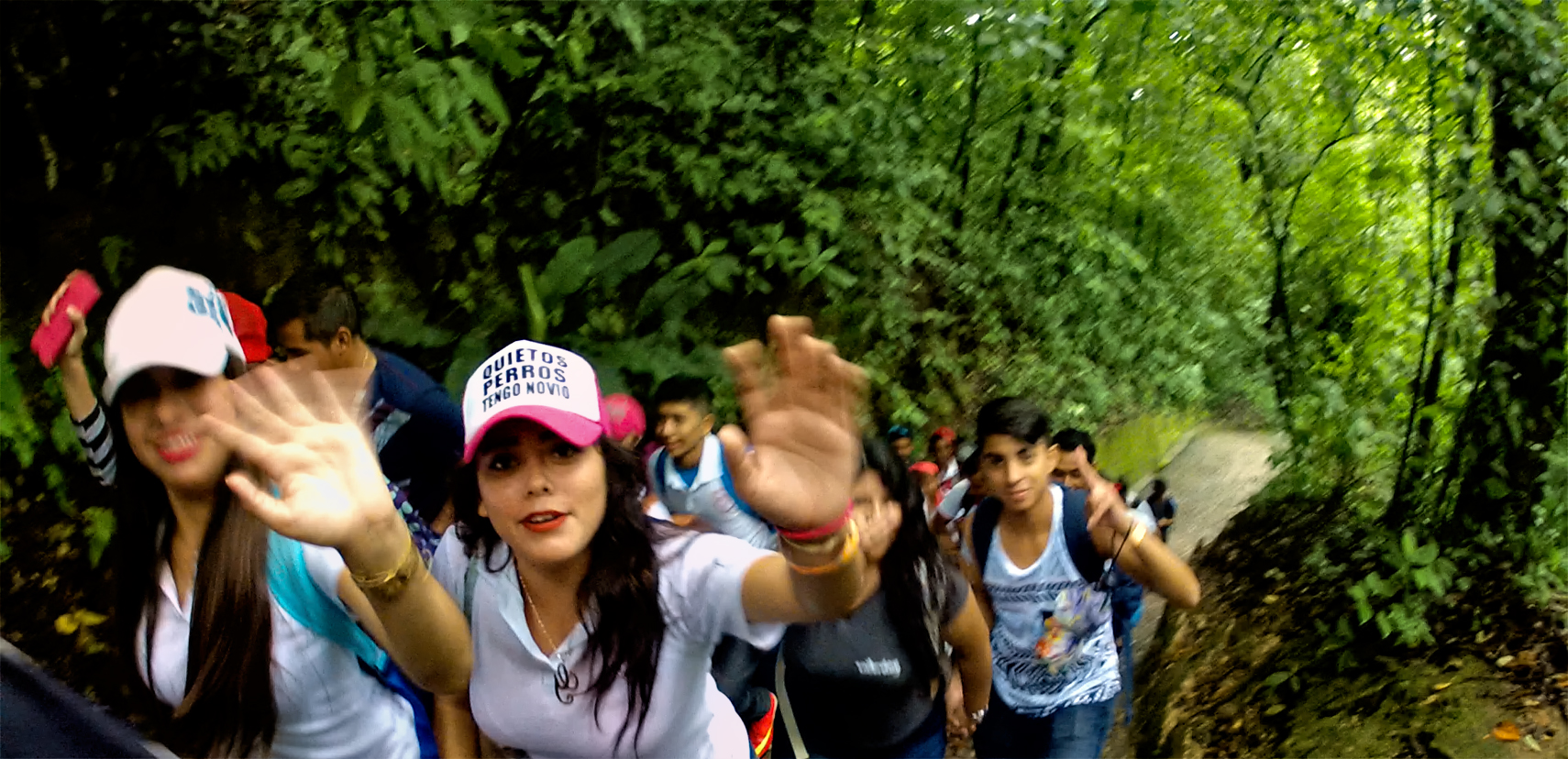

Michael, my shotgun rider, somehow managed to avoid the bug that laid me low, so while I spent the day in bed, Mike re-visited the Archaeological Park at Palenque. We’d had the ruins all to ourselves, the first time we passed through here, but this time the park was crowded with student tour groups. Crowd, or no crowd, I was sorry to have missed the opportunity to see that place again. Of all the Mayan sites we visited, Palenque was quite probably my favorite. (See earlier post: Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle.)

Tour groups at Palenque

By the end of the day, I was feeling much better, eating solid food, and keeping it down without a problem. The enforced rest did me a lot of good; we’d been running non-stop since crossing the border, so I definitely needed it. I had to wonder what was it that caught up to me. Montezuma’s Revenge from an improperly washed glass? Food poisoning from a bad shrimp? The symptoms were often similar, and traveling the way we were was a bit like Russian Roulette. Five times out of six, you walk away unharmed, but if you’re in the line of fire when the hammer falls on a loaded chamber, you’ll find out the hard way what all the fuss is about. My quick recovery was an enormous relief. We had a schedule to keep, after all, and I couldn’t afford to fritter away another day lying about in a hotel room.

DAY 19: A Stone’s Throw From Guatemala

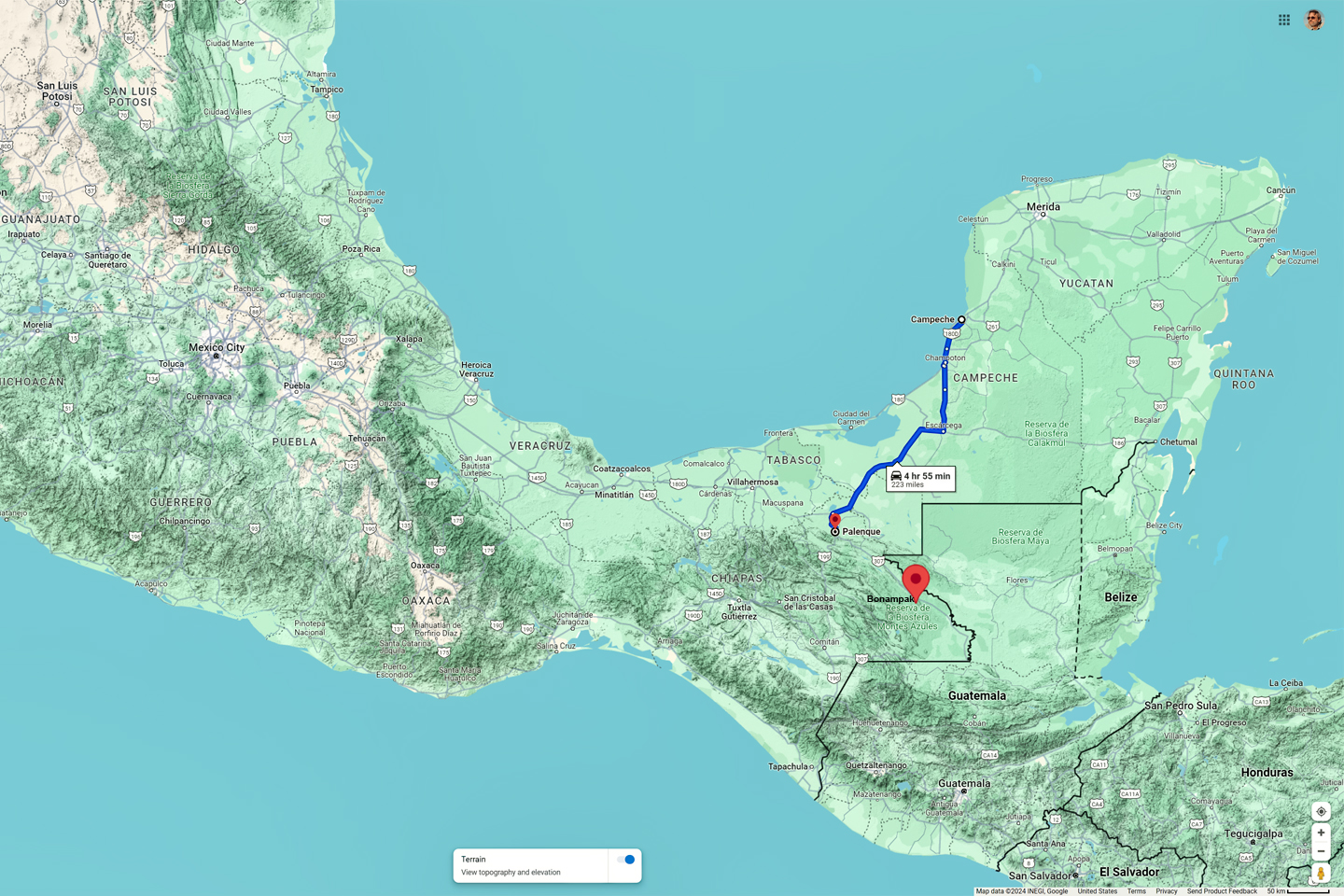

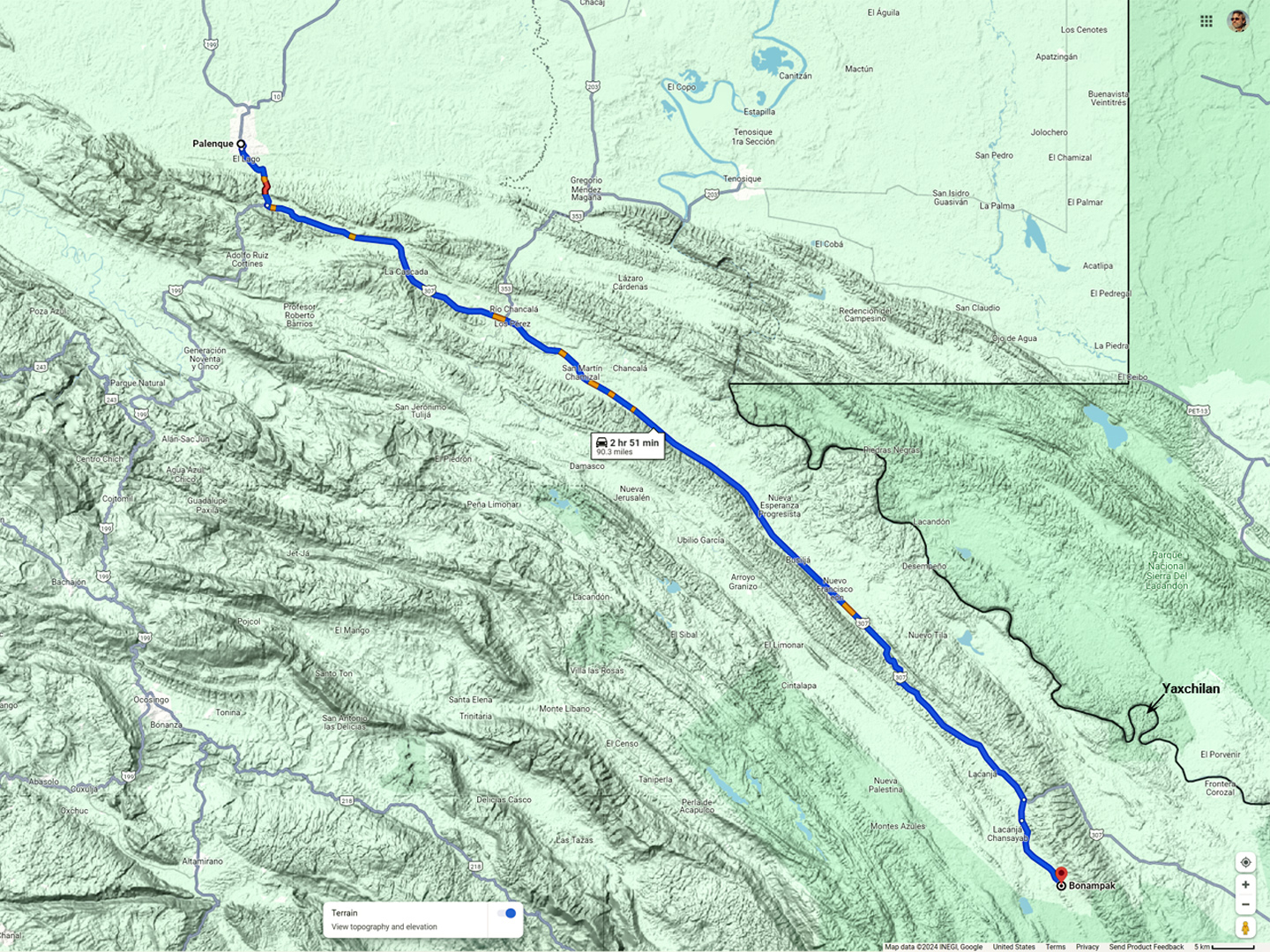

By the morning of Day 19, I’d recovered to the point that I was willing to take a chance on Bonampak, and when I say “take a chance,” it’s because there was more at risk than my health. Bonampak is 90 miles from Palenque, a slow, three hour drive, according to Google. The Federal Highway, MX 307, continues on from there, and runs within a stone’s throw of the Guatemalan border for almost 200 miles. According to the people at our hotel, the whole area is a smuggler’s paradise, the primary corridor for contraband of every description coming into Mexico from points south, and that includes unprecedented numbers of migrants and asylum seekers making their way north to the U.S. Border.

MX 307, from Palenque to Bonampak

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

The illegal activity, much of which takes place on or near the Highway, was happening mostly at night, under the cover of darkness; we were assured that the road was considered safe during daylight hours, because it was heavily patrolled by the military and the Federales. We were told to expect a lot of soldiers and road blocks, but not a lot of traffic, and as long as we were back in Palenque before sundown, we shouldn’t expect any trouble. We followed that advice, and indeed, we didn’t have any trouble, but keep in mind, this was in 2015, almost ten years ago.

In the time that has passed since our visit, the situation with the Cartels has gotten immeasurably worse, and the gangs now operate with impunity at all hours of the day and night. In an article dated January of 2024 (click the link), the Associated Press reports that Cartel gunmen are effectively in control of the roads in this part of Chiapas, and anyone wishing to visit the Mayan ruins has to pass through their checkpoints. Yaxchilan, a major ruin near Bonampak that was formerly accessible only by boat, is no longer accessible at all, at least, not from the Mexican side of the border, and Bonampak itself is not recommended for tourists (despite assurances from INAH, the National Institute of Anthropology and History, insisting that it’s safe).

Many of the guided tours that take visitors from Palenque to Yaxchilan and Bonampak have been suspended, a devastating blow to the local economy, which is heavily dependent on income from tourism. One guide who was interviewed said that it was getting to be like the Gaza strip down there: armed gangs shooting it out with one another, heedless of the innocents caught in the crossfire. If I was to go back to Chiapas today, I’d probably have to skip Bonampak, so I’m certainly glad that we went when we did. That little ruin was the cherry on the top of our Mayan adventures, unlike anything else that we experienced. Read on, if you’d like to know what it was like, when we drove:

The Road to Bonampak

Secure parking at the Hotel Chablis in Palenque.

Our hotel had a gated parking area. Oddly, my Jeep was the only vehicle using it during the time we were there. I got the sense that most visitors to Palenque arrive on buses, or else they fly in to the little airport. Road trippers from the U.S., like me and Mike, weren’t remotely common in this part of Mexico.

The 180 mile round trip we were about to take really wasn’t much compared to most of our driving days, but we were going deep into a very rural area, where we weren’t likely to find much in the way of services. We stopped at the Pemex gas station on our way out of town, and I asked the attendant to “llenarlo,” (fill it). We only needed a few gallons to top off the tank, but for all I knew, this might be our last chance to buy fuel before the end of the day. In the U.S., pump jockeys at service stations were a thing of the past, but in Mexico, they’re a fact of life, and for me, a nostalgic throwback to my youth.

Pemex station in Palenque: Last Gas Before Bonampak.

Attendants do the pumping; there’s no self-service!

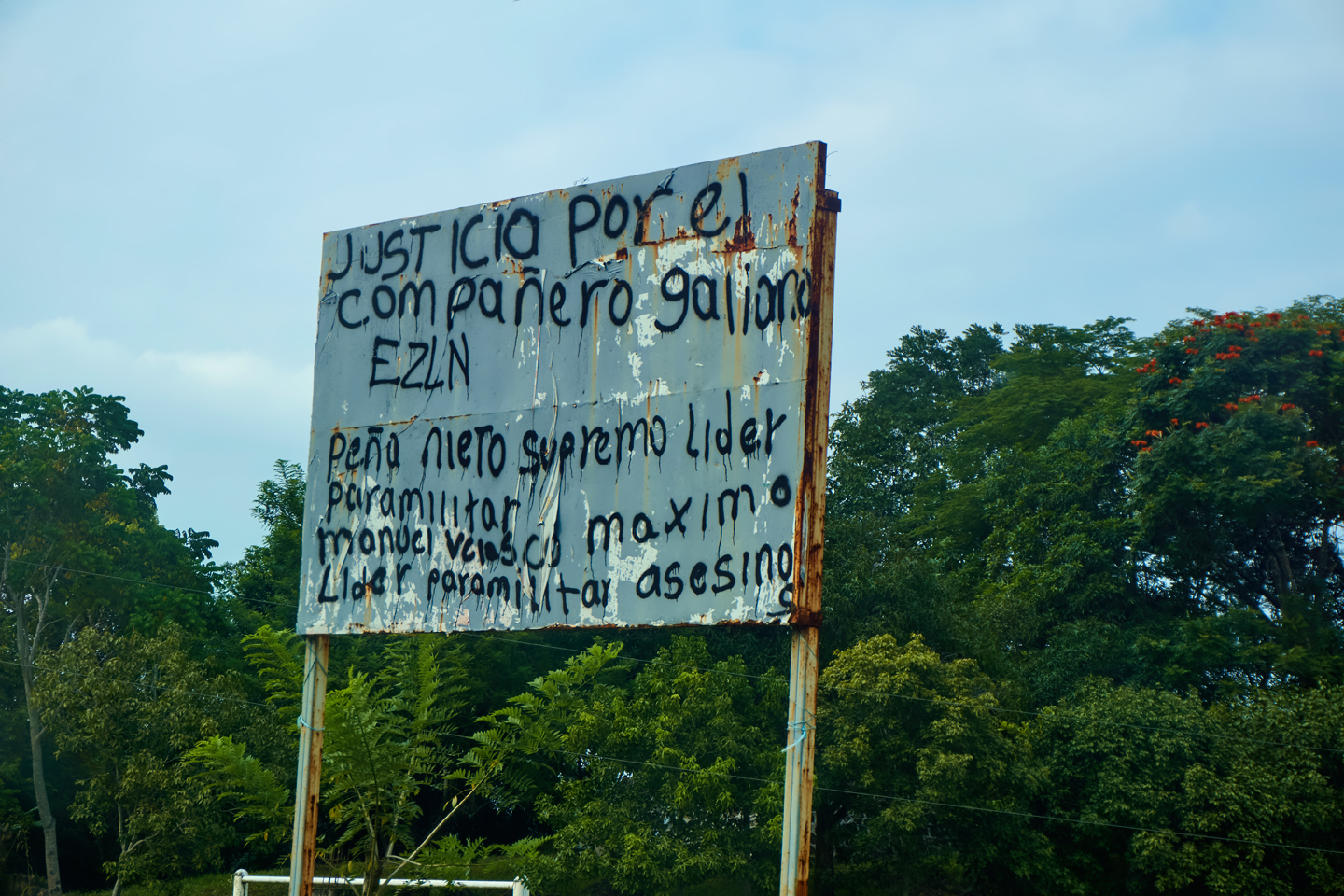

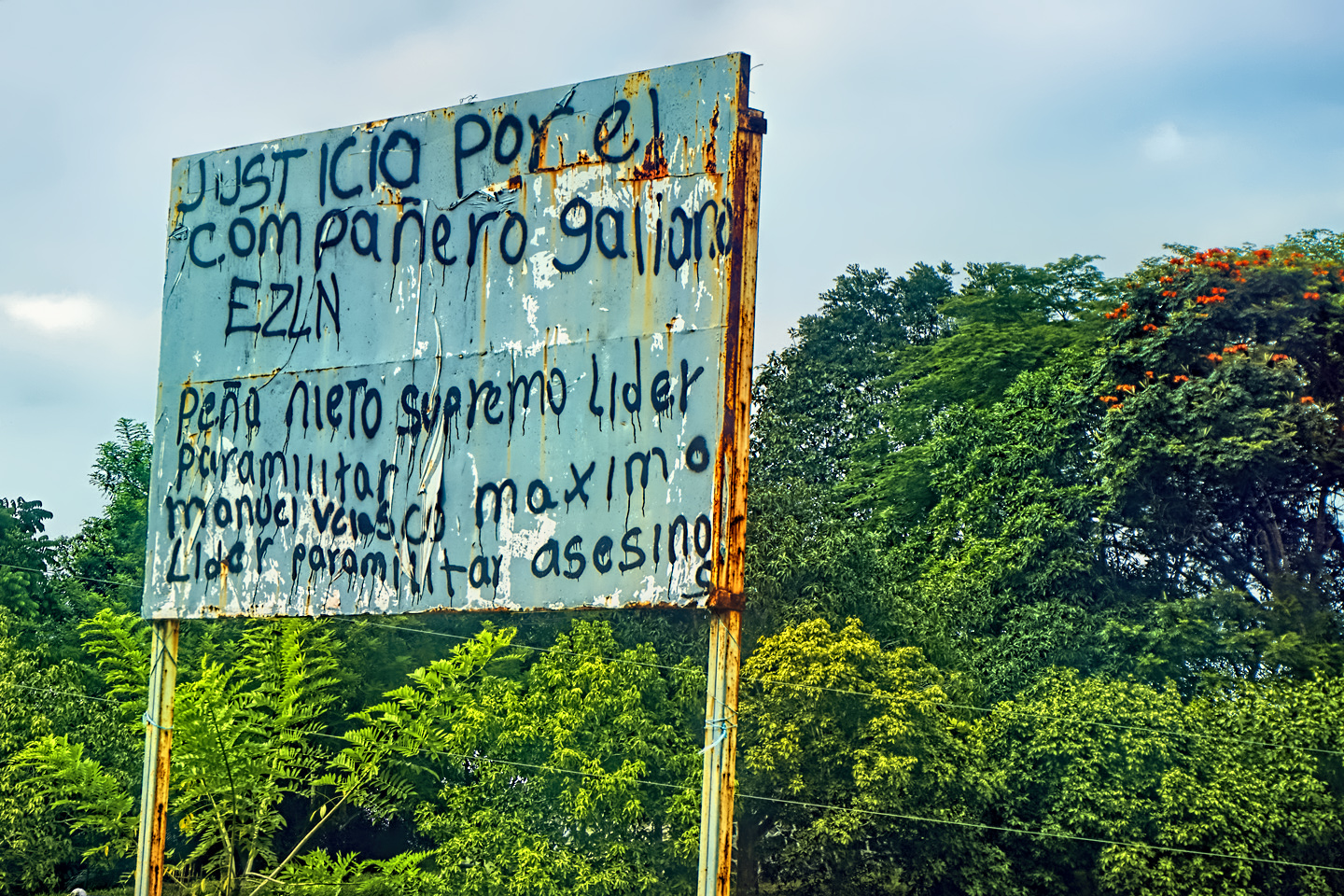

The route out of town was familiar: we started out on MX 199, the highway that crosses the mountains to San Cristobal de las Casas. We drove that road after our first visit to Palenque, two weeks before, but we’d only made it as far as Ocosingo before a Zapatista Road Block forced us to turn around. (See: Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas.) Most of the State of Chiapas was Zapatista territory, and we started spotting their road signs (below) as soon as we left Palenque. (Enrique Peña Nieto, referenced on the signs, was Mexico’s President in 2015.)

ZAPATISTA ROAD SIGNS IN CHIAPAS

Sign on the left:

“You are in Zapatista rebel territory. Here the people rule, and the government obeys. The trafficking of weapons, planting and consumption of drugs, sales of intoxicating beverages, illegal trafficking of wood and destruction of nature are strictly prohibited.

Good government board, Northern Zone”

Sign on the right:

Justice for the murder of comrade Galeano ELZN.

Peña Nieto: Supreme Paramilitary Leader.

Manuel Velazco: Maximum leader for the murderers

Welcome! San Martin-Chamizal; Palenque, Chiapas

The organization of civil resistance: “Light and strength of the people.”

We reject the application of structural reforms starting in 2015, the entry of INEGI, federal, state, and municipal police, and exploitation of natural resources. Don’t believe Televisa and T.V. Azteca. Narco-government, Narco-party.

Better get organized and fight, we are going to take power as an organized people and build a new constitution and a constituent congress.

Peña Nieto: Guilty of forced disappearances. Not one more, enough crimes.

Fortunately, the road to Bonampak was not one of the routes that was subject to blockade, so once we made the turn onto MX 307, we were pretty much safe from delays due to political protests.

MX 307

We’d driven a number of isolated rural highways, most recently when visiting the Mayan cities along the Ruta Puuc, but this one, MX 307, was a special case. It is the ONLY road for many miles around, which makes it a critical lifeline for area residents; the only way to get from A to B. We drove by a group of kids walking to school with their backpacks, as well as farmers doing their work on horseback. It was as if the different generations were living in different centuries.

Scenes along MX 307: Palm oil plantation

Kids walking to school?

Horses resting in the shade.

Woodcutters, awaiting transport.

Truck loading produce.

Road Hazards: Downed trees blocking a lane, and a mudslide that nearly closed the road

The highway was built through the heavily forested hills of the Lacandon jungle. It’s the kind of road that requires continuous maintenance: we passed one area where newly downed trees blocked the lane, and another where two guys with shovels were working to clear a mudslide that nearly closed the road altogether.

In the land of the Maya, any time you see an isolated hill with a conical shape, good odds that it’s a pyramid that’s never been cleared. This formation (right/below) is a good example. There are hundreds of Maya sites that have been identified, but never excavated due to lack of funding.

A suspicious hill in a field beside the road: if it looks like a pyramid, it probably is one!

Scenes along MX 307.

There were no towns of any size along this route. Instead, there were clusters of ramshackle homes strung out alongside the highway, a few here, a few there. The people’s lives and economic status were on full display for anyone driving past, out there on their wide open porches, and hanging on their clothes lines.

“Abarrote Dos Hermanas,” (2 Sisters Grocery).

Some of the homes had traditional thatched roofs, a time-tested construction method that has the advantage of low-to-no cost for the materials and labor, which is usually supplied by friends and neighbors, using dried palm leaves grown locally and prepared in advance. A big enough group will knock out a roof like that in less than a day. There are two problems with thatched roofs: they require frequent re-weaving to keep them from leaking, and they harbor entire colonies of creatures, ranging from fruit bats and mice to scorpions, venemous millipedes, and “kissing bugs,” the blood-sucking pests that spread Chagas disease. That’s the main reason why anyone with the means will go for corrugated sheet metal instead, despite the fact that metal roofs are much more costly, as well as being unbearably hot when the sun shines on them, and prone to blowing away in the more serious tropical storms. They’re considered worth the expense, the discomfort, and the risk, because metal roofs are so much cleaner, they require no maintenance to speak of, and they produce a lovely tympanic symphony in a hard rain.

One thing about this road that was a serious annoyance was the extreme prevalence of Topes, the speed bumps installed for the purpose of slowing traffic in populated areas. MX 307 had more topes over less distance than any road we’d driven, and that was really saying something. Every house, every bus stop, every side lane, they all had their own Tope, sometimes more than one (a small PRE-Tope, warning of a larger Tope yet to come). Both Mike and I were constantly on the lookout, but some of the older bumps were so blackened by skid marks that they blended with the asphalt, making them easy to miss. We hit a few of those booby traps pretty hard, despite our best efforts.

Topes, speed bumps made of concrete and asphalt, are increasingly common in every part of Latin America. When strategically placed by road junctions and in populated areas they serve as a cost-effective method for passively enforcing speed limits. Poorly designed Topes can damage your vehicle if you hit them too hard, so drivers learn rather quickly that it’s best to treat them all with cautious respect. Some Topes are wide, and gentle, painted in bright yellow stripes, marked by multiple warning signs as you approach. Others come at you with no warning at all, and they’re sharp enough to blow your tires if you strike them at speed. (It’s not uncommon to see a shack beside the road near a bad Tope, advertising Servicios Vulcanizadora (Vulcanization: old-fashioned tire repair). Regardless of what you might think of them, Topes are an irrefutable fact of life on Mexico’s Highways. All you can really do about them is SLOW DOWN! (Which is pretty much the whole point). This is a challenge you don’t get to win.

When we got close to Bonampak, we had to stop and pay a fee of fifty Pesos each for entry to the “Zona Arqueologica.” The attendant explained that there would be separate fees of 100 Pesos each for entry to Bonampak or Yaxchilan. A mile or so up the road, we were stopped again by a young Mayan lad, who expained the setup.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

Unlike the other Mayan cities we’d been to, visitors were not allowed to drive themselves to either of these sites. We weren’t planning to go to Yaxchilan, but if we did, the closest they allow you to get by road is a parking area near the Usumacinta River. For a fee of 400 Pesos each, a launch takes you down river to the ruins, and brings you back again. As for Bonampak, private vehicles were not allowed on the road from the highway, so visitor parking was here, by the turnoff from MX 307. There was a van that would shuttle us the last five miles to the ruins (and back again), for a fee of 100 Pesos each. The extra fees were unexpected, but I honestly didn’t mind paying. The money went to a co-op that benefitted the local community, and the income was obviously much needed.

BONAMPAK

The van dropped us off where the road ended and the footpath began, but we still had to walk at least half a mile to the site. The day was mostly sunny with a few high clouds, so it was quite warm, and terribly humid. I wondered why the van hadn’t taken us the whole distance. Why make us walk all that way in the heat? Mike surmised that they were keeping us humble, and that may have been true; Bonampak is still sacred to the Lacandon Maya, and they’re very protective of their property. When we reached the ruins, we were met by a half dozen Mayan men from the nearby village. Guardians, there to keep the place safe from us tourists.

Satellite Views of Bonampak

The long walk in to the ruins

Inside the Transport Van

Site Guardians (Mayan men from a nearby village).

Thatch-roofed palapa used by site caretakers.

Just inside the entrance, there was a shady palapa, atop a low platform edged by ancient steps. That’s where we paid our 100 Peso entrance fees, to a different group of Mayan villagers. This was a solemn transaction, duly witnessed and recorded. Each of us was given a receipt, which we were instructed to show to the guards who controlled access to the temples.

There didn’t appear to be all that much to see here. Front and center was an unremarkable, medium-sized pyramid, topped by several smallish structures, some of which still bore traces of faded red paint:

Main pyramid and temples at Bonampak. Traces of the original red paint are still visible after 1200 years!

There were also several free-standing stelae, each protected by a small canopy, and a lesser pyramid, topped by a rectangular building that was itself protected by a free-standing roof. That building was the reason why we’d come to Bonampak. Officially known simply as “Structure One,” it is smallish, some fifty feet long, and twelve feet wide, divided into three rooms, each with its own door to the outside.

Bonampak: Structure One, protected by its own free-standing roof, is on the right

After Bonampak was abandoned, somewhere around 800 A.D., those doors were sealed off by an accumulation of debris, and they remained that way for more than a thousand years. On the outside, the temple was just another nondescript mound of rubble, half buried by tropical vegetation. On the inside, out of view of the world, Structure One was protecting something wonderful.

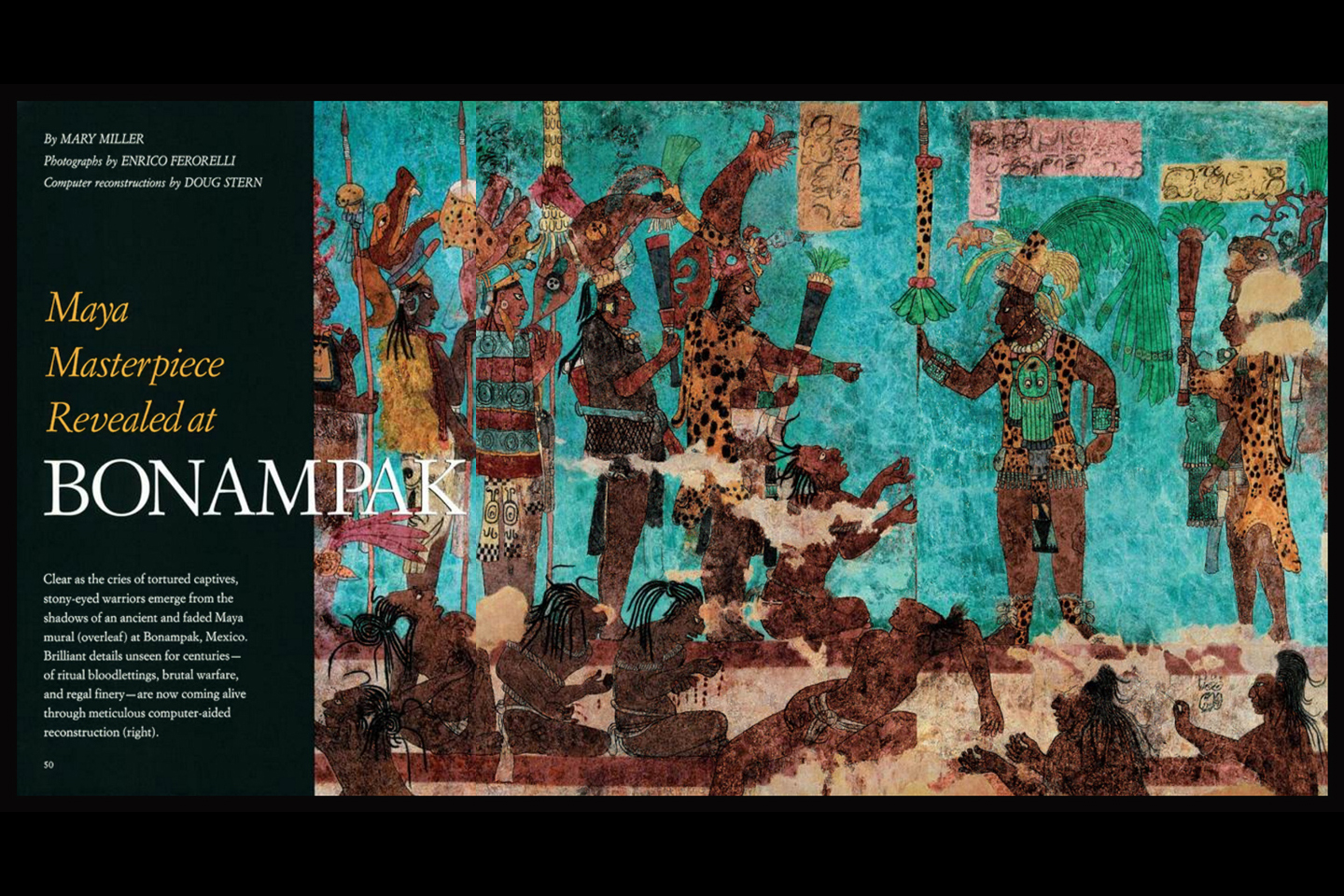

Several views of Structure 1, the Temple of the Paintings

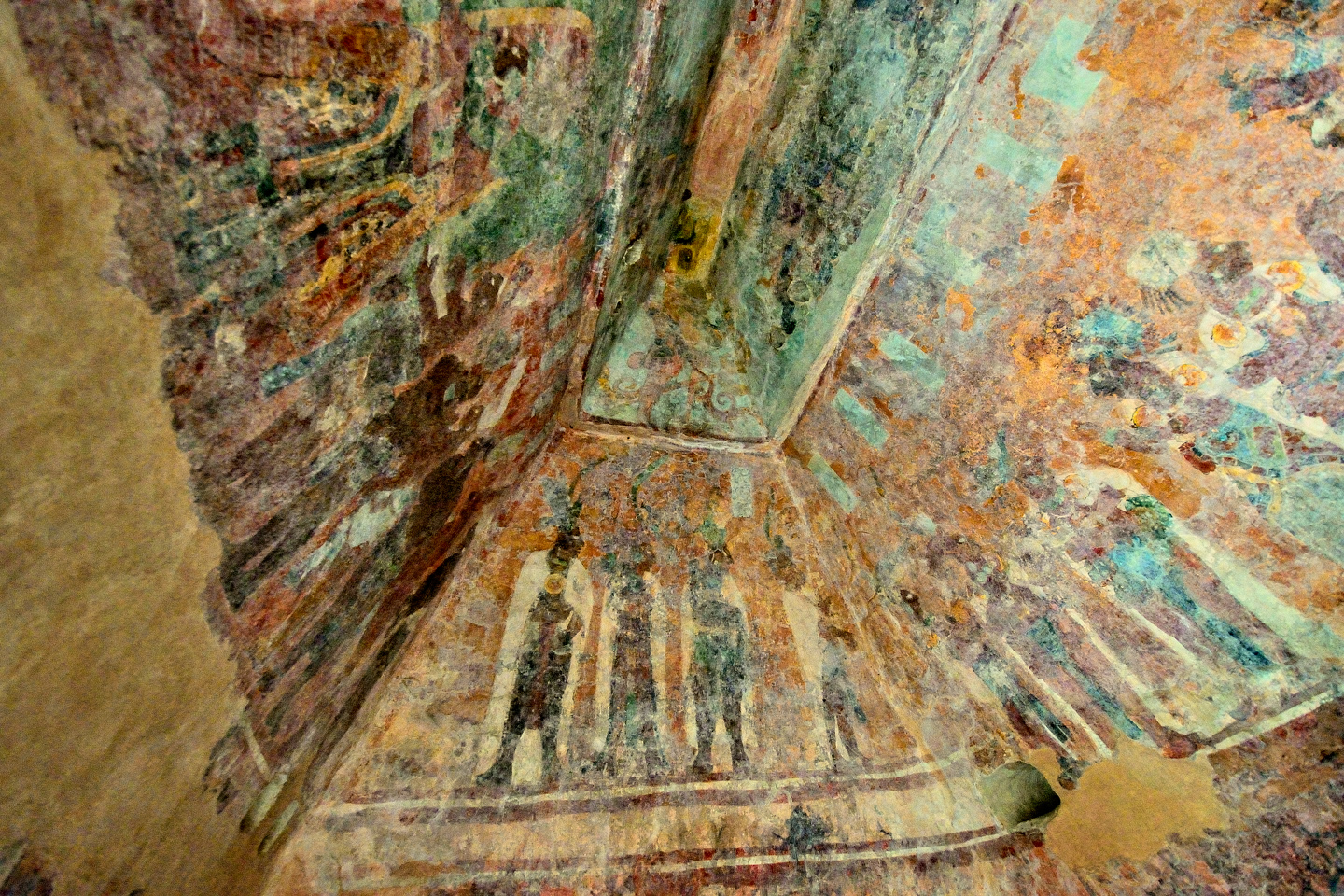

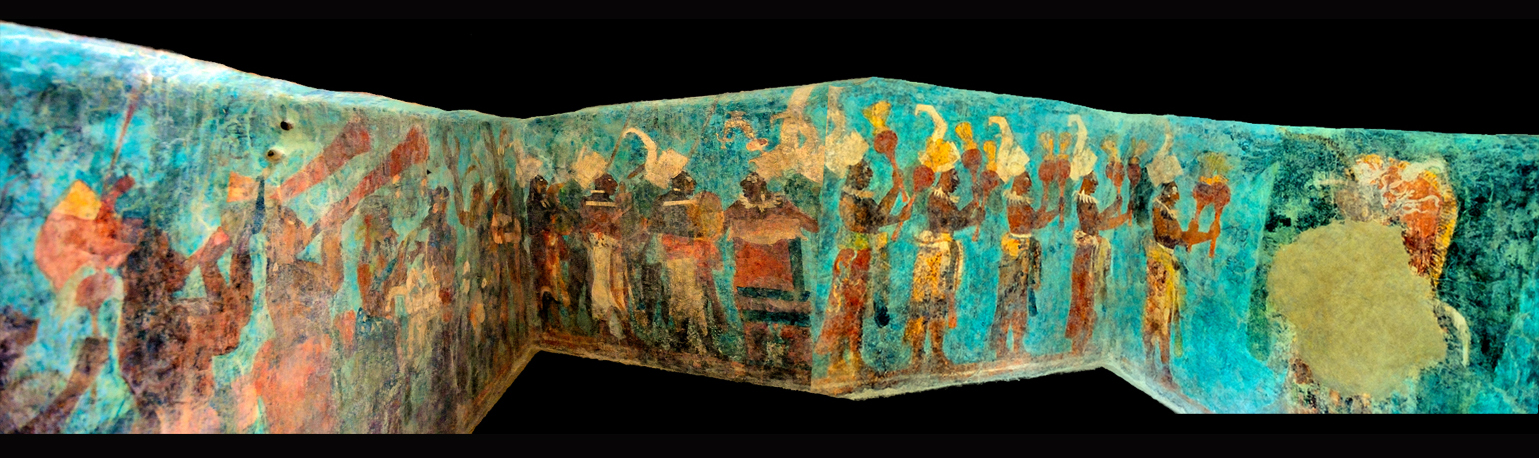

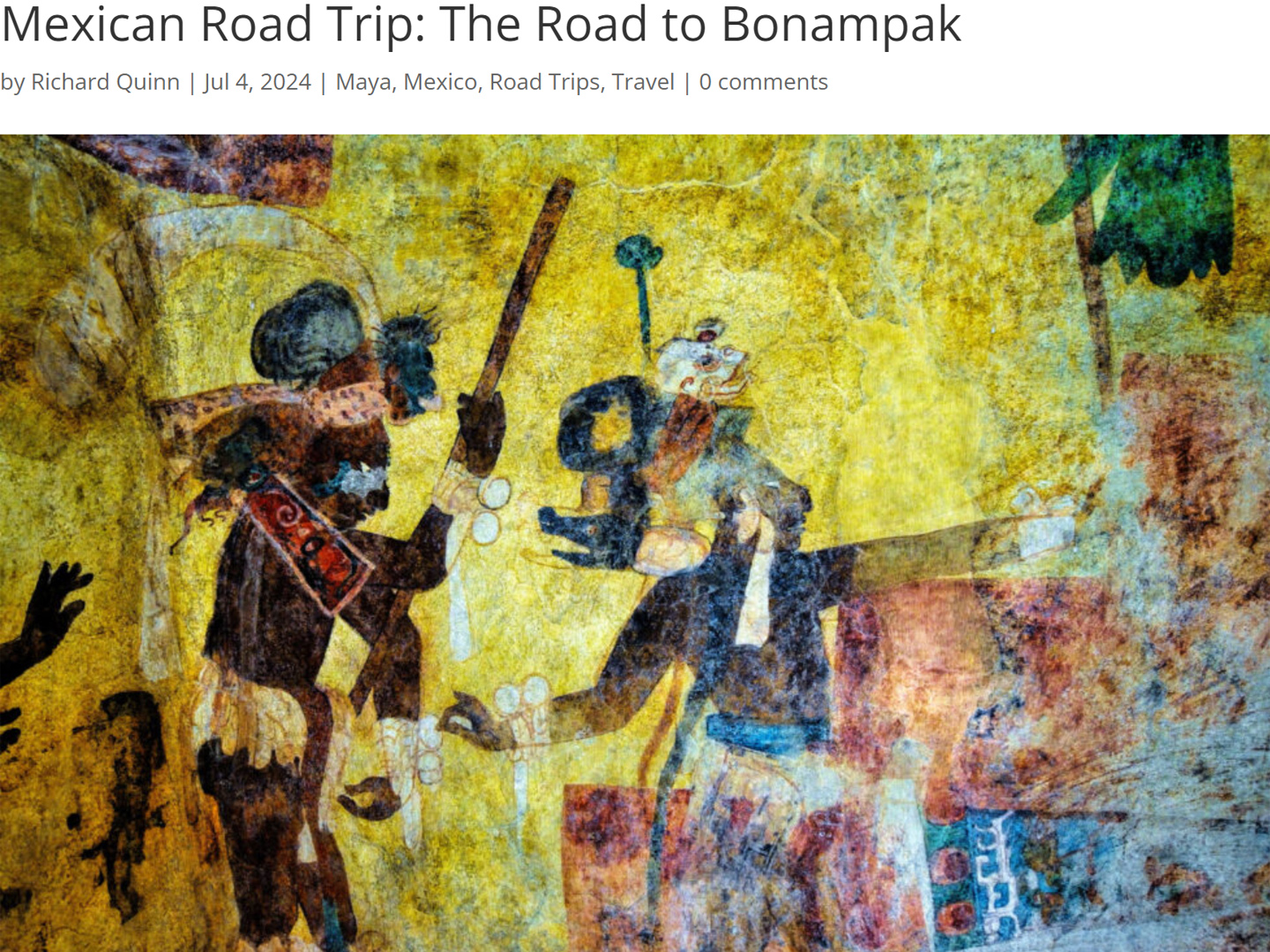

Each of the three rooms was painted, floor to ceiling, with elaborate murals. There are scenes that flow together and wrap around the corners, and hundreds of individual characters. Each room had a different theme: the birth of an heir, victory in battle, sacrifice and celebration. Taken in sequence, the murals tell a story of events that took place 1200 years ago, shortly before the city was abandoned.

Painted murals on the interior walls of temples and palaces were not uncommon in the world of the Maya, but that type of art almost never survives. The pigments degrade, the underlying plaster crumbles, and all that’s generally left are traces, perhaps a swatch of color, or an outline on ancient stucco. Bonampak is the singular exception to this law of the jungle, the one place where Mayan murals have been found largely intact, and the reason why can be traced back to a fundamental principle of chemistry. The debris in the doorways didn’t seal the rooms nearly well enough to protect the paintings from the tropical climate. Quite the opposite: rainwater pooled outside the building and seeped through the limestone walls, thoroughly saturating the murals. As the mineral-laced moisture evaporated, it left the surface of the paintings covered with a sheen of calcite, a hard, translucent glaze. This cycle repeated, over and over, building up layer upon layer of a coating that served to protect the paint and the plaster. If it had been planned that way, it could not have done a better job, with the net result that the murals are still with us, and in surprisingly good condition. In the 1980’s, the Mexican government brought in a team of specialists who spent three years removing the coating, cleaning the paintings, and stabilizing the underlying stucco. The results of those efforts left the murals looking better and brighter than ever, but still fragile, and extremely vulnerable.

Bonampak was never a “lost city.” The temples have always been known to the local Lacandon Maya, who use them for religious purposes, but it wasn’t until 1946, when the villagers showed the murals to an outsider, that the rest of the world became aware of what had been preserved here. Since that time, the paintings have been extensively studied, using advanced techniques like infrared photography and thermal imaging, which brings out latent detail that can’t be seen with the naked eye. As exciting as this might be to a Maya buff like myself, Bonampak is not all that well known to the average tourist, and visitor numbers have always been quite low. On the day Mike and I went there, we had it entirely to ourselves, and because of that, the caretakers graciously allowed us to walk all the way inside each of the rooms, and to take our time when viewing and photographing the murals. When tour groups arrive, and the site gets even slightly crowded, everyone has to line up and wait their turn to view the paintings. No one is allowed to enter the temple, the way Mike and I did. There is a separate queue for each room, and when it’s your turn, you step up to the threshold, and peer in through the doorway. Each visitor is allowed just 20 seconds with each of the three rooms, and I’m told that the limit is strictly enforced. The point is to protect the murals from the moisture in our breath, which is a serious concern.

As a photographer, capturing decent images in that temple was an enormous challenge, even without the restrictive time limit. The only light in those small rooms is what comes in through those small doors. You’re not allowed to bring in any photographic lighting, you’re not allowed to use a flash on your camera, and you’re not allowed to use a tripod. We were fortunate in having clear skies, at least, but those interiors were really quite dim. I set my cameras to a high ISO, used a wide open lens, a slow shutter speed, and I held my breath with each shot. How did I make out? I’ll let you be the judge. Follow along, and I’ll take you on a virtual tour, starting with:

ROOM 1

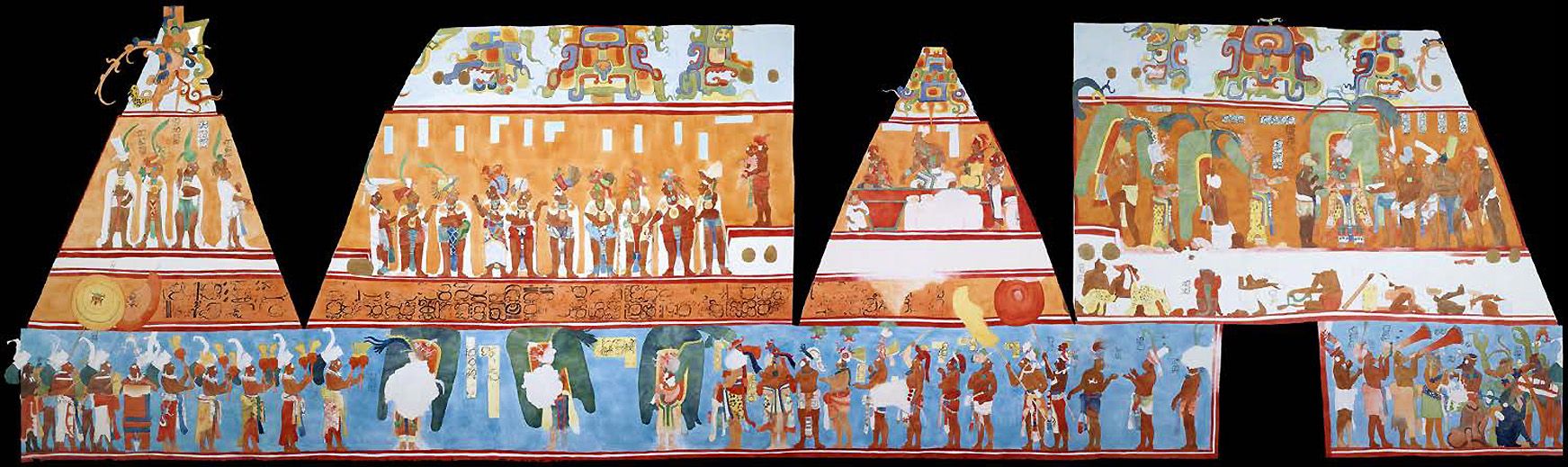

1.) Reproduction of Room One by Latin American Studies.org; 2.) Composite photo of the lower wall

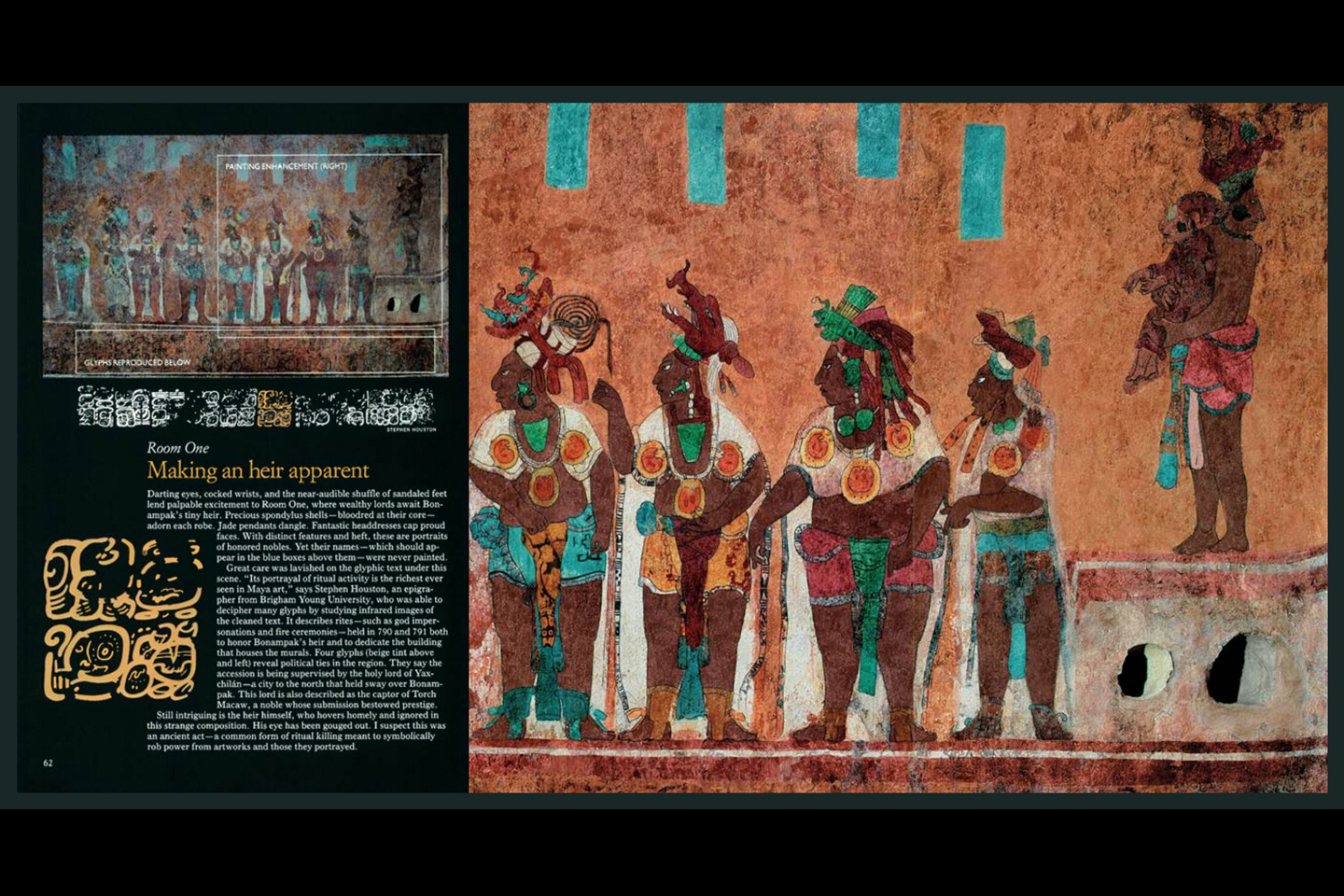

Room 1 is entered through the door on your left as you face the temple, and it is in this room that the remarkable story begins. The paintings travel around the room in four distinct segments, beginning with the panel nearest the floor. We see a procession of lesser nobles, including musicians, and men wearing elaborate god masks, lined up around the walls, against a bright blue background. Above them is a narrow band containing hieroglyphs on one side, and images of captives or menial workers on the other. Next is the widest, most impressive panel, in which we have Chaan Muan II, the Lord of Bonampak, presenting his new son and heir to the nobles of his court. These are clearly important personages, sumptuously dressed, each in a different costume, standing in a line before their ruler; each of the two longer walls features a separate, but similar scene, against an orange background. Finally, the vaulted ceiling, which is filled with designs representing the Mayan version of heaven, and images of gods.

CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND

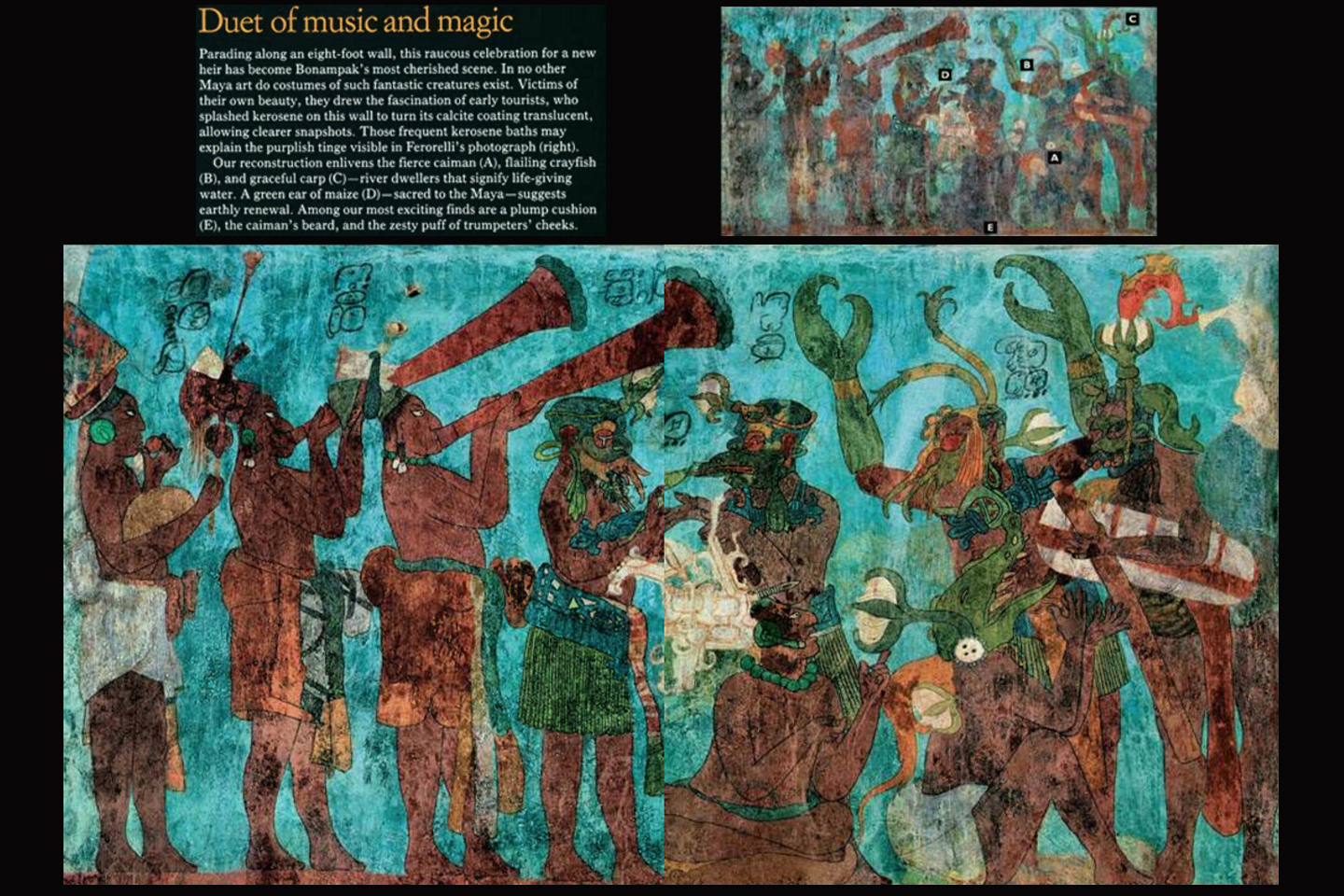

One of the most interesting scenes is a segment of the lower panel featuring musicians and costumed dancers. Early visitors to Bonampak were in the habit of spritzing kerosene on this and many of the other panels to brighten the colors for their photos. By the time anyone realized it was damaging the paintings, it was too late to do anything about it. When the National Geographic Society conducted their study of the murals, they meticulously recreated some of the panels with the additional detail gleaned from high tech photography. The resulting images were published in their magazine in February of 1995.

The Lord of Bonampak presents his heir to the nobles of his court. National Geographic has recreated this scene with extraordinary detail.

Musicians and costumed dancers entertain the court in this famous panel, another of the segments that National Geographic’s experts chose to recreate.

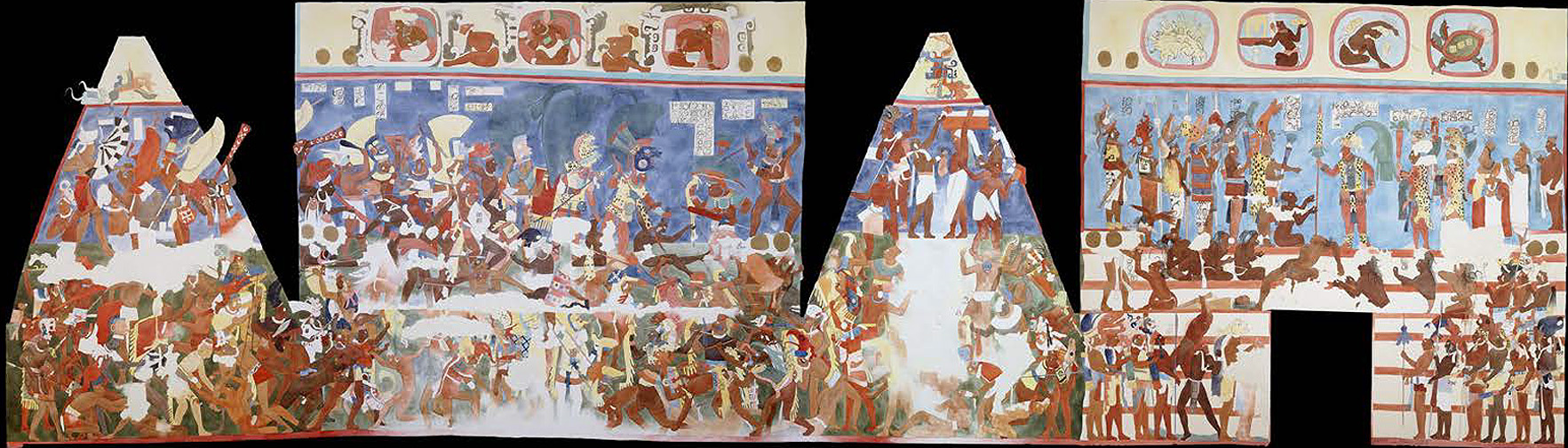

ROOM 2

Reproduction of Room Two by Latin American Studies.org

Room 2 is entered through the door in the center, and presents images that set a much different tone. These are battle scenes, in which the Lords of Bonampak vanquish seemingly helpless villagers for the purpose of taking captives. Captives were the fuel of Mayan society, the energy source that made it work. Slave labor built their monuments, raised their crops, transported their goods, and more. The pool had to be continuously refreshed, because the bloodthirsty Mayan religion required a constant supply of expendable humans to serve as sacrificial offerings to their gods. In one panel, Chaan Muan II, dressed in all his finery, grasps a terrified villager by the hair, as the man struggles desperately to free himself. In another, a row of bound captives sit weeping in pain, their fingertips dripping blood after their nails were ripped out. A corpse lies sprawled in the foreground, a realistic use of perspective. It was this panel, more than any other, that debunked the notion that the Classic Maya were a peaceful people ruled by learned astronomer priests. The Maya nobles depicted here were anything but peaceful.

The details in the murals in Room Two are not as crisp as what you see in the other rooms, but perhaps that’s just as well. These are scenes of violence and cruelty, graphic depictions of the outcome of a one-sided battle, and of the vast divide between the Mayan nobility and the common people. National Geographic’s restoration brings all this to life with startling clarity.

A scene of torture and cruelty as the Lords of Bonampak take prisoners for use as sacrificial victims.

A chilling scene, as a terrified captive struggles in the grip of the Lord of Bonampak.

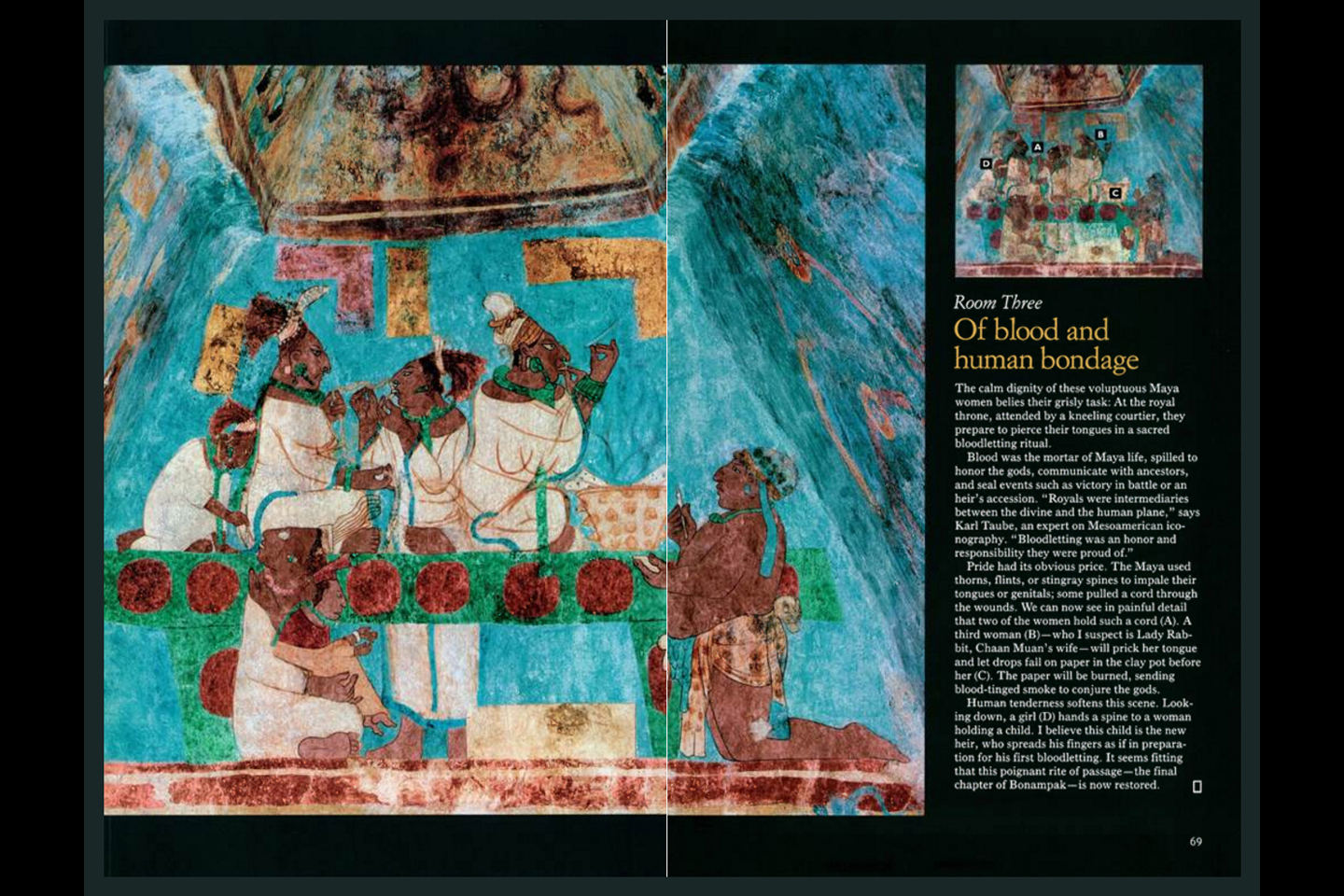

ROOM 3

Last, but certainly not least, is through the door on the right. This is where the prisoners captured during the battles in Room 2 are sacrificed. There are celebrations, with music and dancing and gigantic hats that look like a collaboration between Dr. Seuss and Hieronymus Bosch. One of the upper end panels depicts a particularly graphic scene in which a group of noble women pierce their tongues with stingray barbs to draw blood, as an offering to the gods. The heir to Chaan Muan II, presented to the court by his father in Room 1, is seen here with his mother, preparing to participate in his first bloody sacrifice.

In addition to the damage caused by early visitors and their kerosene, there is other damage to the panels that appears to be vandalism: the faces of some figures have been scraped away, and on others, the eyes have been gouged out.

According to scholars, this was in fact deliberate, but it wasn’t vandalism. Many of these painted characters represent specific individuals who lived in that era. The mutilation of their portrait may have been a way to nullify the power associated with their legacy. Such “de-Facing” of art was not at all uncommon among the Maya; it’s actually thought to predate Mayan culture, as it is a practice that originated with the Olmecs.

A Scene of Blood Sacrifice!

This scene of blood sacrifice is one of the clearest, most interesting images at Bonampak, and National Geographic’s restoration efforts have taken it up a full order of magnitude, revealing even the tiniest details. If slaves were the fuel that powered Mayan society, blood was the fuel that powered their religion. Many Mayan temples were originally painted red, and that’s hardly a coincidence.

It’s almost unimaginable, but artwork such as this must have covered the walls of nearly every important building in the Mayan world, documenting the lives and the fantasies of all their kings in graphic, colorful detail. The Mayan cities as they appear today, pyramids and temples built of weathered limestone, the only color coming from vegetation sprouting in the cracks between the blocks; those ruins bear no more than a passing resemblance to the original constructions that stood on those crumbling foundations. The Maya loved color. The evidence of that is abundantly clear, especially when we look at the Bonampak murals. These places would have truly been something to see, back in their glory days. (As long as you weren’t on the losing side of one of those one-sided battles.)

The caretakers eventually called time on my photo session, so Mike and I explored the rest of the site, very little of which has been cleared and opened to the public. There were several interesting sculptures, and two of the stelae ranked among the best I’d seen anywhere, tack sharp detail chiseled into the stone. One of those, at almost 20 feet in height, is among the tallest that have ever been found, anywhere in the Mayan world. The rest of it, the pyramids and temples, were a bit anticlimactic after the splendor of the Amazing Murals.

CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND

CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND

We only stayed at the site for about an hour and a half, but after we’d maxed out the time we were allowed to spend with the murals, there wasn’t much point to hanging around. It wasn’t all that late in the day. Not yet, anyway, but after all the explicit warnings about traveling MX 307 in the dark, we were anxious to get going. We thanked the caretakers for their kindness, and said our farewells, then made that long walk back to the parking area. The van that brought us from the highway was there waiting for us, and in what seemed like no time at all, we were back at my Jeep, safe and sound.

A FAST RUN BACK TO PALENQUE!

Ruta Maya Road Sign, complete with its own Tope

We knew what to expect on the drive back. Our old friend MX 307, only this time we’d be traveling in the opposite direction. We had enough time, so there was no real reason to be nervous, but even with the familiar road and no pressure, I had this niggling sense of dread, almost like we were being watched. Considering the lawless reputation of the area, even back in 2015, it’s entirely possible that we were! Even so, I had no regrets about having come down there. Bonampak, our 14th (and last) Mayan ruin, was the one site that finally put a human face on the people who built all of this amazing stuff.

We came to the downed tree, still blocking the road (this time on our side of the highway)…

…and another group of schoolkids who looked like they were waiting for a ride.

In some areas, the road was like a tunnel through the trees.

As always in rural Mexido, we saw plenty of “Non-traditional” transportation!

Scenes from our return journey along MX 307

With Mike doing the driving on the way back, I was free to use my still camera to catch a few scenes along the road, in sharper focus. Like their Mayan ancestors, native people in this area are lovers of color. Beyond the more populated areas there were farms, rural homesteads, and verdant pastures, with horses and cattle grazing. It was a bucolic, incredibly peaceful scene, which made it hard to reconcile with everything we’d been hearing about trouble from smugglers and criminal gangs.

We made it back to Palenque well before sunset, and headed straight to the Hotel Chablis for a couple of cold ones, and a little route planning. The first time we were in Palenque, we tried to drive to San Cristobal de las Casas, a charming colonial city on the other side of the Sierra Madre. Not only did we underestimate the time required, we also ran into that Zapatista road block in Ocosingo, and were forced to turn around. Tomorrow, we were going to try that drive again. The road was notoriously slow and dangerous, so we were looking forward to it! (Ha!)

Next up: Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands to San Cristobal de Las Casas

The collage below features additional photos taken on the road in Mexico by my inestimable shotgun rider, Michael Fritz. (Michael is responsible for many of the photos in this series of posts). Click any image to expand them to full screen:

(Unless otherwise noted, all other images are my (or Michael’s) original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen

Michael Fritz, “Elmo,” 1949-2025

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn't huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we're left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it's 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

As we drove away from the toll plaza, a State Police car that had been parked off to one side made a fast U-Turn and started following me. A moment later, he turned on his flashers and gave me a short blast on his siren, motioning for me to pull over. Two uniformed policemen got out, and approached me on the driver's side. One of them hung back, apparently checking out my license plate before making a phone call.

"Documentos," said the officer by my window. "Licensia, los permisos, seguros, todo eso."

I wasn't sure if I was being stopped for some infraction, or if these guys were just fishing...

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in May, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in May, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer's Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

This series of posts is dedicated to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Michael passed away in February of 2025, after 75 years of a life well-lived. He was unique, and he'll be missed.

Michael Fritz ("Elmo") 1949-2025

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

In 1975, my family of 6 on our annual Summer Vacation to Mexico and included our road trip/hiking trip to Bonampak. I was 16. We hired a local guide in Palenque to make sure we got there as there wasn’t an all weather road. “Rafael” was sure our rig could make the trip. (Our rig was a 19 1/2 ft Class C motorhome.) 11 miles off of the main road, the rains came, making the road completely impassable. The following morning, with Rafael to guide us, we headed off on foot for the hour and a half hike, time to view the site, and our walk back to the motorhome hoping all the day for good weather so that the road would be passable. Rafael got us lost. We did finally make it to Bonampak at dusk. The caretakers fed us and allowed us shelter in the hut that the Archaeologists use when they visited the site. We checked out Temple one, could not use flash, or even a flashlight. It was difficult to make out the murals, but still very cool! We arrived back at our motorhome after dark and were very glad to be there. The road was impassable as it had rained again. The place where we had stopped the motorhome was a clearing. The local chief invited us to eat at his home where we struck a deal with the men of his village to help us get the motorhome out to the main road. In the morning the men cut down three long vines and lashed them to our bumper. Those 11 miles to the main road took us 8 days to reach with varying numbers of men each day. At one point we had 35 men and 4 horses pulling the motorhome. When the distance of the walk back home for the men got too far, we had to contract with the chief of next village. My dad paid the men everyday, and we fed them lunch if they wanted to try our food. It was a fantastic experience for sure. Reading your article brought it all back to me! Thank you!

What a great story–and what an adventure! That’s the kind of thing that could only happen in Mexico. Thank you so much for sharing!