DAY 13: All Roads Lead to COBÁ!

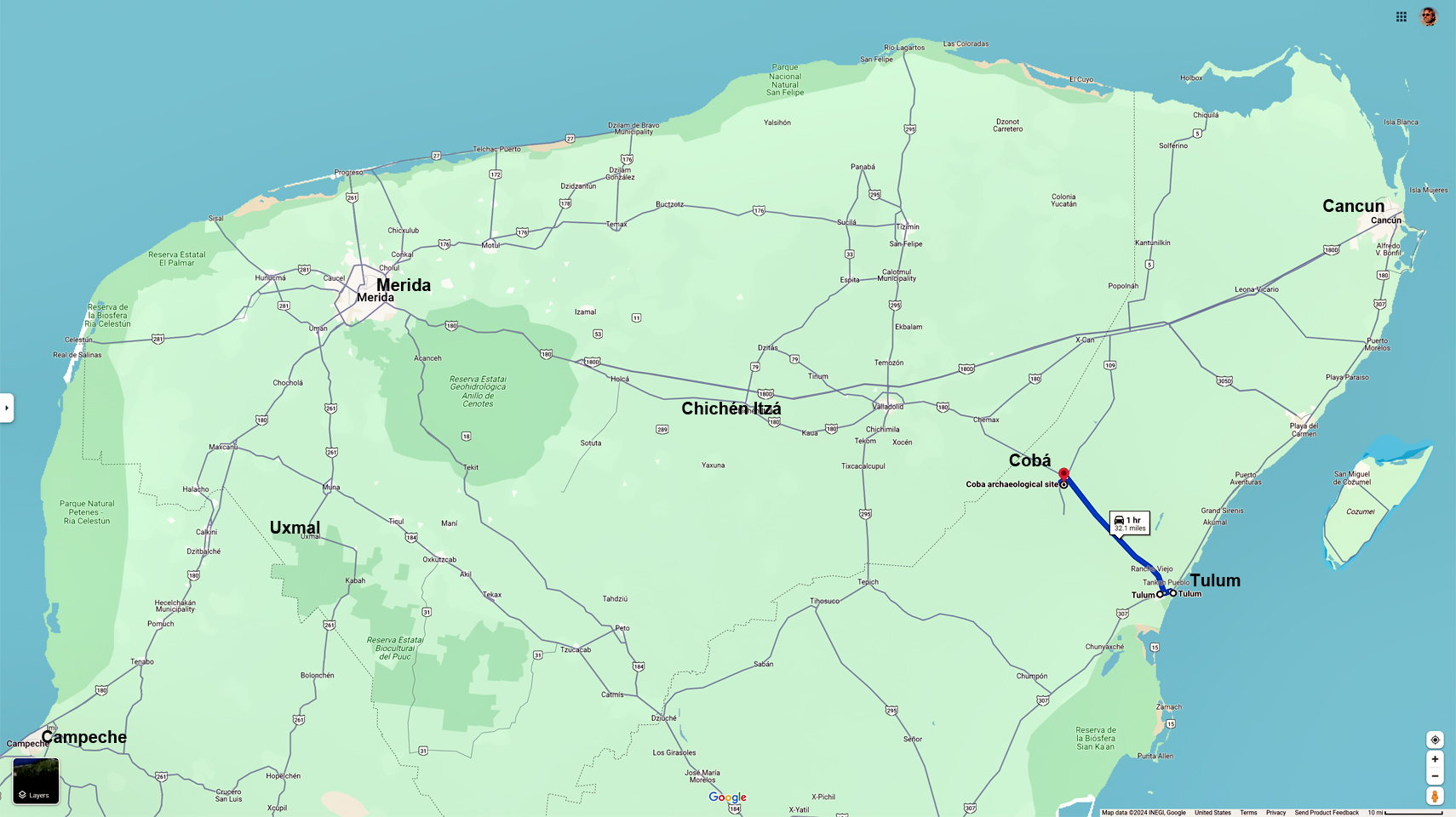

On the 13th day of our road trip, we spent the morning making a follow-up visit to the Mayan ruins at Tulum. (See my previous post: Mexican Road Trip: Cancun, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya). As for the afternoon, our plan called for a visit to Cobá, a large Mayan site just 30 miles away to the northwest. Known as the City of the White Roads, Cobá is the fifth most popular Mayan ruin in Mexico, at least in terms of visitor numbers–although I was fairly sure that had more to do with the proximity to Cancun than it did with the quality of the architecture.

We’d already booked a second night at the Maison Tulum; (with that French bakery on the ground floor, we were certainly in no hurry to leave). That left the rest of the day free, giving us plenty of time to drive to Cobá, explore the ruins, and still make it back to Tulum in time for dinner.

The route couldn’t have been simpler: a straight shot on MX 109, a Quintana Roo State Highway. That meant we’d be contending with potholes, livestock, and the ubiquitous topes (killer speed bumps) but at this point, all that was par for the course.

Street View of Hotel Maison Tulum.

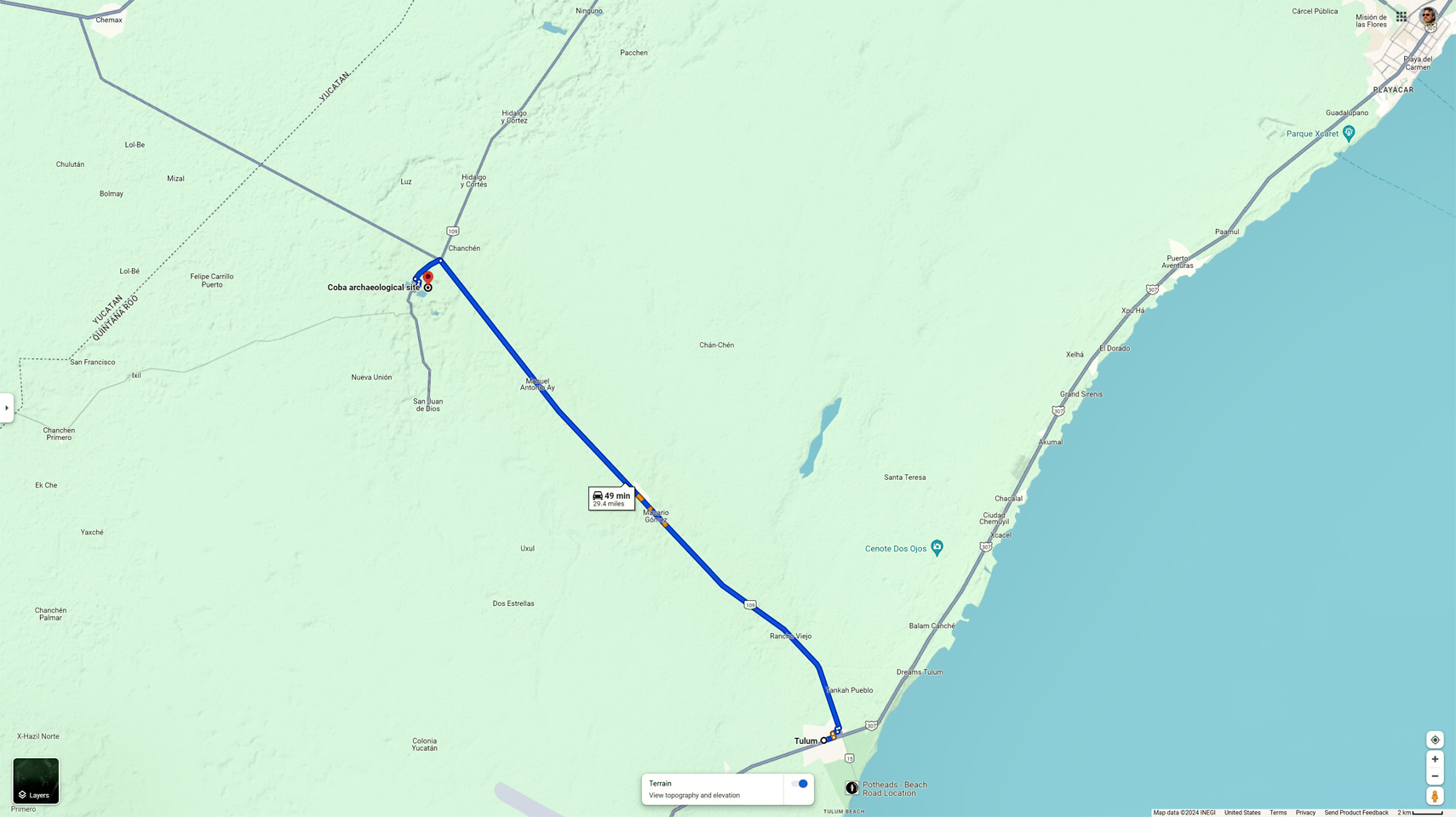

The route from Tulum to Cobá.

Transit Policemen, rolled up beside us at a stop sign.

Coba to the left, Chichen Itza to the right.

COBÁ

We arrived at the archaeological park a little after 1:00 PM. There’s a village adjacent to the ruins, but very little infrastructure in the park itself. A row of tour buses sat idling on one side of the lot, engines running to keep their AC going, but there were no more than a dozen private cars in view, and some of those probably belonged to staff. This was October, the off season, but I got the sense that the lack of private cars was typical, that the majority of Cobá’s visitors tend to come on those buses, not on their own.

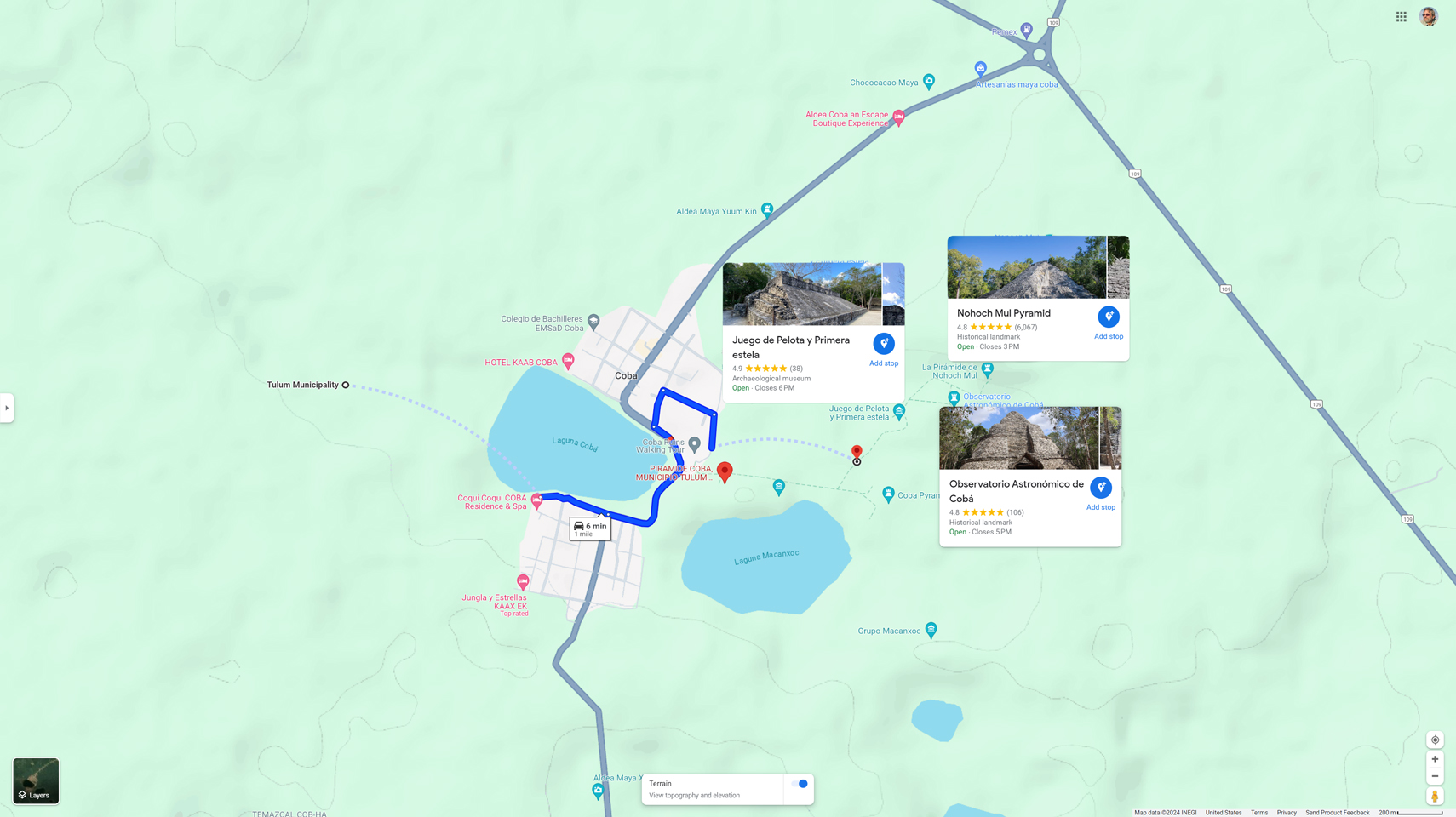

The ruins of Cobá © Google Maps

The ruins of Cobá: Park Entrance

The ruins of Cobá: Google Satellite View

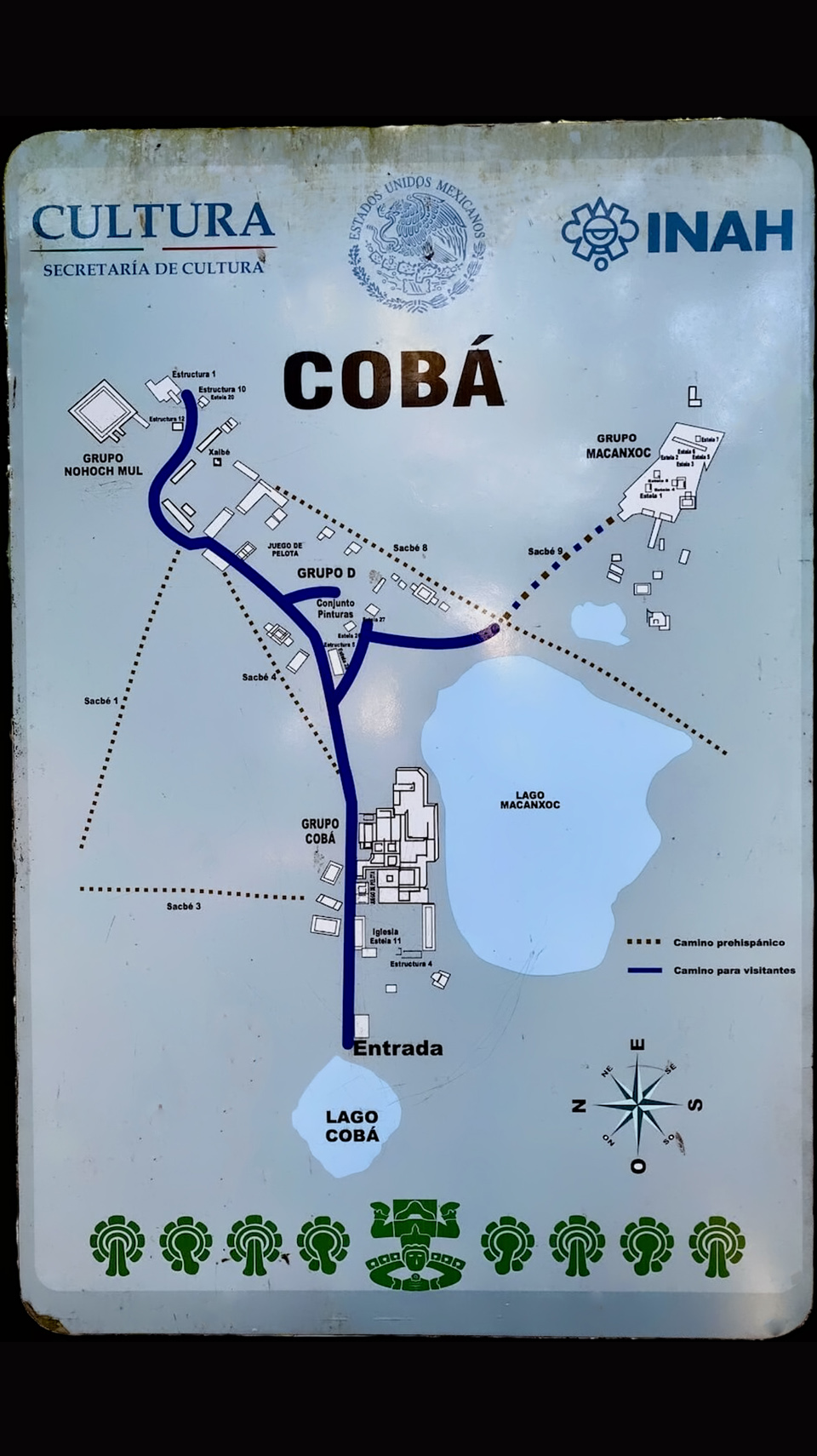

The first thing we saw when we walked in was a bicycle rental concession, along with a fleet of pedicabs, all staged near the entrance, and doing a booming business. We rather quickly found out why. In it’s day, Cobá was one of the largest of all Mayan cities, with a population estimated to have been more than 50,000 people, spread out over several square miles. Unlike the other sites we’d visited, there wasn’t one central area where all the most interesting structures were clustered.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

The attractions at Cobá were spread out, just like the original old city had been, so there were actually four different groups of ancient buildings, separated by as much as two miles! On the plus side, the old Mayan roads, the sacbeob, still connected the various sections, and portions of them are kept in good enough shape to use as bike paths.

Many of the people we saw returning their bikes after finishing their tour looked like they’d just run a triathlon, puffing and panting, dripping sweat, and red in the face–which was hardly an endorsement of the experience. October in the tropics can still be quite warm. With all the rain, the day was humid to the point of stifling, and the path was lined by thick jungle growth that blocked off any hope of a breeze. Honestly? Mike and I didn’t even ask about the bicycle rentals. We went straight to the Pedicab stand, and sat ourselves down in the first available. Our designated pedaler was a young guy named Francisco, who was clearly in better shape than either of us old gringos. He offered us a two hour circuit of the ruins for 200 Pesos (a little over $10). Sounded downright cheap to me, so off we went!

Cobá is so spread out, most visitors rent bicycles; me and Mike chose the Pedicab option; (hence, Mike’s toothsome smile).

Francisco was quick to point out that he wasn’t a guide. Official guides had to be certified, and it wasn’t so easy to get that credential. He would nevertheless do his best to answer any questions we might have, and he’d let us know what we were seeing as we made our way through the site.

The first stop, not far from the entrance, was a Ball Court, with sloping sides, and stone goal rings still in place. Every Mayan city had at least one of these; according to Francisco, Cobá had two of them. This was the smaller court, probably used for practice, or more intimate contests. Players on opposing teams tried to knock a rubber ball through the goal without using their hands or feet.

Ball Court #1, flanked by a platform with stone steps. The game was a merger of sport, politics, and religion. In some contests, the losing team was sacrificed to the gods!

Cobá was quite a big deal back in its heyday, from 600 AD to about 1000 AD. Being the largest city in the area gave them the resources to dominate their neighbors, and that’s exactly what they did. They demanded tribute from all the lesser Lords, and secured their privileged position by forging close alliances with their most powerful rivals, the kings of Tikal, Dzibanche, and Calakmul. It’s quite probable that they secured those ties through intermarriage of the noble houses. Based on inscriptions found on many of the stelae at the site, a great many of the rulers of Cobá are thought to have been women. It’s important to note that even though major new construction ceased after 900 AD, Cobá was not abandoned at that time. The city remained occupied, and the original structures were still being maintained well into the 14th century, almost up to the time of the Spanish Conquest. When Chichén Itzá started its rise to prominence, Cobá was already beginning its slow decline, yet it remained a force in competition with the mighty Itzá for at least a century.

Cobá was a religious center, with the largest, finest pyramids and temples in the area, and it was also at the center of a thriving trade network. The Maya never quite developed the wheel, and they had no draft animals, so everything that required transport had to be carried on the backs of humans. The sacbeob, the White Roads, were raised pathways that spread out from Cobá’s ceremonial and administrative centers like a web. The name came from the layer of crushed white stone spread along the path to reflect moonlight, making it easier for the bearers to move their loads in the cool of the night. Within the city, the sacbeob connected hundreds of residential clusters, each cluster consisting of fifteen houses built atop a raised platform. Outside the city, the White Roads extended for as much as 100 km, connecting the many smaller Mayan cities and towns that traded with Cobá, and owed fealty to the kuhul ajaw, their divine ruler.

The thought that we were rolling along those original sacbeob was very cool; there were more of them in evidence here than at any other site in the Mayan world. The crushed white stone that once defined the pathways is long gone, but since the park closes at 5:00, the only people who might benefit from reflected moonlight are people who–let’s face it–shouldn’t be out there in the first place.

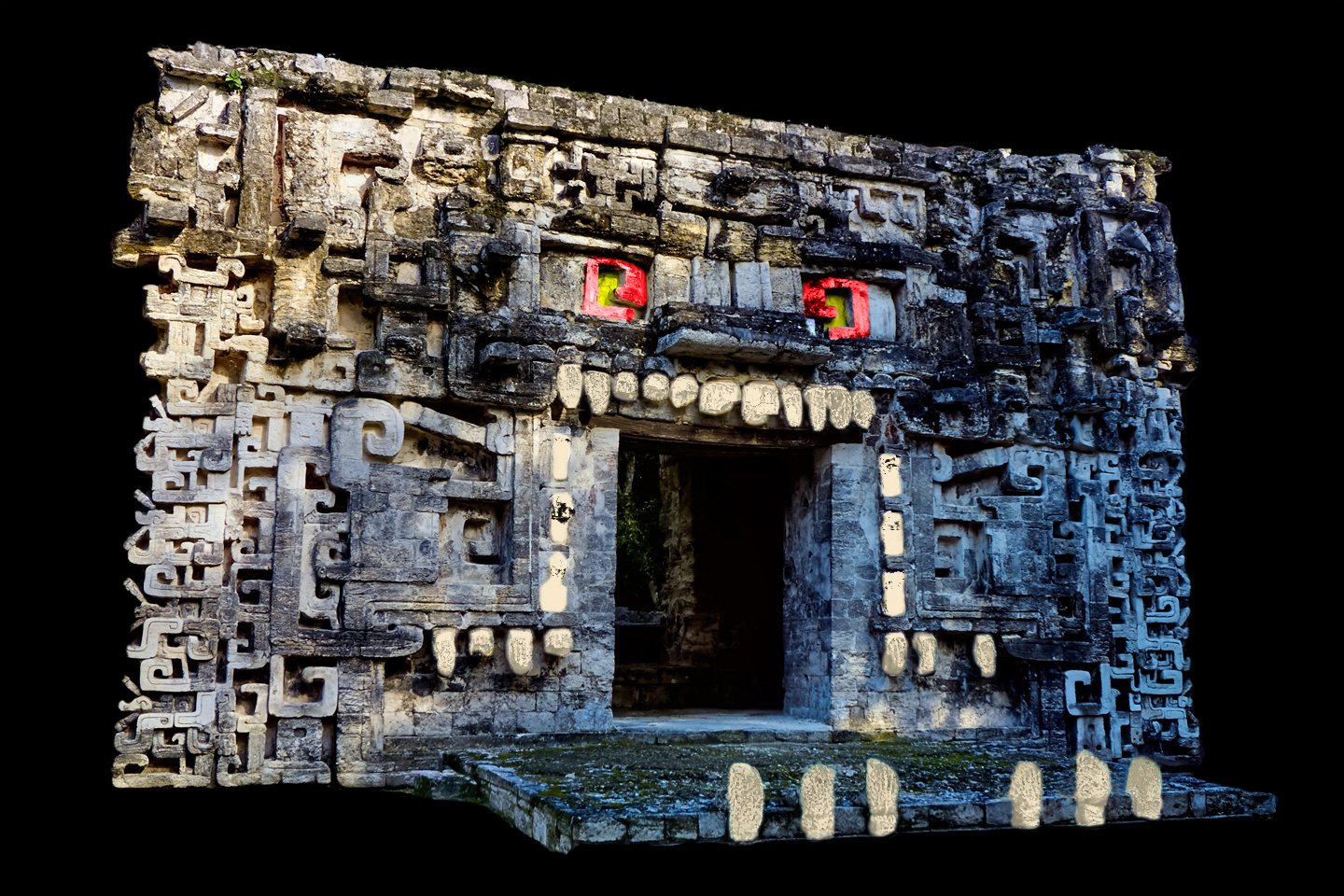

The Pyramid of the Painted Lintel, with a staircase up one side. Climbing is not allowed, so the close view of the painted stones was taken with a telephoto lens.

We pedaled along for 20 minutes or so, then got out and walked to the next major grouping of structures, centered around a squat, truncated pyramid topped by a blocky temple. This was the “Pyramid of the Painted Lintel,” so called because of the stones above the temple doorway that are still coated with the original red and blue-green paint. The temple and its lintel was protected by a palm thatch roof supported by wooden poles. According to Francisco, the roof was a recent addition, put there to shield the ancient paint from direct exposure to the weather.

The painted lintel is a rare surviving example of the original paint that once decorated most Mayan temples.

Francisco was well accustomed to the task of pedaling visitors around the ruins, but this particular day was extra humid from all the recent rain, and we were on a section of path that went slightly uphill. The poor guy was struggling, standing up on the pedals to put all of his weight into the down strokes, and sweating buckets. I insisted that he pull over and take a break while we explored the next set of ruins on foot.

The architecture was classic Peten style, influenced by the early Mayan city-states in northern Guatemala. The structures are old and worn, blocky, lacking the flair and the artfully restored embellishments that characterize the more famous sites, like Chichén Itzá and Uxmal.

Cobá wasn’t opened up to tourists until the 1980’s; only a small part of the old city has been cleared.

Much of what was originally cleared is already overgrown again, with jungle trees sprouting from the steps and platforms.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

A short distance away was the main Ball Court, which was definitely bigger than the first one. There were carved stone panels and other sculptures, including a stone skull, very worn, mounted flush with the ground at the center of the court. Most interesting was a large panel of glyphs, a record of dates and other details relevant to the contests that took place here. One of the two goal rings has a section broken out, which is actually typical. They’ve found at least a hundred Mayan Ball Courts in the Yucatan, and only a handful had goal rings still in one piece. At some Mayan sites, broken rings have been replaced with intact replicas. Here, they did no such thing.

Just beyond the main Ball Court was a four-tiered conical structure known as the Xai’be Pyramid, often called the Iglesia (the church). Round buildings are unusual in the Mayan world, and are often associated with the observation of celestial events, and the forecasting of solstices and other seasonal phenomena. The Xai’be Pyramid was thought by some to have served that purpose, in the manner of the famous Caracol at Chichén Itzá, but, according to the archaeologists, no evidence has been found that would back that theory. As far as we know, Cobá’s Iglesia was never anything more than a monument to a ruler’s ego.

The Xai’be Pyramid, also known as the Iglesia (the church)

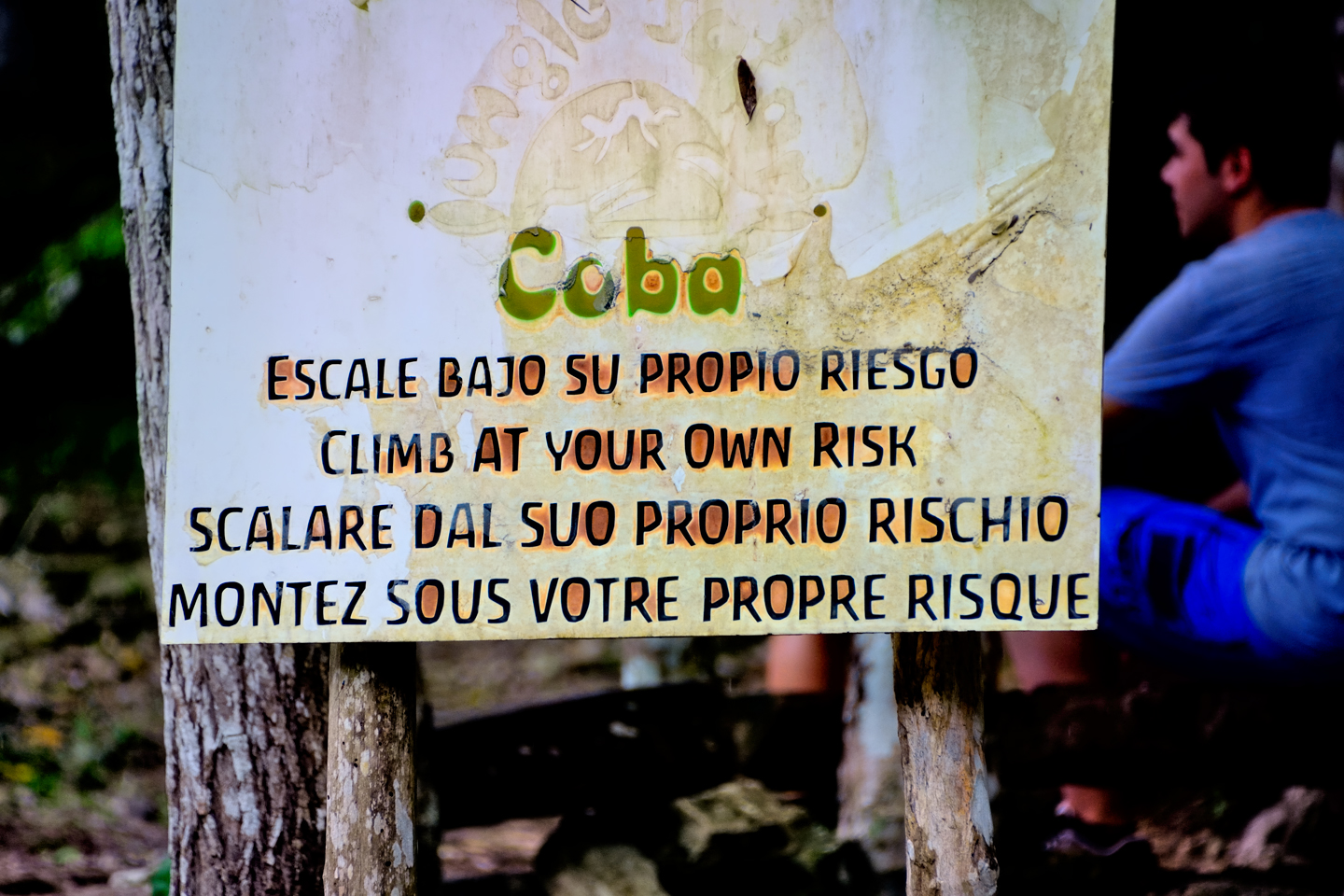

A stone’s throw from the Iglesia was the Ixmoja Pyramid, the largest building in Cobá. Rising 140 feet from its base, the Ixmoja is the second tallest pyramid in the entire Mayan world, and it’s the main reason why most visitors come to Cobá in the first place. Why is it so popular? Because they still allow visitors to climb the darned thing, 130 very steep steps, all the way to the top, where you’re rewarded with a killer view of the surrounding countryside. Pyramids at most of the Mayan sites in Mexico, including the famous Castillo at Chichén Itzá, have been off limits to visitors for decades, for safety reasons, as well as to protect the monuments from the wear and tear caused by millions of trampling feet. If “climbing a Mayan pyramid” is an item on your bucket list, Cobá is one of the very few places where you can still scratch that itch.

Why do I not have pictures from the top? Because, I regret to say, we didn’t make the climb. We stood there and watched for a bit, but in the end, we elected to skip it. When you get to a certain age, you have to be honest with yourself about your limitations, and about the fragility of old bones. My sense of balance isn’t what it used to be; I get dizzy on ladders, and even worse when looking down from high places. I imagined myself clambering up (and then back down again) all of those steep stone steps, climbing in a conga line with all those other people, and, if I’m being honest? It really didn’t look like fun.

Visitors to Cobá, climbing the Ixmoja pyramid.

A warning sign states “Climb at your own risk,” in Spanish, English, Italian, and French.

There is a guide rope fixed in place, the one and only concession to visitor safety. A fall from the top could be fatal!

Cobá is known for its stelae, the flat standing stones carved with intricate designs commemorating important persons and events. The glyphs on the stelae, to the extent that they are still legible, tell the story of Cobá’s noble houses, the wars, the alliances, and the succession of rulers (the cabbages and the kings), complete with dates that they’ve been able to translate. There are several groups of stelae in different sections of the ruins, protected from the weather by rustic palm thatch roofs. To the untrained eye, most of them don’t look like much, but for the Maya scholars, they speak volumes.

↓↓CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND↓↓

There was still a lot more to see, including a large set of buildings known as the Macanxoc Group, but that would have meant pushing our Pedicab driver well beyond the two hours we’d agreed to. The poor guy was pretty well whipped, and Mike and I had put in quite a long day ourselves, so we called a halt. We thanked Francisco for his services, and threw in an extra 200 Pesos as a well-deserved tip.

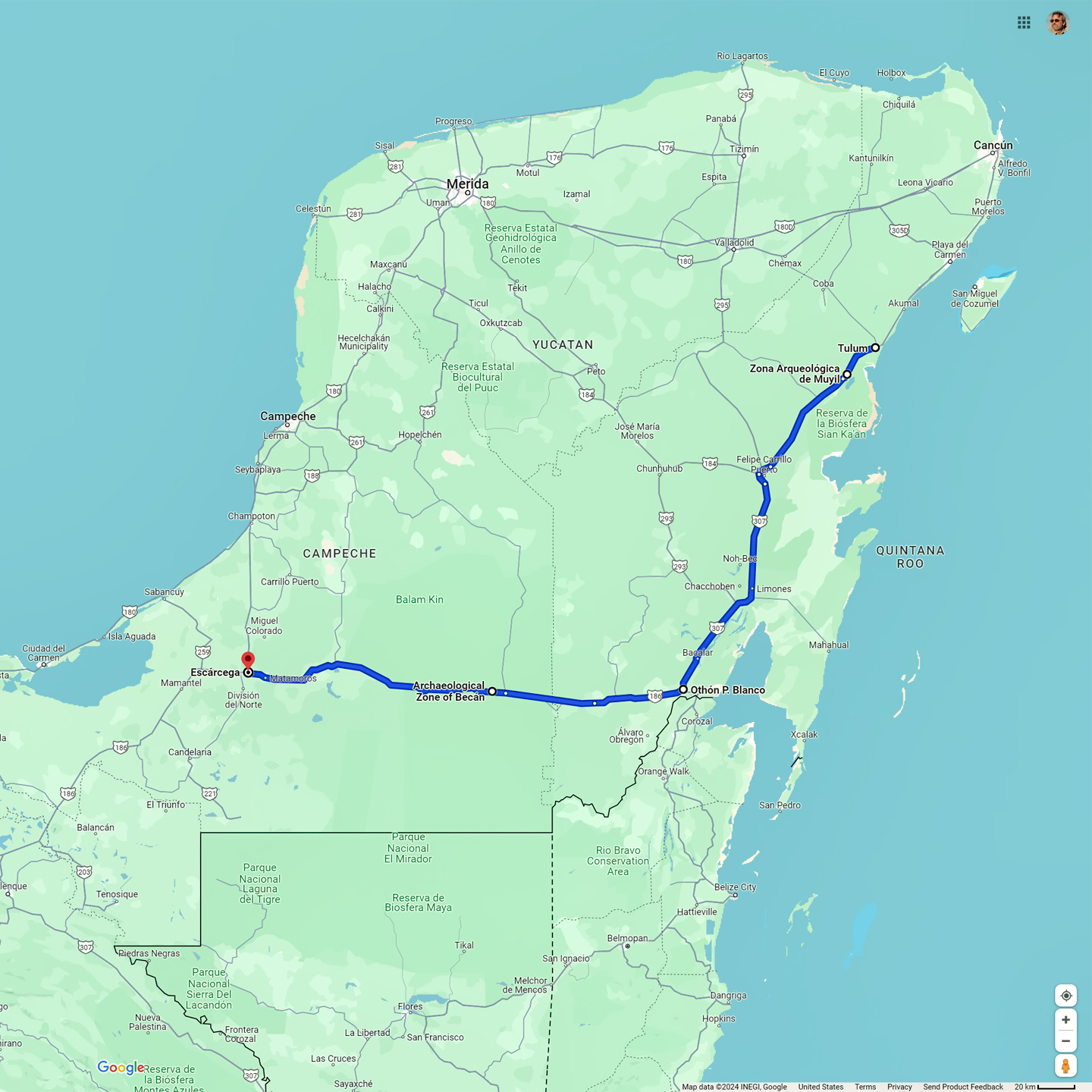

The drive back to Tulum was uneventful (just the way we like it), and in what seemed like no time at all, we were back at our hotel, sipping on a cold brew. After dinner, we spent a pleasant evening in our room, plotting our next move. We were close to the mid-point of our expedition to the Yucatan. We’d been to Palenque, Uxmal, Chichén Itzá, Tulum, and now, Cobá. That was the whole top five, so it was time to shift gears, and start exploring some of the sites that are less well known. With dozens of possibilities to choose from, narrowing down the list was a challenge.

We definitely wanted to go back to Campeche. We’d passed through it much too quickly when we were on our way to Merida the week before, and I’d promised myself a closer look at the place before we left the area. With that in mind, we spread out our maps, and plotted a route from the Riviera Maya to the opposite side of the peninsula, by way of Escárcega. That would not only complete our circle around the Yucatan, it would give us easy access to at least a half dozen Mayan cities that we’d be passing along the way.

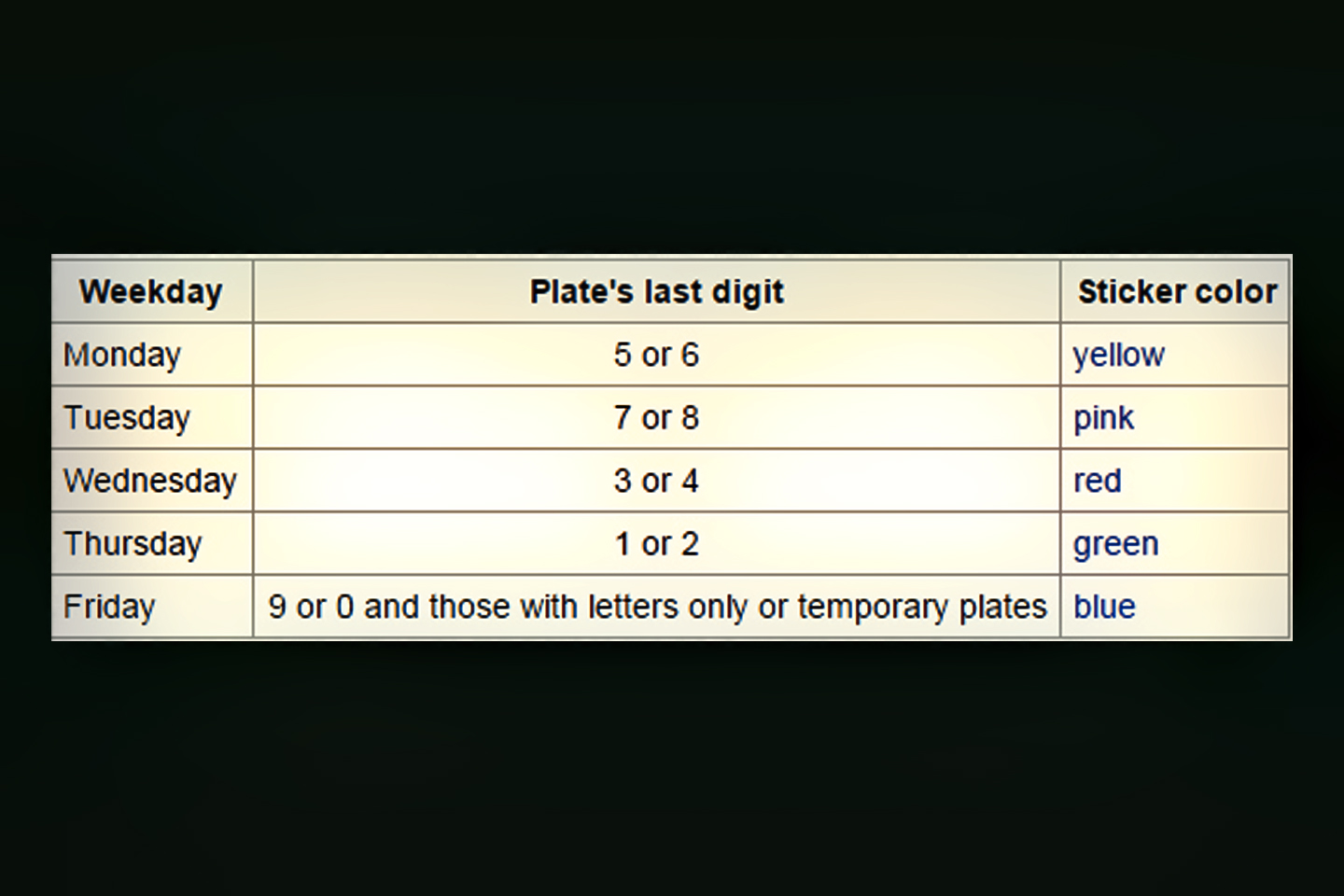

DAY 14: From Tulum to Escárcega, via Muyil, Becán, and Chicanná

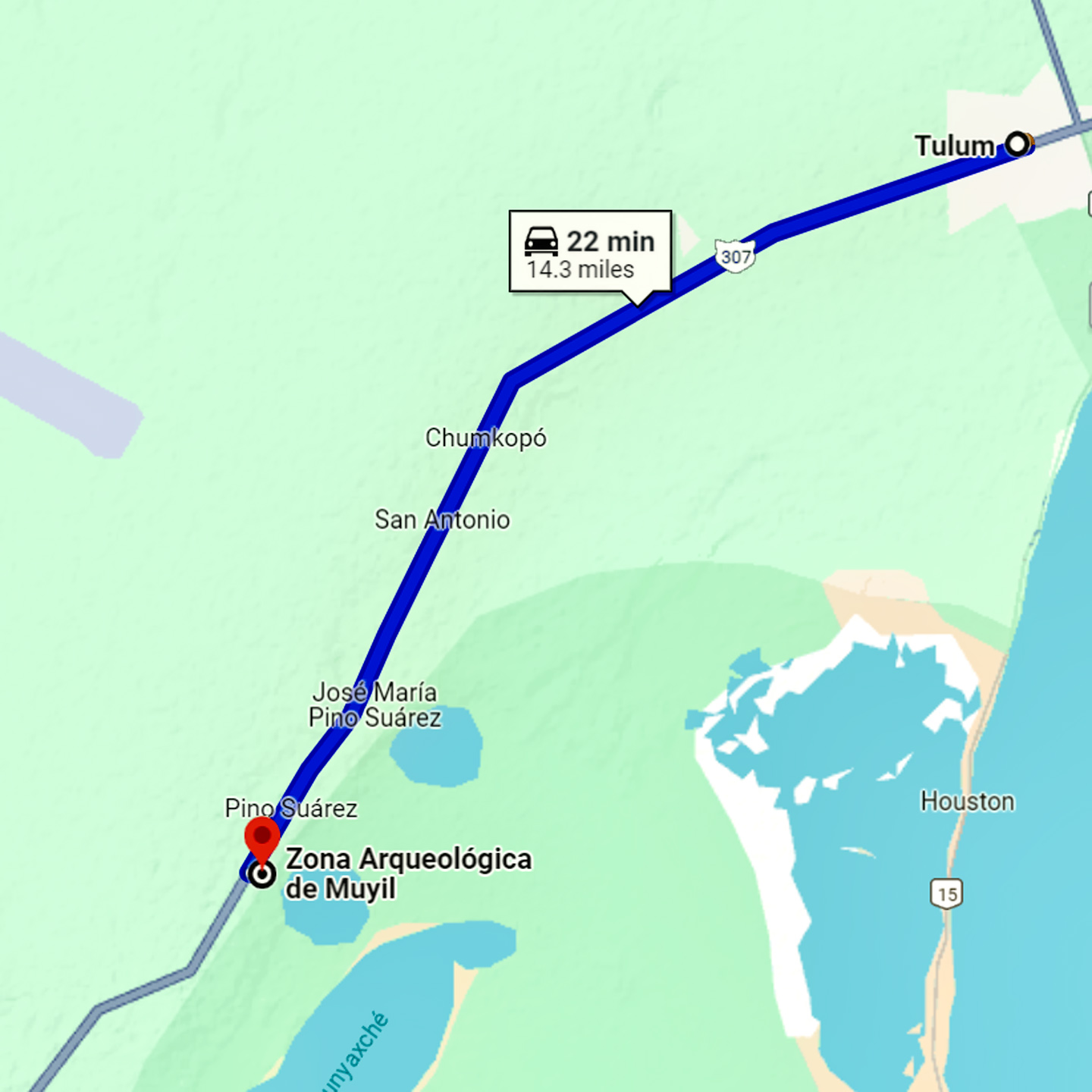

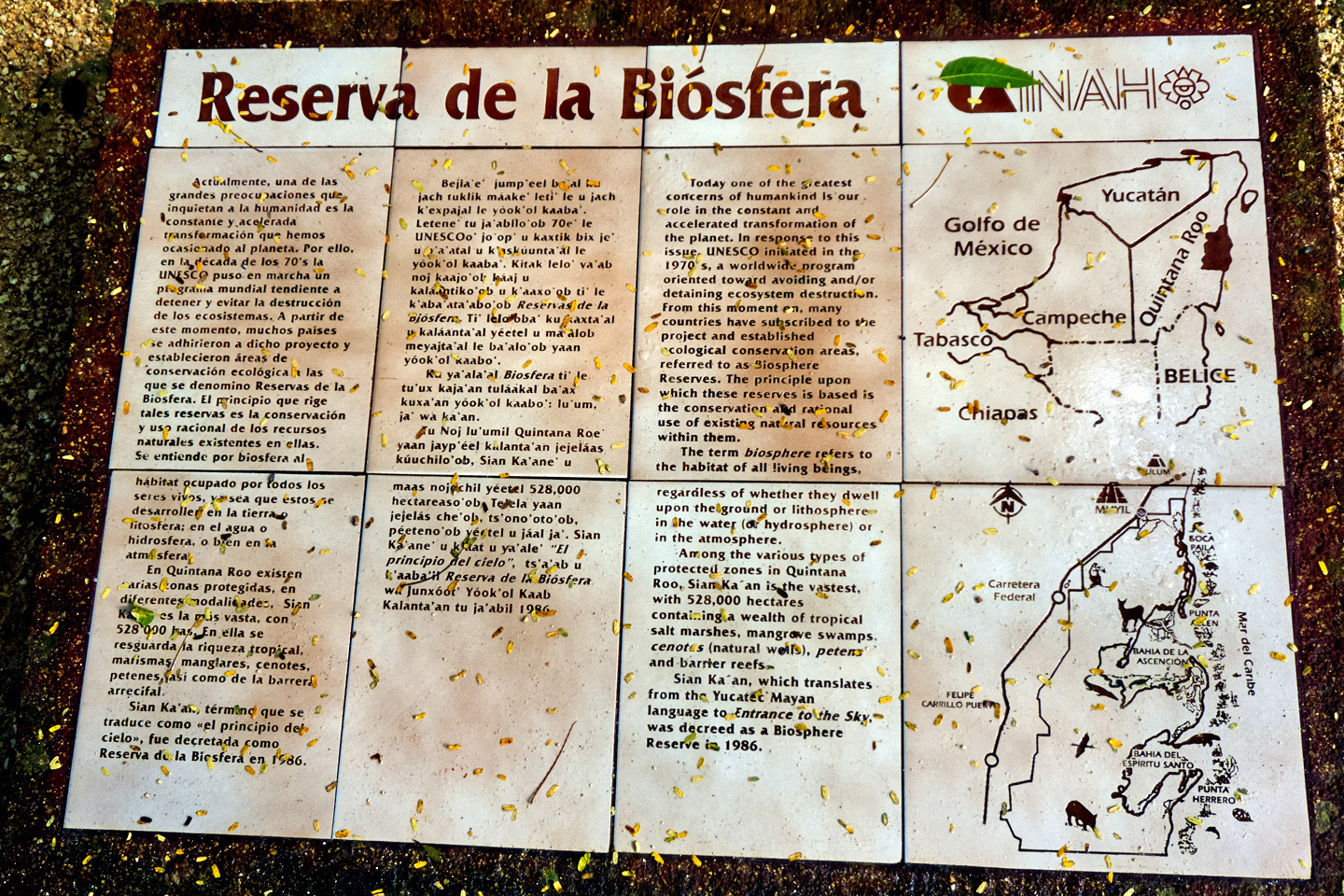

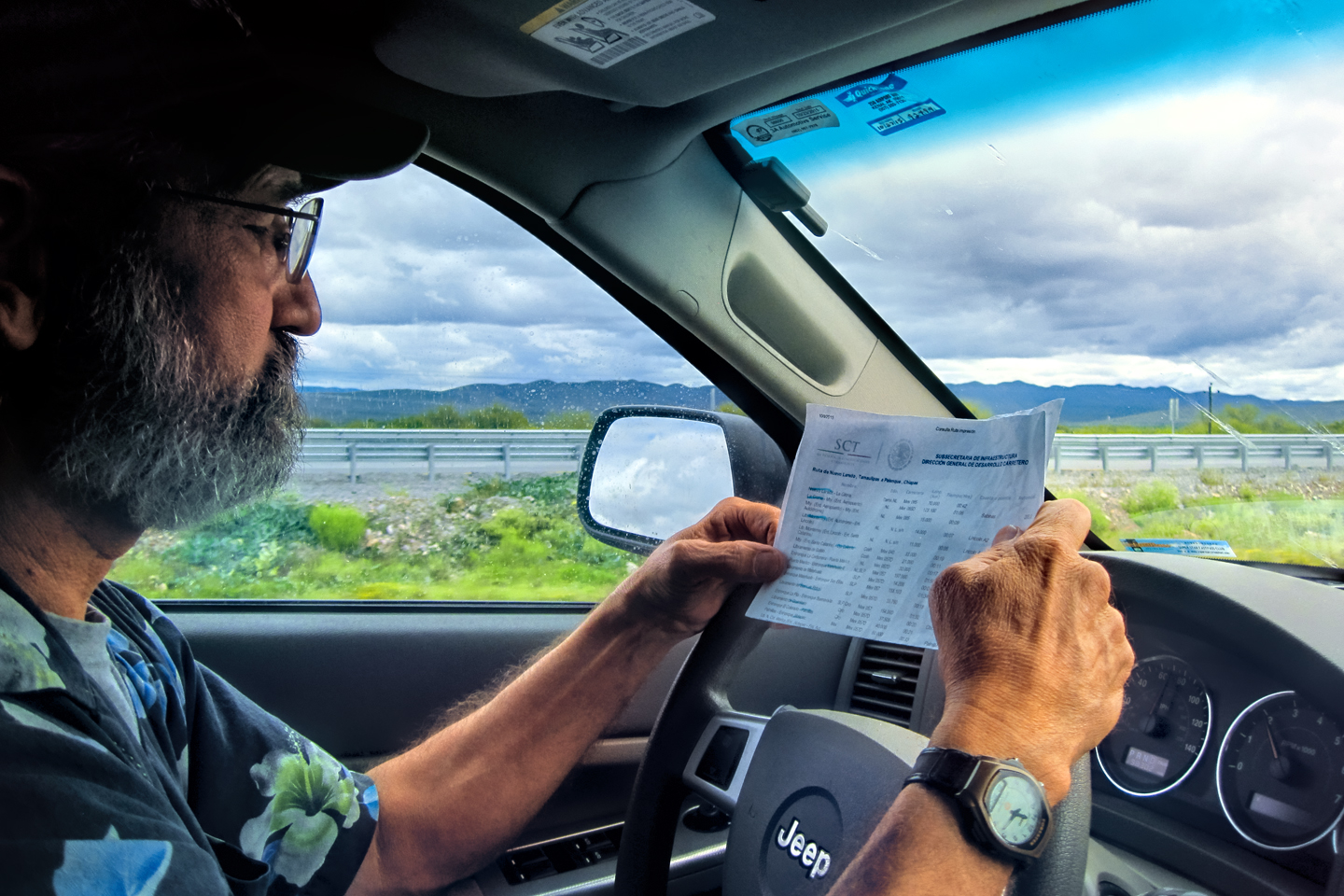

On Day 14, we had one last French Bakery breakfast at our hotel, the Maison Tulum, then we gassed up the Jeep, checked the oil and tires, and hit the road. MX 307 is the principal north-south highway connecting the cities and towns along the Riviera Maya. From Cancun to Tulum the road runs parallel to the coastline. After Tulum, it veers slightly inland before dropping south to Chetumal, on the border with Belize. We planned to head in that direction, but we’d decided against crossing into Belize, so at the junction with MX 186, Just before Chetumal, we would be turning west toward Escárcega, on the other side of the Yucatan peninsula. We planned to visit at least three Mayan sites this day, beginning with a place called Muyil, which neither of us had ever heard of before I noticed it on our map. It was just 15 miles south of Tulum, but it had a reputation for being one of the least crowded attractions in the area.

First we took the turnoff for Chunyaxche, then the turnoff for Muyil. The parking lot was right beside the road; the only vehicle in view belonged to the caretaker.

MUYIL

The name of the Mayan site is Muyil, but the surrounding community is Chunyaxche, and the two names seemed to be interchangeable. For being so close to Tulum, Muyil had an isolated, far-away feel to it, and they certainly weren’t kidding about the lack of crowds. We arrived just past 9 AM, and wandered the grounds for close to an hour. The whole time we were there, we were the only visitors in sight.

Parking was free, and entrance to the ruins was just 50 Pesos apiece (less than $3), making this the cheapest ruin we’d been to so far. Then again, it was also the smallest ruin we’d been to so far. Muyil/ Chunyaxche was named for two adjacent lagoons, connected to each other and to the sea by canals. Big canoes filled with trade goods plied the Caribbean coastline in the Mayan era, and they used the lagoons as a safe harbor. Muyil provided docks, and became a transfer point for goods moving inland. Trade gave them the wealth required to build a serious pyramid, large enough to belie the small size of their community. (Ever larger monumental construction was the ultimate form of one-upsmanship among Mayan Nobles).

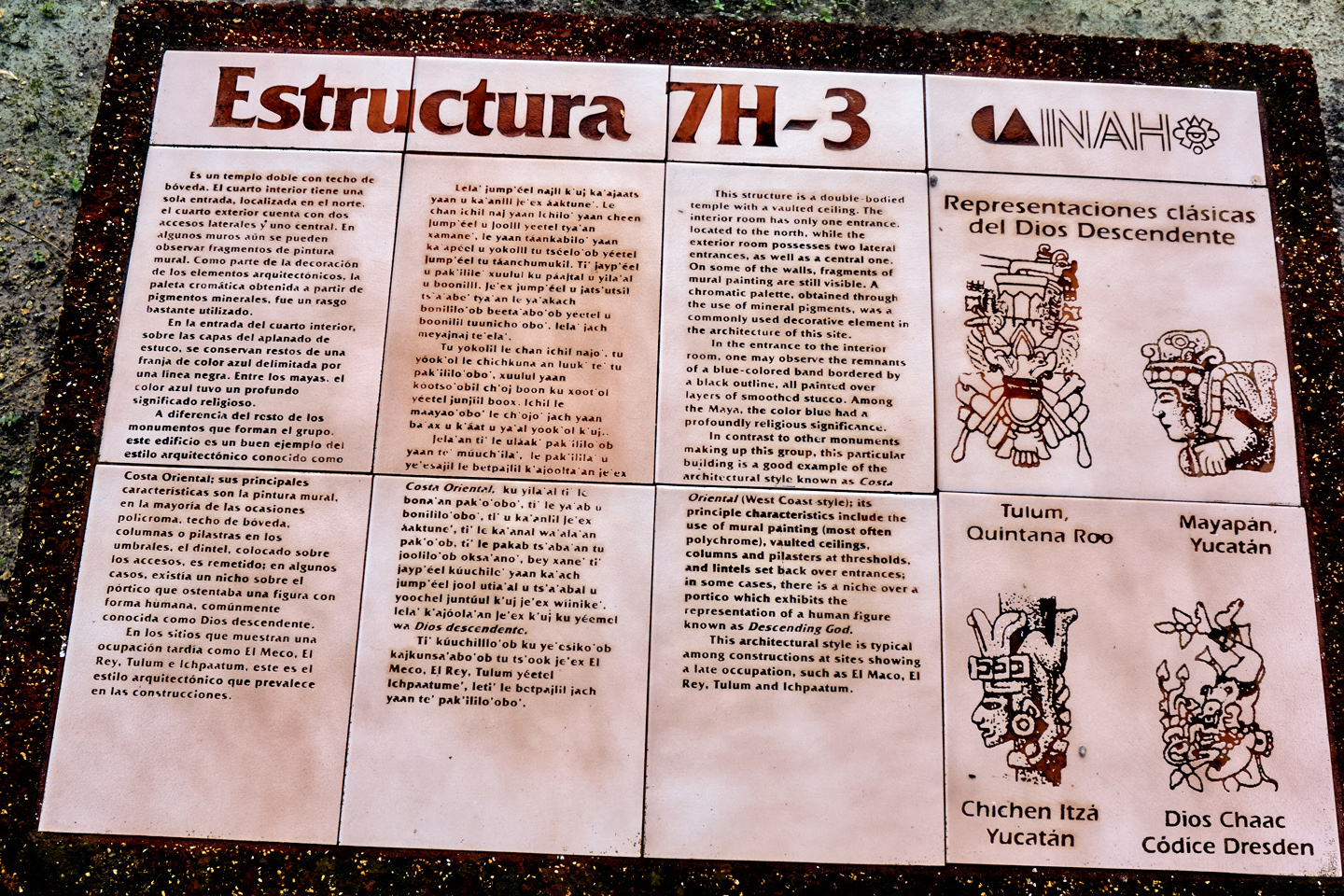

Just beyond the rustic ticket booth, a pathway leads past a site map and other signage to the first of Muyil’s buildings, a temple known as “Estructura 7H-3,” a relatively intact structure reminiscent of the building style we saw at Tulum, with a vaulted concrete ceiling, and faded remnants of painted murals on some interior walls. The temple is backed by several larger structures that are crumbling into rubble.

Muyil’s largest structure is the Castillo, a tiered pyramid built of stacked stones mortared together. When viewed from the back side, it’s much like the Peten style pyramids of Tikal.

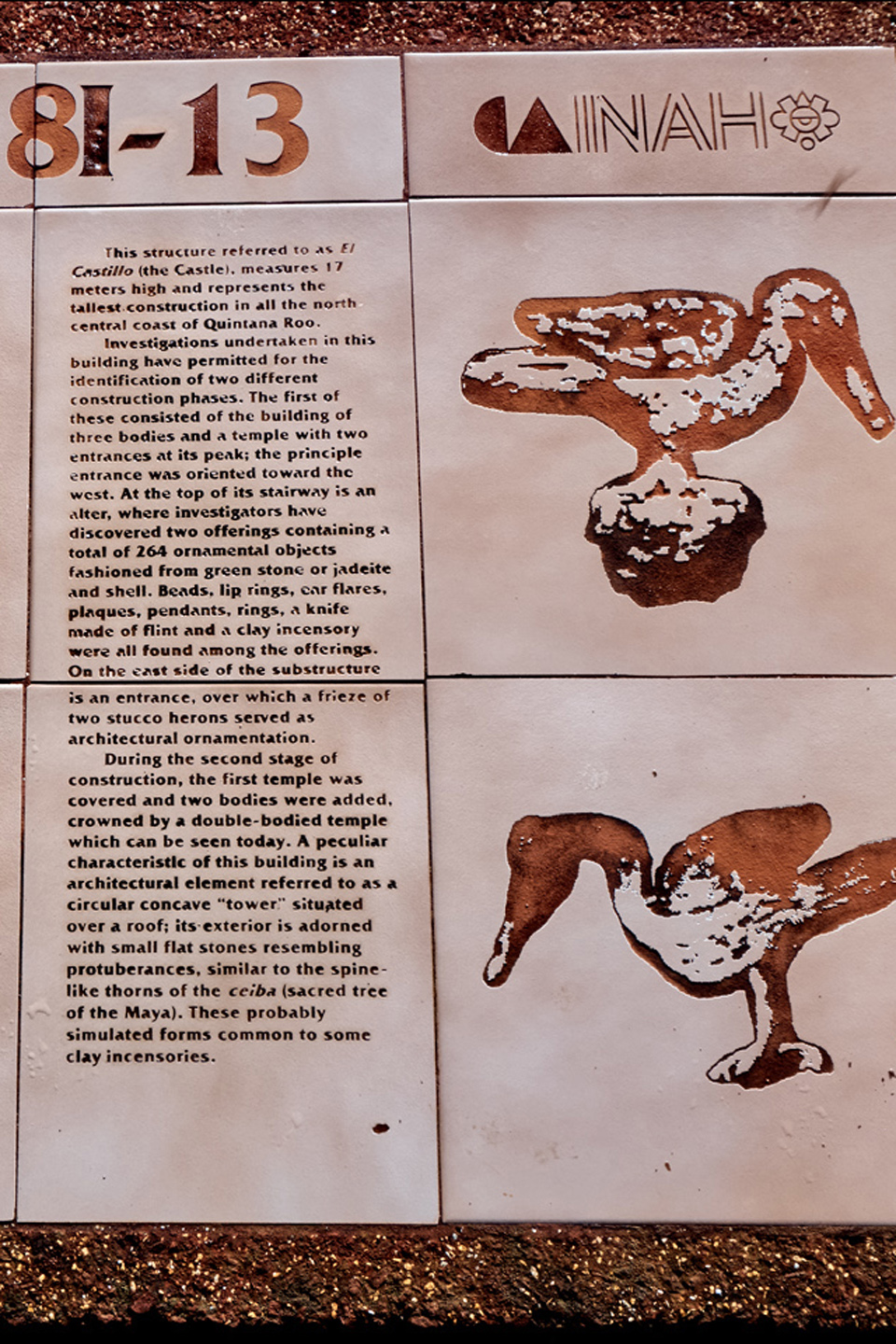

We wound our way through the forest on a well defined path, and after five or ten minutes we approached a large clearing. Rising up above the tree tops was a five-tiered stone pyramid. The painted stucco that once smoothed the exterior is long gone, along with at least half of the carved and fitted facing stones. What’s left, at least on the back side, is clearly exposed as a very large pile of rocks. Near the top there were two stone panels with birds–herons–carved in relief. The caretaker was quite proud of these, as they were newly installed reproductions that he considered “much nicer” than the originals.

Officially, the pyramid is Structure 8-I-13, often referred to as the Castillo, the Castle. It’s not huge, as pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

Continuing along the path was like hiking in deep jungle, but there was an incongruous, almost continuous rumble as the trucks passing on the nearby highway hit a downgrade, and applied their engine brakes. (BRUUMMM-bum-bum-BRR-A-A-A-P-P-P!) Mike was filming with his Go-Pro camera while we walked, and came within an inch of smacking face first into a barely visible silken web strung across the path at eye level. The spider was a golden orb-weaver, known for huge, complicated webs; fortunately for us, this one was a dude. The females of that same species are 80 times larger than the males–think, tarantula size. Nose to nose with one of those? No, thank you very much.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

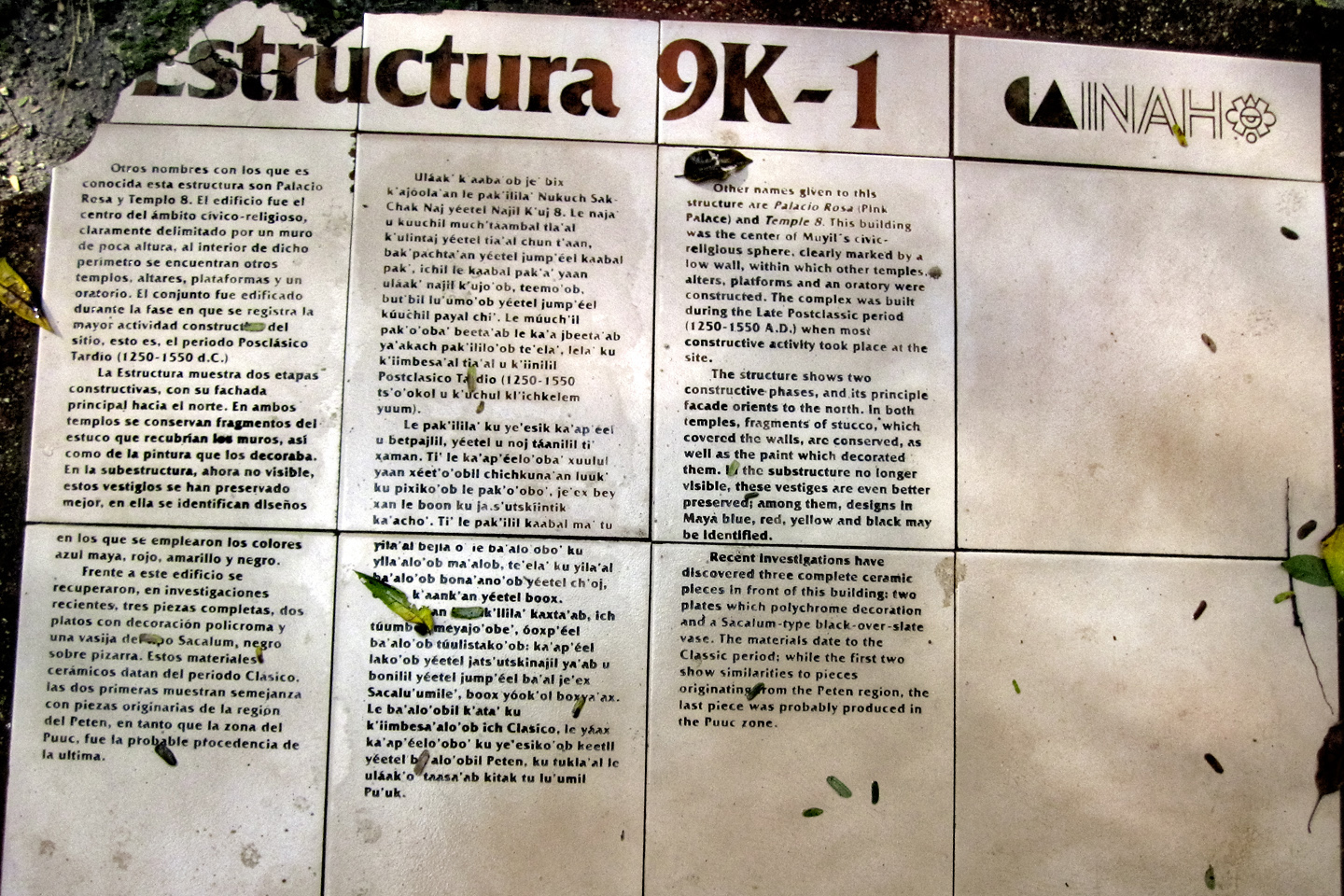

We kept going most of the way along the path, to Structure 9K-1, aka Temple 8, aka the Pink Palace; so called for the reddish tint of the stone

Male golden orb weaver spider. We were glad not to meet his mate: the females are 80 times this size, almost like a tarantula!

Strangler fig (with buttressed roots!)

According to the site map, there was another temple further ahead, at the ultimate end of the path, but right about then, the dark clouds that had been building since we arrived opened up and started POURING on us! Mike was well behind me, still viewing the world through his Go-Pro, so intently that he almost missed me when I came running toward him. “Let’s get out of here,” I shouted as I lumbered past, “Before we get soaked!” I used my raincoat to shield my cameras, leaving everything else exposed, so by the time we got back to the Jeep, I looked like I’d been showering with my clothes on.

It was still early when we left Muyil, heading south on MX 307. We hit a town with the unlikely name of Felipe Carillo Puerto, where we were shunted off onto a poorly marked construction detour that had us driving through neighborhoods, with stop signs at every corner.

Headed south on MX 307

Street scenes in Felipe Carillo Puerto, a small town south of Tulum.

Topes! (Toe-pays): Even when they’re well marked, they’re a pain!

At the junction with MX 186, three hours south of our starting point in Tulum, we kept to the right and turned toward Escárcega, four hours of slow state highway to the west. Our next destination was a Mayan city called Becán, just short of the halfway point on that stretch of road. That’s where we left the State of Quintana Roo, and entered the State of Campeche. In the small town of Xpujil, we went through a roundabout featuring a statue of a Campechana, a woman of Campeche, and a second sculpture, modern, but with Mayan themes, titled “Caracol de la Vida,” the Shell of Life. That one, I must confess, was a little strange!

BECÁN

Aside from the brief rain storm that soaked us at Muyil, this had been a perfect day, weather-wise, with temps in the high 70’s, and beautiful blue skies. We’d been on the road for almost five hours, altogether, making good time, when we finally spotted a sign that read Becán, along with the pyramid symbol that indicates a ruin. I’d circled it on our map the night before, mostly because it was directly in our line of travel. Other than location, I knew very little about the place. We slowed and made the turn, driving past a rustic hotel. A short distance further along there was another sign, and an empty parking lot. Just like at Muyil, we appeared to be the only visitors.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

A path led from the parking area into the trees, and after a short distance, the vegetation closed in on us, almost like being back in the jungle. We walked for a quarter of a mile or so before we finally spotted the entrance booth. Couldn’t miss it–the path actually went right through the building! The site’s caretaker (the only staff person in evidence) charged us 80 Pesos apiece to enter, which was more than Muyil, but less than every other place we’d been.

The caretaker asked us to add our names, along with our home towns, to their guest book, a custom from a bygone era that I found quite charming. I wondered how many books they’d filled with names over the years, and how far back they went?

There was a site map posted outside the entrance booth, and we paused for a moment to study it:

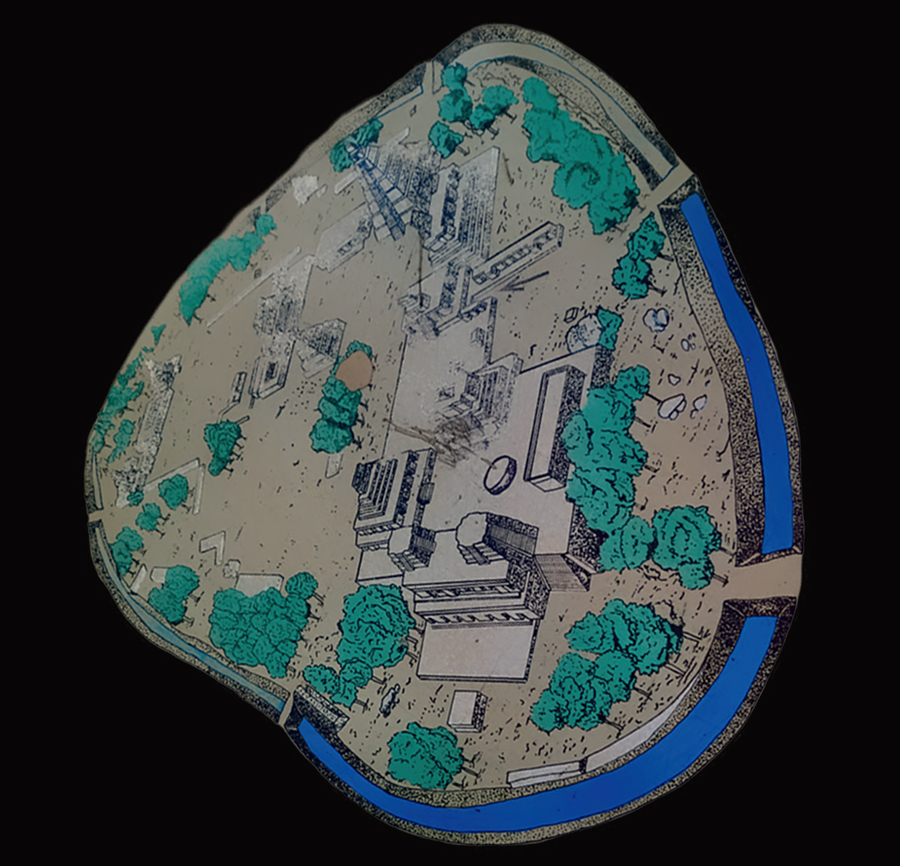

This was the first plan of the city that I’d seen, and the name of the place suddenly made sense: Becán, which translates from the Mayan as “Stream formed by Water.”

In this case, the stream in question was a circular canal that surrounds the old city center. This wasn’t a natural formation. This was a moat, pure and simple, backed by earthworks that created a dual barrier for defensive purposes. All you can see from ground level are scattered, disconnected segments, but when viewed from the air, or better yet, from a satellite, the outline of the original channel is still plainly visible.

There was a time when scholars viewed the ancient Mayan society as a peaceful theocracy, comparable to that of the Tibetan Buddhists. The discovery of this defensive moat at Becán was an important revelation, evidence that the Mayan version of a theocracy might not have been quite so peaceful after all. At Becán, they obviously went to a lot of trouble to protect their city. It’s only fair to wonder why they felt that was necessary.

The Main Plaza at Becán: a grouping of large stone buildings surrounding a circular altar.

According to the map, there were originally seven bridges that crossed the moat. We followed the main causeway to a wide staircase inside the walls; that led us up to the main plaza, where several massive stone buildings surrounded a circular altar. Stones on the altar, and on several other structures in the old city center still bear traces of the red pigment that once colored many of these buildings.

We climbed the steep steps on the front side of the building identified as “Structure I.” Once we were safely up on the first level, we made our way around to the back side, where we gained a completely different perspective. A wide terrace ran the entire width of the building, and from there, we had a bird’s eye view of the multi-level terraces down below us. Trying to imagine this area filled with people, with the pomp and grandeur of the Mayan priests and Nobles in their flowing robes and elaborate feathered headgear, and these buildings all intact, stuccoed, and painted in bright colors. It would have truly been something to see!

The back side of the temple known as Structure 1 was partitioned into rooms, possibly living quarters for the city’s elite. The view, looking down, was amazing!

CLIMBING DOWN AN UP PYRAMID

CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND

There’s a trick to climbing a Mayan pyramid. Many of ’em are proportioned opposite to a standard staircase, with narrow treads and tall risers; (in this set of photos, each step is a full foot in height). The pitch of the steps is so steep, you can’t approach them straight on. For safety’s sake, it’s best to keep your feet sideways on the steps, with your body parallel to the stairs, so you can move diagonally as you climb. Your feet get a better purchase, and you’re less likely to slip. (Slipping on a Mayan staircase could be a disaster!) Mike demonstrates his technique, on steps so steep, it’s more ladder than stairs.

Several of the structures around this main plaza were partitioned into individual rooms, many with concrete benches, thought to have been used for sleeping. These had to have been elite accommodations for important people, the royal family, the nobility, the high priests. I’d have to hope, for their sake, that these spartan quarters were fixed up a bit when they were in use. Blankets, maybe some curtains, and a nice soft mattress? Stripped down to cold bare stone, these digs were about as inviting as a prison cell–albeit without the iron bars.

There was a second, smaller plaza to the west of the main plaza, still inside the city walls. We started to walk over that way, but I called a halt to talk it over with Mike. We still had a two hour drive to Escárcega, where we planned to stay the night, plus, there was one more stop I wanted to make. Considering the time, I figured it was best if we cut it short at Becán. Mike agreed, so we turned around, and headed back to the parking lot.

The west plaza’s buildings were concealed from view by the trees, so we didn’t even realize that Becán’s largest pyramid was over there, just out of sight. Like a couple of dummies, we missed what might have been the best part of the ruin, all for the sake of saving a few minutes? There’s a lesson here: if you should ever decide to forego seeing something, especially after you’ve traveled a long distance? You’d best know exactly what you’re skipping, before you walk away!

Intricate Chenes Style stonework

Like all the Mayan sites we visited, there were fascinating details everwhere, when you looked more closely. Inside one of the stone rooms there was a wasp’s nest unlike anything I’d ever seen, the size of a volleyball with intricate patterns, a perfectly symmetrical work of art. When I looked at the ground, I spied a column of leafcutter ants, each of them hauling a sliced bit of leaf four times the size of their bodies, cogs in the endlessly moving machine that keeps their colony fed. And then there’s the stone in the ancient buildings, the skillfully carved segments that fit together like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Unusual wasp nest; Leaf Cutter Ants

Every Mayan city we’d seen so far was different from every other. There were common elements, but there were also major regional distinctions, and much of what we were seeing at Becán was unlike anything we’d encountered elsewhere. This part of the Mayan world was known as the Rio Bec region, and the school of design that predominated here was known as Rio Bec Architecture. I did a bit of study on all this, after the fact, and what I found is utterly fascinating:

RIO BEC ARCHITECTURE

“Rio Bec” was a style of architectural design that was largely based on illusion. Instead of traditional step pyramids topped by temples, the Rio Bec Maya built wide structures with twin towers on either end. The towers narrowed toward the top, so if you looked up at them from below, they appeared to be much taller. False doorways lead into alcoves with no exits, and buildings that appear to be temples are actually solid structures with no interior space.

Stairs were mere decoration: these steps for example, lead to a blank wall. In the Rio Bec region, form won out over function, and many of the massive structures they built here were–no joke–strictly for show.

It was almost 4:00 PM when we left Becán, and we needed to be in Escárcega, 90 miles west, before the sun went down. Even at that, I figured we had just enough time to make a VERY quick stop at Becán’s sister city, a small site called Chicanná, less than three clicks up the road. The main reason I wanted to stop there was the name: Chicanná, a Mayan word that translated as “House of the Serpent Mouth.” The name supposedly described a particular building among the ruins, and that was something I just had to see.

CHICANNÁ

We left Becán, and we were barely underway when we spotted the sign with the pyramid, pointing to the left:

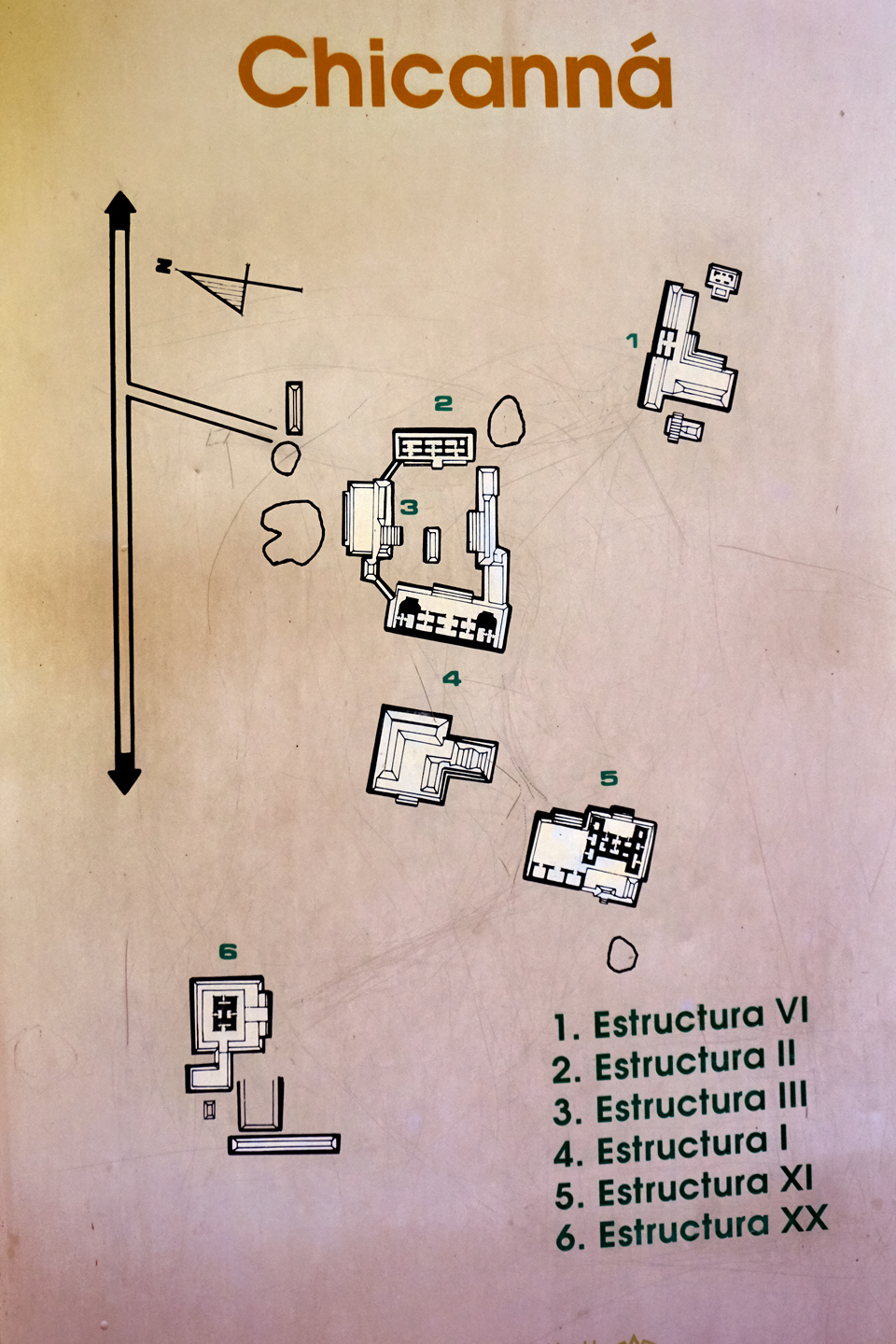

Do I even need to say it? Ours was the only vehicle in the small parking lot. We stopped at the ticket booth to pay the 50 Peso entry fee, then studied the site map:

There were just six buildings, most of them in one cluster. We had 30 minutes to see the place, so we got straight to it!

I did some research, (after-the-fact), and the information I turned up was really very interesting. Chicanná was first occupied around 300 BC, about 50 years after Becán got its start, and was abandoned around 1100 AD, which was about 100 years sooner than Becán . It’s thought that Chicanná was actually an exclusive enclave for Becán’s elite, a segregated suburb for the rich and famous. The houses were finer, the temples more ornate. Nothing was too elaborate for the noble folk, and when times were good, they lived like kings. Chicanná peaked early, from the time of its founding until around 250 AD, and it remained, throughout its existence, intertwined with its patron, Becán. There’s nothing big here, no pyramids, just an assortment of smaller structures, done in a hodge-podge of architectural styles.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

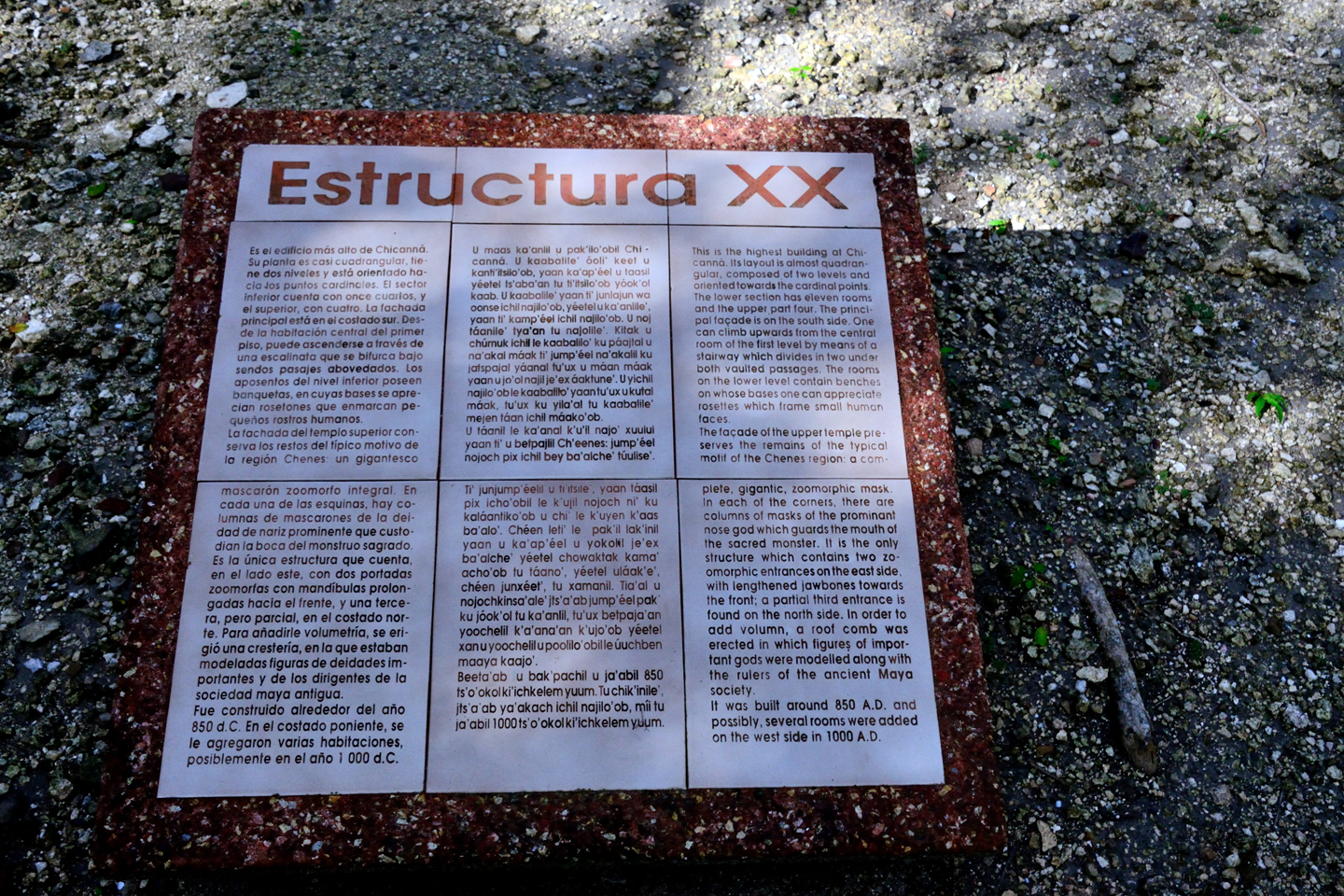

We turned right when we first entered the ruin, following a path which took us to “Structure XX,” the remains of a temple that, despite the ravages of time, is still the tallest building in Chicanná. The structure is a perfect example of mongrel architecture. The temple at the top is pure Rio Bec: a doorway leading to a blank wall in a solid structure with no interior space. Viewed from the front side, the entire building becomes a giant zoomorphic mask with an open mouth, a feature of the Chenes style of Mayan architecture, and the carved stone facades, especially the multiple depictions of Chac, the rain god, were influenced by the architectural stylings of the Puuc region.

Chicanná was a city in the jungle, and that’s what it felt like, walking around the place. The site seemed to be mostly uncleared, and essentially unrestored, lacking the manicured, park-like look of the more famous Mayan cities. I’m sure there was an enormous amount of effort put into exposing the principle structures here, but these tropical trees grow so quickly, they’re already starting to take over again. Being the only visitors, it was very easy to imagine what it would have been like here in the early days, before there was any such thing as tourists in the Yucatan.

Conical towers at either end of a stone platform, designed to give the illusion of larger size.

The buildings in Chicanná show the influence of half a dozen distinct schools of Mayan Architecture, but at the core, the underlying theme is that illusive style known as Rio Bec. Structures are built atop a platform, and at each end of the platform there is a tower that comes to a point at the top. When stuccoed, finished, and painted, these towers would appear to be taller than they really are to an observer looking up at them from their base.

THE HOUSE OF THE SERPENT MOUTH

We were already running short of time, but we’d saved the best for last. A rectangular building with two doorways, one of which was surrounded by Puuc style bric-a-brac. A complex geometric pattern which, if you looked closely, had eyes and a snout! The doorway was a mouth, surrounded by stone teeth. A little bit of imagination is required to see it, but the Chenes-style construction of this facade turned the entire building into the head and mouth of a serpent!

The facade would have been painted, back in the day. If you look closely, you can still see traces of red pigment in the recesses between the stones. The inside of the serpent’s mouth would have been red, the color of blood; the teeth white, and the eyes yellow, along with shades of green, blue, and black, to complete the pattern. The Maya were a people who loved color, and with a temple like this one, they would have gone all out. The “House of the Serpent’s Mouth” was a place where important ceremonies took place, grand spectacles that we can only imagine. When the Mayan priests in their colorful feathered robes disappeared through that doorway, they were stepping through the mouth of the Great Serpent into the abode of the gods, and when they emerged again, they were imbued with god-like power.

I would have loved to spend more time at Chicanná, but it was already 4:30, and we were going to have to really push it to make Escárcega before sundown. We jumped back onto MX 186, and I drove as fast as I dared, with Mike providing a second set of eyes to help us avoid the hazards in the road–especially the topes! Most of them were well marked and painted yellow, but in some cases there were so many skid marks on the yellow that the hump had turned black, and blended with the asphalt, practically invisible. We hit one of those at highway speed, and literally went airborn! Needless to say, we wasted no time on that stretch, and rolled into Escárcega at 6:30, just as the sun dropped below the horizon.

We hadn’t made any reservations, so we kept our eyes peeled for hotels, and spotted a place called the Global Express; they had a room for us for 900 Pesos (a bit more than $50). That seemed high, but we were too tired from the drive to shop around for something cheaper. We’d been pretty spoiled by some of the nice places we’d been staying, so this hotel was a disappointment. Not because it was bad; more because it was boring! We weren’t planning to hang around Escárcega, so all we really needed was a clean bed for the night, and the Global Express served that purpose well enough.

This really had been a long one. More driving than anything else, but with three more Mayan cities checked off our list, it felt like we’d had a very full day. I had images of temples and pyramids jumbled together in my brain. I’d taken hundreds of photographs, counting all my shots from Cobá, so I was going to have my work cut out for me, just keeping all those images organized. I was honestly too tired to fool with any of that, there in Escárcega. We had a quick dinner at a nearby restaurant, then went back to the hotel and crashed, planning an early start for the next day.

Next up: Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha!

The collage below features additional photos taken on the road in Mexico by my inestimable shotgun rider, Michael Fritz. (Michael is responsible for many of the photos in this series of posts). Click any image to expand them to full screen:

(Unless otherwise noted, all other images are my (or Michael’s) original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen

Michael Fritz, “Elmo,” 1949-2025

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

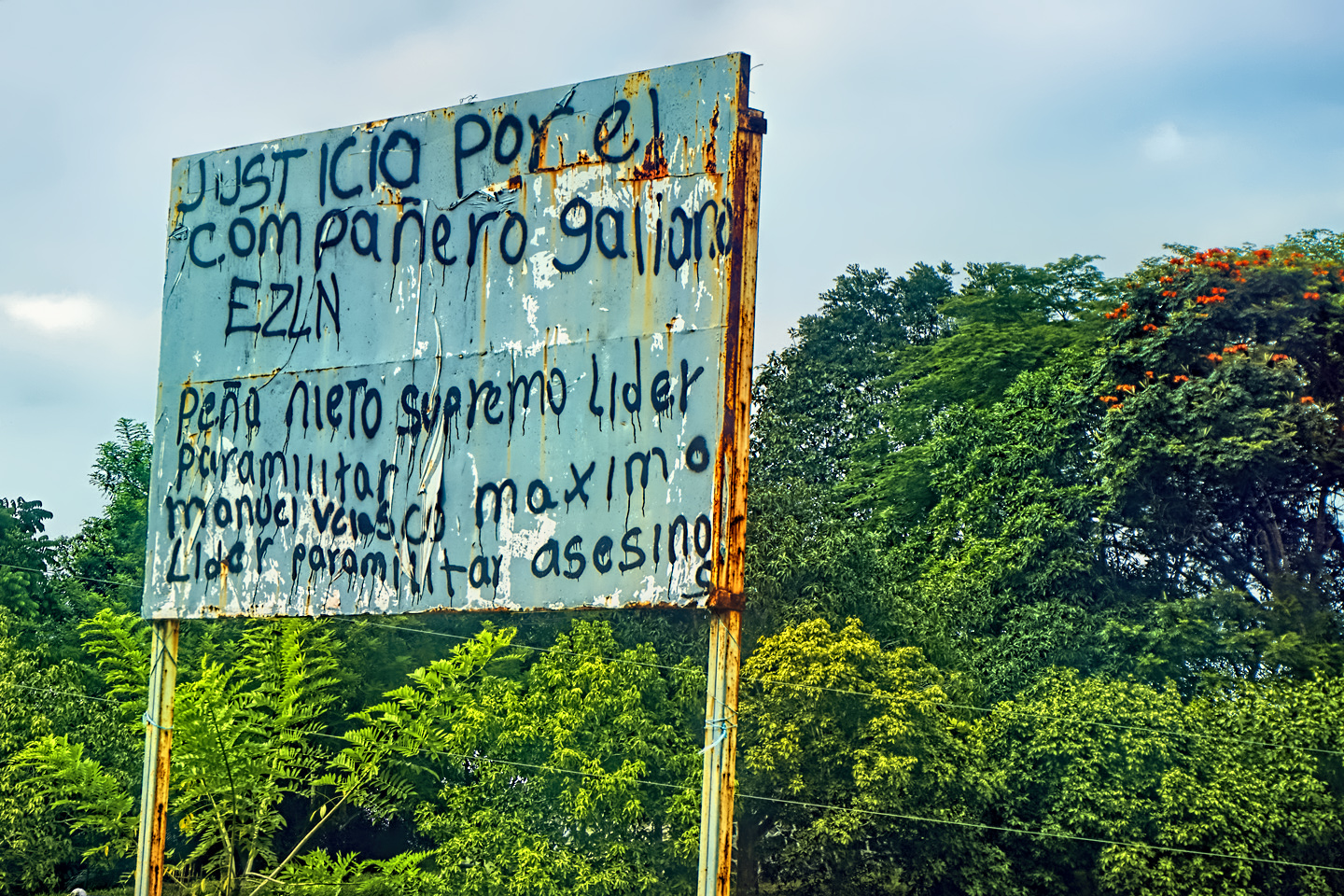

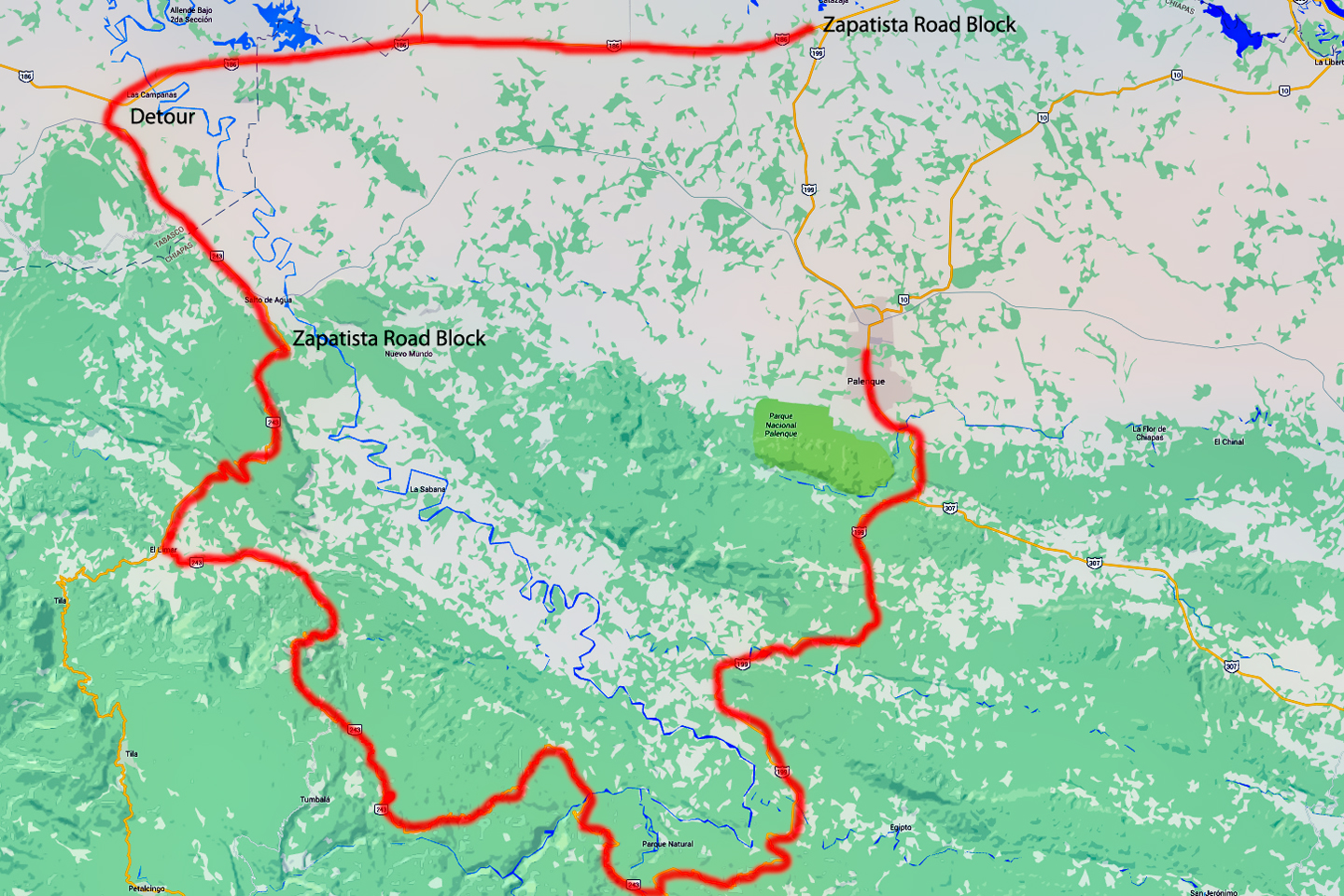

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn't huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

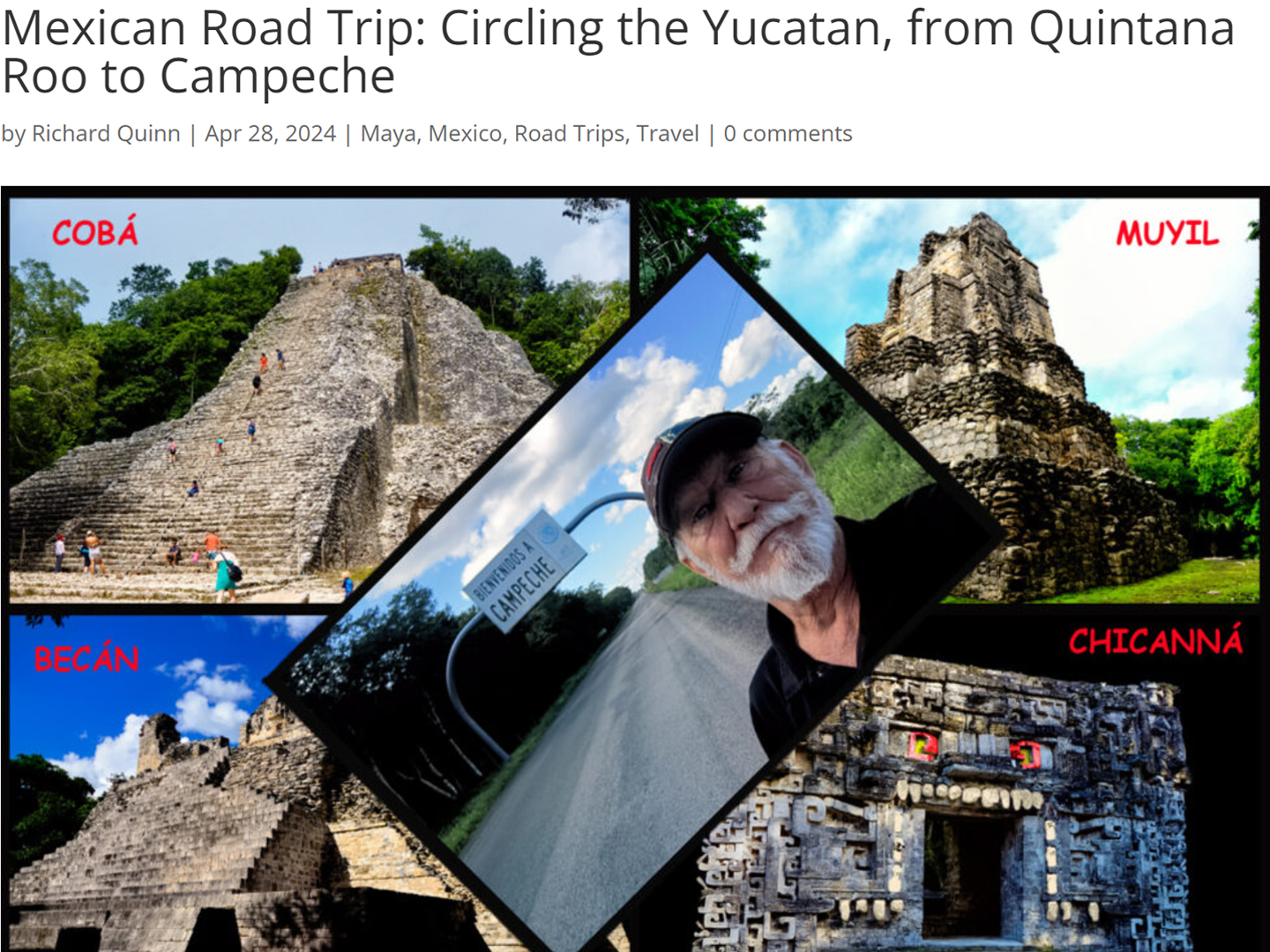

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

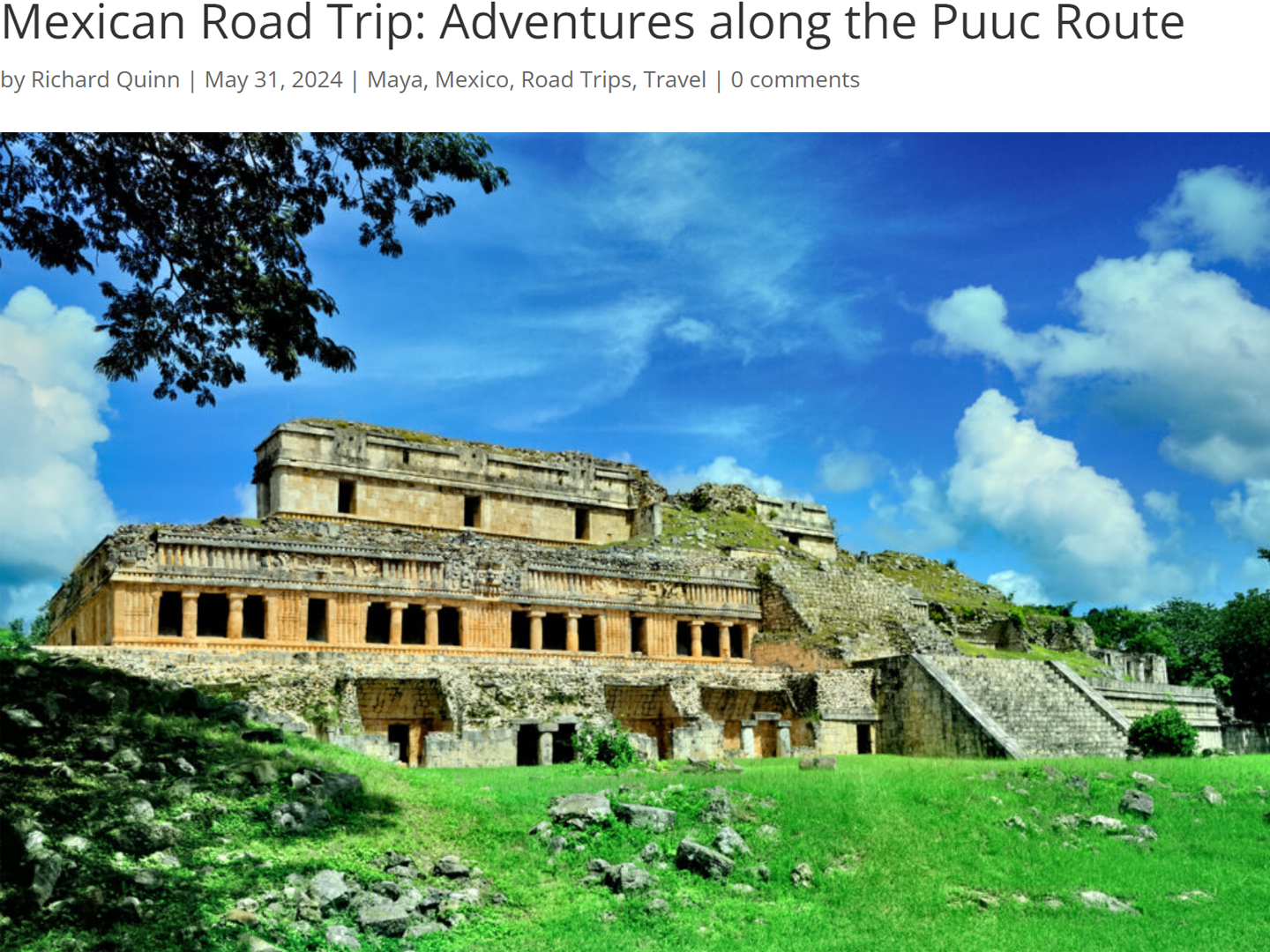

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we're left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it's 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

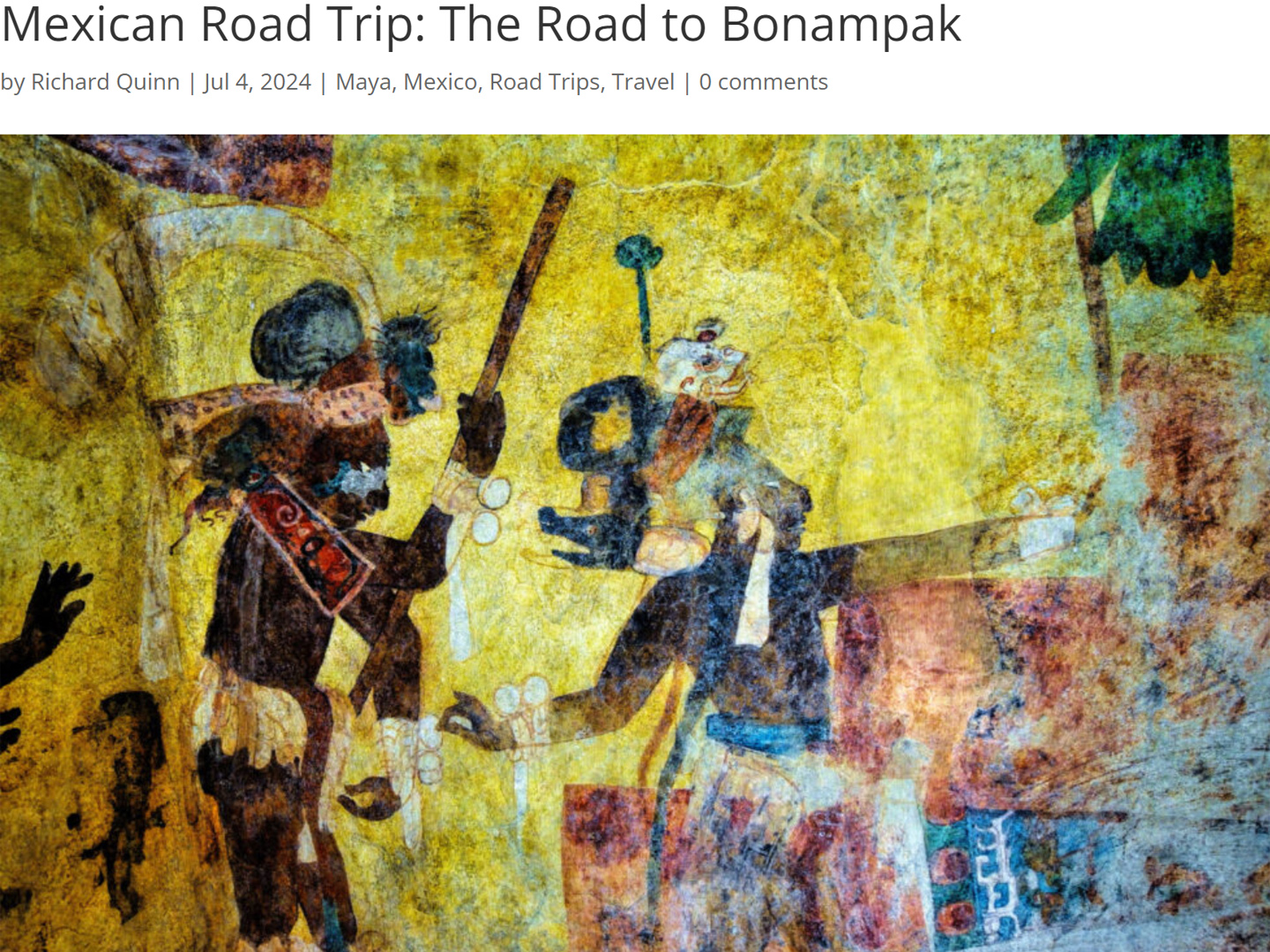

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

As we drove away from the toll plaza, a State Police car that had been parked off to one side made a fast U-Turn and started following me. A moment later, he turned on his flashers and gave me a short blast on his siren, motioning for me to pull over. Two uniformed policemen got out, and approached me on the driver's side. One of them hung back, apparently checking out my license plate before making a phone call.

"Documentos," said the officer by my window. "Licensia, los permisos, seguros, todo eso."

I wasn't sure if I was being stopped for some infraction, or if these guys were just fishing...

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in May, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in May, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer's Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

This series of posts is dedicated to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Michael passed away in February of 2025, after 75 years of a life well-lived. He was unique, and he'll be missed.

Michael Fritz ("Elmo") 1949-2025

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments