DAY 16: Here a Puuc, there a Puuc, everywhere you look, a Puuc!

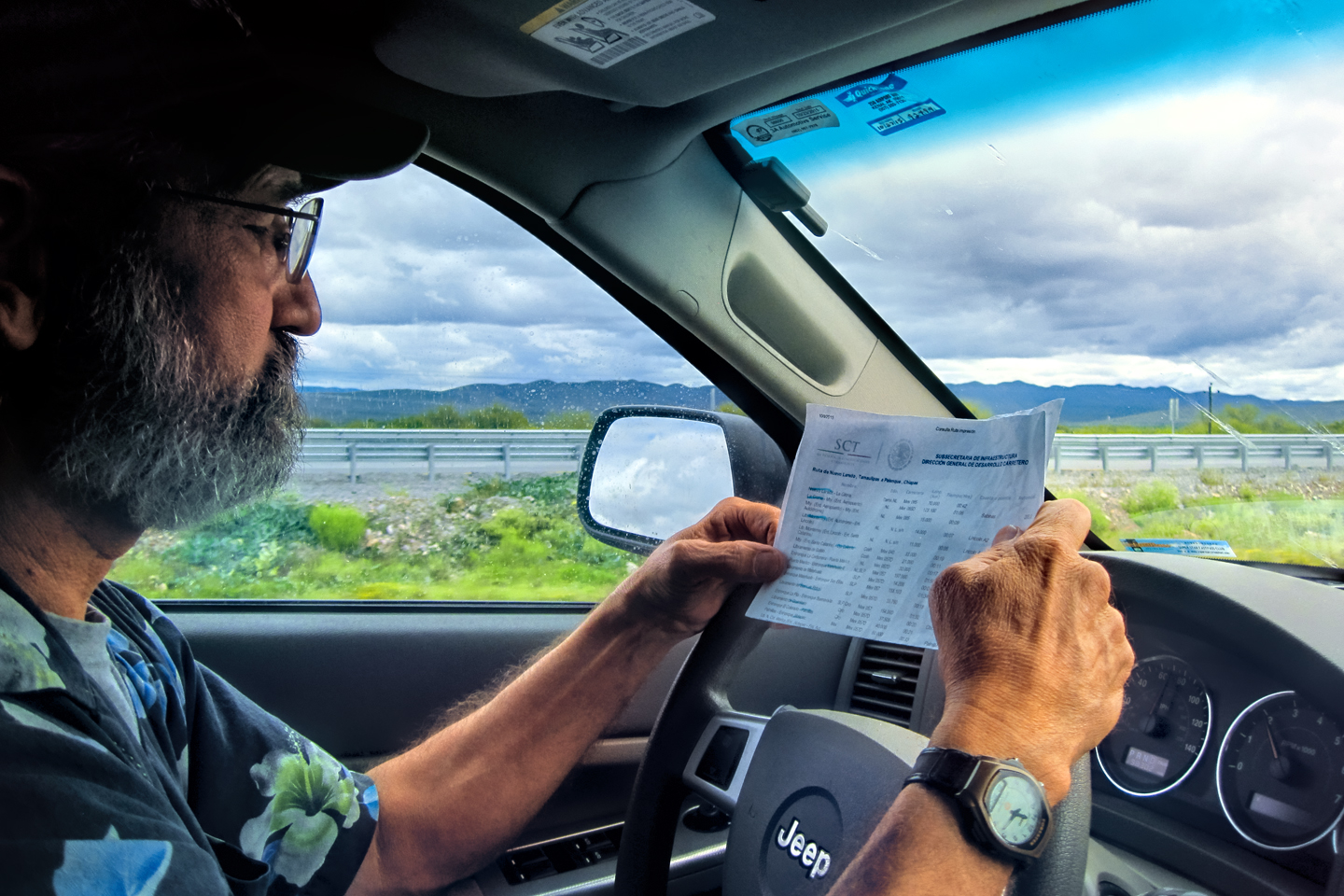

On the 16th day of our road trip, we had breakfast at our hotel, the Hotel del Paseo near the historic center of old Campeche; then we gassed up the Jeep and hit the road. We had a lot of miles to cover, and we were eager to get going!

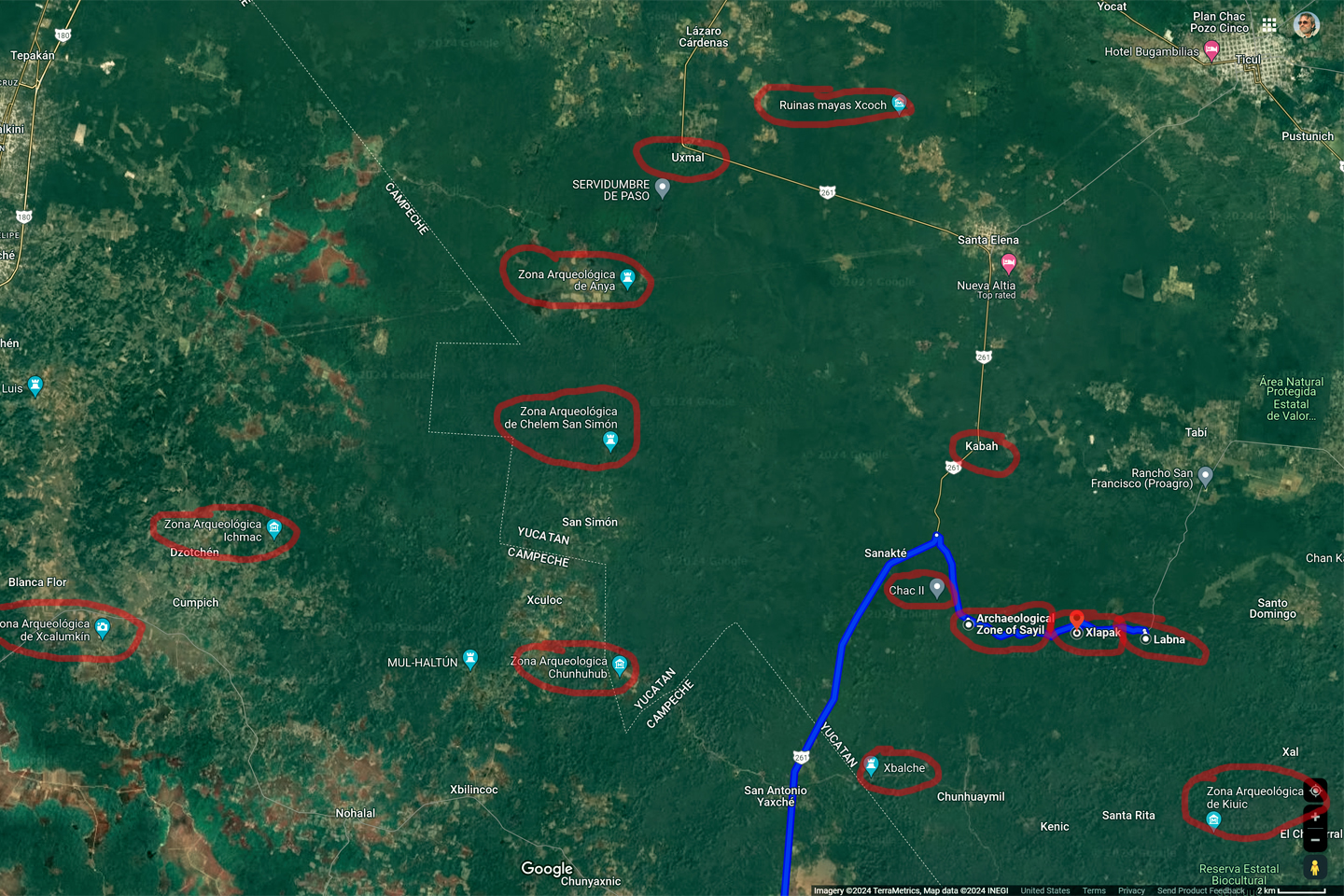

Our goal for the day involved driving a loop through an area known as the Puuc Hills, the only part of the Yucatan Peninsula that isn’t relentlessly flat. In the Mayan era, the Puuc was considered prime real estate, and it contains what is easily the densest concentration of Mayan ruins in all of Central America. The most famous of these is the fabled city of Uxmal, which we’d seen the previous week, but there were dozens of others, and considering how close together they were, this was a unique opportunity to visit as many as four or five small sites in a single day, sort of like a grand finale to our Cook’s tour of Mayan cities in the Yucatan.

The Puuc Hills, with some of the many Mayan sites circled in red.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

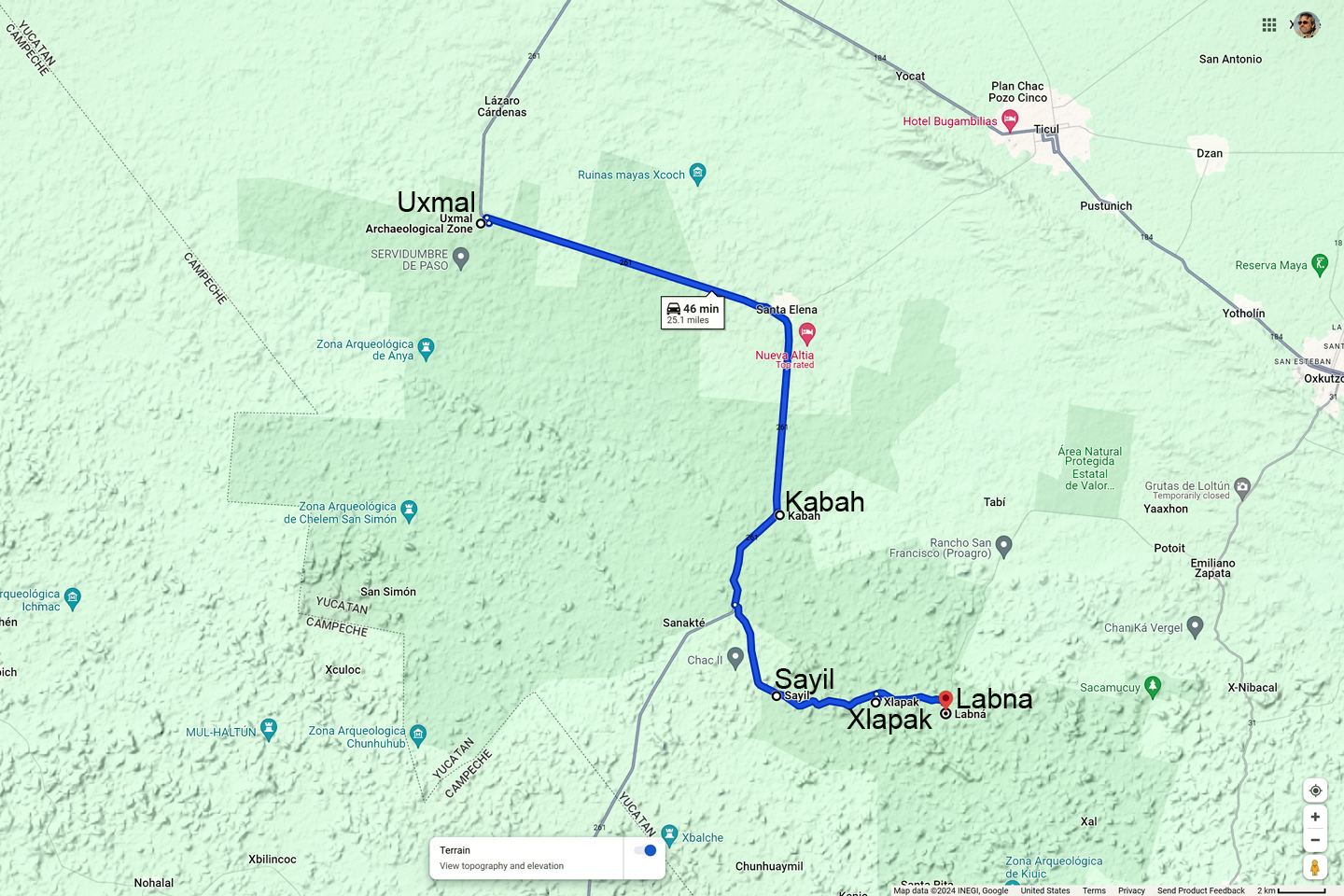

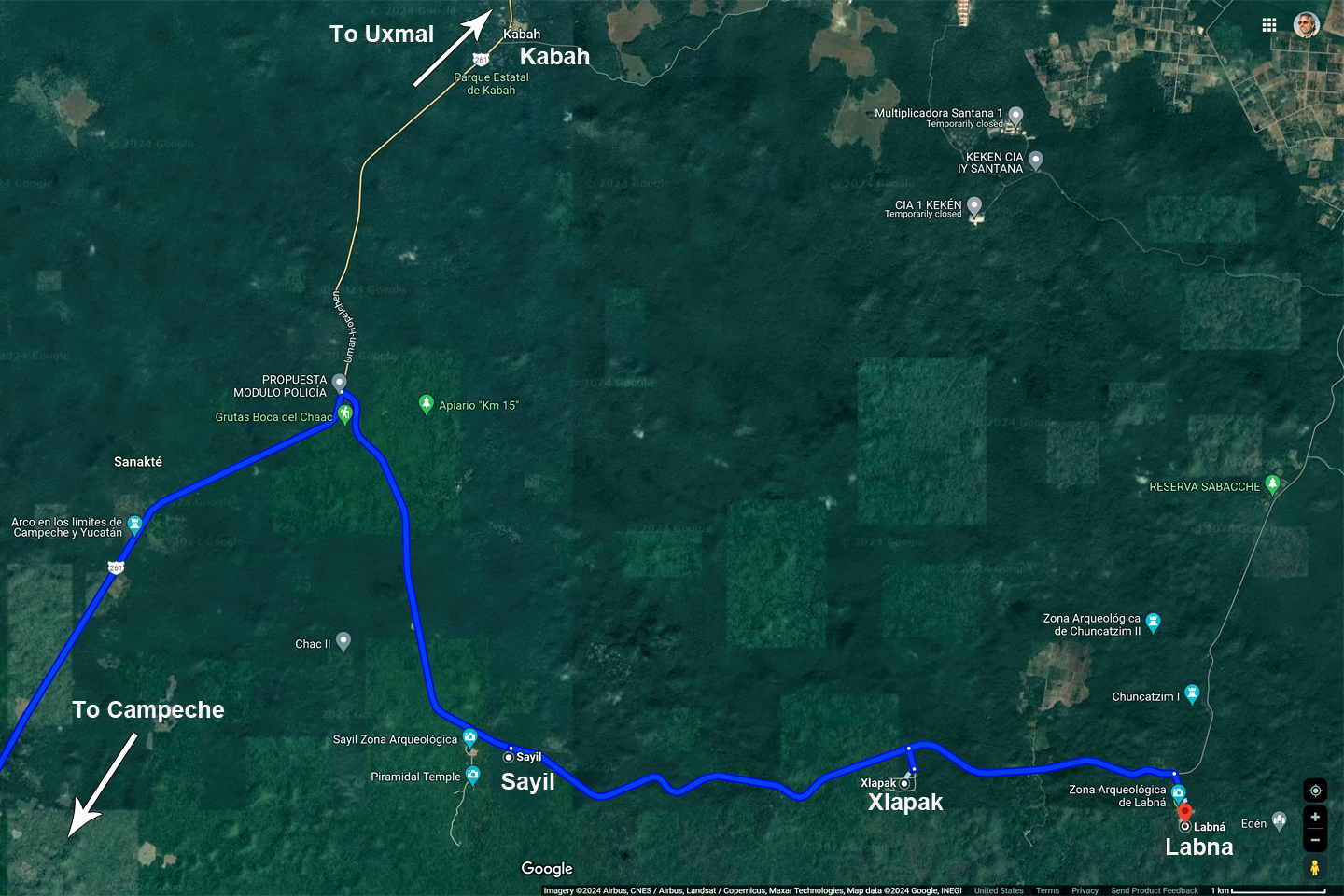

The official “Ruta Puuc,” and the route Mike and I took

THE RUTA PUUC

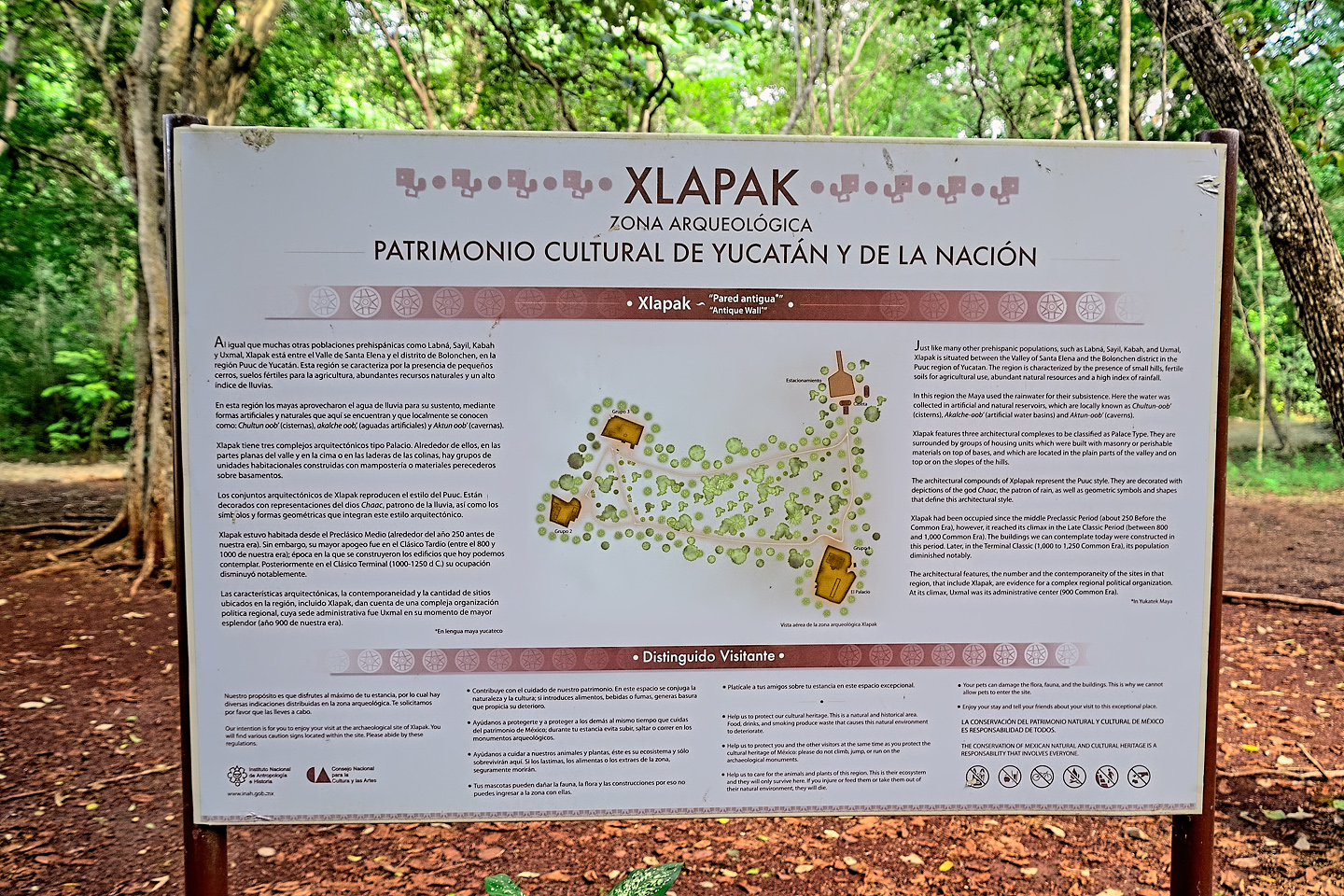

My guide book described an itinerary called the Ruta Puuc (the Puuc Route), a 25 mile stretch of MX 261 that begins in Uxmal, and travels south through low, forested hills, stopping at (in addition to Uxmal) the Mayan cities of Kabah, Sayil, Xlapak, and Labna. It was here among the Puuc hills that Mayan art and architecture achieved its ultimate expression, which is why the Ruta Puuc is included with Uxmal in its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

MX 261 extends all the way to Merida in the north, and to Campeche in the south, running smack through the middle of the Puuc region. Since we were starting from Campeche, and since we’d already been to Uxmal, our plan was to follow MX 261 north until we reached the area where the other four sites were located (all within 11 miles of one another). After touring the ruins, we’d simply turn around and head back to Campeche.

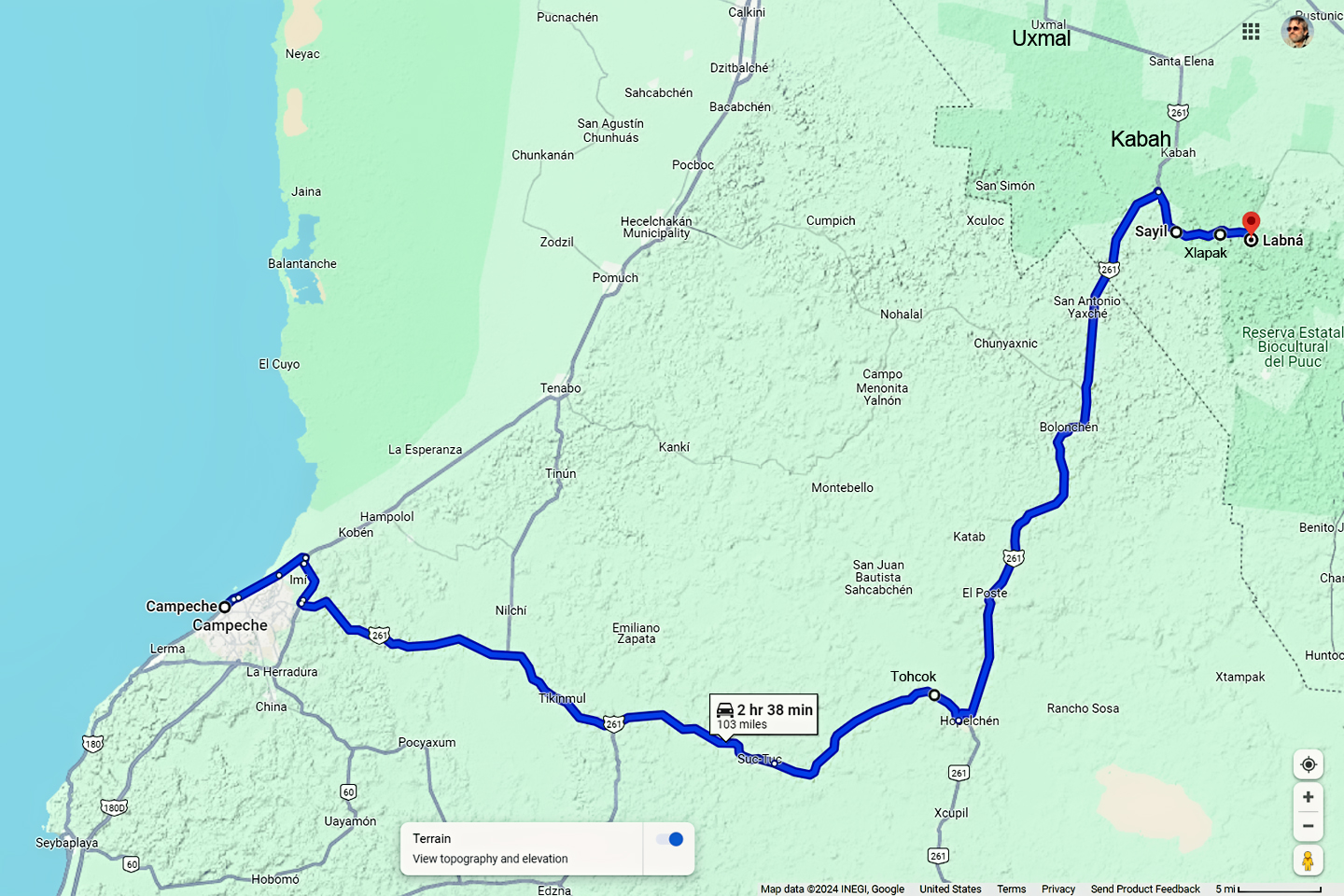

MX 261

Mexico has a national system of modern, well maintained toll roads that make short work of the miles between major cities. MX 261, running east from Campeche, was most definitely NOT one of those! The hazards ranged from deep, dangerous potholes to animals in the road, to strolling pedestrians and children at play, oblivious to the traffic whizzing past. Every hundred meters or so we ran over another Tope, the speed bumps installed to curb velocity through towns and other populated areas. We had to stay ultra-alert to avoid hitting one of them at highway speed, and blowing a tire (or worse).

Just as we reached our halfway point, I spotted what looked like a ruin, right alongside the road. There was nothing in my guide book about a Mayan site in this location, so we were quite curious to check it out.

Scenes along the road, MX 261, East of Campeche

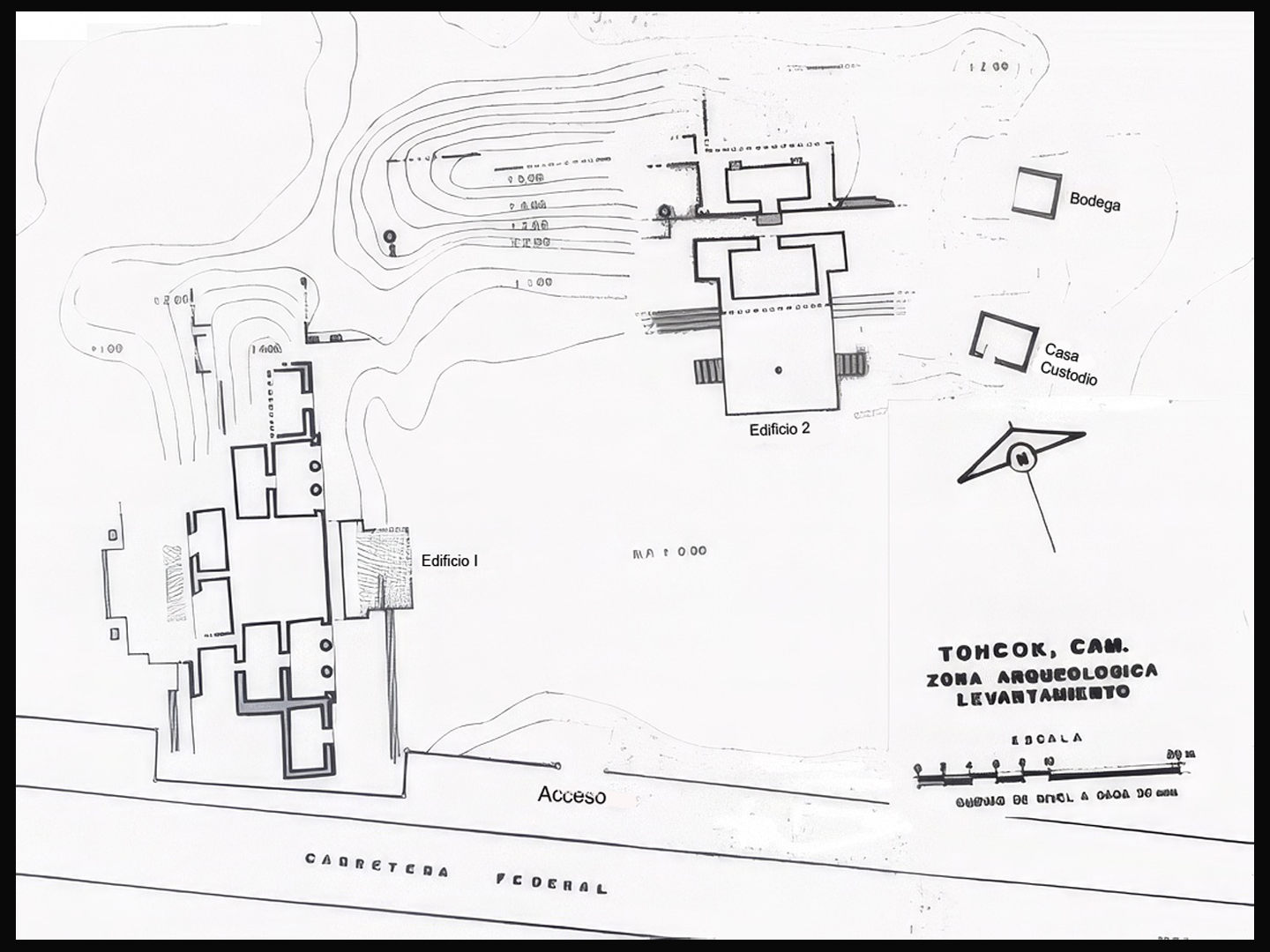

Satellite view of Tohcok, identified as Tacob on road signs

TOHCOK

The first thing we saw was a road sign identifying the site as “Tacob.” I used my phone to do a search on that name, and Google hacked up a page full of links to Mexican restaurants, starting with “Taco Bell.” I scrolled down pretty far, but saw no reference to Mayan ruins. I tried Google Maps, pinched up to the maximum magnification, and found what appeared to be the right spot, labeled not as “Tacob,” but as “Tohcok”? We parked the Jeep on the north side of the highway, then walked across the road to the site. The ruins were surrounded by a rustic fence, but there was a sign beside the gate that said “Open,” in English, no less, so we strolled on through.

We were met by the caretaker, who welcomed us enthusiastically, introducing himself as Pepe. I asked him about the name of the ruin, and he proceded to tell me, with obvious pride, that the place had at least five names, including “Taco.”

“Taco?” I repeated. “Like the food?”

“Oh, yes,” said Pepe, smiling broadly. “But we never use that name.” He went on to explain that “Tohcok” is the name favored by the archaeologists and the map makers, and it translates from the Mayan as the “Place of the Flint Knife.”

“So, the sign on the road is a mistake?”

“Yes, the sign is wrong,” Pepe admitted with a shrug. “But what’s important is that you stopped! We don’t get that many visitors, so, para ustedes, the sign did its job.”

Pepe launched into a well practiced spiel about the history of the site, which was founded around 300 AD, and reached its zenith, along with the rest of the region, during the Late Classic era, around 900 AD. Pepe talked at great length about the Mayan religion, and the human sacrifices that took place on the raised platform in the middle of Tohcok’s plaza. Just like the warriors killed in battle, the sacrificial victims didn’t die in the usual sense; they moved on to a higher plane of existence. He showed me a carving of a corn flower, with the head of a warrior embedded sideways, awaiting his rebirth into the next level of the Mayan cosmos.

The head of a warrior killed in battle, sideways in a corn flower

Several views of the primary structures in Tohcok, a small site surrounded by cow pastures.

Tohcok was first reported by archaeologists in the 1930’s, but it wasn’t excavated until much more recently, and it’s only been open to the public for the last few years. The buildings were constructed in the Puuc architectural style: thin, square cut stone slabs embedded in a concrete core, forming a smooth veneer. There are also elements of the Chenes style, characterized by carved stone motifs on lower walls.

The best thing about Tohcock was the on-site caretaker, Pepe. He was knowlegeable, and personable. It was like having our own private tour guide.

As you walk in, there’s a structure known as the Palace on your left. It’s a two story building, with a central staircase leading to the ruined second floor; there are pillars on the ground floor, and a Mayan arch. Straight ahead from the entrance is a second building, the Acropolis. A ceremonial platform extends into the plaza from that building’s foundation. The base of the platform features elaborate Chenes style carvings of corn plants, and, at the corners, there are nicely carved representations of Chac, the big-nosed rain god. They’ve documented as many as forty more structures associated with Tohcock that remain unexcavated, appearing as little more than overgrown mounds in the cow pastures on either side of the highway,

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

Like most of the Mayan cities in the Puuc region, Tohcok was subordinate to the lords of Uxmal, and in later years, to the League of Mayapan. What that meant, in practical terms, was an obligation to supply materials and labor for monumental construction, and to provide a quota of young men to serve as warriors in ongoing military campaigns. In exchange, they got the support and protection of those larger kingdoms. From the 30,000 foot level, the arrangement wasn’t all that different from the way things work today.

We thanked Pepe for the tour, and slipped him a few hundred Pesos as a propina (a tip). In Mexico, tipping is expected pretty much any time someone provides you with a service, and rightly so, considering the extremely low wages. Even at that, I can’t think of any other situation on our entire trip where the gratuity was more well deserved.

We drove another hour north on MX 261, passing through several small towns, including the village of Bolonchen. This was rural Campeche at its most remote, and I, for one, was loving it!

We had a decision to make at this point. Three of the four sites on our list were immediately adjacent to one another, while the fourth, Kabah, was a bit further away, off by itelf on the road that went north toward Uxmal. Kabah was the one I most wanted to see, but it was also the biggest, and I was afraid that if we went there first, we’d linger too long and run out of time.

It was a two hour drive back to Campeche, and we definitely didn’t want to be on that road after dark. That meant we’d have to head back no later than 4:30, and it was already almost 1:00. It made sense to knock off the other three first, going for quantity over quality, moving as quickly as possible. Afterwards, we’d know exactly how much time we’d have left for Kabah. With that plan in mind, I turned right at the road junction, and headed for Sayil.

Mayan cities of the Puuc Route

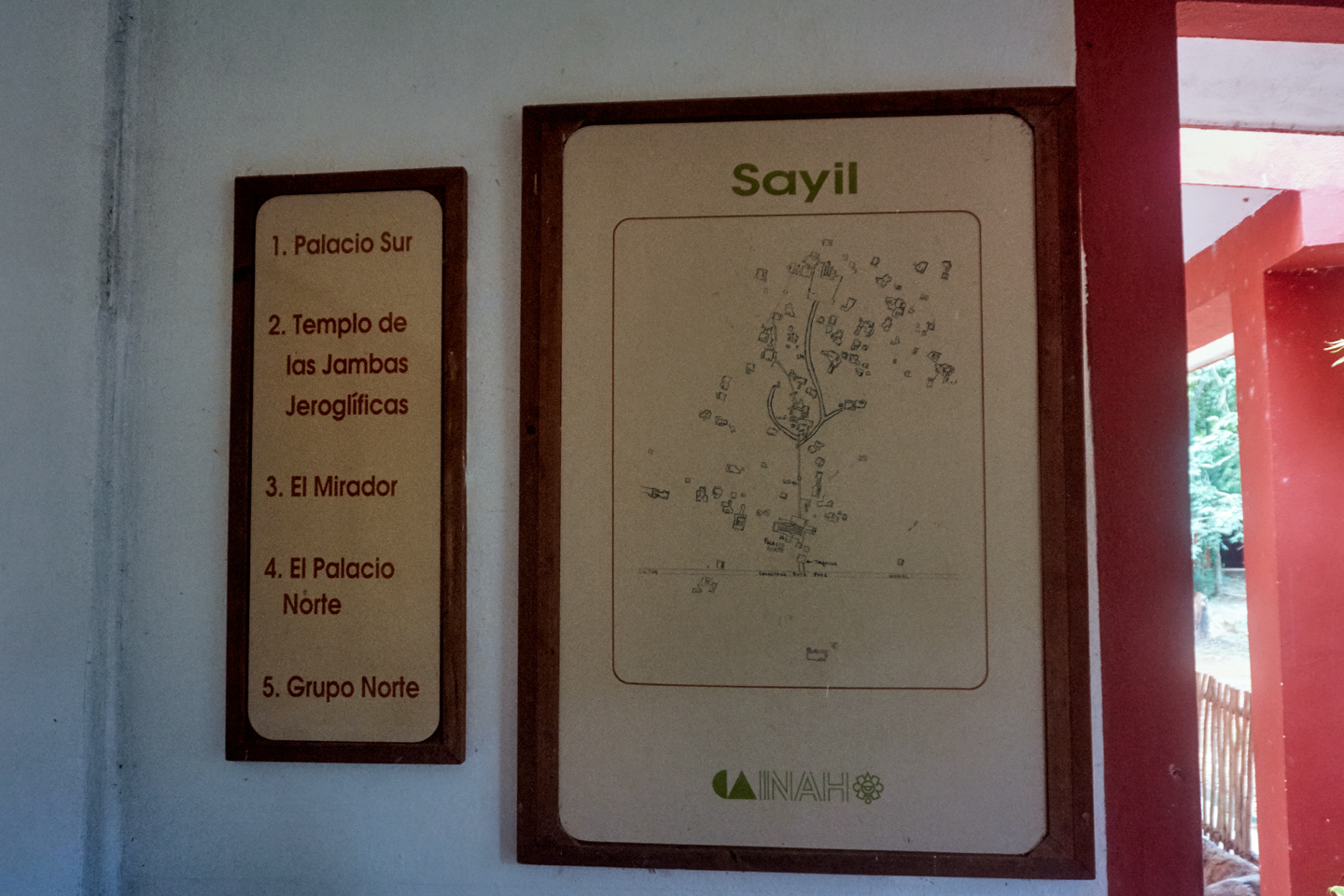

SAYIL

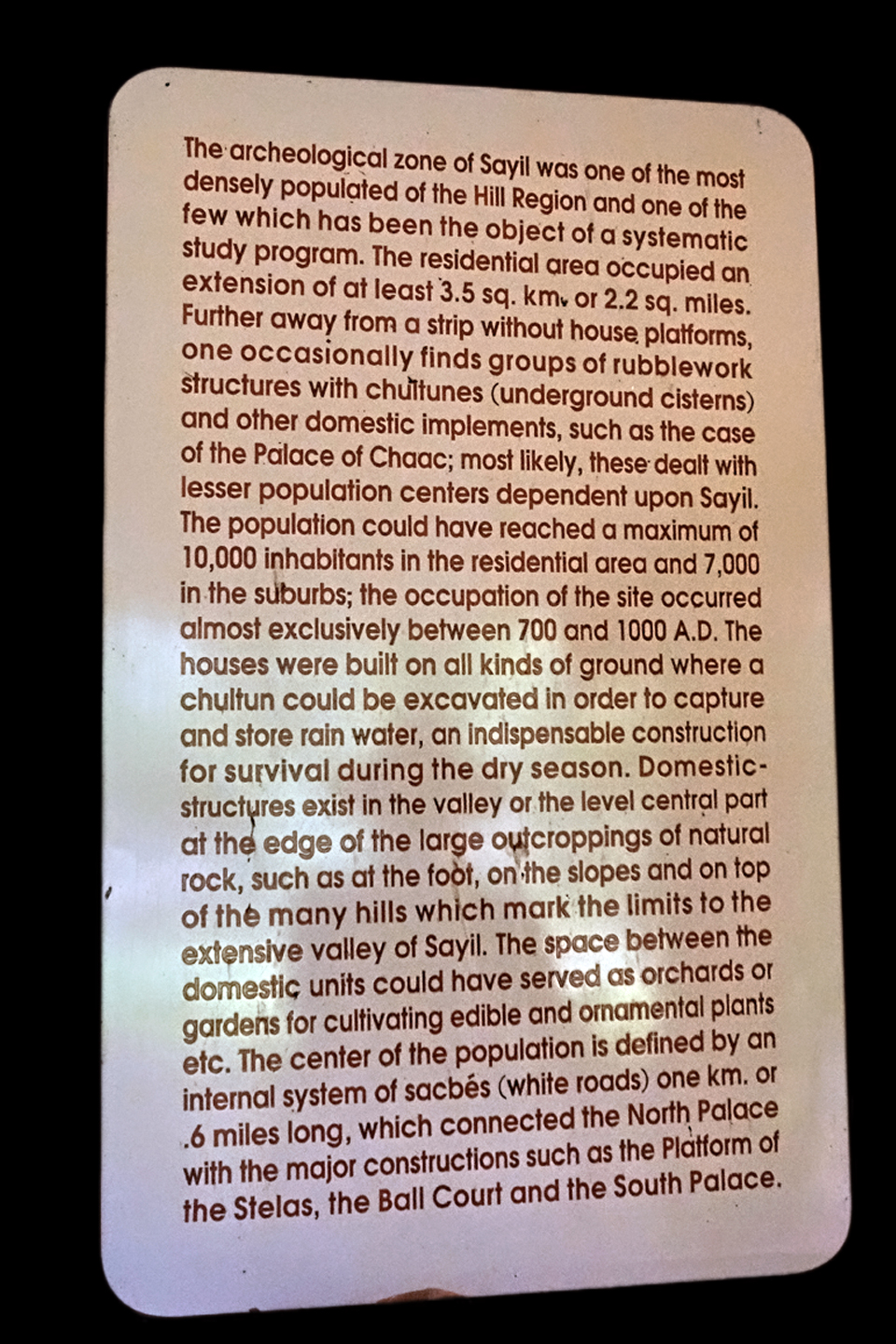

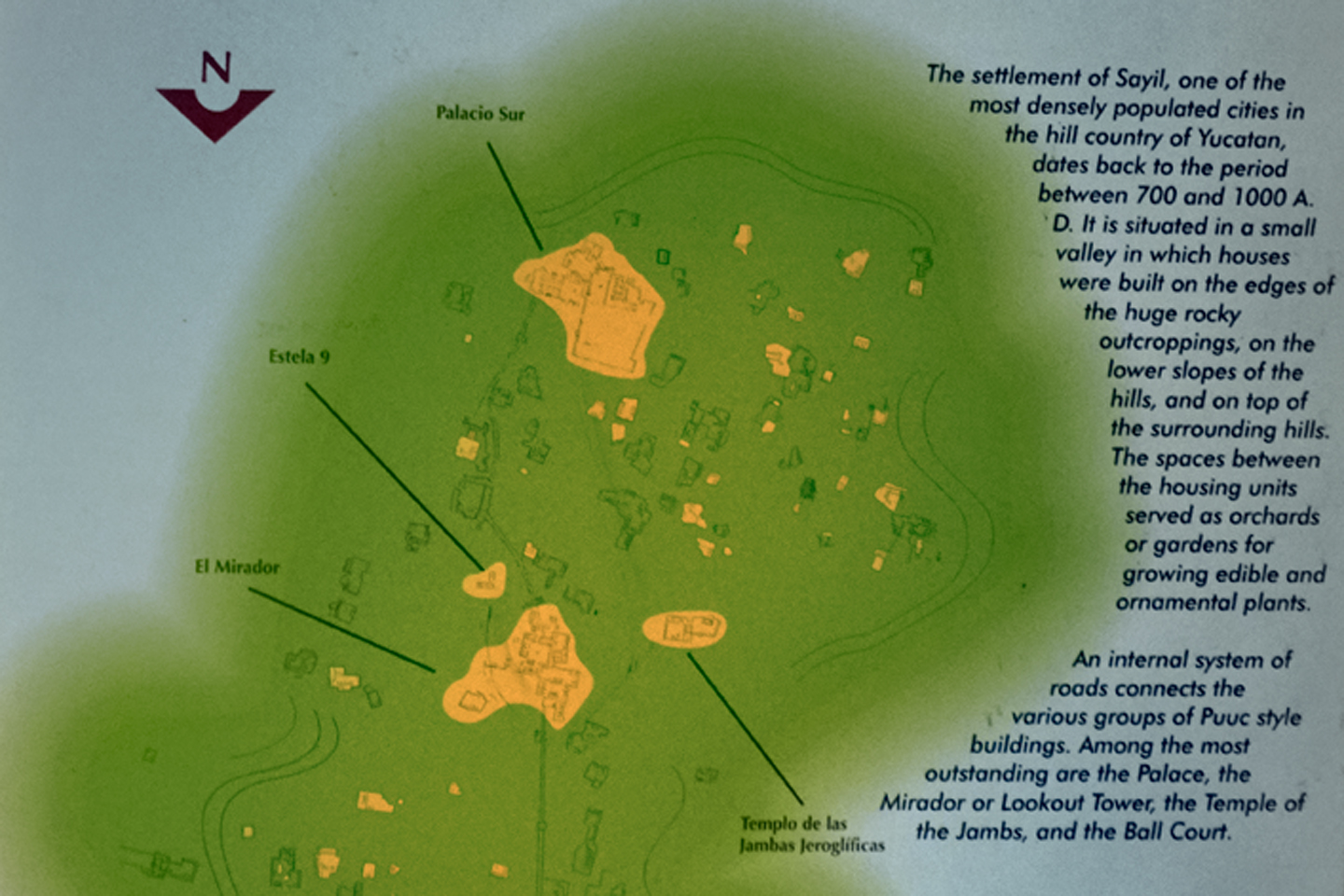

Sayil had a relatively brief history, in the overall scheme of things. It reached its peak around 900 AD, which is when most of the monumental construction took place, and as little as 100 years later, around 1000 AD, the city was abandoned, most likely due to an extended draught that led to widespread famine. At the peak, there were as many as 10,000 people in the area, and without adequate rainfall, it was impossible to grow enough food to sustain them all.

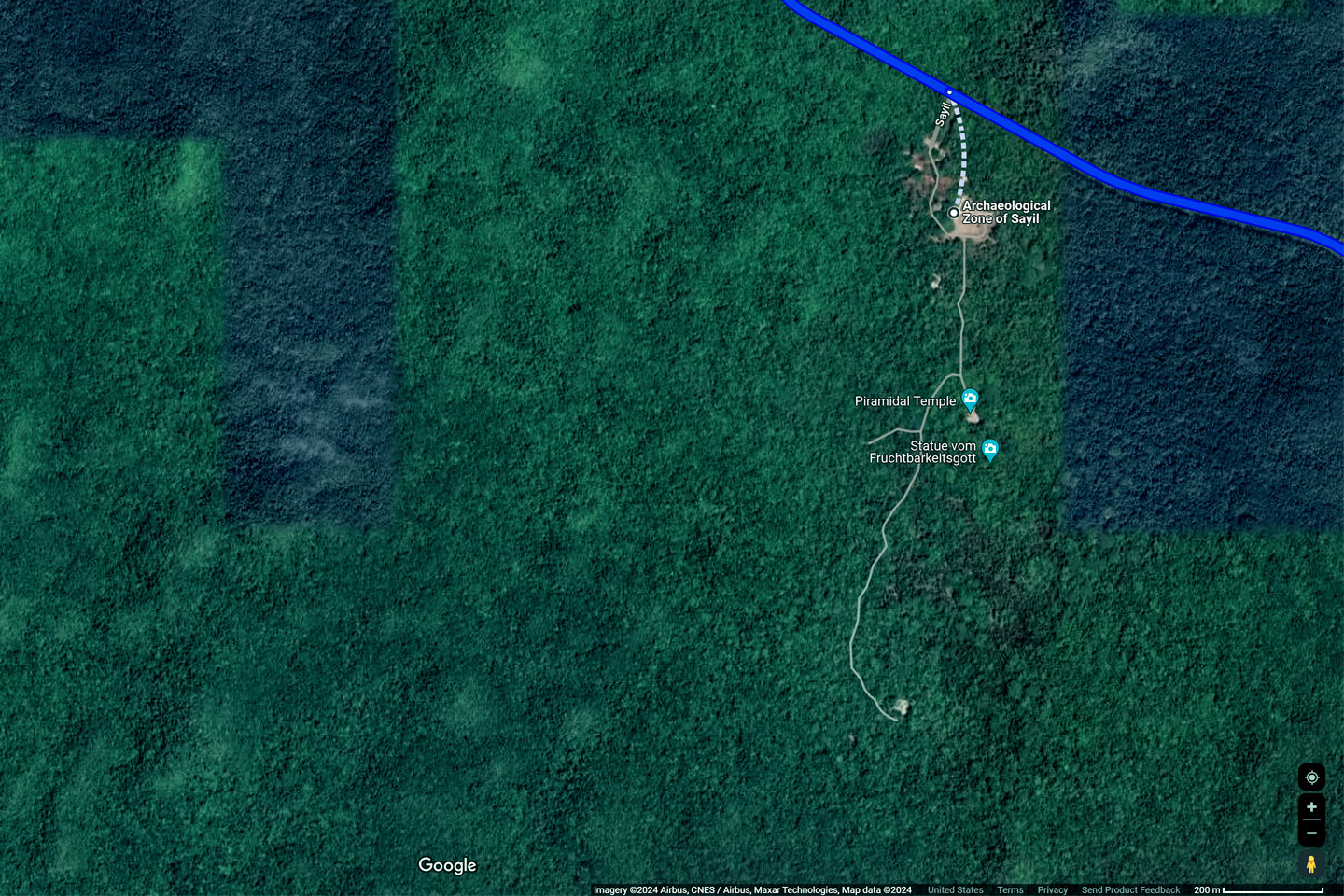

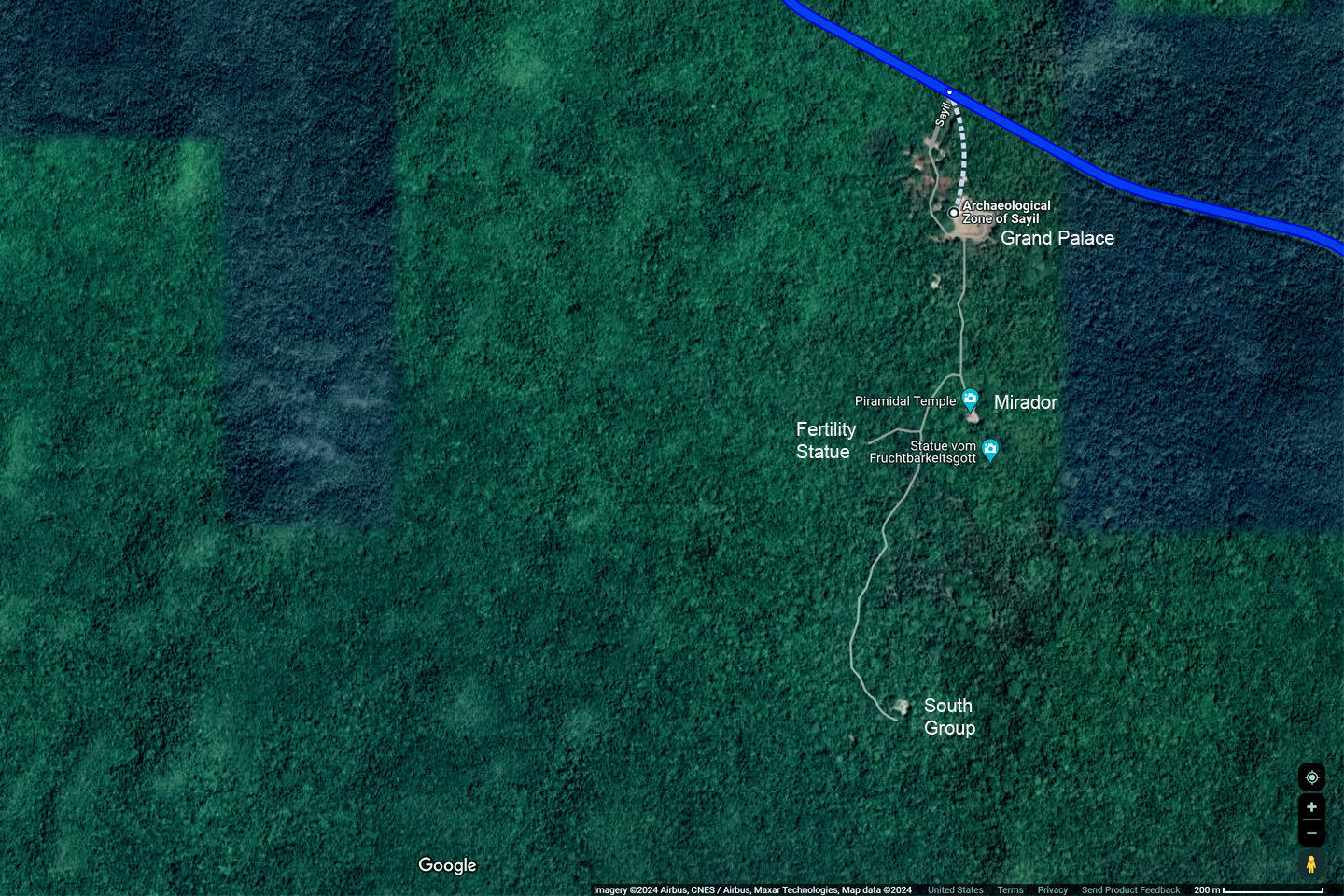

Satellite View of Sayil

Entrance to Sayil

Leafcutter Ants

In the Yucatec Maya language, Sayil means “Place of the Leafcutter Ants,” and it’s easy to see why. For such tiny insects, they are a massive presence in this rain forest. Their nests house as many as two million ants in colonies that extend as much as 50 feet underground. Each worker harvests a snippet of leaf matter, cut with their razor sharp mandibles, and then they get in line, carrying their prize into the nest, where it is used to grow a fungus that is the colony’s primary food source. This activity enriches and aerates the soil, greatly assisting in organic decomposition, a necessary function for maintaining the health of this complex ecosystem.

CLICK PHOTOS TO EXPAND

Most of these photos were actually taken at Labna. Same ants, slightly different neighborhood.

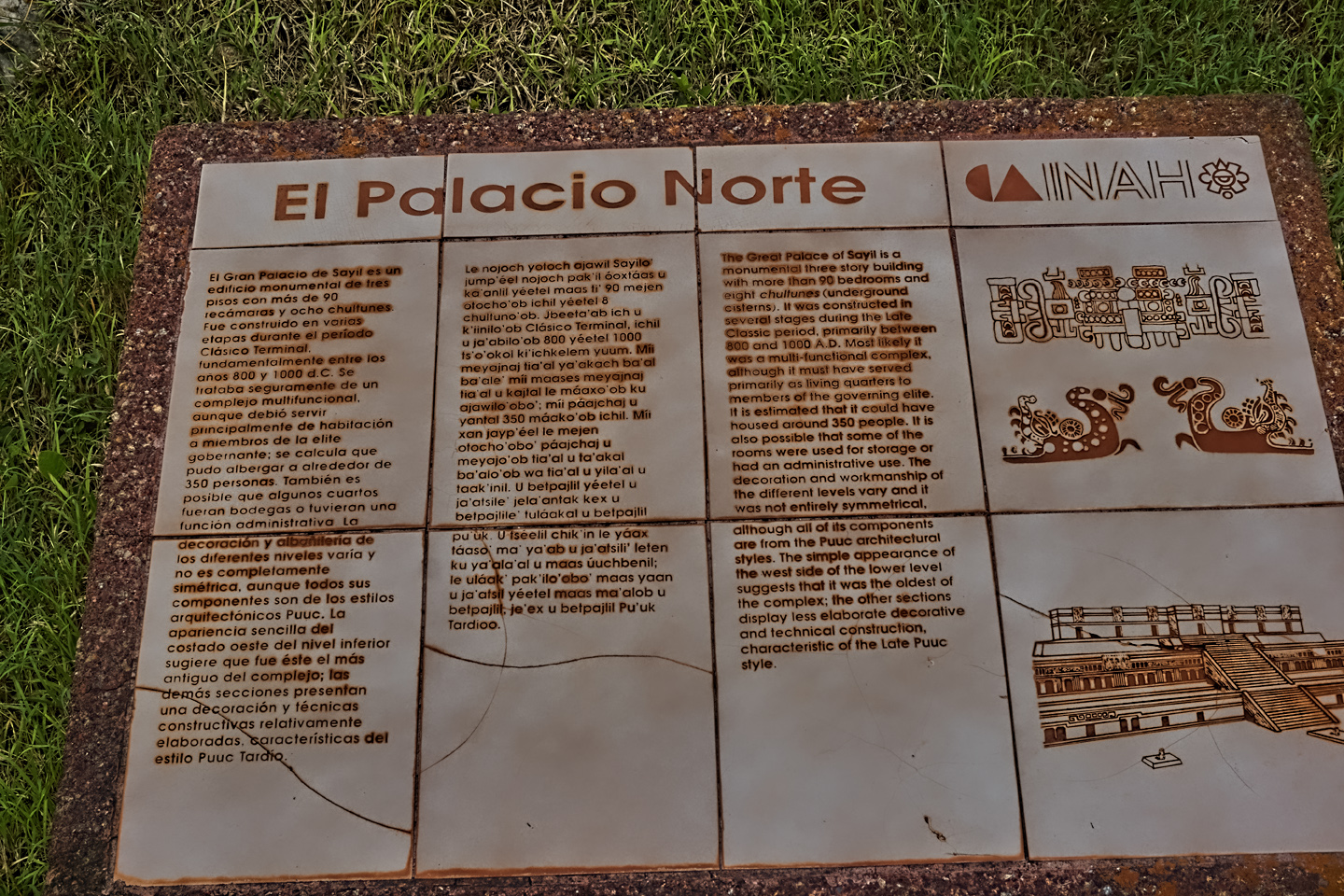

We paid our admission fee in the small building by the entrance, then we followed a path through dense forest to an open area. My first view of the Grand Palace of Sayil was so unexpected, it stopped me in my tracks, and I found myself standing there, mouth agape, neglecting to breathe. “Oh, wow!” I said at last. It was definitely one of those moments.

The Grand Palace of Sayil was an unexpected marvel, giving rise to what I fondly refer to as an “Oh, Wow!” moment.

A carved depiction of the “diving god,” always shown upside down, head-first into a flower, like a honey bee seeking pollen.

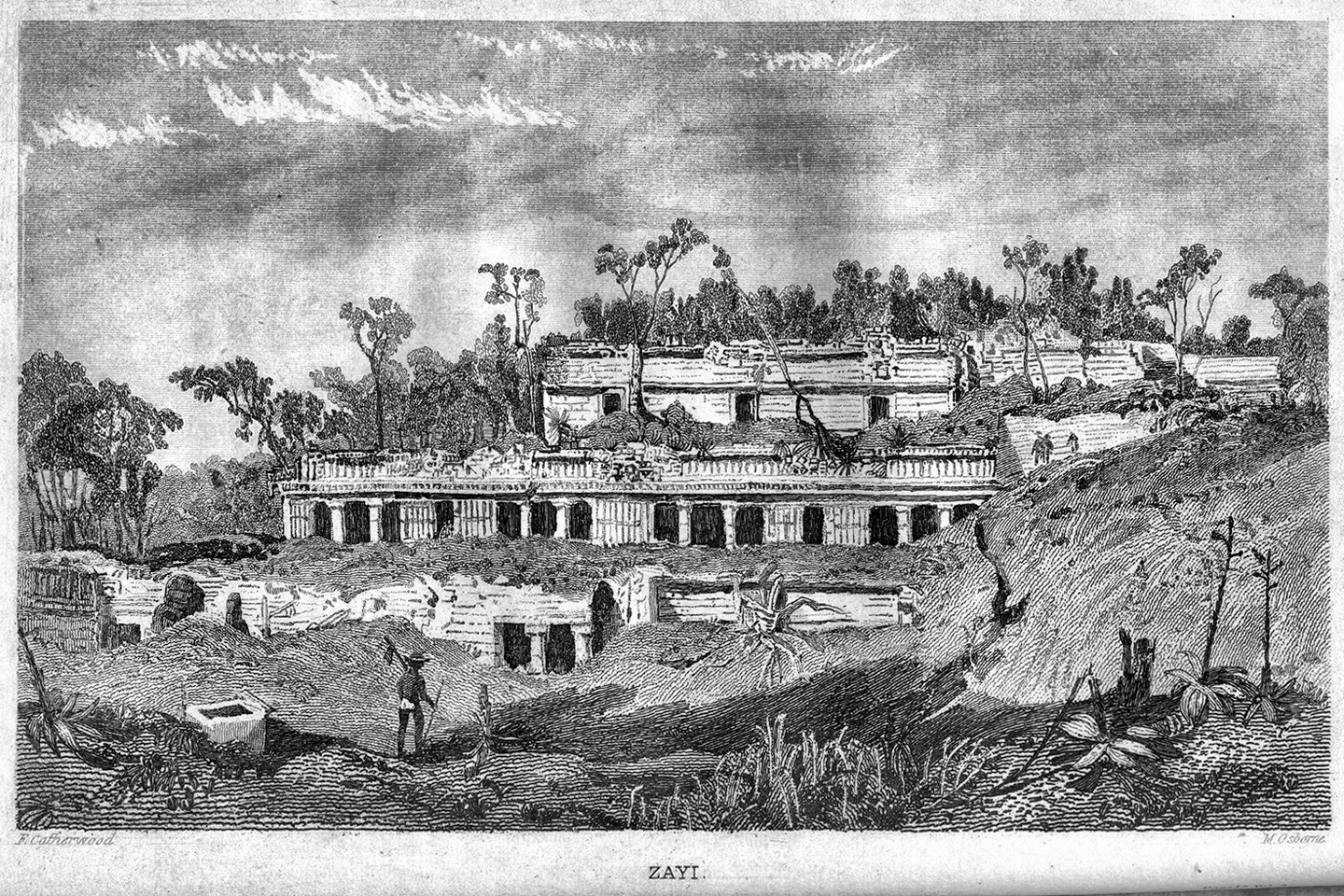

The Grand Palace, or North Palace, is a three tiered structure that’s a whopping 250 feet long, with a 32 foot wide staircase up the front side that leads to the upper floors. Multiple doorways are separated by columns, leading to an interior that boasted 90 rooms. The Palace is a Puuc masterpiece. An engraving titled “Zayi,” by the famed illustrator Frederick Catherwood, appeared in the book Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, published in 1841 by his partner, the travel writer John Lloyd Stephens. Stephens and Catherwood were the first to document many major Mayan cities, including Sayil/Zayi. Their work was an important factor in bringing the Maya to the attention of the world outside Central America.

CLICK PHOTO TO EXPAND, CLICK AGAIN TO ADVANCE

1.) The Palace of “Zayi,” as illustrated by Frederick Catherwood in 1841; 2.) A 19th century photograph of the initial excavation; 3.) B&W photo showing the building as it appears today; 4.) Same image in color

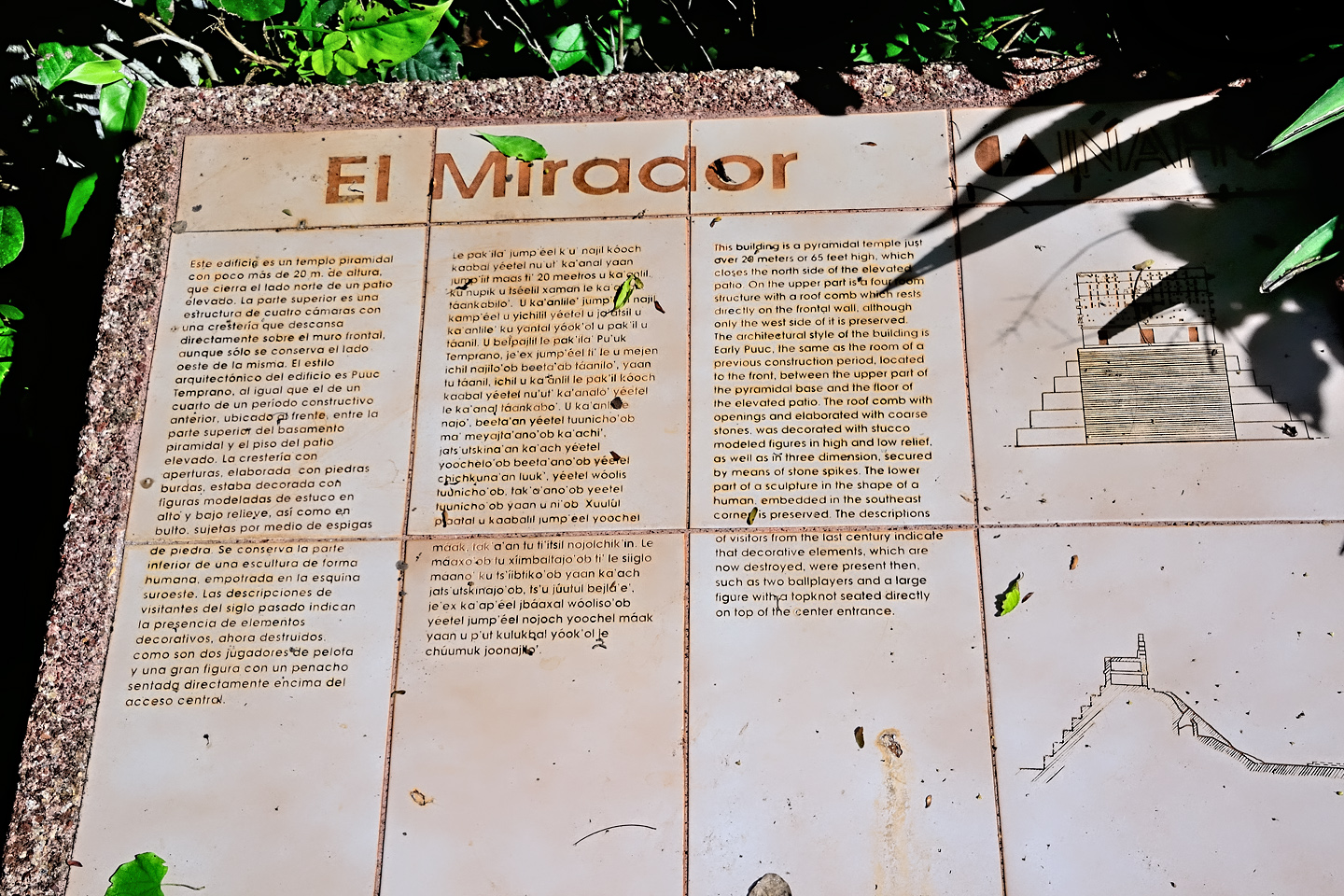

The Mirador, the ruins of a Puuc style Pyramidal Temple at Sayil

There was a sacbe, a raised causeway, leading south from the Palace. We followed traces of that path for 300 yards or so, to the second most famous structure at Sayil, an absolute mess of a temple known as the Mirador, the Watchtower. The most salient feature of this pyramidal temple is the Puuc style roof comb, a well-preserved ornamental structure that runs the full width of the building and rises some 20 feet above the roof. Projecting stones–tenons–were there to support large plaster sculptures. The whole business would have been painted in bright colors, predominantly red.

As for the pyramid, what little is left of it has collapsed, reduced to a grass covered mound of rock and soil that has buried most of the rest of the temple. A single interior room has been excavated and exposed, with open doorways on either side. The pyramid was originally constructed atop a small natural hill, so the temple, especially the roof comb, would have been visible from a distance. Was it an actual watchtower, like a sentry post? Or was it more of a boundary marker for the Palace compound? That whole area would have been considered exclusive, restricted to the elite.

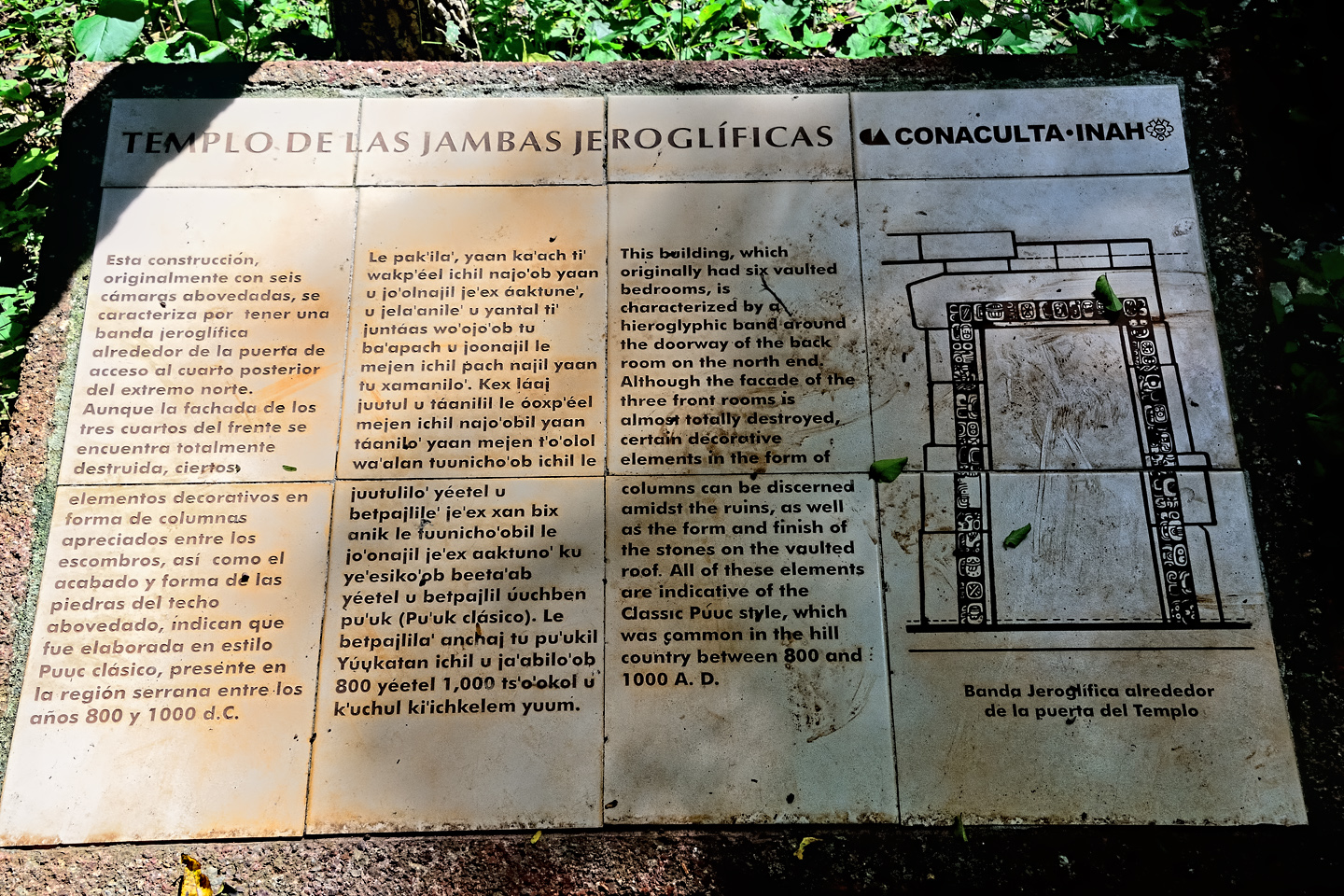

Near the Mirador is a a third structure, very much in ruins, and largely unexcavated. This one is known as the Temple of the Heiroglyphic Jams, a reference to one of the partially buried doorways that is surrounded by a band of glyphs. The temple is overgrown by tropical vegetation, and it’s very easy to imagine what the whole place, including the Grand Palace, must have looked like to the first explorers who came across these ruins. Lost cities in the jungle, rising from the mists of time. Such is the mystique of the ancient Maya.

The Temple of the Heiroglyphic Jams

Signs and site maps at the entrance to Sayil.

Sayil is surrounded by rain forest, closing in on all sides.

Mike and I had fallen into a routine of sorts during our visits to these archaeological parks. I’d always make a beeline to the big stuff, the iconic views, the perspectives likely to make the most impressive photographs. Mike, on the other hand, liked to move at a calmer, more deliberate pace, soaking it all in. I have a degree in anthropology, and I studied the Maya in school, so my perspective on all this stuff was quite different from his. We would often split up, each of us doing our own thing, and then we’d regroup. I never really worried about us losing track of each other, but at Sayil, this approach turned into a problem. After the Mirador, I went on ahead while Mike took some close-ups of flowers, or fungus, or some such thing. I came to a fork in the path, and took a right, walking as far as a group of stelae, standing stones. Then I got distracted, taking photos of a bizarre sculpture of a Mayan couple locked in an embrace, with the man sporting an enormous phallus (see photo, above). A few minutes later, I was ready to leave Sayil. We’d seen the best of it, and we had three more sites to visit, so we needed to get a move on. I looked around for Mike, but didn’t see him anywhere, so I shouted his name. No answer. I followed the path back past the fork to the Mirador, shouting as I walked along. Nothing. Back to the Grand Palace, where I shouted even louder, many times, before walking all the way to the building where we bought our tickets. I asked if anyone had seen my friend, but they had not. Not since we came in together. I tried calling his cell phone, but there was no signal in that place.

Back into the ruins I trudged, shouting myself hoarse, and getting a bit worried. I walked completely around the Grand Palace, hollering my head off, but no Michael. Back to the Mirador, same deal. At that point, I hadn’t seen Michael in at least an hour, and I was ready to call in an actual search party, imagining the poor guy passed out on the trail, or worse! I came to that fork in the path, and I spotted a small sign I hadn’t noticed before. It read “South Group,” with a pointing arrow. I started down that path, calling for Michael as I walked along, but after a few minutes of that, I stopped. I was sweating buckets, and I was frustrated as hell, so I took a deep breath and yelled as loud as I could, put everything I had into it, and this time, Mike not only answered, he appeared, strolling up the South Group path, casual as you please. I won’t transcribe what I shouted at that point. Let’s just say it wasn’t very nice.

Satellite map, showing relative location of the South Group

It seems Mike had followed the signs to the South Group, a cluster of ruins that was a good two kilometers away from everything else. (See satellite map, left/above). He hadn’t realized it would be that far, so he simply kept going (and going, and going). It took him almost half an hour to reach the end, and another half hour to get back. He’d been expecting me to follow him, surprised that I hadn’t, though, by his own admission, the structures in the South Group weren’t anything special, not really worth the hike. I pointed at my watch. It was almost 3:00, leaving us just ninety minutes to visit three more sets of ruins? Quite simply, that wasn’t going to be possible.

I was furious, but there was no sense in taking it out on Mike. I had to blame myself, for not being more emphatic about our time constraints, and for not keeping closer tabs on him. Michael doesn’t wear a watch. That’s not the way he rolls.

Without belaboring the point, we beat feet back to the parking area, jumped in the Jeep, and headed off down the road to our next stop. Even though we were running low on time, I was determined to make the most of what we had left.

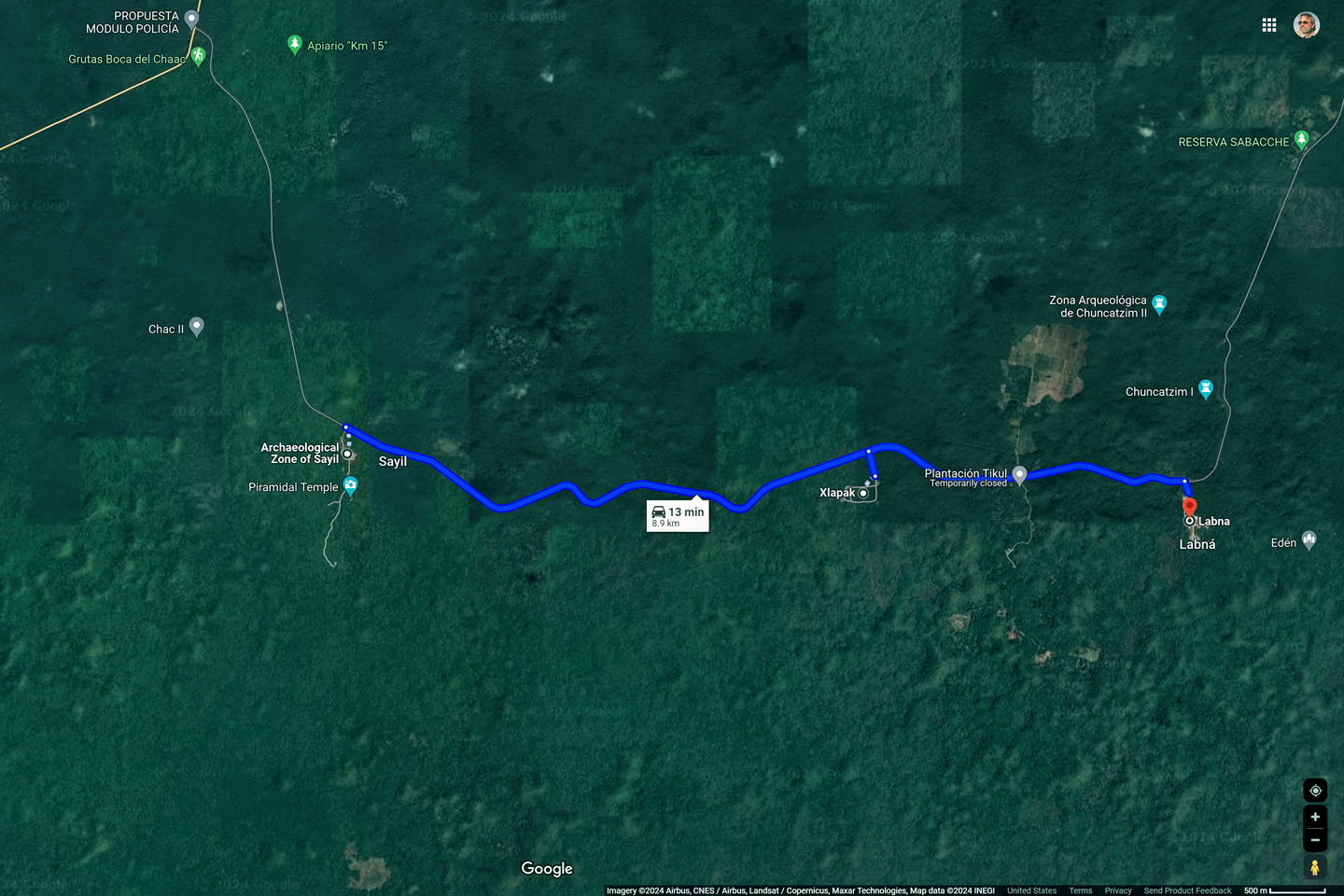

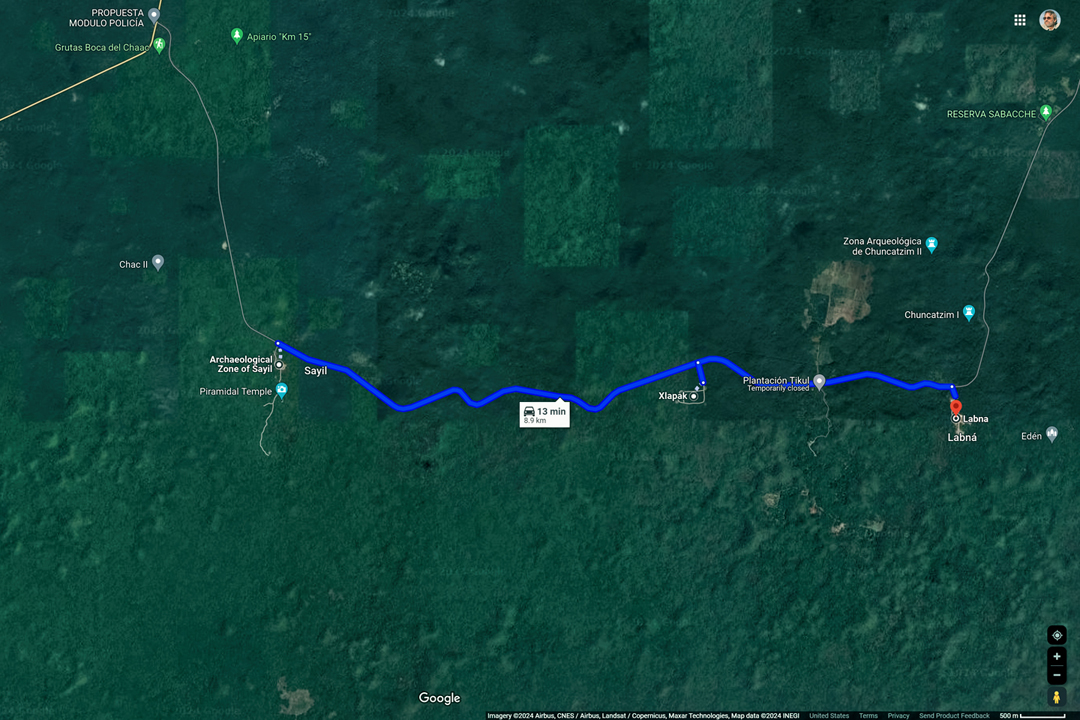

The road between Sayil, Xlapak, and Labna.

According to our map, Xlapak, the smallest of the Puuc Route sites, was just 3 miles up the road from Sayil, and Labna was two miles further.

I wanted to stop at Xlapak first, so I kept an eye on my odometer. We passed Mile 3, and then Mile 4, but there were no signs of any kind, and I started to wonder if we’d missed it somehow. The road was very narrow here, with no shoulder, like a country lane. I kept driving, and after another mile or so, I finally came to a sign: “ZA Labna,” (for Zona Arqueologica). We turned down an even narrower road, finally arriving at a tiny parking lot.

Labna: Entrance sign

LABNA

Apparently, we’d driven right past Xlapak, but I figured we could look for it again on our drive back out. We bought our tickets for Labna, and I could see from the site map that the park was relatively compact. There was a palace near the entrance, connected by a sacbe to a cluster of monuments, including a pyramid and an arch. One of Frederick Catherwood’s best known engravings featured that very structure, the “Labna Arch,” and I was curious to see how the real thing compared to the 19th century art work.

Satellite view of Labna

Site map

The Labna Arch in 1842, a drawing by Frederick Catherwood.

Labna, which means “Old House” in the Yucatec Maya language, has been joined to Sayil, and, by extension, to Uxmal, through most of its history. Like Sayil, it’s a Late Classic site that flourished from 600 AD to 900 AD, and the architectural syle of it’s monumental structures is pure Puuc. The population declined around 1000 AD, but the city wasn’t totally abandoned until around 1200 AD, 200 years later than Sayil. Like Sayil, the first published reports of the ancient city were from Stephens and Catherwood, back in the 1840’s. Also like Sayil, it is a part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site that incorporates Uxmal and the Puuc Route.

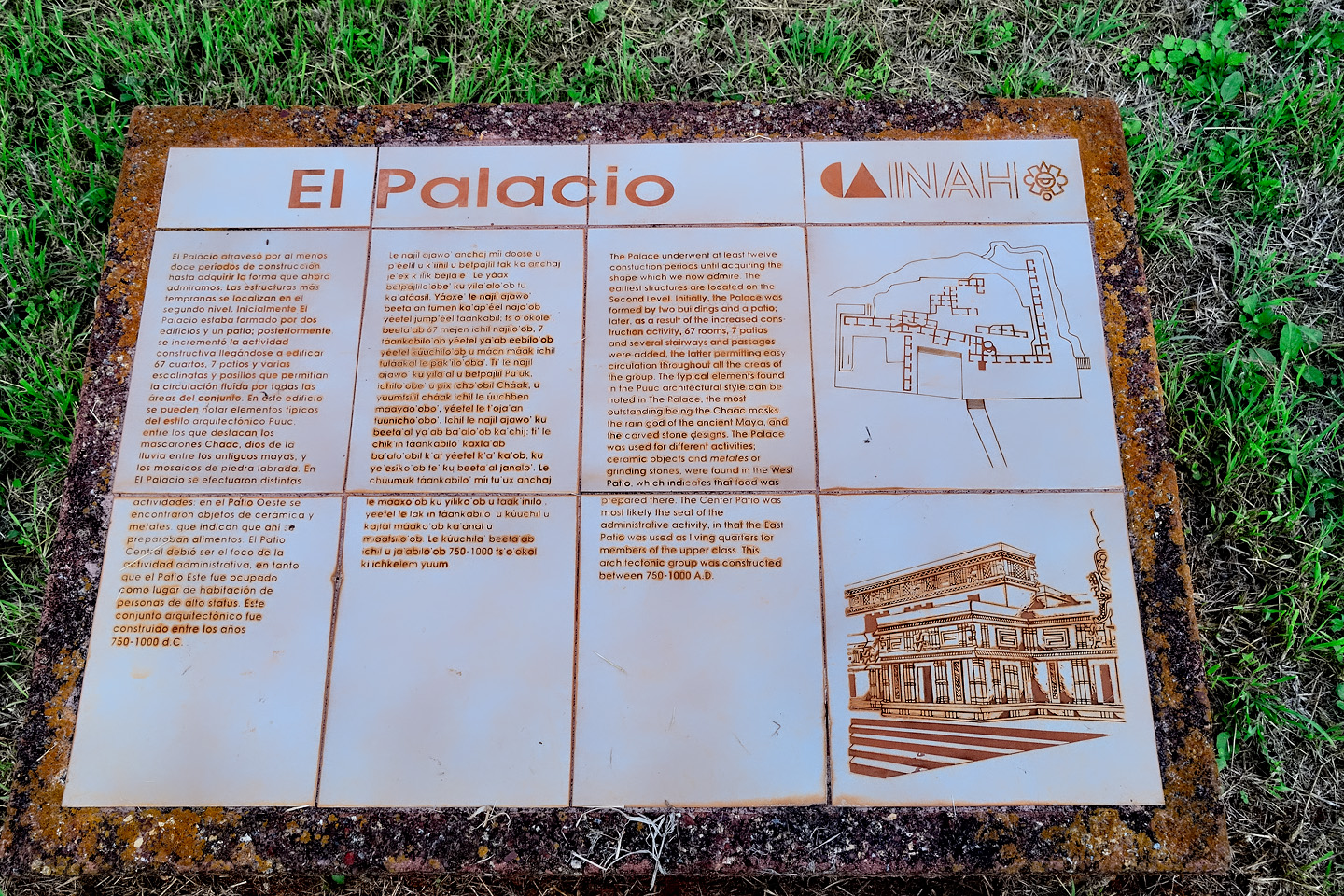

Walking in, the first thing we saw was the huge building they call the Palace, a two story structure with a wing added to each end, bringing the total length to almost 400 feet, the longest such building in the Puuc region. The lower walls feature square cut stones set into a concrete core, forming a smooth veneer, while the upper walls feature a cornice comprised of cut stone carved into rows of columns, alternating with carved geometric shapes, assembled into mosaic panels. Included are several depictions of Chac, the big-nosed god of Rain. These are all classic elements of Puuc Architecture.

Leading due south from the Palace was a sacbe, a raised causeway bordered by low stone walls on either side. I told Mike to stick close as I followed that path to the ceremonial plaza, where we got our first look at the Labna Arch:

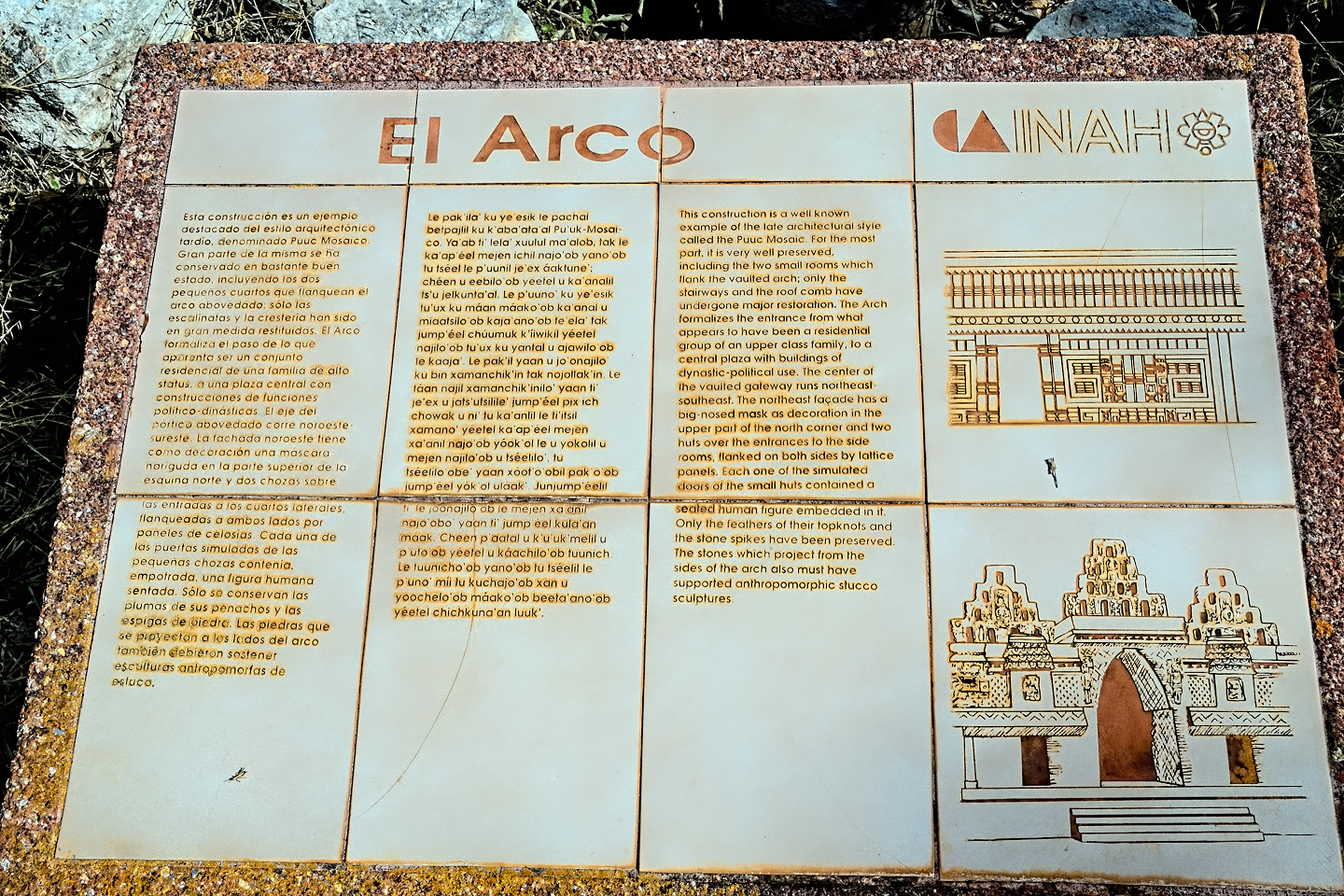

LABNA ARCH

Like the Grand Palace of Sayil, the Labna Arch was a stunner, every bit as impressive as the famous engraving by Frederick Catherwood. The walls that once stood on either side of the arch are depicted in his drawing, but in the 175 years that have passed since his visit, they’ve fallen, leaving the arch standing alone. It’s what’s known as a corbeled arch, as opposed to a true load-bearing arch. The Maya never quite figured out the concept of a keystone, a wedge-shaped stone carved to fit at the top of an arch, where it’s locked in place by the equal weight of both sides. Even without the keystone, arches like this one were quite solidly constructed, and it’s not uncommon to see them still intact, after the rest of the wall or building to which they were once attached has long since crumbled to the ground. The Labna Arch was not a gateway into the city. Rather, it was a passage between two distinct segments of the ceremonial complex.

The Mirador, a ruined pyramidal temple similar to the Mirador at Sayil

On the other side of the arch there was a ruined pyramid, crowned by a cube-shaped temple with a prominent roof comb. It’s called the Mirador, just like the Watchtower at Sayil, and the pyramid part of the structure is in similarly poor condition. To put it crudely, what’s left of it is little more than a pile of rocks. The stucco facing that once covered the sides is gone, leaving nothing but the stacked stones at the core. Like the Mirador at Sayil, the roof comb would have supported plaster sculptures or bas reliefs, painted in bright colors, and visible from a distance.

Labna was small enough that we really didn’t need a lot of time to see it. The major structures, the Palace, and especially the Arch, were unique, and they were some of the finest examples of Puuc Architecture to be found anywhere. The same could most certainly be said of the Grand Palace at Sayil. These small cities are like the Mayan version of suburbs, satellites of the big town, in this case, Uxmal. All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

Scenes in and around the ruins of Labna.

It was almost 4:00 PM when we left Labna. We were facing a two hour drive back to Campeche, and sunset happens at 6:30. The math was pretty simple: we had to be on the road and headed for the barn in just 30 minutes, or we’d be driving MX 261 in the dark. Kabah was obviously out of the question, but we might be able run in to Xlapak, snap a couple of photos, and run back out, just so we could say we’d been there. Of course, that was assuming that we could FIND Xlapak. On the drive from Sayil to Labna, we hadn’t seen hide nor hair of the place. This time, we spotted an unmarked side road, close to where the ruin was supposed to be, so we turned down it. After about 100 yards, we spotted a sign that said Xlapak, and just beyond that, a tiny parking lot.

An unmarked side road between Sayil and Labna leads to Xlapak. (Map and street view photos courtesy of Google)

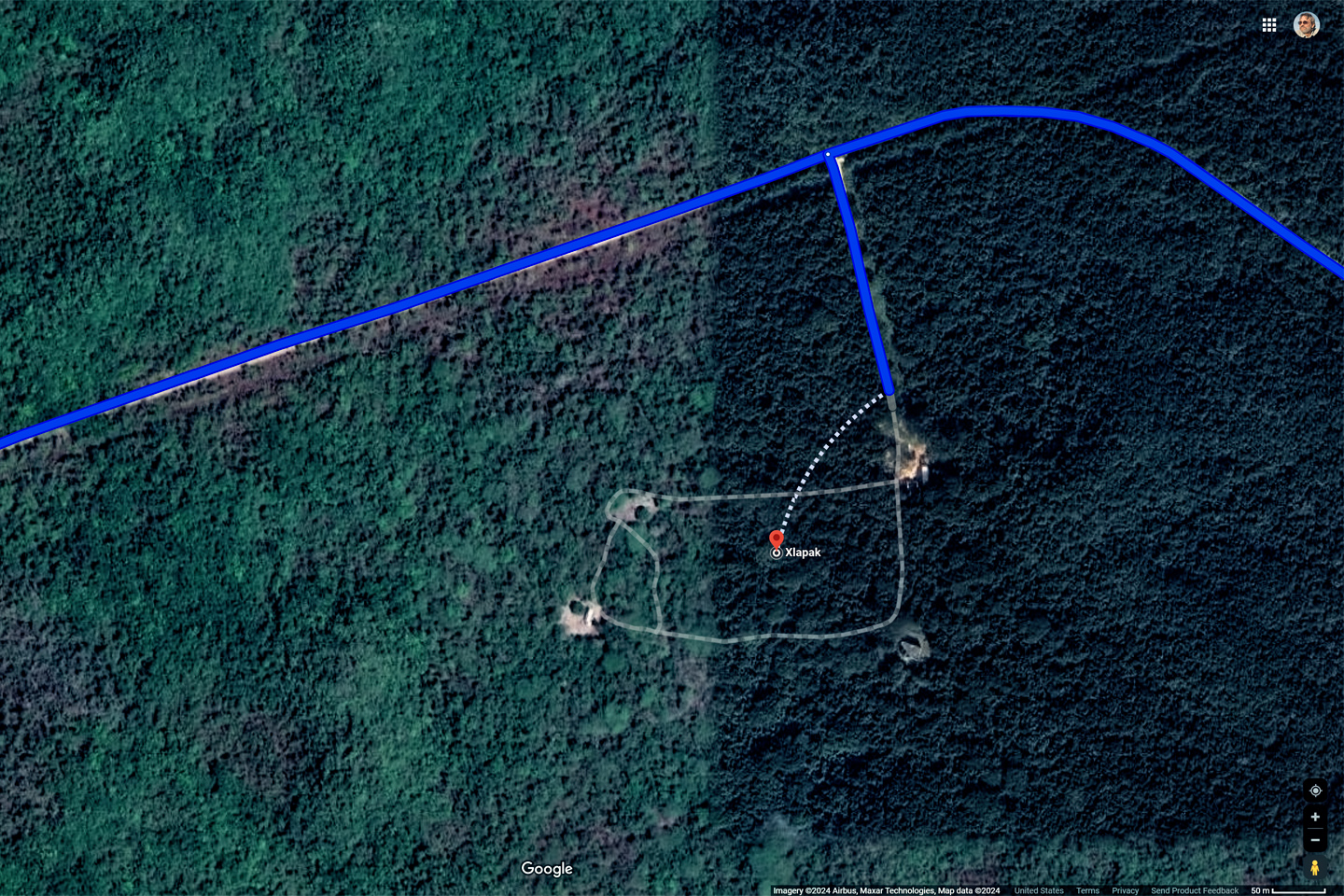

XLAPAK

By then it was 4:10, and according to the man in the ticket shack, Xlapak closes at 4:30, rather than the usual 5:00 PM. Since we only had 20 minutes, he let us go in for free, but we had to swear on our mother’s graves that we would hustle back out by closing time. (The guy told us that he had a hot date waiting for him in Santa Elena, and he didn’t want to be late!) I’m not going to say we ran, but we definitely hustled, following the caretaker’s brief instructions: down the path from the entrance, and straight ahead when we came to the fork. A five minute walk, at the most, to Xlapak’s version of a Palace.

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS TO EXPAND

Several views of the Palace at Xlapak, on the Puuc Route

The Palace, Xlapak’s only structure of any size, is a tiny thing when compared to the Palaces at Sayil and Labna. The building is so top heavy with Puuc style bric-a-brac, it’s a surprise that it hasn’t collapsed under its own weight. Each corner features stylized depictions of Chac, the god of rain, stacked three high, and at the front and rear of the building there are super-sized Chacs, large square mosaics, comprised of individually carved stones, assembled like pieces of a puzzle, and cemented in place. We walked a little further to a second structure, this one an unreconstructed pile of rubble, and that was pretty much it for our visit to Xlapak. The caretaker locked the gates behind us as we left; I shook his hand, and thanked him for the favor of letting us dash in at the last minute.

Since we arrived at Xlapak just before closing time, they only gave us ten minutes to see the ruins. The site is so small, that was all we really needed!

WHAT WE MISSED:

The Mayan City of KABAH

Probably my biggest regret on our whole amazing road trip. We passed within five miles of Kabah, but we didn’t budget enough time to so much as stick our noses in the door. Kabah is the second largest Mayan city on the Ruta Puuc (after Uxmal), and it features many one-of-a-kind monuments. If we’d stuck to a schedule, we probably could have fit it in, but what the heck–we still had plenty of fun! (That said, if I ever revisit the Ruta Puuc, I’ll make a point of stopping at Kabah FIRST!)

Images borrowed from the Internet

A FAST RUN BACK TO CAMPECHE

Scenes along the road in Bolonchen, Campeche

Driving back, we were in a race against time and a setting sun, but this was not a road that could be driven fast, so the only way to get an edge was to drive it efficiently. We passed through Bolonchen, which I remembered from before. The shadows were already getting longer, the townspeople winding out their day.

As we drove along the narrow streets of their little down town, people on the sidewalks all started pointing, but they weren’t pointing at my Jeep, they were pointing down the road, back the way we came, and some of them were shouting.

“What’s going on?” I asked, peering under the visor, blinded by the sun in my eyes.

“I dunno,” Mike replied, sticking his head out the window to see behind us. “Wait–oh, crap!”

“What?” And then I saw it. We were going the wrong way on a one-way street! A car coming toward us started blowing his horn, so I whipped around the first turn that we came to, and spent five minutes driving in circles before we reconnected with MX 261, pointed in the proper direction. So much for driving the road efficiently!

Back out on the highway, we made much better time, because there was very little traffic. At one point we overtook a small pickup truck, and when we pulled up alongside, I counted 19 people packed into the back, standing room only, plus three more in the cab. They gave us a friendly wave as we passed them. I shuddered to think what would happen if that truck failed to slow down for a speed bump, or braked too hard for a cow or a stray dog!

Ride sharing, Campeche style!

Hopelessly lost in Hopelchen

By 5:30, we’d made it as far as Hopelchen, close to the halfway point, and not far from Tohcok, the little bonus ruin we’d stopped at earlier in the day. That meant we were doing okay, timewise–until we entered the town. Highways don’t always run in a straight line through small towns in Mexico. The required turns don’t always seem logical, and signs are often missing at critical road junctions. That’s okay for locals. They all know where to go. As for Me and Mike? We got sooo lost!

I wouldn’t have thought it possible to get so turned around in a town that small, but it was all narrow, one way streets, and none of them seemed to go through beyond the downtown. Hopelchen (Hopeless-chen) made our wrong-way adventure in Balonchen (Ball and Chain) seem like a minor blip in comparison. We lost the best part of ten minutes just getting out of there–and it was time we did NOT have to spare! Funny thing was, we’d had no problem driving through that same town earlier in the day, while headed in the other direction. Now, because we were in a hurry, Murphy’s law kicked in on us, and we made nothing but wrong turns.

Scenes in and around Cayal, Campeche, getting late in the day!

6:00 PM! We passed through the tiny town of Cayal, with the sun dropping lower every minute. We had 30 miles to go, and half an hour until sundown. On any modern road, this wouldn’t have been a problem, but on MX 261, it was like the impossible dream. I drove as fast as I dared, making up a little time on the open stretches, but the closer we got to Campeche, the more people we encountered, and the more people, the more topes!

I put Mike in charge of Speed Bump Spotting, and working as a team, we managed to avoid most of them. Once or twice, his shout of TOE-PAY! came too late for me to slow down, and we hit those suckers, KA-BAM! Hard enough to rattle our teeth, and send our luggage flying. I never blew any tires, hitting topes at speed, but there was cumulative damage to my front end: control arms, bushings, steering components, shocks. I suspect that the repair shops in Mexico that do that kind of work must have more business than they can handle.

We rolled into Campeche about 6:45, parking in the lot by our hotel just as dusk faded into darkness, and the lights of the city came on. We freshened up in our room, and then went out on the town for a seafood dinner (giant shrimp, as I recall), followed by a stroll around the old town, and the central plaza. The afternoon and evening of the previous day we’d watched an amazing “Festival of Dance and Folklore” right there in the plaza. This evening, it was a light show!

Campeche is one of the most colorful cities in Mexico, with storefronts and houses in the historic sector painted in a dozen shades of pastel. That night, they kept that theme going with a colored light show in the plaza. Multi-hued spotlights focused on a long row of arches. Colors shifted, messages flashed, and then a series of portraits appeared, people from the town, each arch framing a different face.

On the other side of the Plaza, colored spotlights illuminated Campeche’s historic Cathedral, a play of light and shadow against a sky that was dark with clouds, save for one spot, where an almost full moon shone down through a small break in the overcast. With the spotlights and the portraits on one side, and the brightly colored cathedral on the other side, Campeche’s Plaza was a psychedelic trip!

We’d had an exhausting day. Almost five hours of driving, four sets of Mayan ruins, several miles of walking (most of that at Sayil). We already had our plan set for the next day: we were going to drive back to Palenque, and from there we were going to visit one last Mayan ruin, a place called Bonampak, near the border with Guatemala, famous for remarkably preserved painted murals. After Bonampak, assuming the roads were clear, we’d cross the mountains to San Cristobal de las Casas before beginning our journey back north. We’d already seen so much, it was hard to believe we’d only been on the road for 16 days. We were past our halfway point, but we still a LOT to look forward to!

The collage below features additional photos taken on the road in Mexico by my inestimable shotgun rider, Michael Fritz. (Michael is responsible for many of the photos in this series of posts). Click any image to expand them to full screen:

(Unless otherwise noted, all other images are my (or Michael’s) original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen

Michael Fritz, “Elmo,” 1949-2025

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

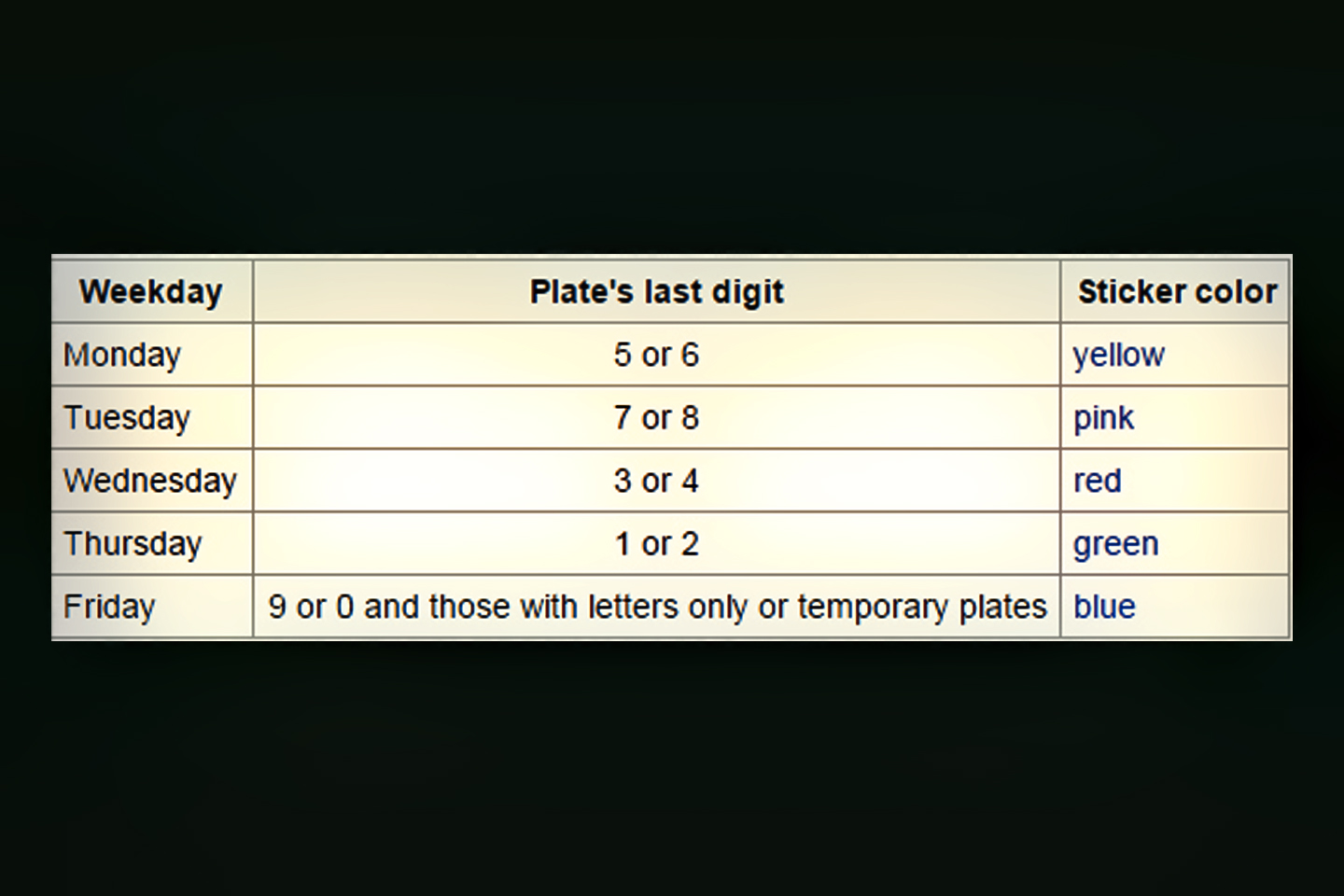

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

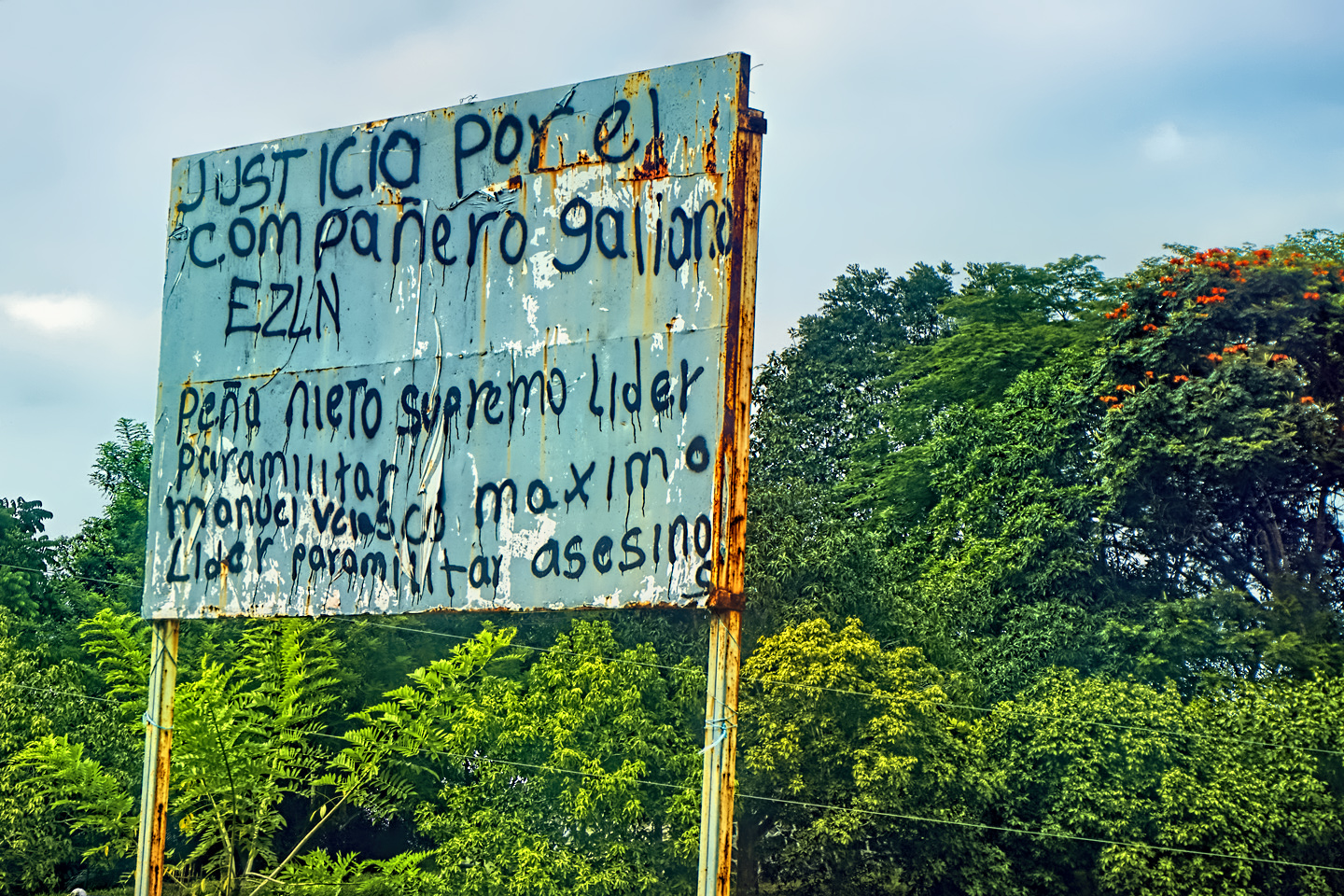

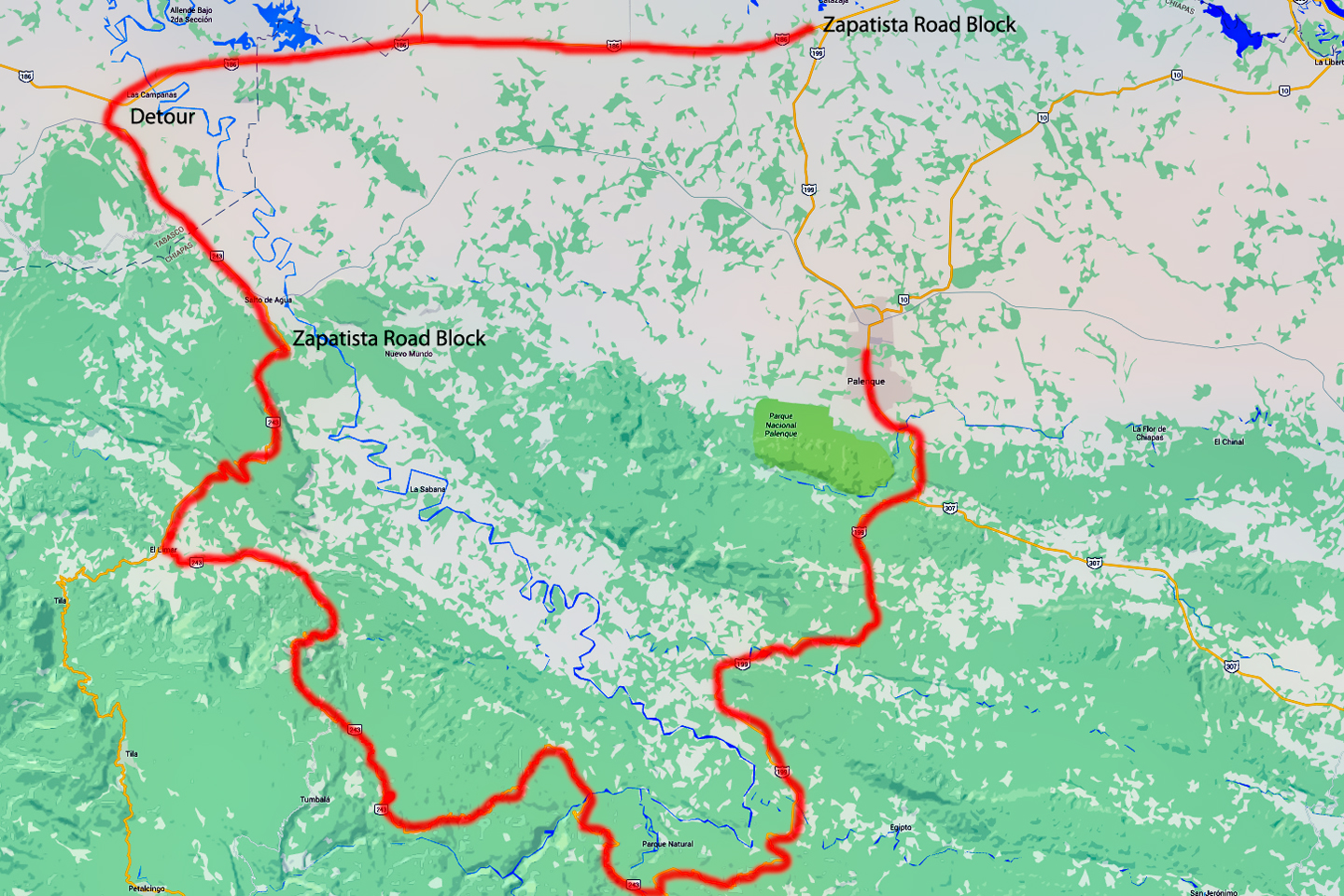

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

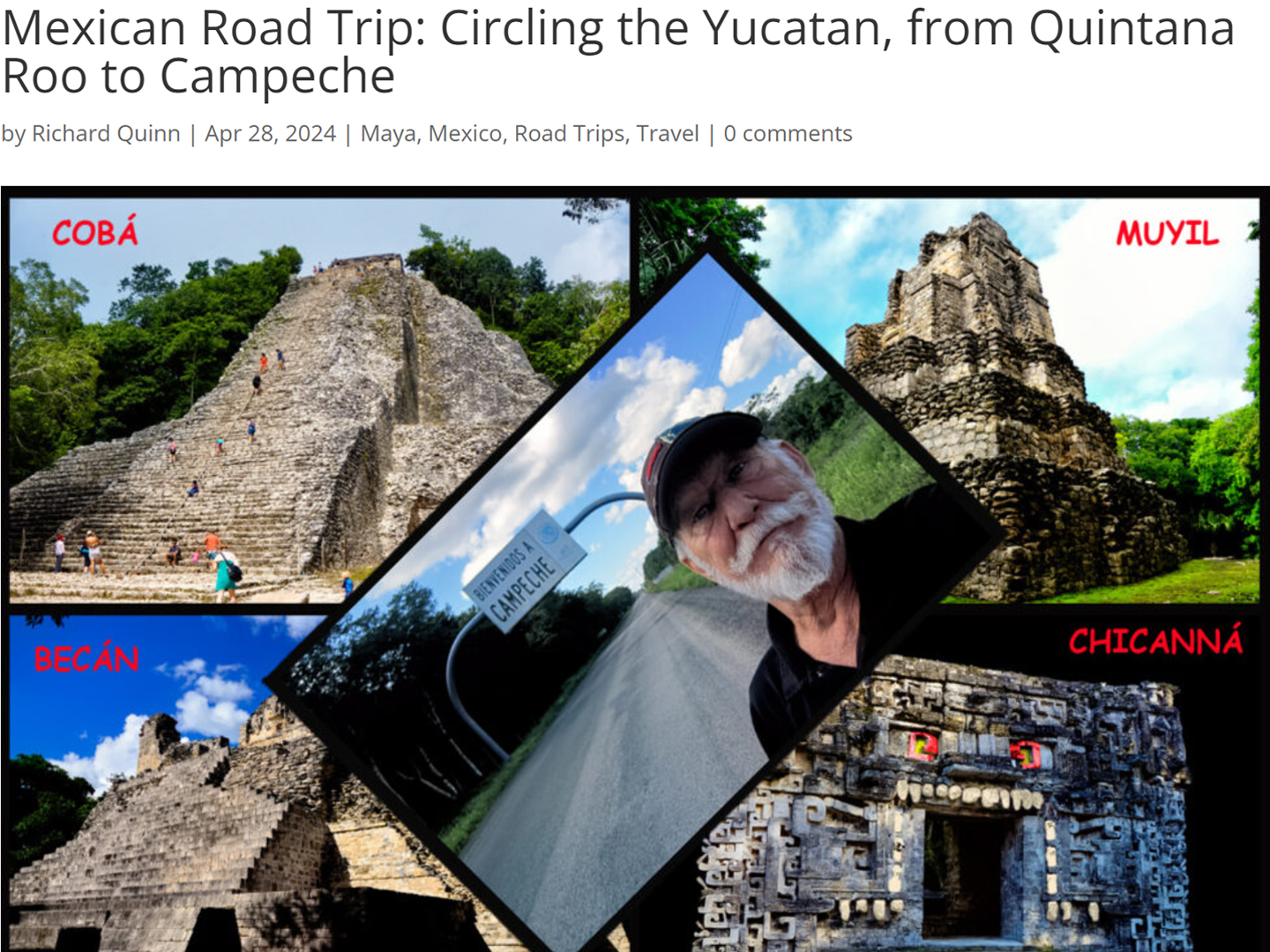

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn't huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

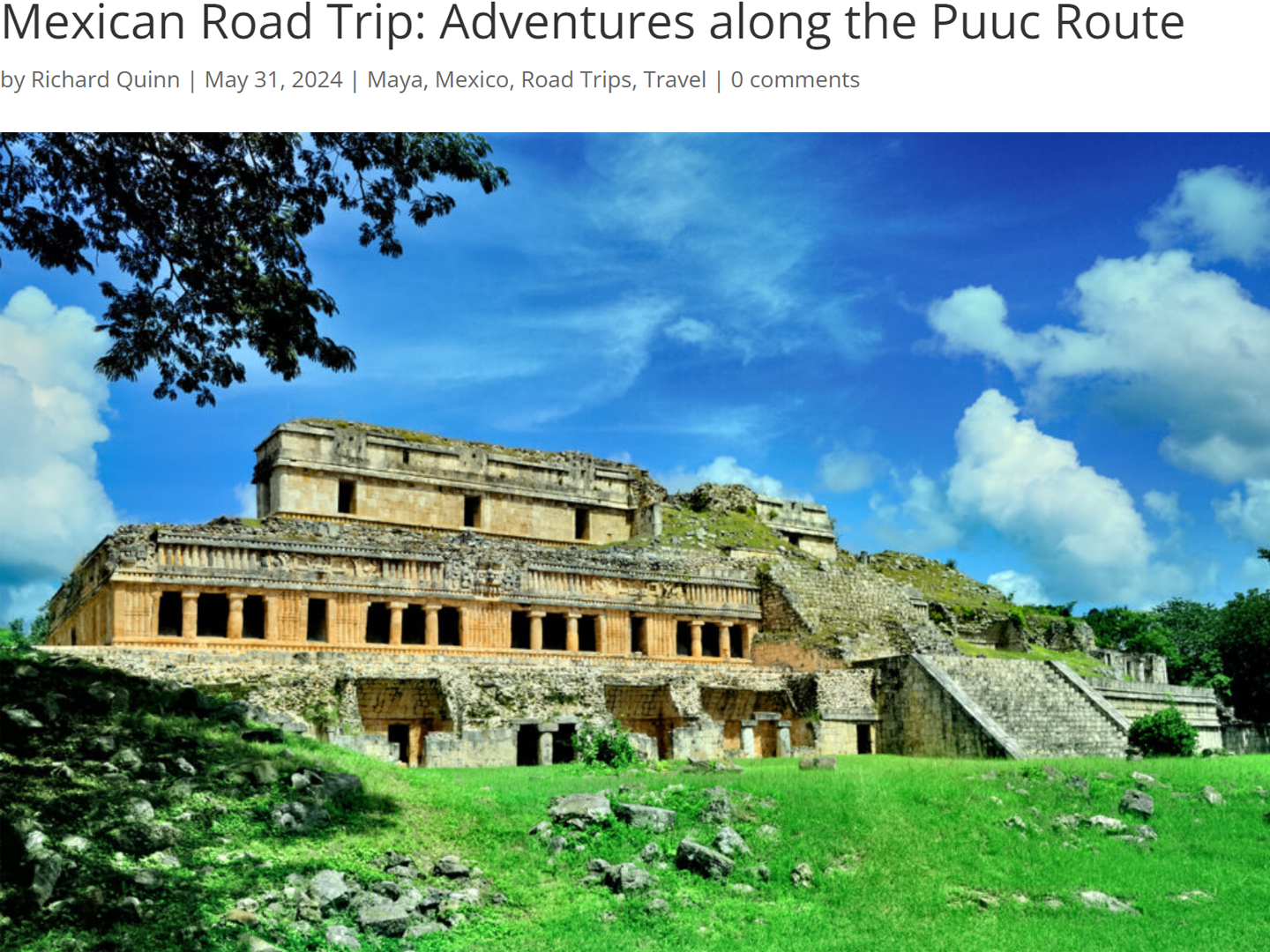

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

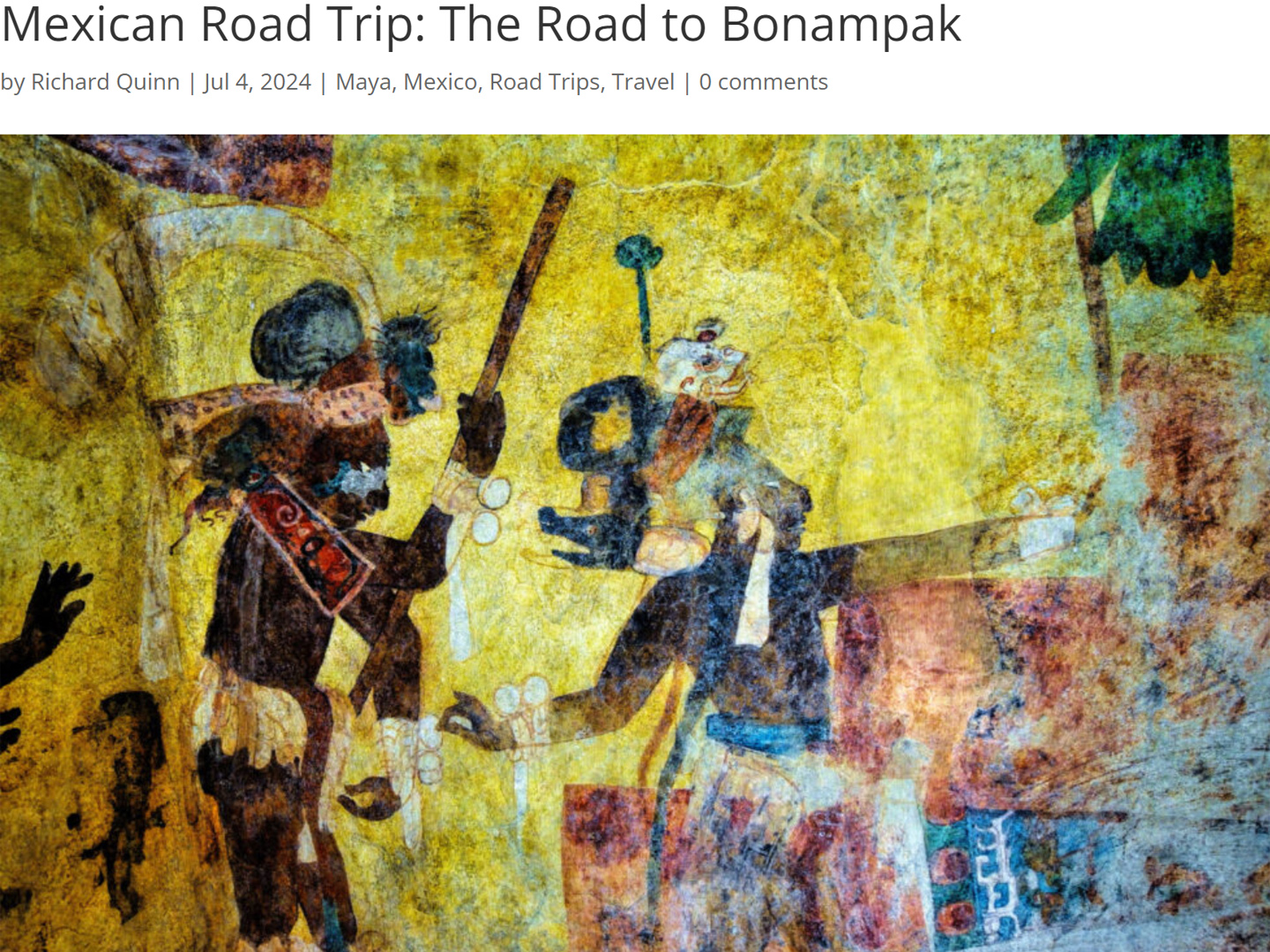

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we're left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it's 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

As we drove away from the toll plaza, a State Police car that had been parked off to one side made a fast U-Turn and started following me. A moment later, he turned on his flashers and gave me a short blast on his siren, motioning for me to pull over. Two uniformed policemen got out, and approached me on the driver's side. One of them hung back, apparently checking out my license plate before making a phone call.

"Documentos," said the officer by my window. "Licensia, los permisos, seguros, todo eso."

I wasn't sure if I was being stopped for some infraction, or if these guys were just fishing...

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in May, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in May, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico's Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they've adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It's a wonderful, colorful parade that's all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I've ever seen. There's a powerful energy in that spot--maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps--but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I've ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I've ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer's Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

This series of posts is dedicated to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. "Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins" was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after "Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali." We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Michael passed away in February of 2025, after 75 years of a life well-lived. He was unique, and he'll be missed.

Michael Fritz ("Elmo") 1949-2025

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments