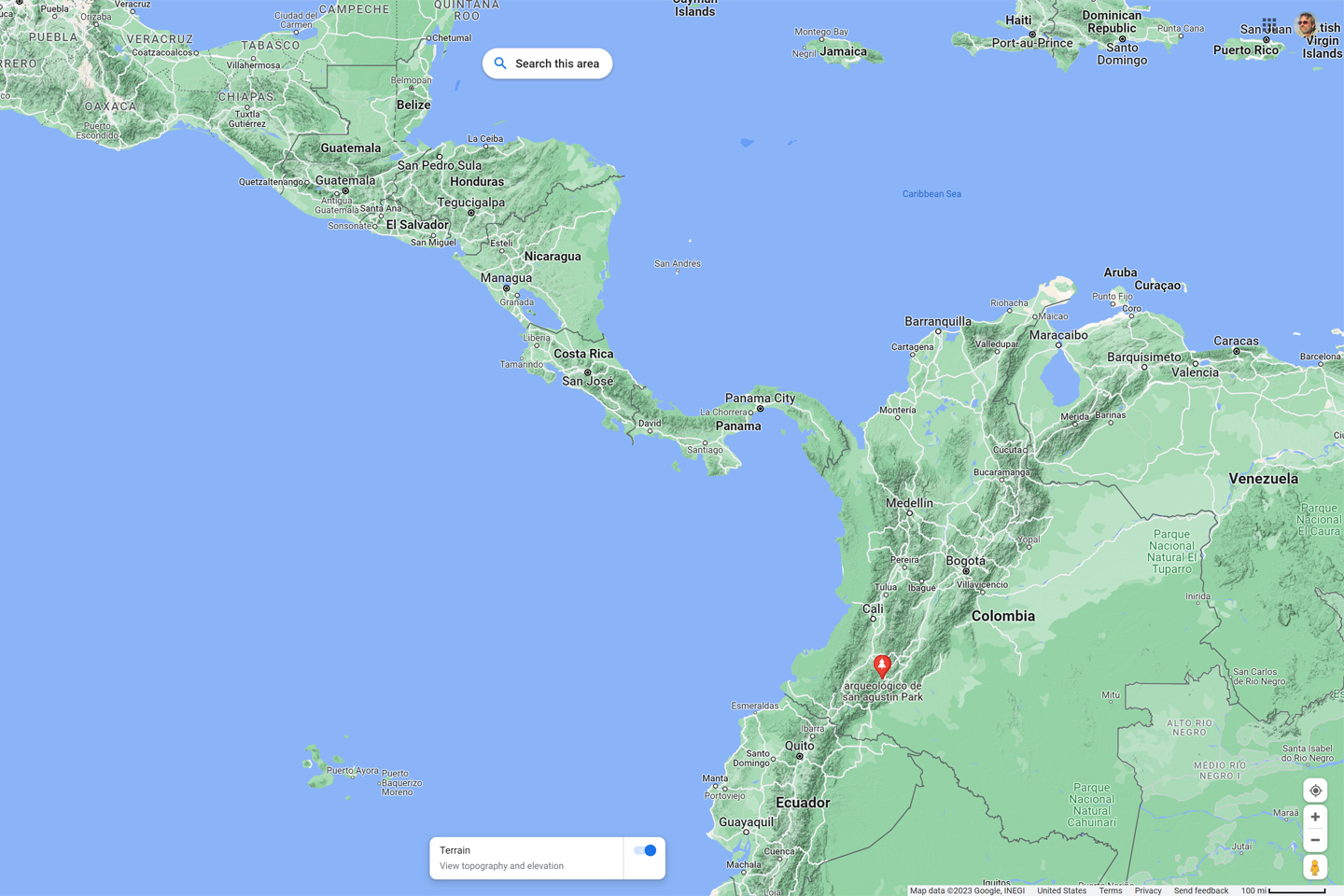

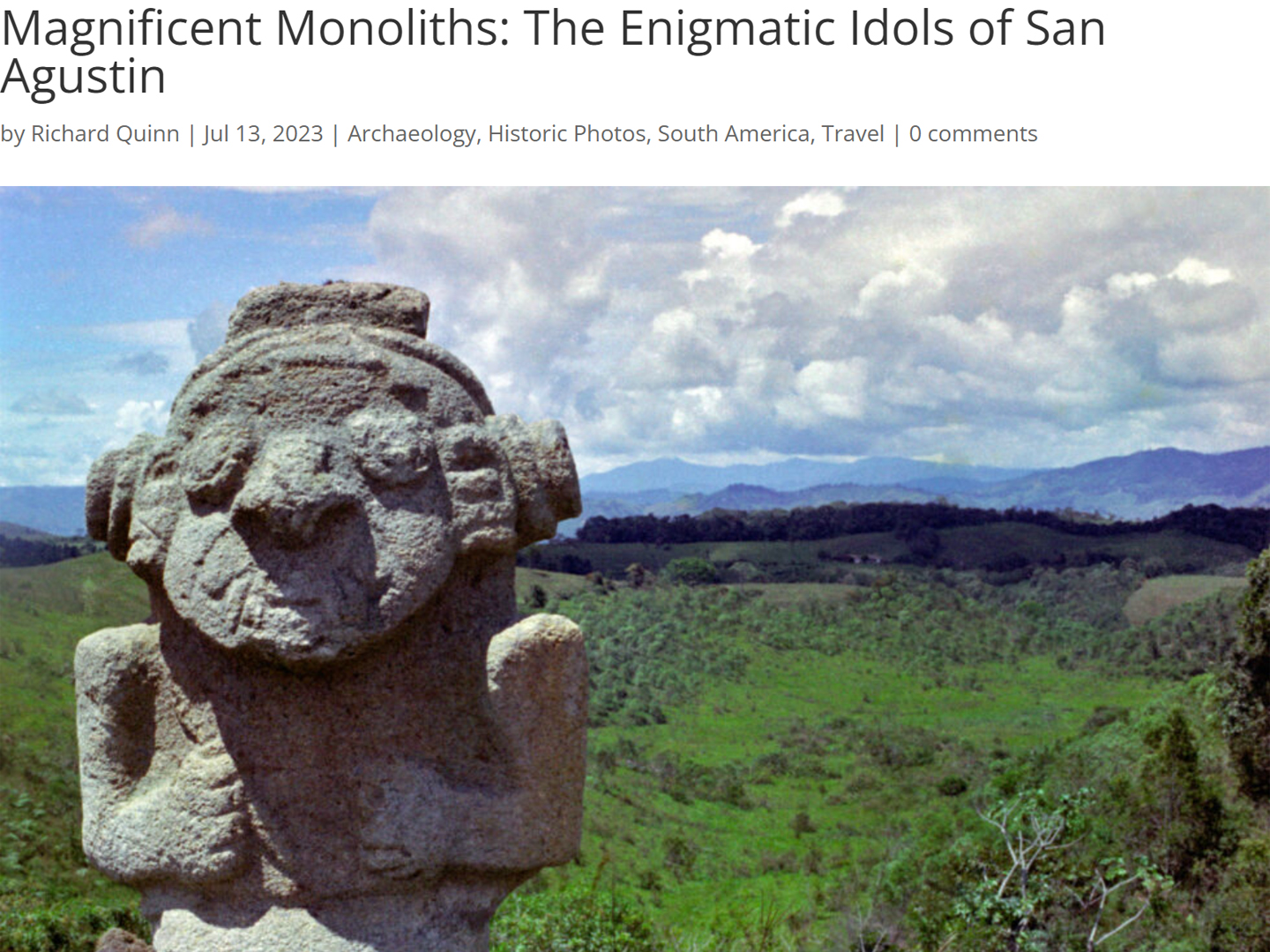

The San Agustin Archaeological Park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Huila Department of Southwestern Colombia, a mountainous region near the headwaters of the Magdalena River. Within the park is the largest complex of funerary monuments and statuary on the South American continent, hundreds of monolithic statues, carved from blocks of volcanic rock, standing as much as twelve feet tall. The complex includes dozens of burial mounds, hundreds of standing stones, and an assortment of elaborate mausoleums built with massive stone slabs. The statues represent gods and mythical beings, and were erected to adorn and protect the tombs of elite members of a society that flourished in these fertile intermontane valleys for more than two thousand years, beginning ten centuries before the time of Christ.

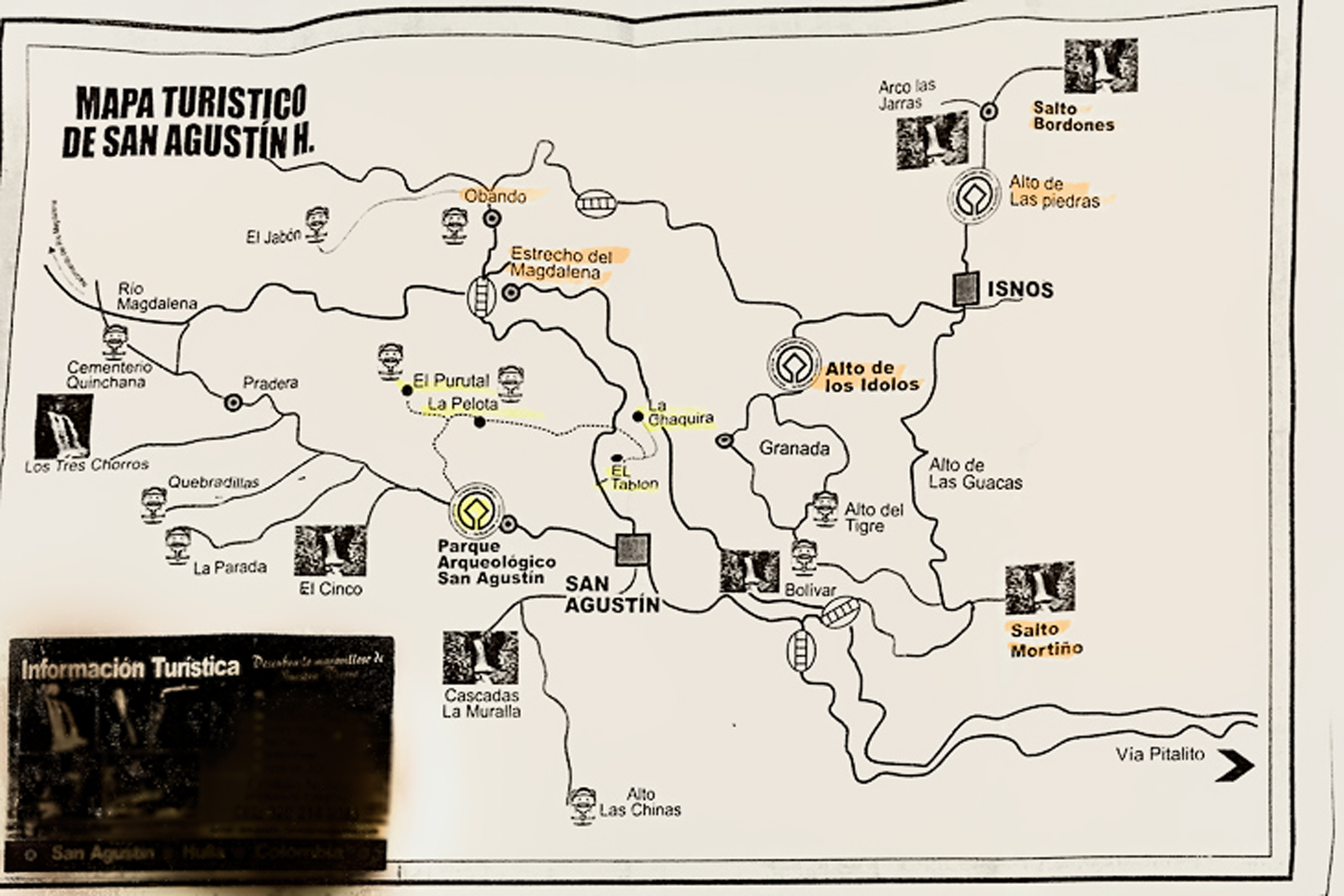

Location of the San Agustine Archaeological Park

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS FOR EXPANDED VIEW

Most of the statues and other durable monuments were erected during the Middle Period of this little-known culture, from about 425 AD until 1180 AD. The population went into decline after that, until the site was abandoned, around 1350 AD, and the necropolis was largely overgrown by the surrounding rain forest.

When Spanish troops arrived in the region in the mid-16th century, there was no organized resistance, so the colonists quickly took control, removing the original inhabitants from the most desireable plots of land, and setting up encomiendas, vast plantations worked by conscripted native labor. When the area near the ancient cemetery of San Agustin was acquired and settled, some time during the mid 18th century, the monuments were rediscovered, creating a minor furor. At that time, there was little interest in the cultural significance of such a find; what got people going was the potential for treasure! Ancient native burials were known to be loaded with valuable artifacts, so the grave-robbing treasure hunters, who were local people, for the most part, tore the place to pieces in their mostly unsuccessful search for gold. Many of the standing stones were toppled from their original positions by the looters, but the damage to the site was actually minimal. The only really valuable artifacts at San Agustin were the statues themselves, and those were simply too large and heavy to carry away.

The Archaeological Park of San Agustin was established in the early 1930’s, to protect and preserve the site. Land surrounding the largest concentrations of funerary structures and statuary was appropriated, a total of just under 300 acres, in three separate locations. The idols have been restored to an upright position to create displays for park visitors, with concrete pedestals added here and there to insure stability of the massive, multi-ton carvings. The arrangement of the standing stones and other funerary architecture conforms as closely as possible to the original placement, so this is a fascinating glimpse into the practices and beliefs of this complex ancient culture.

In 1993, San Agustin became a Colombian National Monument and Archaeological Park, and in 1995, it became a UNESCO site, designations that brought in much-needed funding for improvements to the infrastructure, while raising the park’s visibility, especially among international travelers. Even at that, the park is just just a bit too far out of the way for the average tourist, so you’ll never see excessively large crowds.

Parque Arqueologico San Agustin: the Early Days

Yesterday and today: San Agustin Statues in 1971, and more recently

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS FOR AN EXPANDED VIEW

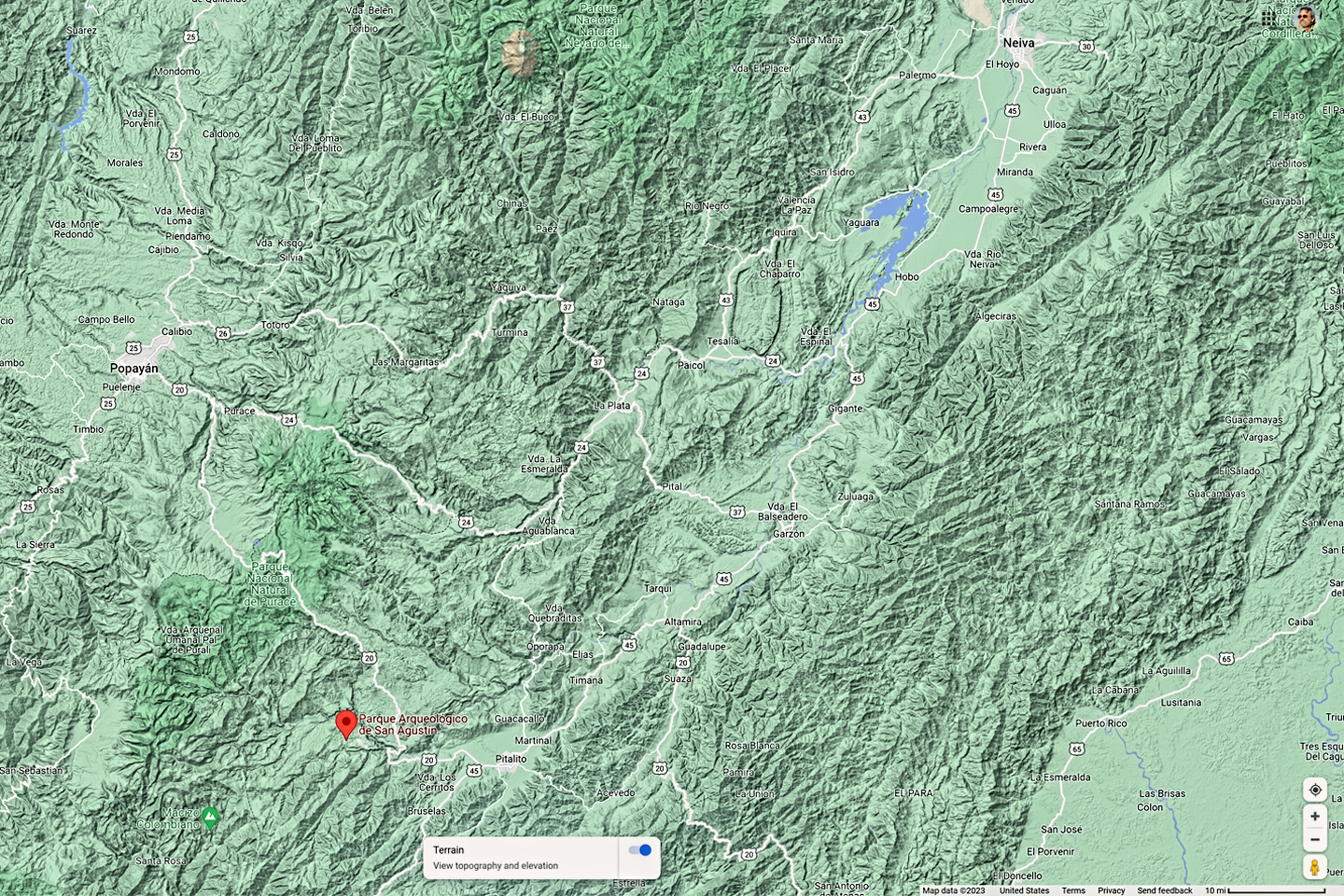

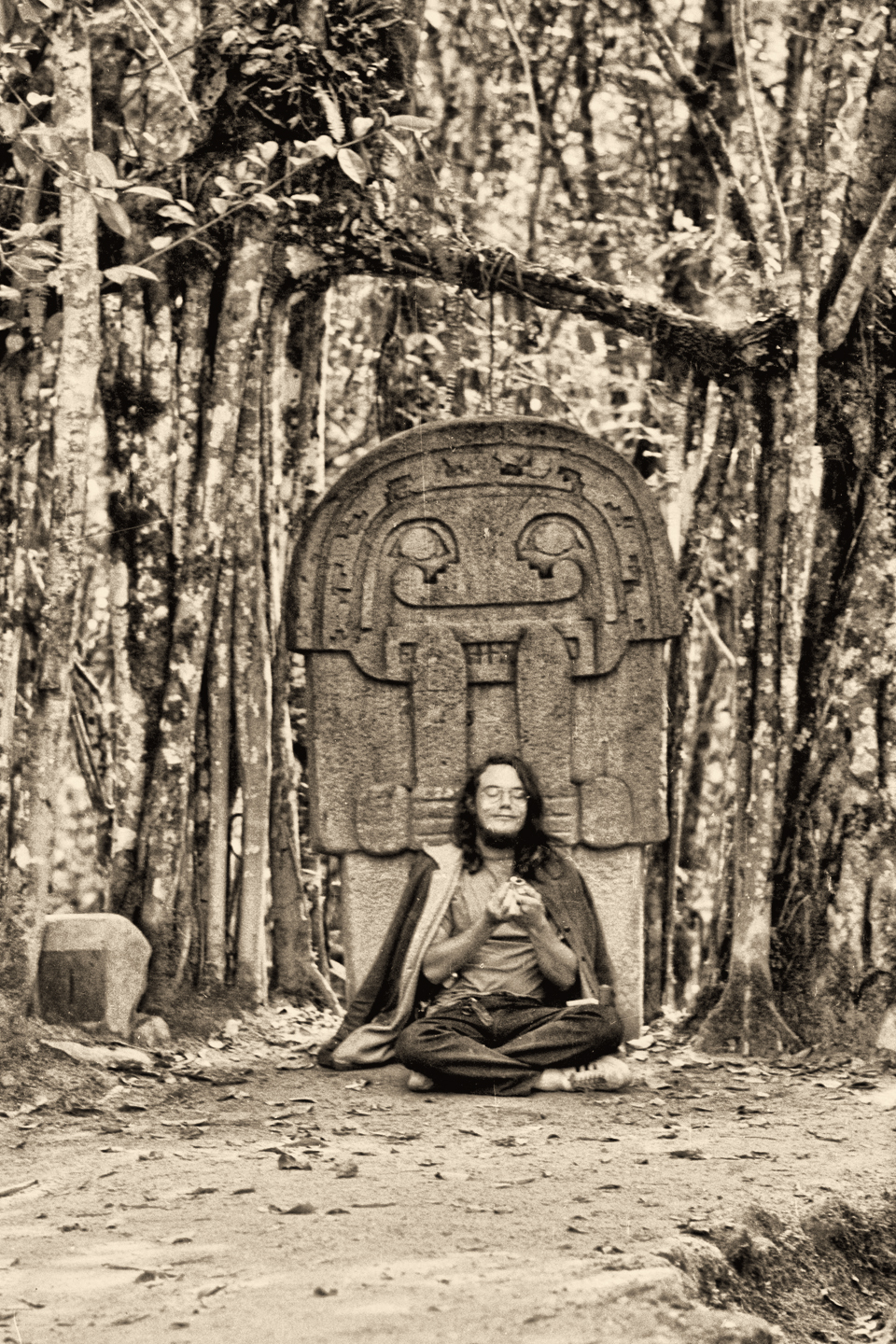

I visited San Agustin twice, once in 1971, and again in 1973, both visits far enough in the past to qualify as ancient history. Most photographs in this post are unique, in light of the many changes that have taken place at the park in the intervening half century. In those early days, the statues were left where they were found and minimally propped up. Burial mounds rippled across the landscape like rolling hills, where visitors were allowed to wander at will. You were welcome to touch, as long as you didn’t attempt to physically climb on the exhibits. Today, the displays are more solidly constructed, and there are fences around the monuments that prevent visitors from getting too close.

In 1971, the Archaeological Park was organized in much the same way as it is today. There are three interconnected sites that are close to the village of San Agustin: Las Mesitas (the Little Tables), Bosque de Las Estatuas (Forest of the Statues), and Fuente de Lavapatas (loosely, “Footwash Fountain”).

There are two additional major sites some distance away by road, on the other side of the Magdalena River: the Alto de Los Idolos (Mount of the Idols), and Alto de Las Piedras, (Mount of the Stones). The Park entrance fee provides access to all five of these locations, but not to any of the lesser sites scattered about the area on private land; admission to those, when required, is paid seperately.

Las Mesitas

San Agustin, the town, was much smaller in 1971, as you can see in my old photograph. In the main section of the park, adjacent to the town, there are three Mesitas, little tables, flat spaces where numerous tombs and burial mounds were concentrated. Some of the largest and finest tombs and statues in the park are located here, set up among the burial mounds, forming an impressive tableau of giant heads, warriors, and various deities. A bird with a snake in its mouth is a distinctly mesoamerican motif; one of many mysteries.

The village of San Agustin, along with several views of the monuments as they appeared in 1971, when there were no fences to obstruct the view.

Bosque de las Estatuas

The Forest of the Statues: This section of the archaeological park is a fanciful construct. They’ve taken several dozen statues recovered from various locations throughout the zone, and they’ve set them up along a path that meanders through heavy jungle growth. Temperatures are generally mild in San Agustin, but it can get warm and humid in the Bosque, so if you go, be sure to bring plenty of water. Even though they were not originally grouped together, the statues in the Bosque are a fascinating collection, displaying a wide diversity of artistic styles.

Lavapatas

The third site in the main area of the park is a short walk from the other two. The Fuente de Lavapatas is a section of rock-lined river bed that has been carved to direct the flowing water through a series of shaped channels into small pools; it’s a beautiful spot, with several natural waterfalls. Water management was important to this culture, so there’s no doubt that significant rituals took place here. Foot washing? Another bit of fanciful conjecture, but that’s probably as good a theory as any!

Two views of the Fuente de Lavapatas, the “Footwash Fountain.”

San Agustin Archaeological Park

CLICK MAPS AND PHOTOS FOR AN EXPANDED VIEW

Today, the entire region has been given a modern upgrade. It’s much easier to go there now: you can fly all the way to nearby Pitalito, instead of riding a bus for ten hours, and there are lodging and dining options ranging from rustic to upscale. The hotels arrange the tours: Half day or full day, hiking, horseback riding, and Jeep tours. Most visitors do a combination of these, and if you have access to a vehicle, you can easily visit the main sections of the archaeological park entirely on your own. A ticket, which costs about $8, grants entry to all park locations, and it’s good for two days. (Children under age 12, and adults over age 60 are admitted free.) The scenery alone is worth the price; the statues are a bonus!

Rio Magdalena

The Rio Magdalena is the Mississippi River of Colombia, a major corridor for transportation and commerce that flows most of the length of the country, from the heart of the Andean Cordilleras, all the way to Barranquilla, on the shores of the Caribbean. Before the advent of modern aviation, the only way to travel to Bogotá, the Colombian Capital was by riverboat, up the Magadalena to the foothills, and from there by mule train to the sabana, the high plain, at 8600 feet.

The Magdalena that runs near San Agustin is a far smaller river, but in a spectacular setting, flowing through a deep, steep-sided gorge, surrounded by kelly-green mountains. To visit the other two principle sections of the archaeological park, you have to cross to the other side of the river. This is easily accomplished, simply by taking Colombia Route 20, the road to the village of Isnos, which crosses the river on a sturdy highway bridge a few miles downstream from the gorge. There are buses, taxis, and frequent shuttles. If you have your own vehicle, it’s a piece of cake.

There’s an alternative that’s shorter in terms of distance, but longer in terms of time, and supercharged in terms of scenery. Some of the Horseback Tours follow a trail that descends the Magdalena Gorge all the way to the bottom, crosses the river on a bridge built for horses, takes in a beautiful waterfall, and goes up the other side to the Alto de Los Idolos. Sounds good, no? Horseback Tours are a popular activity in San Agustin, second only to the Jeep Tours, but it’s wise to be cautious: not all Horseback Tours are created equal, so you’d best know exactly what you’re getting into.

When I visited San Agustin for the second time, in 1973, I was traveling with my sister and two of her friends. We decided to try the horseback trek, and because there were four of us, they gave us a group rate on the horses, our own personal guide, and a choice of which route to take. The “easy” trips stayed south of the river and visited some of the sites on private land. The “tougher, but most beautiful” trip was the route that crossed the gorge. Not knowing any better, we let them talk us into the latter, and that turned out to be a mistake. None of us were what you’d call horse people, so the steep trail down to the bridge was daunting, and more than a little uncomfortable. The horses seemed to know what to do, and that was a good thing, because our “personal guide” was a young kid who was clearly inexperienced. While riding up the steep trail on the other side, our horses following one another in single file, my sister’s saddle came loose, and it didn’t simply slip. While the rest of us watched in horror, sister and saddle both slid completely off the back end of her horse and hit the ground, hard, no more than two feet from the edge of the cliff. She was stunned, and shaken, but she was able to stand up and walk away, and that’s the important thing. I won’t say she wasn’t hurt. She was damned sore for the rest of the week, and she had back trouble later in life that may well have originated with that incident, but needless to say, it could have been so much worse.

Magdalena River Gorge, Bridge, and Waterfall

Horseback riding on steep trails is an inherently dangerous activity. We accepted the risks when we hired the horses, but we chose poorly when we elected to attempt the route across the gorge, on the assumption that our young guide and his managers knew what they were doing, that the animals, as well as the tack and the saddles were in good condition and properly rigged. That’s what we get for assuming, and that’s the lesson that I’m passing along here: in North America, and in the other more developed countries, businesses offering tours to the public have to be licensed. They have to meet applicable safety standards, and are subject to inspection to insure compliance. We take that sort of thing for granted, but in a place like San Agustin, those rules don’t necessarily apply, and even when they do, they aren’t necessarily enforced. That means that the risks are greater at the outset, so when something looks or feels overly dangerous (like that trail to the bottom of the Magdalena Gorge), you might want to think twice about it.

Alto de los Idolos

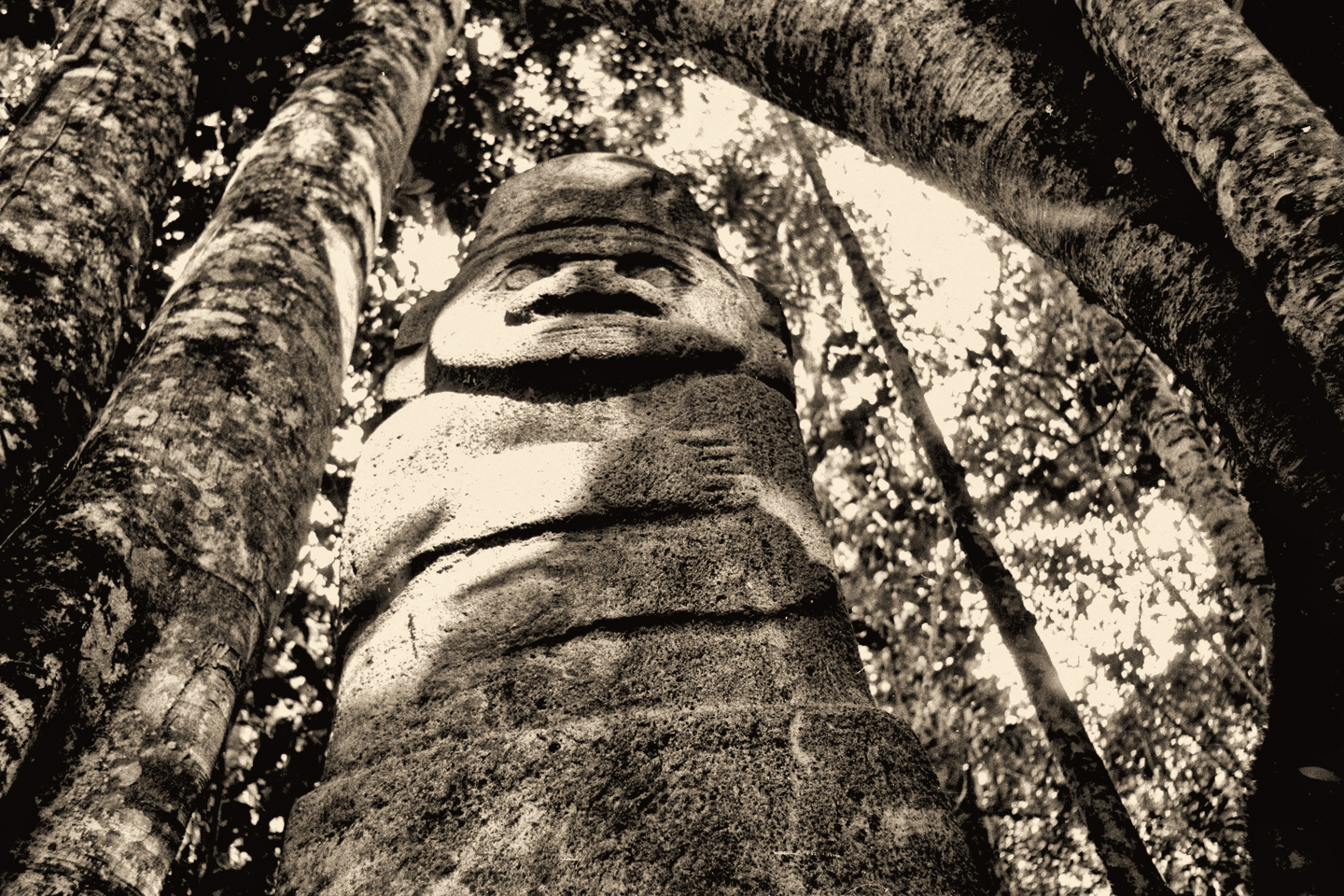

The Alto de Los Idolos is another large concentration of burial mounds, tombs, and megalithic statues. Standing stones and double-decker carved idols are lined up in rows, supporting large stone slabs that form a roof over the burial sites. Some of these are simple, while others are far more elaborate. There were tunnels and walkways both above and below ground, creating a village carved in stone, peopled by effigies of gods and demons.

One common depiction is that of a standing warrior wielding a club, with some smaller entity or creature seeming to ride on his shoulders. This smaller entity is thought to be an alter ego, or a guardian spirit. These warrior idols, thus protected, are usually placed in pairs at the front of the most important tombs.

The original necropolis was spread over a much larger area, but there’s enough here, and at the nearby sister site, the Alto de Las Piedras to give visitors a sense of what it must have looked like. (I don’t have any good photos of the Alto de las Piedras, so there isn’t a seperate section in this post.)

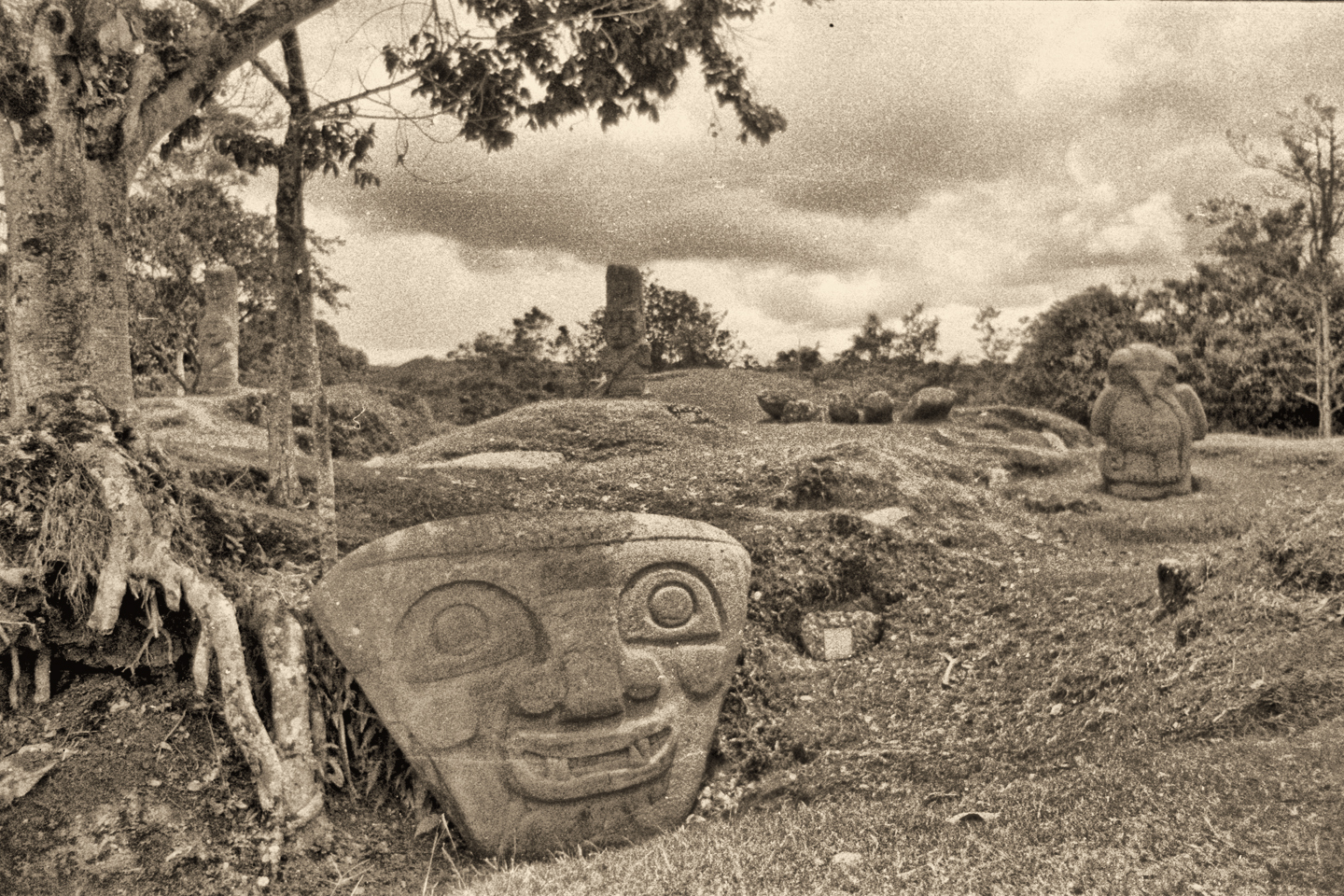

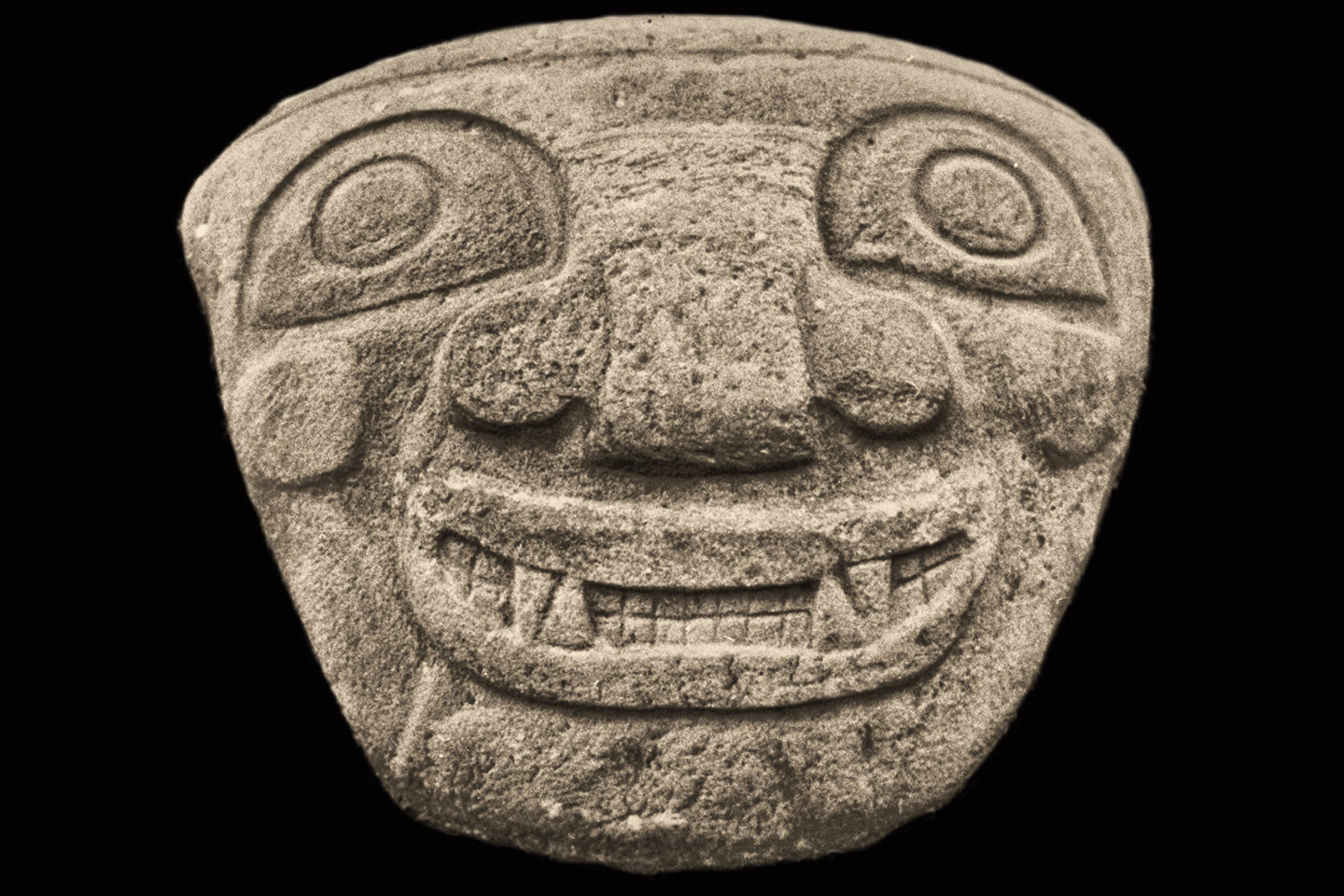

In a typical configuration, a pair of statues stand on either side of a carved idol. Most of them display the prominent fangs associated with the Mesoamerican jaguar cult, a common motif throughout the region. Large stone slabs stand on edge in parallel rows, supporting smaller slabs laid across the tops.

Another defining characteristic of the San Agustin culture are the stone sarcophagi, stone coffins with lids carved in the same style as the statues. Just as it was with the Egyptians, only the most important rulers got a burial that was this elaborate.

Size definitely matters. The biggest, most intricate statues grace the burials of the most important rulers. The San Agustin culture was really a group of Chiefdoms, some better organized and more prosperous than others. Small monument? Small chief.

This statue is one of the greatest mysteries of all. The first Sony Walkman didn’t go on sale until July of 1979, and yet here is a prototype version, carved in stone, no less, that predates the official release by at least 1,000 years. (I’m kidding, of course, but it makes you wonder!)

The Statues

The stone idols of San Agustin were created over the course of a very long span of time, almost 800 years, and while we like to think of the San Agustinians as a single, well defined pre-hispanic culture, there were actually a number of chiefdoms that were similar, yet with important distinctions.

At least 600 monolithic statues have been discovered in the Alto Magdalena region; 200 of them are preserved within the boundaries of the park, along with 20 monumental burial mounds, massive constructions as much as 30 meters across.

Each statue is unique, but taken as a group they provide a fascinating overview of the rituals and beliefs of one of the earliest complex societies in the Americas. The enigmatic idols of San Agustin are truly unmatched among the world’s ancient monuments.

The spectacular nature and the sheer quantity of monuments at San Agustin has made it one of the most studied of the many prehispanic cultures that developed in the northern Andes. There has been a fair bit of exploration and excavation, but the greatest emphasis has always been on the tombs and the megalithic carvings, which are hardly representative of the day to day lives of the people who created them. The relationships with other cultural groups, influences that helped shape their political organization, their religion and funerary practices, and their art, all of these remain open questions, because the painstaking stratigraphic research needed to document such connections is woefully lacking. Megalithic monuments are fascinating, drawing the attention of travelers and scientists alike, but it’s the pottery shards and the trash middens that yield the most information, and there is much work that remains to be done.

They say that more than half of ancient America still lies buried. The same goes for the truth behind the history. Until someone invents a functional time machine, there is much about what went on here that we’ll simply never know.

~~~~~~~~

The photographs in this post were all shot on 35mm film, which was scanned and extensively edited to clean up scratches and flaws in the emulsion, the result of half a century of incautious handling and less than ideal storage conditions. Some color correction was necessary, to counter the inevitable fading. The resulting digital images aren’t as sharp as I’d like them to be, but they’re near and dear to my heart: they’re historical photographs, and the history that they reflect is my own.

(Unless otherwise noted, all of the images in these posts are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

MORE SOUTH AMERICAN ADVENTURES:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

Long Ago and Far Away: South America in the Early 1970's

Portraits of a People, Lost in Time

50 year old portraits of Andean natives in their traditional dress, taken in mountain villages not yet tainted by outside influences.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Puno Day Festival

Historic photos of Peru's Puno Day festival, taken in 1971. Included is the reenactment of the birth of the Inca empire on the shore of Lake Titicaca, with costumed dancers lining the streets of Puno.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Chinchero: The Place Where Rainbows are Born

Candid portraits of villagers in traditional dress, taken in Chinchero, Peru in 1971, before the outside world intruded.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

An Overabundance of Bowlers: A Brief History of Headgear on the High Plateau

Andean natives have adapted to the intensity of the high altitude sun by taking a very simple precaution: everyone, almost without exception, wears a hat when they venture outdoors.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Magnificent Monoliths: The Enigmatic Idols of San Agustin

At least 200 monolithic statues are preserved within the boundaries of the San Agustin Archaeological Park, along with 20 monumental burial mounds. Each statue is unique, but taken as a group they provide a fascinating overview of the rituals and beliefs of one of the earliest complex societies in the Americas. The enigmatic idols of San Agustin are truly unmatched among the world’s ancient monuments.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments