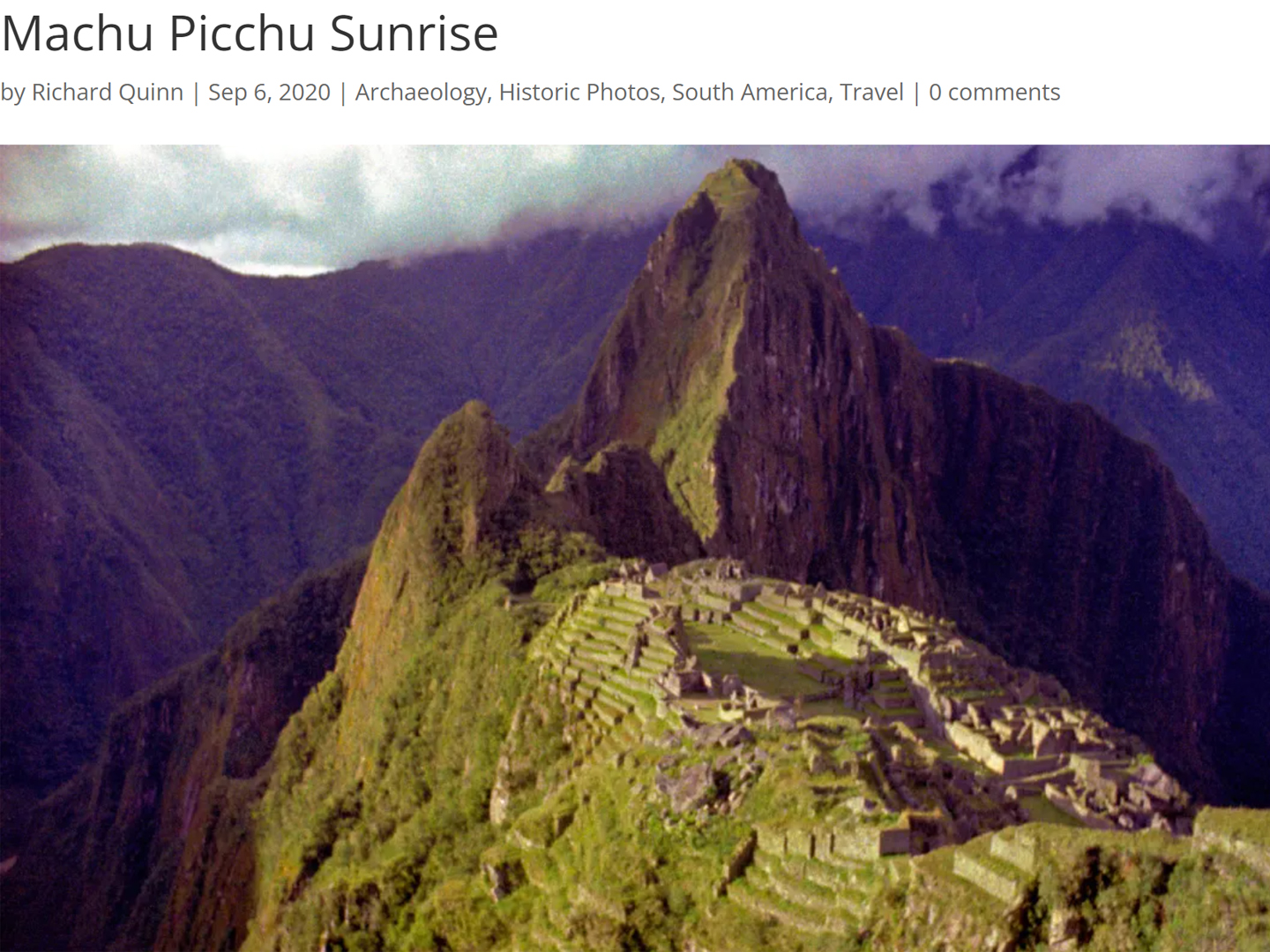

Machu Picchu, the Lost City of the Incas, is a 500 year old complex of ruins located deep in the Andes of south central Peru. In 1983, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and in 2007, it was voted as one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. In gaining that distinction, Machu Picchu joined an impressive assortment of locations that includes the Roman Colosseum, the Taj Mahal and the Great Wall of China, after besting everything else in the running, from the Giza Pyramids to Angkor Wat. The publicity surrounding the selection raised the world’s awareness of an attraction that was already wildly popular, and in the years that followed, the number of visitors swelled to as many as 6,500 people per day.

Before the Covid-19 Pandemic: To better accommodate the crowds, they divided the days into two time slots: 6 AM to Noon, and Noon to 5:30. Visitors had to choose one or the other, and they were advised to book their preferred date and time slot as many months in advance as possible.

While touring the ruins, all visitors had to be accompanied by a guide, and they had to follow pre-designated paths, at a predetermined pace calculated to keep all those people moving. It was hardly the ideal, especially for travelers who are accustomed to exploring ruins such as this on their own, but in the case of ultra-popular Machu Picchu, they simply didn’t give you a choice. This photograph (which is from the Internet, NOT one of mine) is typical of what all that looked like. The setting is still spectacular, unmatched in all the world, but there were people, people, and more people, everywhere you looked.

AFTER the Covid-19 Pandemic: There were travel restrictions put in place due to the pandemic that significantly altered the situation at Machu Picchu, reducing the maximum number of visitors allowed into the ruins each day. When the pandemic ended, the restrictions remained. Maximum daily visitors is now 5,600–which is still a lot, but the herd is broken into small groups and confined to “circuits,” routes within the ruins. If the pre-pandemic rules seemed restrictive, the new rules are on a whole different level. All movement is tightly controlled and strictly timed, in most cases to a maximum of 2 hours and 30 minutes (some of the hiking “circuits” give you most of the day). Reservations are required 40 days in advance. For a complete breakdown of the latest rules and regulations, visit the following link: New Rules for Machu Picchu Visit in 2025

Peruvian authorities are caught in the middle: tourism is vital to their economy, representing almost 10% of their GDP, so increasing the number of visitors is a logical goal–but in reality, it’s a quandary, because nearly every tourist who comes to Peru wants to see Machu Picchu. Too many people trooping through their star attraction increases the wear and tear on the ancient stairs and pathways, which are already in danger of permanent damage, and from the visitors perspective, too large a crowd takes a good bit of the thrill out of their “once-in-a-lifetime” experience. By limiting the number of tickets sold and rigidly controlling access to the site, they’ve created a sense of order, but they’ve yielded to the demand, and allowed the visitation numbers to increase beyond the maximum levels recommended by UNESCO. At this point, the super-sized crowds have simply become a part of the ambiance. There is only one Machu Picchu, after all, and if you want to see it for yourself, you have to do so from within the ambulatory confines of a herd of your fellow humans.

I won’t get into the specifics of how and where to buy your tickets, or the best season of the year for trekking, or the best timing of a tour for photo buffs. That information is widely available elsewhere, and any advice I might have for you based on my personal experience would be half a century out of date!

I’m not usually all that eager to admit to my age, but in this case, being an old guy makes me one of the lucky ones. I got to visit Machu Picchu—twice—long before all the hoopla that drew the big crowds, and I even got to sleep overnight in the ruins–but I’d best slow down, because I’m getting ahead of myself.

The following is a tale from my personal archives, dating back to February, 1971:

Machu Picchu Sunrise

Half a century ago, I was a 20 year old college student taking a break from my classes, hitch-hiking through South America on the cheap, and having the time of my life. I’d fallen in with a couple of guys who were friends from the University of Michigan, and they’d come to Peru with a specific intention: they wanted to visit a place called Machu Picchu, an Inca ruin that was somewhere in the mountains southeast of Lima. I’d never heard of Machu Picchu, but the way those guys described it, I figured it was something I probably needed to see.

The three of us took a passenger train due east into the massive, barren folds of the Peruvian Andes, climbing endless switchbacks through tunnels and over bridges, finally cresting a 16,000 foot pass before descending to a small city called Huancayo. We looked up some acquaintances of mine who were stationed there in the Peace Corps, and spent a couple of days with them, adjusting to the altitude and swapping travel stories. Everyone agreed that Machu Picchu was the ultimate destination, but in order to get there, we first had to get to Cuzco, the old Inca capital. At that time, the only way to travel from Huancayo to Cuzco was by bus. There was just one bus line, and just one bus per day—and it carried, in addition to passengers, cargo of every description, including pigs, chickens, and goats. Total distance was less than 500 miles, but the mountain roads were so horrendous, and the bus was so slow and overloaded, that it took 48 hours to complete the journey. The barely-cushioned seats were all assigned in Huancayo. If you were lucky enough to have one, you held on to it for dear life, because anyone getting on the bus from that point to the end of the line had to stand in the aisle, hang out of the doorway, or climb atop the luggage that was strapped to the roof. Doing the trip in stages would mean losing our seats, so we settled in, packed into that bus like so many stinking sardines, and we toughed it out. Those were possibly the longest 48 hours of my life, and among the most weirdly beautiful.

This photo was taken at a spot where we stopped for an hour or so, waiting for a road crew (6 Indians with bowler hats and shovels) to repair a washed out spot along a riverbank.

Arriving in Cuzco after that ordeal was an extraordinary experience—there was monumental Inca stonework everywhere, in some cases serving as the foundation for Spanish Colonial buildings and churches, a blatant attempt by the Conquistadores to smother the grandeur of the Inca’s capital city.

There was a special train from Cuzco to Machu Picchu that ran every day, hauling a load of tourists to the ruin every morning, and hauling them back every afternoon. We bought tickets and boarded, feeling strangely out of place, since most of the other passengers were foreigners who had flown all the way to Cuzco, bypassing the adventures and the deprivation and suffering that we, the true travelers had so recently endured. Perhaps it could be said that my companions and I were more appreciative of the experience, since we’d had to so seriously work for it, but in the final summation, none of that mattered, because there we all were: the bedraggled back-packers and the overweight German tourists and the Japanese with far too much camera gear, and the loud ladies from New York with their rude complaints; indeed, there we all were, riding on the same train, headed to Machu Picchu. The train stopped at a station in what seemed the middle of nowhere, in a deep canyon surrounded by lofty green peaks, a few thousand feet lower than Cuzco, and far from the desert coast, so far more tropical. The passengers spilled out, and a fleet of little vans ferried everyone to the top of the ridge.

Arriving at Machu Picchu is like your first live glimpse of the Grand Canyon. You come over a rise, or around a corner, and there it is, looking like all the pictures you’ve ever seen of it, only more so—because there’s no picture anyone could ever take that would really do it justice. It’s more like a vision than a real place, a soaring statement in tribute to an ideal that’s been lost in the mists of time. Just standing there and taking it in, that was a moment I’ll never forget, and it moved me profoundly.

We toured the ruins, checking out all the angles, but it was almost impossible to get the perfect photos I wanted, because there were people everywhere, two hundred or more that had arrived on the train with us, and they were climbing all over everything, sticking out like sore thumbs in their brightly colored shirts and straw hats, ruining the ambience. (Compared to today, that was nothing, barely a whisper, but back then, we were all pretty spoiled!) After four, maybe five hours, the herd migrated back toward the concession area, lining up to catch the vans back down to the train station for the return trip to Cuzco. There was one hotel at the site—but it only had a dozen rooms, booked as much as a year in advance and crazy expensive, so 90% of the crowd left with the train. My friends and I stayed, as did the handful of hotel guests, and a couple of French backpackers.

We planned on finding an out-of-the-way spot to roll out our sleeping bags, but the options were limited. Camping anywhere near the ruins was strictly prohibited, and hippies with backpacks weren’t welcome anywhere near the hotel. The sun started going down, we still had no idea where we were going to sleep—and then it started to rain. Softly at first, but then it poured! There was a main gate on the trail to the ruins, locked up tight for the night, and there was a small shelter for the gatekeeper who was there to insure that no one tried to slip through after hours. We made a beeline for the shelter, and the gatekeeper took pity on us—me, my friends, and the French guys— and he invited us to share his space, in out of the wet. Someone produced a bottle of something, brandy maybe, and we passed it around, the gatekeeper taking perhaps a bit more than his share. Not long after draining the bottle, the poor old guy passed out, dead drunk. And then the rain stopped. We all looked at each other. Then we looked at the gate, and at the oblivious gatekeeper, and at the gate key hanging on a hook, and then back at the gate again. Without saying a word, we all stood, someone unlocked the gate, and we trooped silently into the ruins of Machu Picchu on that stormy, starless night. Several of the structures within the ruins had been re-roofed with thatch, so they actually made perfectly acceptable shelter, and we found a wonderful spot to stretch out and drink in the magic and the power emanating from that ancient city in the clouds.

At first light, the whole place was enshrouded in fog:

It was beyond amazing. I was practically hyperventilating I was so excited, spinning around, leaping along the terraces, trying to make every shot count, because I only had just a few rolls of film. I finished the black and white I’d been shooting, and threw in a roll of Ektacolor (color negative film). I shot the foggy terraces again, this time in color:

Then the sun came out:

I ran up those stairs, to a better vantage point, where I could see the whole thing spread out below me, and spotted a herd of alpacas, grazing like they owned the place:

A light rain in the distance, with the sun behind it, created an unforgettable photo opportunity:

The five of us had Machu Picchu entirely to ourselves for at least twelve hours. It was like a dream, and a very fine dream, at that. I’m sure there are other travelers from my generation (or prior) who had similar opportunities, particularly anyone who was there at Machu Picchu before the backpackers arrived in force, but from what we were told at the time, we were among the last who would ever get away with doing what we did. Security got much tighter from that point forward, and by the time of my second visit to Machu Picchu two years later, the kindly gatekeeper had been replaced by a squad of Peruvian soldiers armed with automatic weapons–but, once again, I’m getting ahead of myself. That will be a story for another time.

They go to a lot of trouble to clear everyone out at closing time, and to keep everyone out until the following morning. If anyone did manage to sneak around the locked gates or climb up to the ruins from below, chances are, they would be caught pretty quickly, and they would be in serious trouble, in violation of a long list of statutes and regulations. They would be facing hefty fines at minimum, and possibly even jail time. Would it be worth it? Probably not, but I will say this: the morning at Machu Picchu that I’ve just described is one of my most cherished memories, and yet, according to the rules in place at the time, I wasn’t supposed to be there. I don’t advocate rule breaking, or trespassing, or the presumption of any special privileges when it comes to touring Machu Picchu, or any other historical attraction, but you have to put these things in context. There are times, in the course of a life well-lived, when you might have to blur the lines a little, and trust your instincts. Cherished memories beat the heck out of regrets!

~~~~~~~~

The photographs in this post were all shot on 35mm film, which was scanned and extensively edited to clean up scratches and flaws in the emulsion, the result of half a century of incautious handling and less than ideal storage conditions. Some color correction was necessary, to counter the inevitable fading. The resulting digital images aren’t as sharp as I’d like them to be, but they’re near and dear to my heart: they’re historical photographs, and the history that they reflect is my own. Several of the pictures were taken with Ektachrome Infrared color slide film, shot through a set of colored filters. Why? Hey, why not!

Click any of the images to blow them up to full screen, with captions. There are forty photos, and just one of them has a single tourist visible. See if you can find him!

(Unless otherwise noted, all of the images on this site are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

Long Ago and Far Away: South America in the Early 1970's

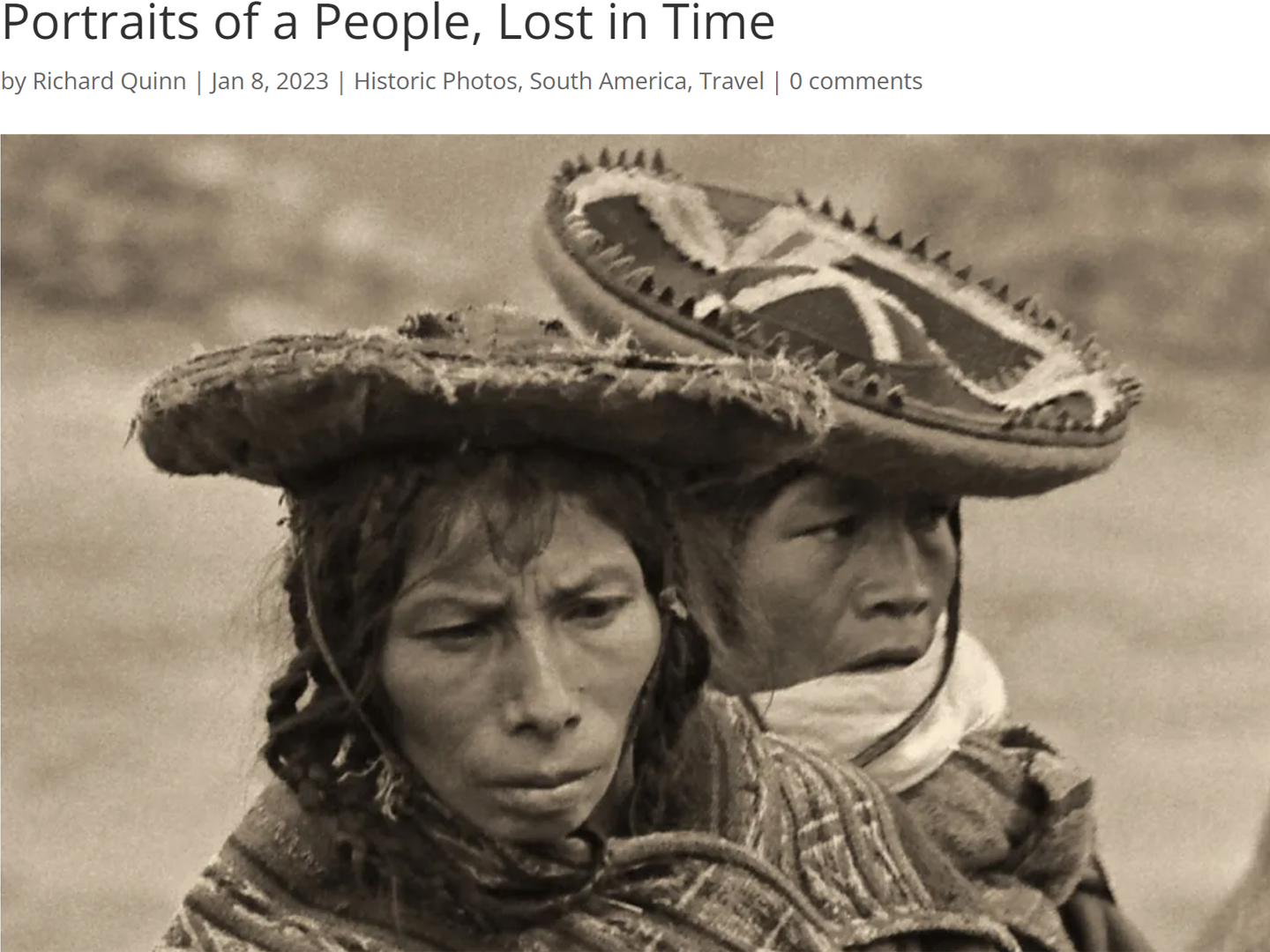

Portraits of a People, Lost in Time

50 year old portraits of Andean natives in their traditional dress, taken in mountain villages not yet tainted by outside influences.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

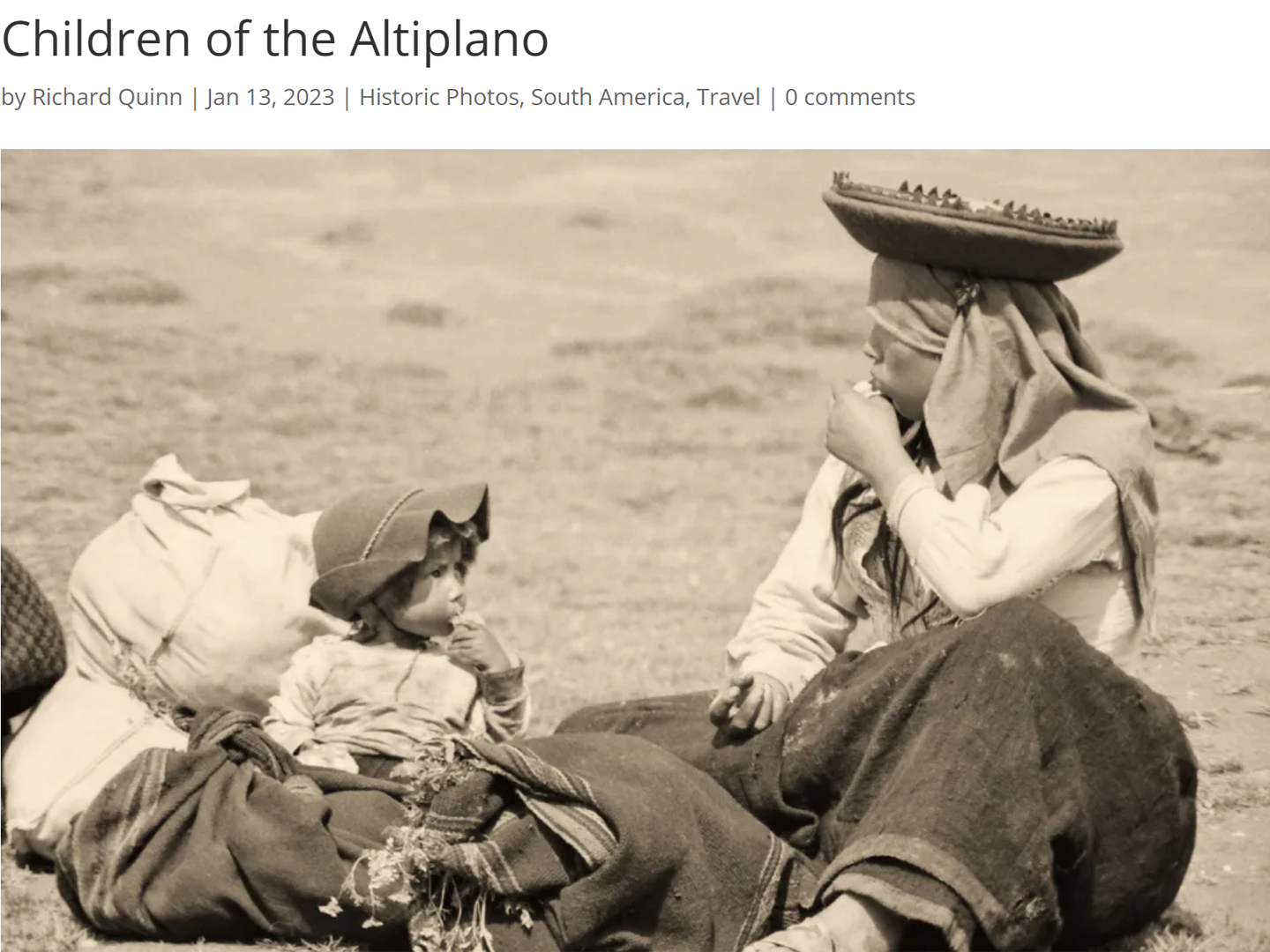

Puno Day Festival

Historic photos of Peru's Puno Day festival, taken in 1971. Included is the reenactment of the birth of the Inca empire on the shore of Lake Titicaca, with costumed dancers lining the streets of Puno.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Chinchero: The Place Where Rainbows are Born

Candid portraits of villagers in traditional dress, taken in Chinchero, Peru in 1971, before the outside world intruded.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

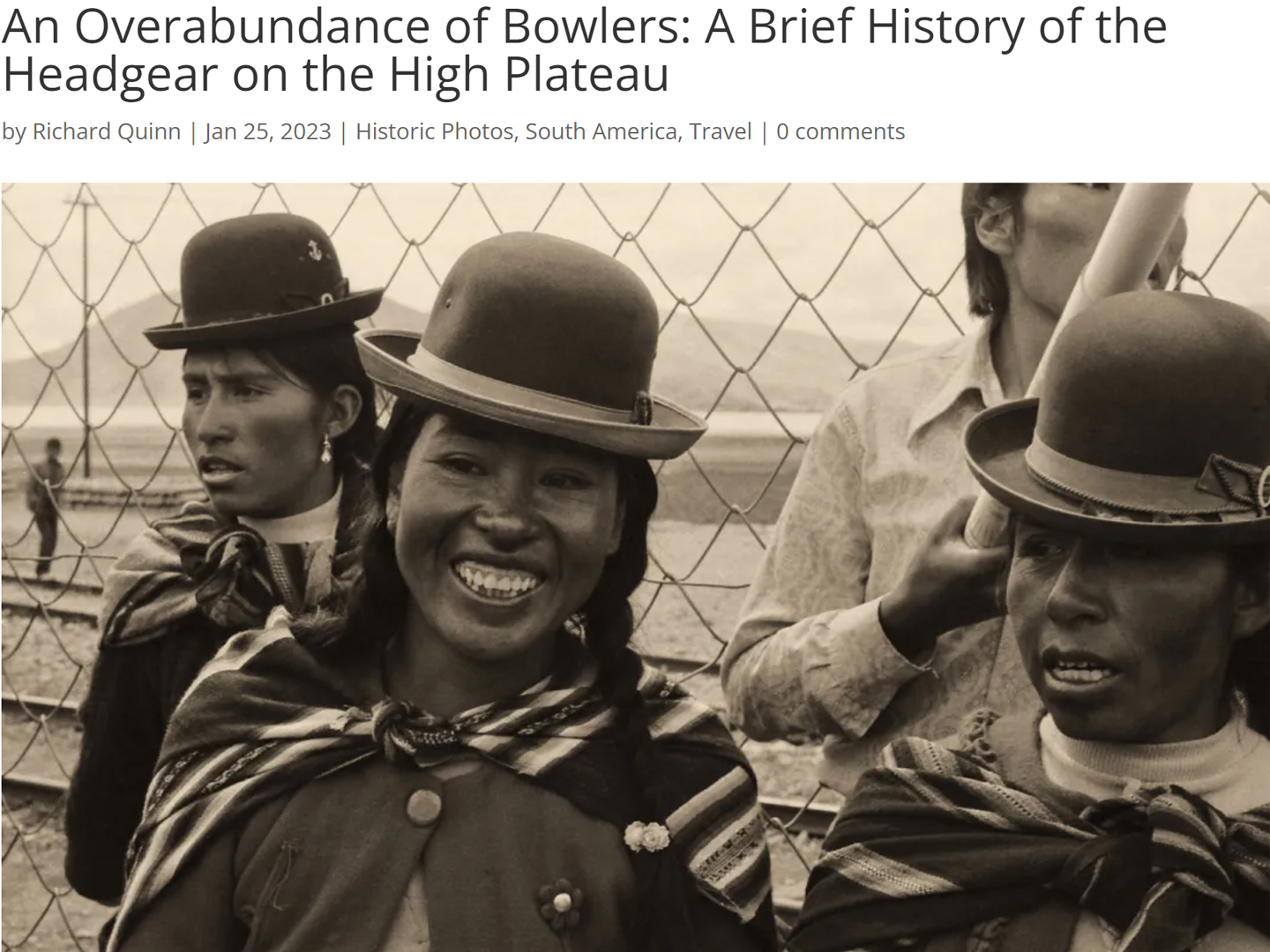

An Overabundance of Bowlers: A Brief History of Headgear on the High Plateau

Andean natives have adapted to the intensity of the high altitude sun by taking a very simple precaution: everyone, almost without exception, wears a hat when they venture outdoors.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

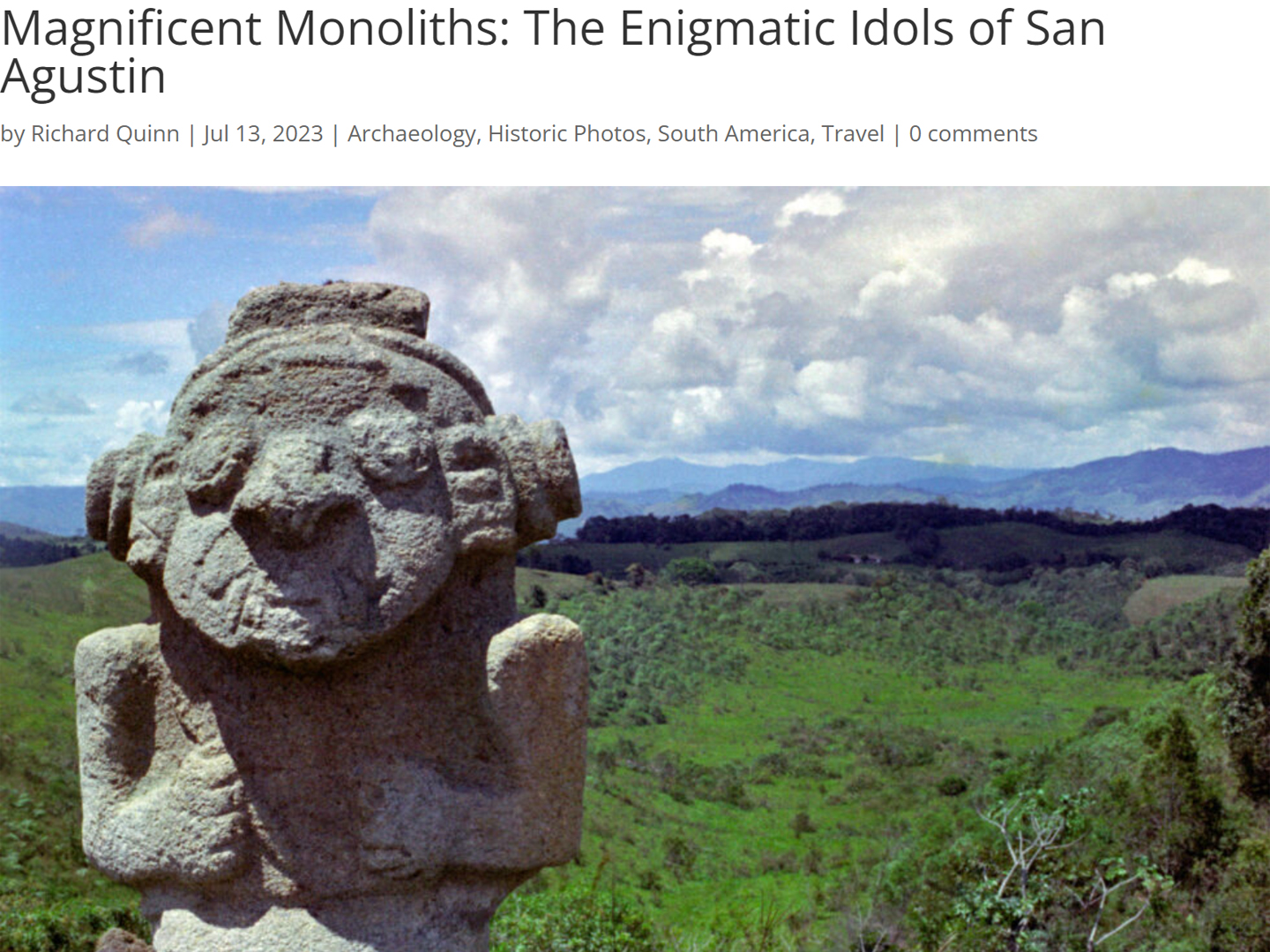

Magnificent Monoliths: The Enigmatic Idols of San Agustin

At least 200 monolithic statues are preserved within the boundaries of the San Agustin Archaeological Park, along with 20 monumental burial mounds. Each statue is unique, but taken as a group they provide a fascinating overview of the rituals and beliefs of one of the earliest complex societies in the Americas. The enigmatic idols of San Agustin are truly unmatched among the world’s ancient monuments.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments