Edzná (Edz-nah, pronounced just like it’s spelled) is one of the best kept secrets in the Yucatan. The average tourist has never heard of this particular Mayan ruin, so you would think, based on its lack of notoriety, that there’s nothing special about it. In reality, Edzná is so far beyond special, it qualifies as epic, like classic lyrical poetry comprised, not of words, but of temples and palaces carved in stone that have stood, in regal grandeur, for more than a thousand years. In the Mayan language Edzná means “House of the Itzás”. And yes, those would be the same Itzás who went on to found the more famous Mayan metropolis known as Chichen Itzá, the most powerful city in the history of the northern Yucatan. Those Itzás were a big deal in the Yucatan of their day, and Edzná is where they got their start.

The location of Edzná, relative to Chichen Itzá and Cancun.

Click for an expanded view of all maps and photos

HISTORY OF EDZNÁ

Edzná was first settled about 600 BC, but it took close to 800 years before it really came into its own. By 200 AD, the city was flourishing, ultimately becoming home to some 25,000 people, spread across an area of 25 square kilometers, or nearly ten square miles. This was a center of significant influence in the Late Classic era of Mayan civilization, from 400 AD to 1000 AD. There was a regional collapse of the Mayan social structure in the 10th Century, and the cultural phase we call Post Classic rose from the ashes. At about that time, a group that became known as the Itzás moved into the Yucatan from the Peten region of Guatemala. They took conrol of Edzná, and ran the show there for nearly 500 years.

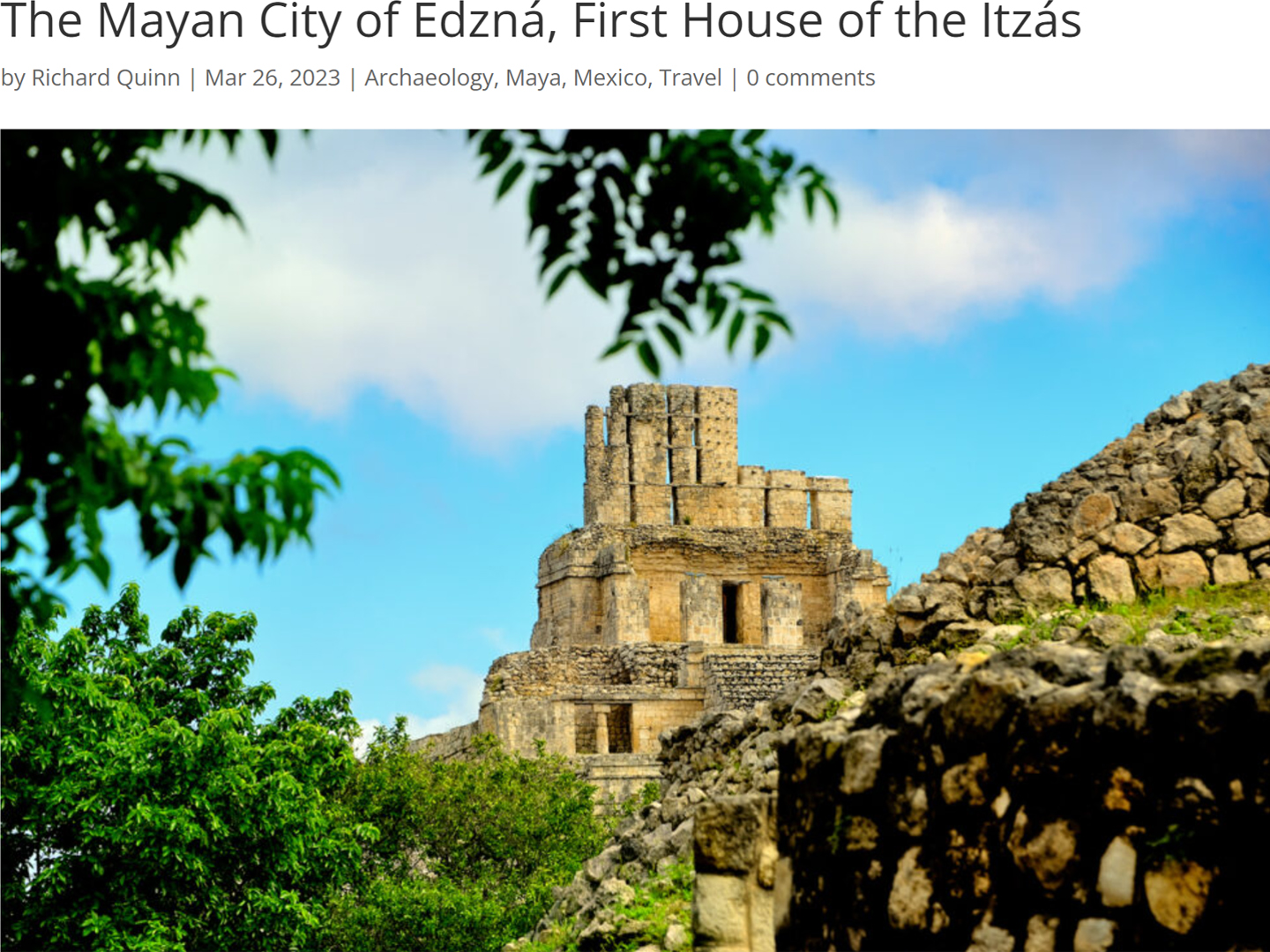

Castle of the Five Floors, rising above the tree tops, just as it has for more than a thousand years

The Itzás were smart enough to ally themselves politically with the powerful Lords of Calakmul, the rulers of the lands to the south and east. That alliance helped keep them safe–and it helped keep them in power.

THE MYSTERY OF THE ACROPOLIS

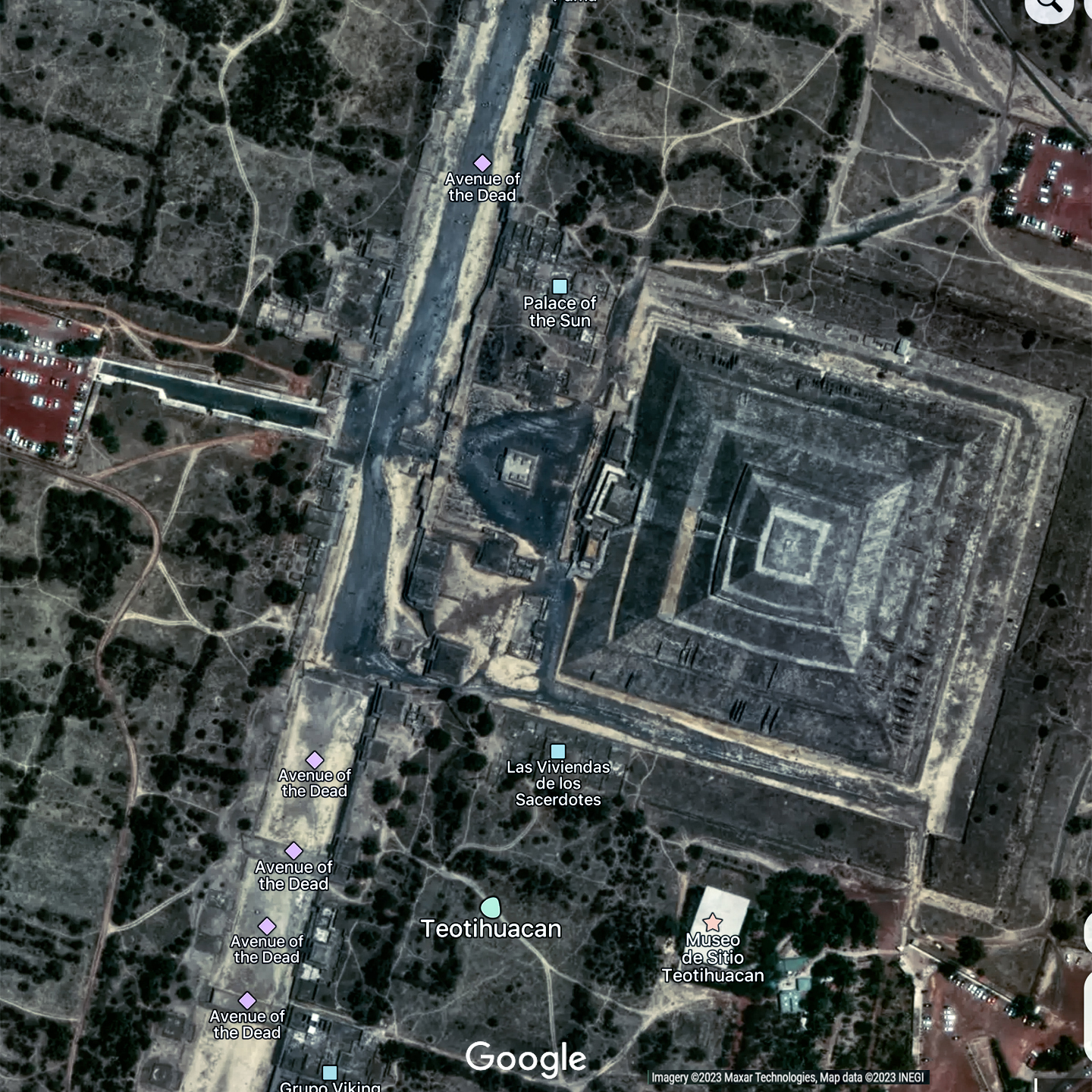

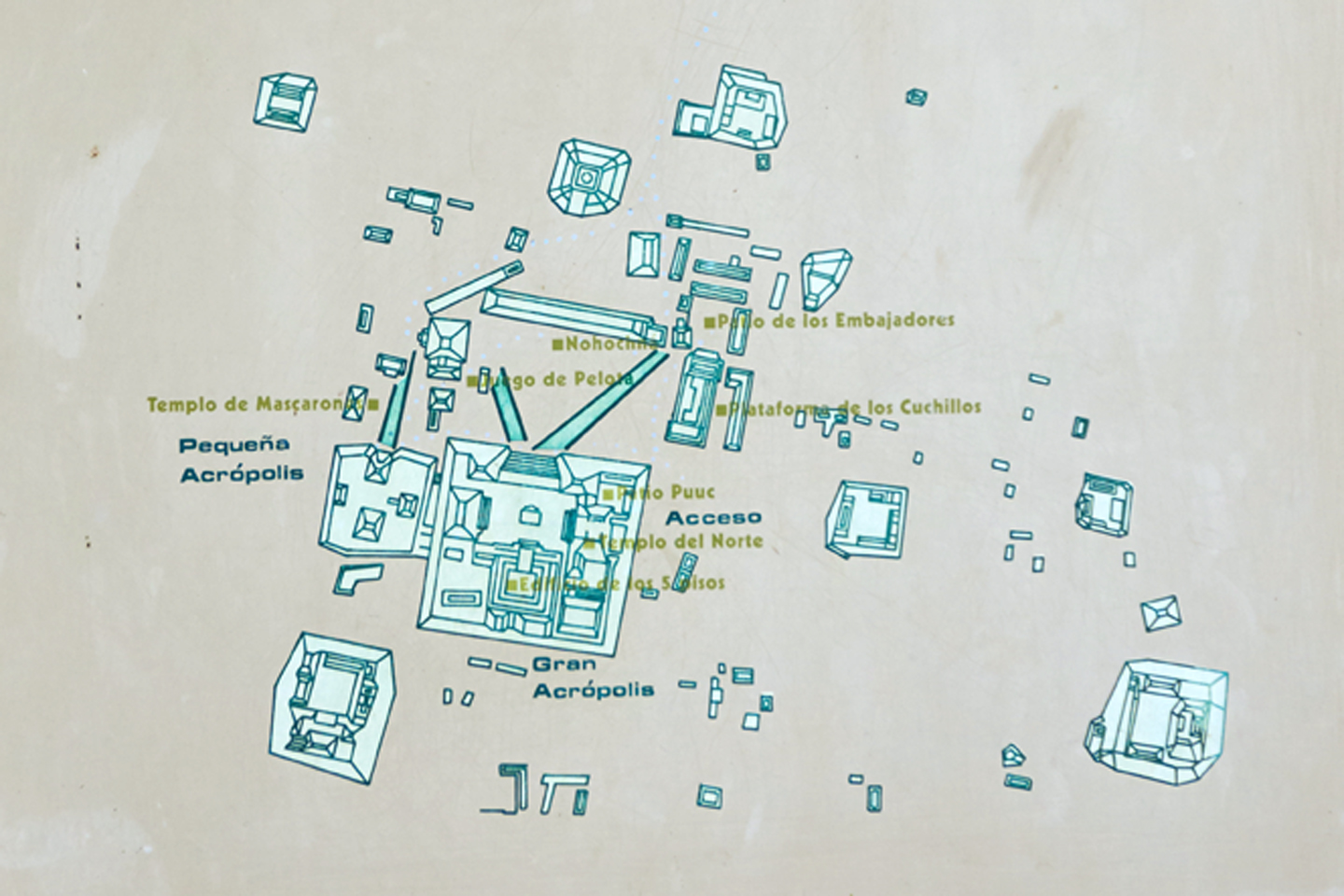

Much of Edzná’s well-preserved architecture is of the Puuc style, even though the city is located a fair distance from the Puuc Hills, where that method of building originated. Far more intriguing is the layout of the ceremonial center at the heart of this city, which mimics, albeit on a smaller scale, that of the great ancient metropolis of Teotihuacan, northeast of modern day Mexico City. As you can see in these satellite photos, the acropolis at Edzná follows the same basic plan, the same configuration, the same precise alignment with the cardinal points of the compass as it’s older, larger inspiration.

Satellite view of the acropolis at Edzná

Satellite view of the acroplis at Teotihuacan

The builders of these two centers came from entirely different cultures, and the construction took place in different eras, hundreds of years, hundreds of miles, and rugged mountain ranges apart. The similarities are simply too strong to write them off as coincidence, but the exact nature of the connection is a mystery. One more item on the growing list of things we’ll probably never know about the ancient Maya.

At the center of Edzná’s acropolis there is low stone structure known as the Solar Platform, which is precisely aligned on an east-west axis. A stepped altar is attached to the west end of the platform, and it’s believed that the structure was used to observe the sun’s position relative to certain markers. One day each year, on July 26th, the sun’s arc across the sky bisected their line just as it passed directly overhead. They marked that day as the beginning of their calendar year, and used the date in their calculatations of when to plant their crops, and when to hold religious and other festivals. It has been determined that other Mayan centers in the region used the date fixed by the priests at Edzná when setting their own calendars. If that’s true, the observations made in this spot had wide ranging importance.

Solar Platform, with the Temple of the Moon in the background. These structures were aligned for important celestial observations.

The most impressive accomplishment of Edzná’s builders is the extensive system of canals and reservoirs that surround the city’s core. The central feature was a navigable canal more than 150 feet wide and 7.5 miles long, with 31 feeder canals and 84 reservoirs. The system’s total capacity was 1.5 million cubic meters, and it served a variety of purposes: water for the community, irrigation for their fields, drainage during the rainy season, and water storage to help them weather the dry season. Barges and canoes transported goods along the canals, side branches were used for fish farming, and if the city came under attack, the canal system worked like a moat, to aid in their defense. Edzná’s temples and pyramids are remarkable, lasting monuments to the once mighty civilization that both rose and fell here, but there’s more going on than what meets the eye. Without the pulse and flow of the waterworks, none of it would have been possible.

The Acropolis at Edzna, anchored by the Castle of the Five Floors

In terms of style, Edzná was a bit of a mongrel, borrowing elements from far and wide, but putting their own stamp on them, and achieving a level of perfection that is remarkable, even to this day. We can only imagine how it must have looked when this was still a living city. Like virtually all the important Mayan ceremonial centers, Edzná was abandoned long before the Europeans arrived, so there are no first hand accounts. What little we do know of Edzná’s past, the succession of ruling dynasties, the alliances, the wars that were fought, all of that was deciphered from the commemorative stelae and other glyphs found at the site.

The city’s history, from the time of its founding to the time when it faded into abandonment spans a period of 2,100 years. longer than almost any other in the Mayan world. There’s more digging to be done, and much more to be discovered as the archaeologists peel back the layers of time, and expose the secrets of Edzná’s legacy.

Any discussion of the pre-history of this area begs the obvious question: how could a civilization as complex, as widespread, and as long-lived as that of the Maya just disappear? Answer: it didn’t. At least, not all at once. Blame climate change for breaking up the high density population centers, but the people didn’t all die off or move away. Smaller groups of them spread out through the area, subsistence farmers, living much as they always had, in scattered hamlets and homesteads. What disappeared was all the high drama, the pomp and the grandeur, the art, the architecture, the priesthood, the warrior caste, and the pampered nobility. As for the pyramids, they had no further need for the bloody things, so they just let the jungle swallow them up.

Temple of the Witch. Mayan pyramids require constant maintenance to keep them clear of encroaching vegetation.

VISITING EDZNÁ

On my most recent trip to Mexico, back in 2015, we made a complete circuit of the Yucatan Peninsula, beginning in Merida and traveling clockwise, on the hunt for Mayan ruins. Over the course of a week, we’d stopped at quite a few, including several of the Rio Bec sites in Quintana Roo. From Chetumal, on the border with Belize, we drove west, headed for the Mayan cities along the Puuc Route. We stopped for the night in Escarcega, and the next day, on our way to Campeche, I decided to take a detour, to check out this place I’d noticed on my map. I’d never heard of it before, but I liked the name: Edzná (pronounced just like it’s spelled). As it turned out, there was quite a lot to like about Edzná!

A tip for photographers: Try to get to the park just as it opens at 8 AM. That’s when you’ll have the best light, and the smallest likelihood of crowds.

Edzná gets fewer visitors than the better-known Mayan cities, so the amenities are minimal. No fancy entryway. Just a sign and a path that leads to the kiosk where you pay your admission fee. There’s a small museum, and restroom facilities, but there’s no souvenir shop, and no restaurant. You can bring your own water, but no other food or drink from outside the park. A limited selection of snacks and drinks is available for purchase at the visitor’s kiosk.

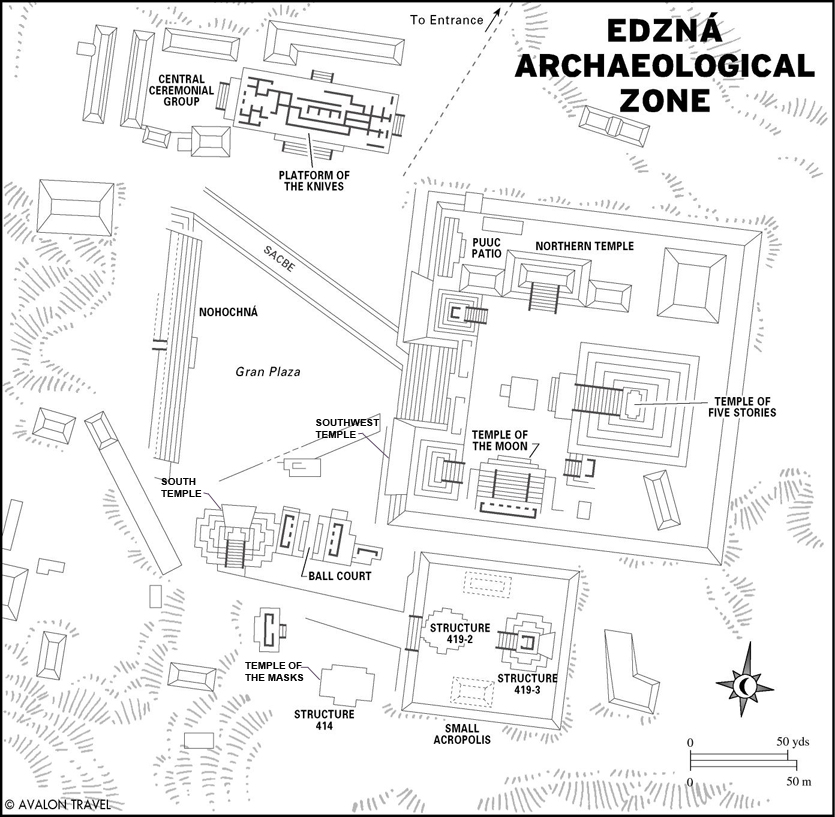

The Edzna Archeaological Park as it exists today.

Click for an expanded view of all maps and photos

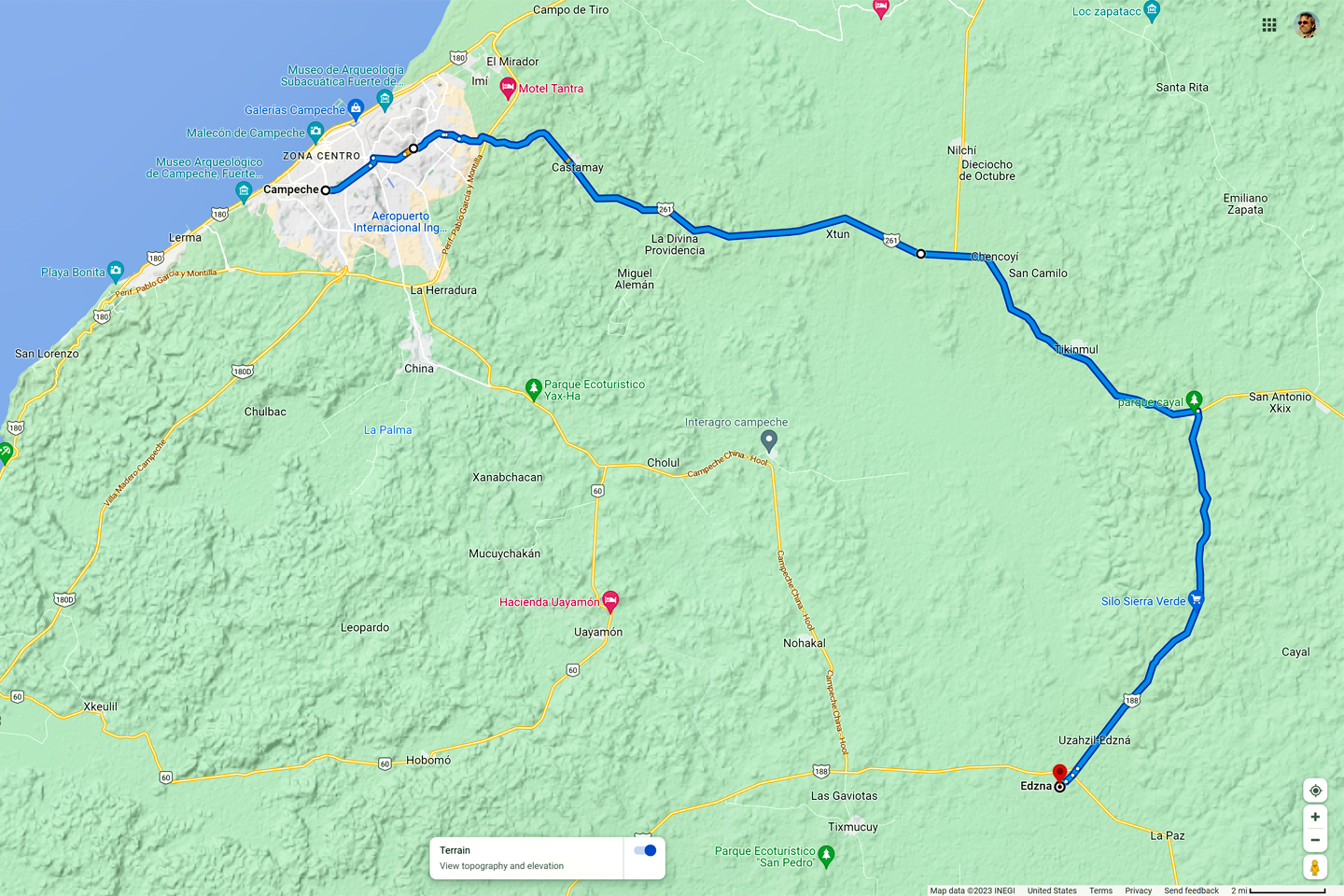

Most visitors to Edzná come from Campeche. There are a number of tour operators in the city who will be happy to transport you to the park and guide you ’round the ruins for a fee. It’s also fairly simple to do it on your own, by renting a car. It’s a very easy drive on decent paved roads, an hour or so in each direction, following MX 261 for 45 km east to MX 188, and then taking that road another 18 km south to Edzna, with well marked signage all along the route. When you arrive, there is ample, reasonably secure parking at the site.

When driving in Mexico, it’s recommended that you stay on the Cuotas, the toll roads, which are better maintained and considered safer for travelers. The roads between Campeche and Edzna are NOT toll roads, but in this case, there is no better option. State highways are slower than the federal toll roads because they carry more local traffic, and they travel through the middle of all the tiny towns. They’re more picturesque, but most definitely more dangerous, with livestock and numerous other hazards in the middle of the highway, and brutal over-sized speed bumps (topes) serving as passive traffic enforcement. As long as you’re not in a hurry, it’s all part of the adventure!

A third option is to hire a taxi for the day; they’ll take you to Edzná, wait for you, and then take you back to Campeche. (It’s usually best to make those arrangements through your hotel). No matter how you get out there, this is a very easy day trip from Campeche, and well worth your time.

If you’re starting from Merida, I would recommend making Edzná a two day excursion, with a night spent in Campeche, a wonderful destination in its own right. (See my post on this site: Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha!)

For more tips on driving in Mexico, see my post: Mexican Road Trip: How to Plan and Prepare for a Drive to the Yucatan

There were literally no other visitors during the entire time we were there, which was a fantastic experience, and unusual, even for a lightly visited place like Edzná. This was mid-October, still the rainy season, so still the off-season for tourist destinations in southern Mexico. We did see a fair amount of rain on our trip, but it didn’t cause us any serious problems, and the lack of crowds was very much to our advantage.

I’m told that weekends and holidays tend to be the busiest times at Edzná, particularly in the summer, when schools are not in session. If you’re planning a visit, that might be something to keep in mind.

EXPLORING THE RUINS

Entrance to the Archaeological Park is just 85 Pesos per person, about $4.50 US, which is a bargain when compared to Chichen Itza and Uxmal (both more than $25 per person, when you add in all the extra fees). The ancient city of Edzná covered almost 10 square miles, and there are unexcavated structures throughout that area. Even so, it’s the ceremonial center at the heart of the complex that draws the greatest interest, and that’s what you’re paying to see.

In the 1980’s, a major excavation and restoration project was undertaken in the northern section of the complex, and a large number of Guatemalans who had fled the civil war in their country were hired to do the work. Several European ambassadors took a personal interest in what was seen as a humanitarian effort to aid those refugees, and they were instrumental in rallying support. Preservation of the monuments was the nominal goal, but in this case, it was more of a bonus.

The restored structures in this sector are the first that you see when you enter the park.

You walk into a grassy tree-shaded courtyard surrounded by stone buildings. At the center, there is a low circular platform with two smaller circles attached; an altar of indeterminate purpose. The courtyard was renamed to honor the men who made it possible; it is now known as:

THE COURTYARD OF THE AMBASSADORS

There are interesting structures in every direction, altars, temples, palaces and stairs. It’s all worth a closer look, but you probably won’t linger all that long on your first pass, because there are much bigger things to see, just beyond the trees.

A circular platform, possibly an altar, at the center of the courtyard. The two smaller circles positioned side by side with the larger circle had ritual significance, but their exact function has not been determined. Look beyond the circular altar, and up one level in the courtyard and you’ll see the remains of the Circular Temple, an unusual structure that may have been associated with Ehecatl, or possibly Hunraqan, the Mayan Gods of the Wind.

The platform of the knives, so-called because of an offering of stone blades that was found buried there. The overall structure is quite large, 80 meters long by 35 meters wide, rising as much as 5 meters above the level of the courtyard, and there are steps on all four sides. Evidence shows that these were elite residential quarters.

A smaller altar, featuring a stone carved into the shape of a serpent’s head, a common religious motif.

The Courtyard of the Ambassadors: The Circular Altar is in the foreground, while the structure known as the Southwest Palace, with its distinctive columns, is just beyond.

NOHOCH-NÁ

As you leave the courtyard and enter the grassy expanse of the Grand Plaza, to your right there is a massive structure known as the Nohoch-Ná, literally, the “Big House,” a stepped platform that is 443 feet long, 102 feet wide, and 30 feet tall, built in the Peten Style of Mayan architecture, which features stepped terraces, prominent staircases, and walls with rounded corners. There are fifteen massively wide steps that climb the entire eastern side of the structure, steps that may have been used as seating for events in the plaza. The western side is different, with terraces and smaller staircases leading to the top, where there are four galleries running between stone walls, with evidence of 48 separate doorways leading into as many seperate interior rooms. Additional evidence suggests that the rooms were used for administrative rather than residential purposes; perhaps for the storage and distribution of elite luxury goods.

Three views of the Nohoch-Na, which stretches along the entire western side of the Grand Plaza.

THE GRAND PLAZA

When Edzná was a living city, the Grand Plaza would have been a gathering place, where people came together for festivals, celebrations, religious observances, and other important events. The stone borders of the sacbes, the limestone pathways that connected different parts of the city, are still visible, running across the open space toward the steps leading up to the Grand Acropolis, which rises above the east side of the plaza.

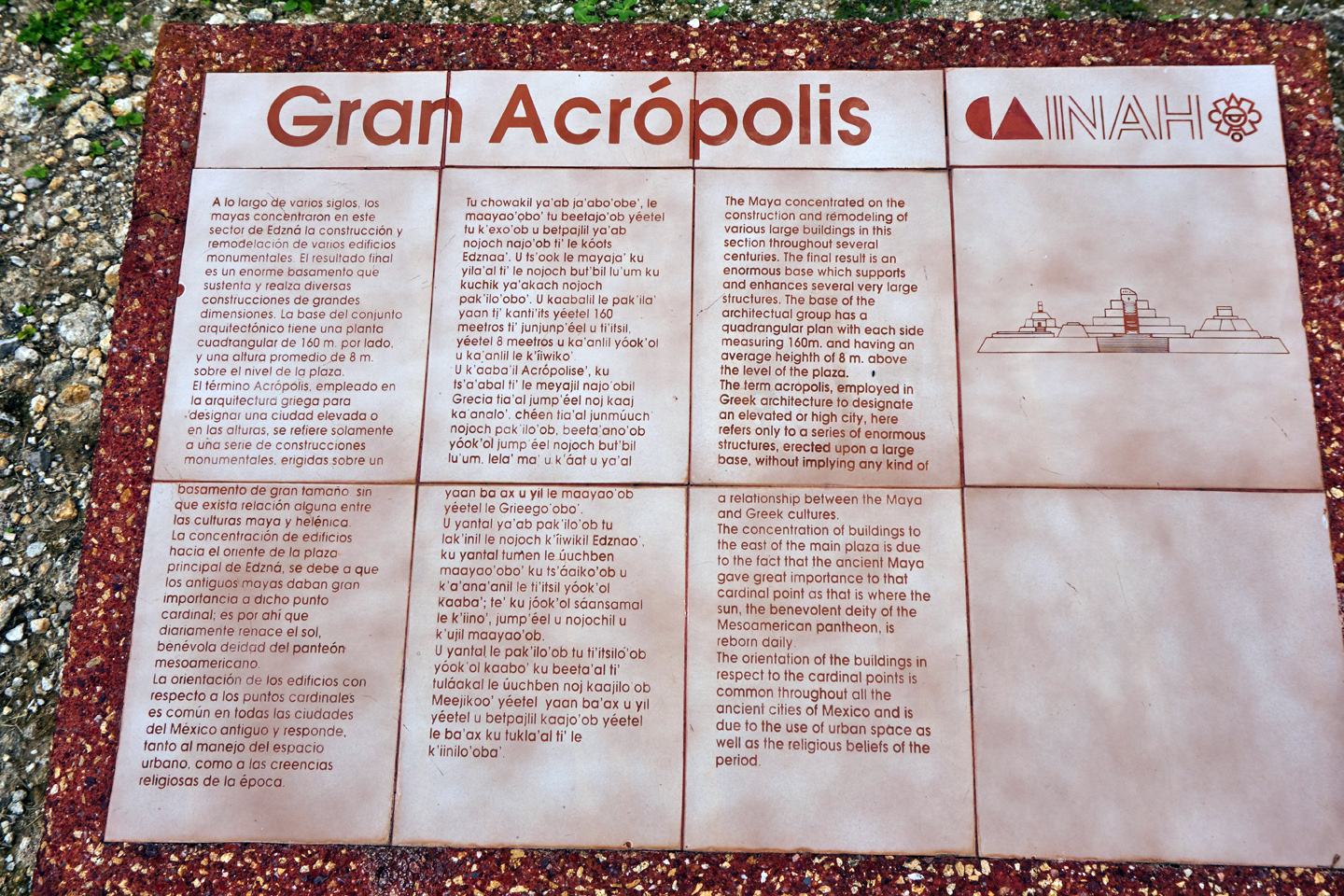

THE GRAND ACROPOLIS

The Acropolis is a ceremonial complex built atop an enormous platform, 525 feet on each side, and 26 feet above the level of the Grand Plaza. The Castle of the Five Floors dominates the scene, but there are major temples on every side, and a wide stone staircase leading from the Grand Plaza up to the central courtyard. Those who had business at the Castle or the Temples would follow the sacbes to these steps. The intent was to make sure those approaching knew their place: in this setting, an ordinary human feels very small.

THE CASTLE OF THE FIVE FLOORS

Curving stone buttresses beside the steps on the back side of the Castle of the Five Floors

The largest building at Edzná, the primary structure at the head of the acropolis, is a palace, or temple, with five distinct stories, crowned by a massive Peten style roof comb that pushes the height to more than 110 feet. Taller than a 10 story building, the top of the castle and its decorative comb is visible from a considerable distance. When the building was in use, the comb was covered in stucco and painted red, rising above the treetops like a beacon, serving as an invitation to approaching friends, or a warning to approaching strangers.

Variously known as The Castle, The Palace, The Temple, or simply, The Building of the Five Floors (or Stories, or Levels), there are 22 vaulted interior rooms in the structure, with 5 more in the temple that serves as a top floor. There’s a magnificent grand staircase on the front, western side of the building, leading from ground level all the way to the top, while the back side is buttressed by unusual, elegantly curving stone structures that showcase the skill of the Mayan stonemasons. My personal theory (based on nothing but my active imagination): the curved surfaces served as ramps, with landings, making it easier when using ropes to haul loads to the top of the structure. The walls on the front side are made of built-up concrete, faced with cut stones that form a veneer; a Puuc style construction technique that allows more spacious interiors. It’s likely that at least some of these rooms were used as residences for the city’s elite.

Five views of the Castle: from the front, the side, and the rear, showing the Grand Staircase and the stone buttresses. The roof comb, originally covered in stucco and painted bright red, soars an additional 19 feet above the top of the building. The tenons projecting from the comb served to support a thick layer of molded plaster.

On the two lowest levels, sections of the grand staircase are supported by platforms of cast cement that create an arch, a configuration known as a “flying staircase.” I assume these were reinforced during the restoration, but even if they were, visitors are not allowed to climb those stairs. When I was there, no staff was around to enforce that rule, but as much as I would have loved to see the view from the top, there are good reasons for the restrictions. These buildings are very old, and too many trampling feet would cause damage.

HIEROGLYPHIC STAIRCASE

The risers of the stairs at the base of the Castle of the Five Floors are faced with panels featuring carved stone glyphs. There were a total of 86 of these hieroglyphic panels on the staircase. Among those that are still legible is a Long Count date glyph corresponding to the year 652 AD. That might represent the date that construction was completed; then again, it might not. The Maya commemorated dates for a lot of different reasons, and these glyphs are small pieces of a much larger puzzle that archaeologists have only just begun to resolve.

TEMPLE OF THE MOON

On the south side of the acropolis, a truncated pyramid known as the Temple of the Moon rises an additional 26 feet above the courtyard. 131 feet long by nearly 100 feet wide, the temple features a broad central staircase flanked by the six ascending tiers that make up the body of the Peten style pyramid, which, at this time, is only partially excavated.

SOUTHWEST TEMPLE

Another impressive structure rising from Edzná’s acropolis is the Southwest Temple, a massive, Peten Style pyramid that anchors the southwest corner of the ceremonial complex. The body of the massive, blocky pyramid dates to the Early Classic period. There were four small rooms at the top that were built during the Late Classic, several hundred years afterward. Multiple phases of construction are typical of these monumental structures.

NORTH TEMPLE

The north side of the Acropolis is occupied by the North Temple, a building that combines several different types of Mayan Architecture.

The original structure was a Peten Style pyramid with a wide staircase in the center. At some point, the left and right portions of the staircase were covered by sloping, ramp-like structures that reduce the width of the stairs. Their exact purpose is unknown, but they may have been used when hauling materials to the top of the building during later construction phases. Those sloping structures are of the Puuc architectural style, while the temple at the top of the structure has decorative elements of not just the Puuc, but also the Chenes and Chontal styles of building.

BEYOND THE GRAND ACROPOLIS

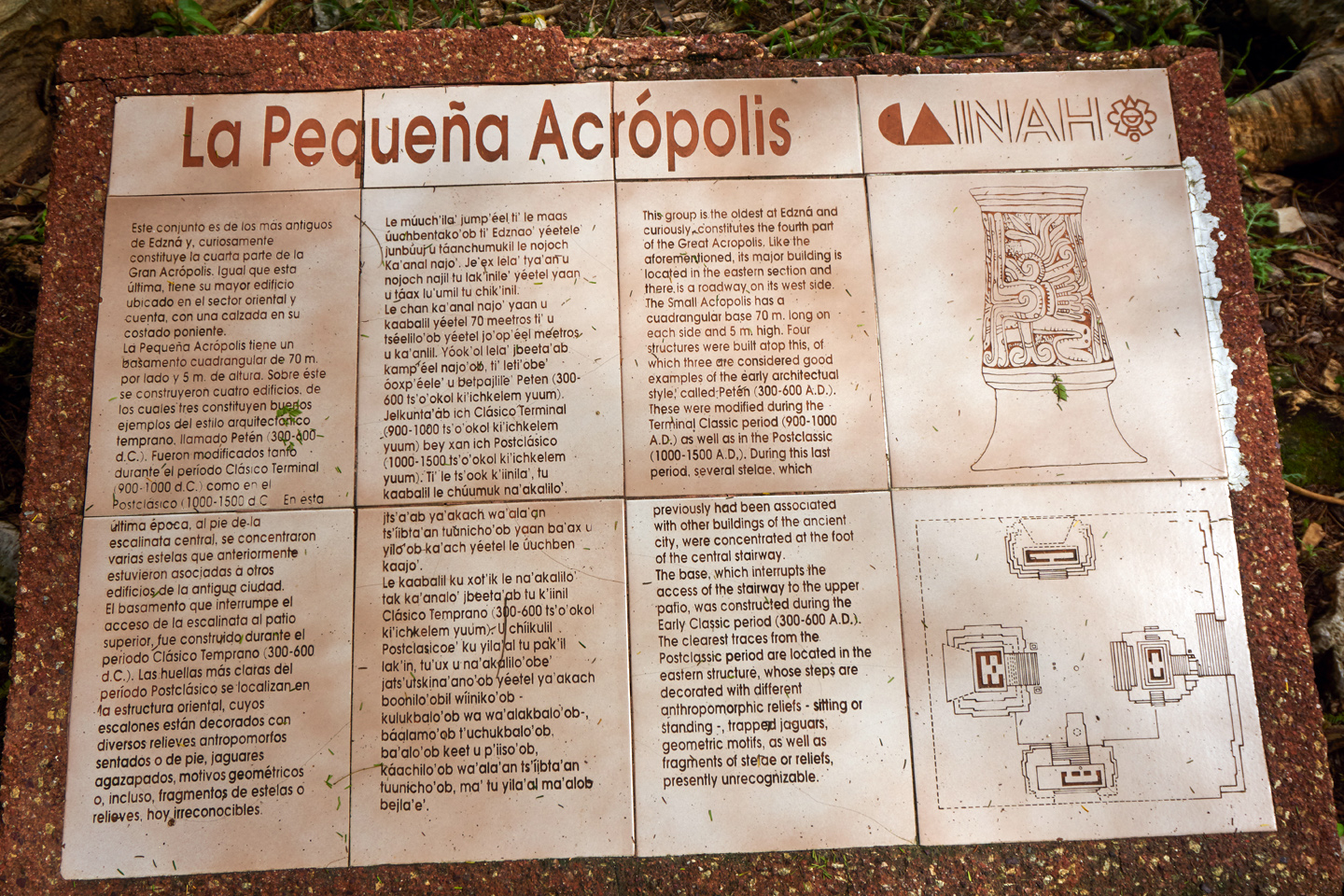

SMALL ACROPOLIS

Immediately to the south of the Grand Acropolis is a smaller ceremonial complex known as the Small Acropolis, a grouping of four buildings arranged around a courtyard, all built atop a platform that is 70 meters on each side, and 5 meters above the level of the Plaza, with broad steps leading up.

The structures grouped around the Small Acropolis are some of the oldest surviving buildings in Edzná, some sections having been constructed in the Pre-Classic era, prior to 300 A.D. The complex pre-dates the Grand Acropolis by several hundred years.

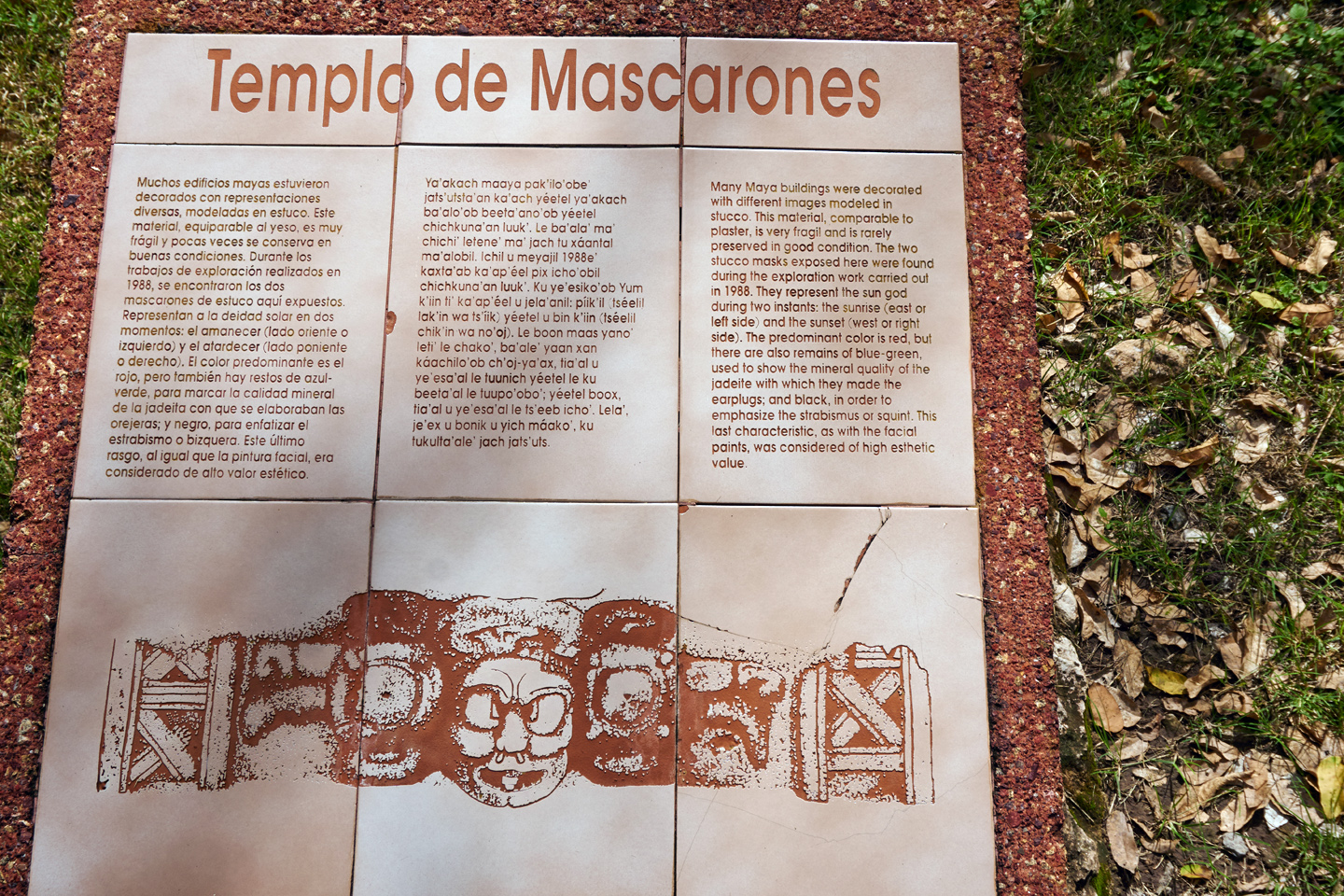

TEMPLE OF THE MASKS

Immediately to the west of the small acropolis is a low structure known as the Temple of the Masks, named for the two large stucco masks that were located on either side of the north facing stairway. What you see today are the remains of the original Peten-style building, which was at the core of a more recent larger structure that has since crumbled away.

The stucco masks were first brought to light during excavations conducted in 1988, and they were a very pleasant surprise. Molded stucco was a common decorative element on Mayan buildings, but it’s extremely fragile, so very few examples have survived in good condition.

These masks at Edzná are quite rare; among the best that have ever been found. The thatched roof palapa that you see in the photo was added to protect the display from the weather. The masks represent the two faces of K’inich Ajaw, the Mayan sun god, one on the east side as he appears at the moment of sunrise, the other on the west, when the sun sets. These were originally painted, primarily red, with elements of blue, green, black, ochre, and purple. As with every Mayan sculpture, every decorative element has meaning, so these masks, while similar, have very important differences. The noses are missing on both masks, the only significant damage to these delicate plaster sculptures. That’s remarkable, considering their size: each mask is more than 3 feet tall, and 10 feet wide.

Click the pictures (below) to expand them. Click again to see an instant Photoshop fix for the missing noses. ![]()

The eastern mask faces the rising sun

The western mask faces the setting sun

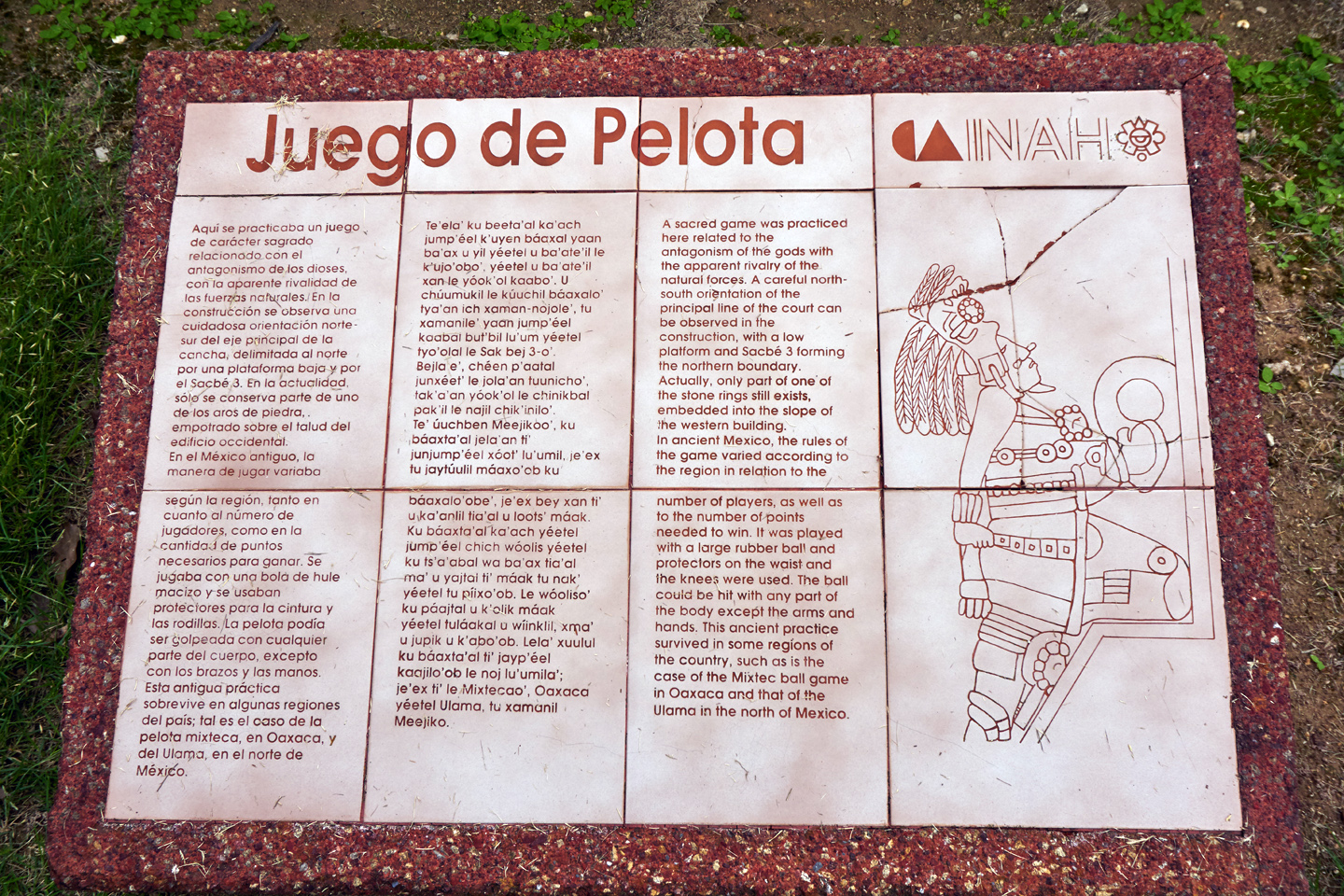

BALL COURT

Like every Mayan city of any size, Edzná had a ball court, used for a game that was more ritual than sport. When the court was in use, stone rings were set into the sloping walls of the structures on either side of the court. Players used leather armor to protect themselves from the heavy rubber ball, which they had to knock through the goal ring using only their elbows, knees, and hips. The game was deadly serious, often used as a way to settle disputes between rival factions, or rival cities. In at least one version, players on the losing team were beheaded, as a sacrifice to the gods.

The ball court, partially restored, missing the original goal rings. When in use, the sloping sides were smoothly stuccoed.

SOUTH TEMPLE

Adjacent to the ball court, there is a large, Peten-Style stepped pyramid known as the South Temple. This is a very old structure, built over the top of an even older structure dating all the way back to the Pre-Classic period, when Edzná was just getting started. There are rooms atop the five-level pyramid, including an “inner sanctum” where private rituals could be performed, out of the public view.

STELAE

A total of 32 commemorative stelae have been recovered at Edzna, and most of them are on display in the small museum by the entrance kiosk. These stelae, along with the glyphs on two sets of hieroglyphic stairs, two lintels, and a hieroglyphic panel have provided researchers with a wealth of information about the dynasties that rose to power in Edzná, the names and titles of the rulers, the dates of their accession, battles fought, and alliances with other Mayan city states. Most of the stelae date to the Late Classic period, from 600 to 900 AD, when Edzná was at its peak.

Click any photo to enlarge.

CURRENT RESIDENTS

Every Mayan ruin that we stopped at, from the large, crowded sites like Chichen Itzá to the smaller sites like Edzna, they all had one thing in common: they’re crawling with Iguanas! Mexican Spiny Tailed Iguanas, Black Spiny Tailed Iguanas, and Yucatan Spiny Tailed Iguanas, just to name a few. When the Mayans moved out, the Iguanas moved in, and they’ve made themselves very much at home among the ruins.

I’ve never been a bird watcher, but I am a bird lover, and I’ve always enjoyed taking pictures of them, even when I don’t have a clue as to the species. After-the-fact identification has never been easier: drag and drop just about any bird photo into the Google search bar, and nine times out of ten, you’ll get a hit. In this case, it took the search engine all of half a second to identify the trio of flycatchers in my photo from Edzná: they are Greater Kiskadees, a species that ranges from Texas all the way south to Argentina–including the Yucatan. Pretty cool!

Edzná is a fantastic place to visit. Mysterious ruins, rising up out of the jungle, and with the minimal crowds, you can really feel the presence of the ancient Maya. We can only imagine what it would have been like when it was still in use, with all the sights, sounds, and smells of a living city teeming with people, with the kings and nobles in their palaces, and the priests in their temples. What a different world that was, and not so very long ago.

Click the button to launch a Full Screen slide show featuring an assortment of my favorite photos from Edzná. These super-sized slides are best viewed on a full sized monitor or a tablet. They’re not properly configured for a Mobile browser.

Note: This is a revised and expanded version of a previous post that was titled: The Extraordinary Mayan City of Edzná

Unless otherwise noted, all of these photographs are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

IF YOU’D LIKE TO DIG A LITTLE DEEPER:

If you’re looking for more detailed information about Edzná, I highly recommend the book Edzná: A Pre-Columbian City in Campeche, by Antonio Benavides Castillo. The book is currently out of print, but if you’re unable to find a copy in your local libary, I have an alternative recommendation: Jim Cook is a travel writer based in Mexico, and in his blog, Jim & Carole’s Mexico Adventure, he’s created a nicely done eight part series about Edzná that draws heavily from Benavides Castillo’s work.

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

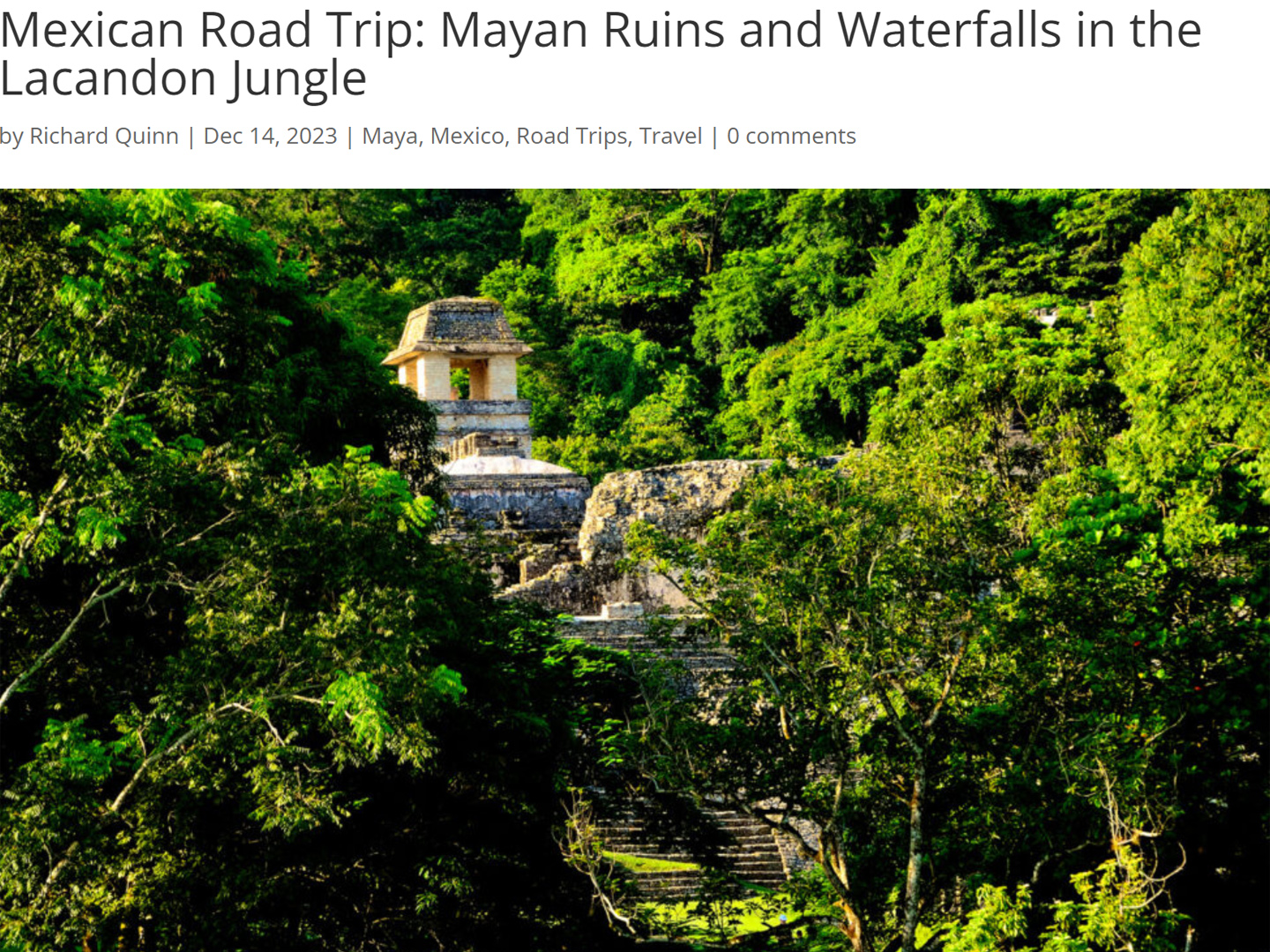

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

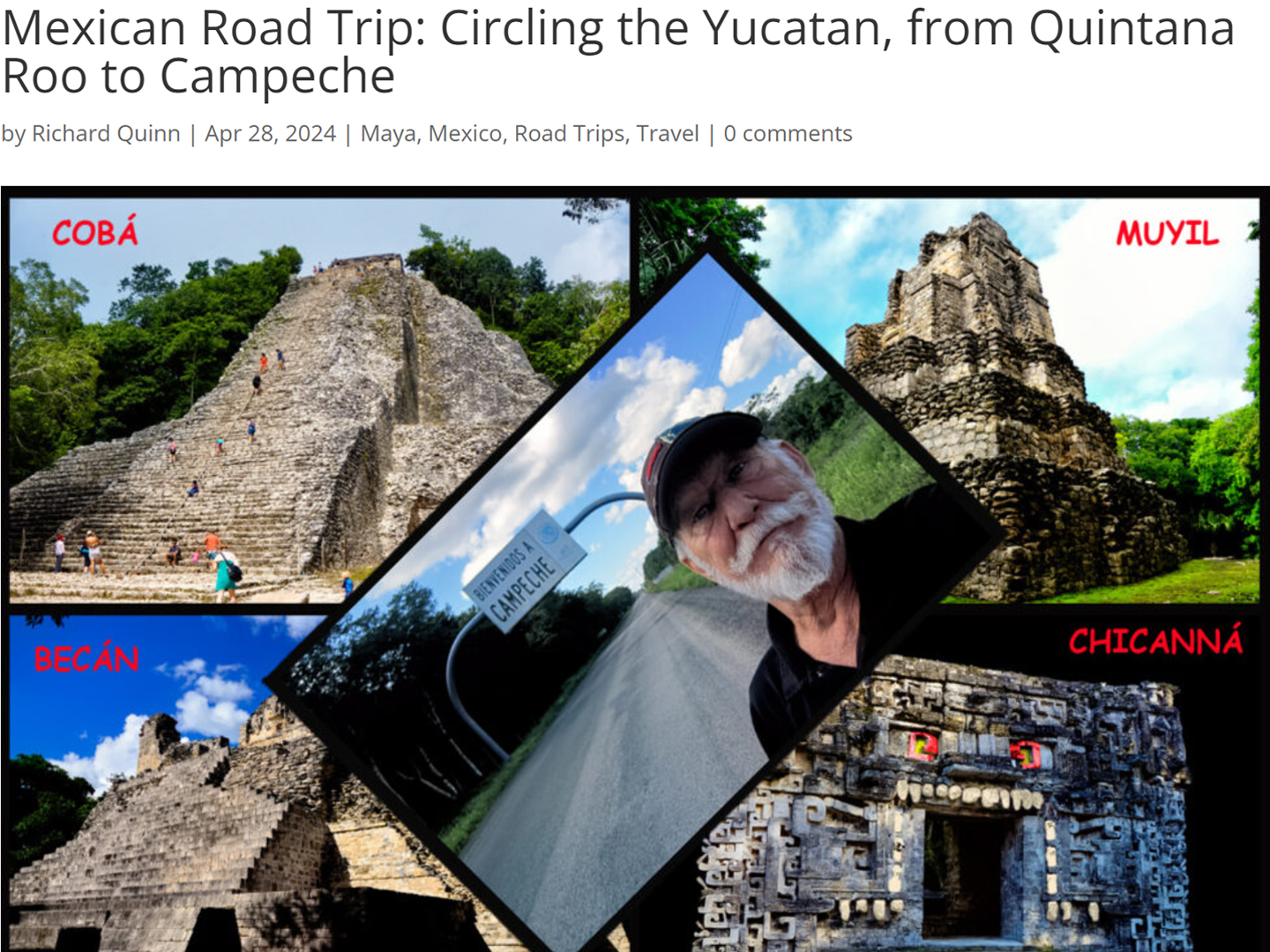

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn’t huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

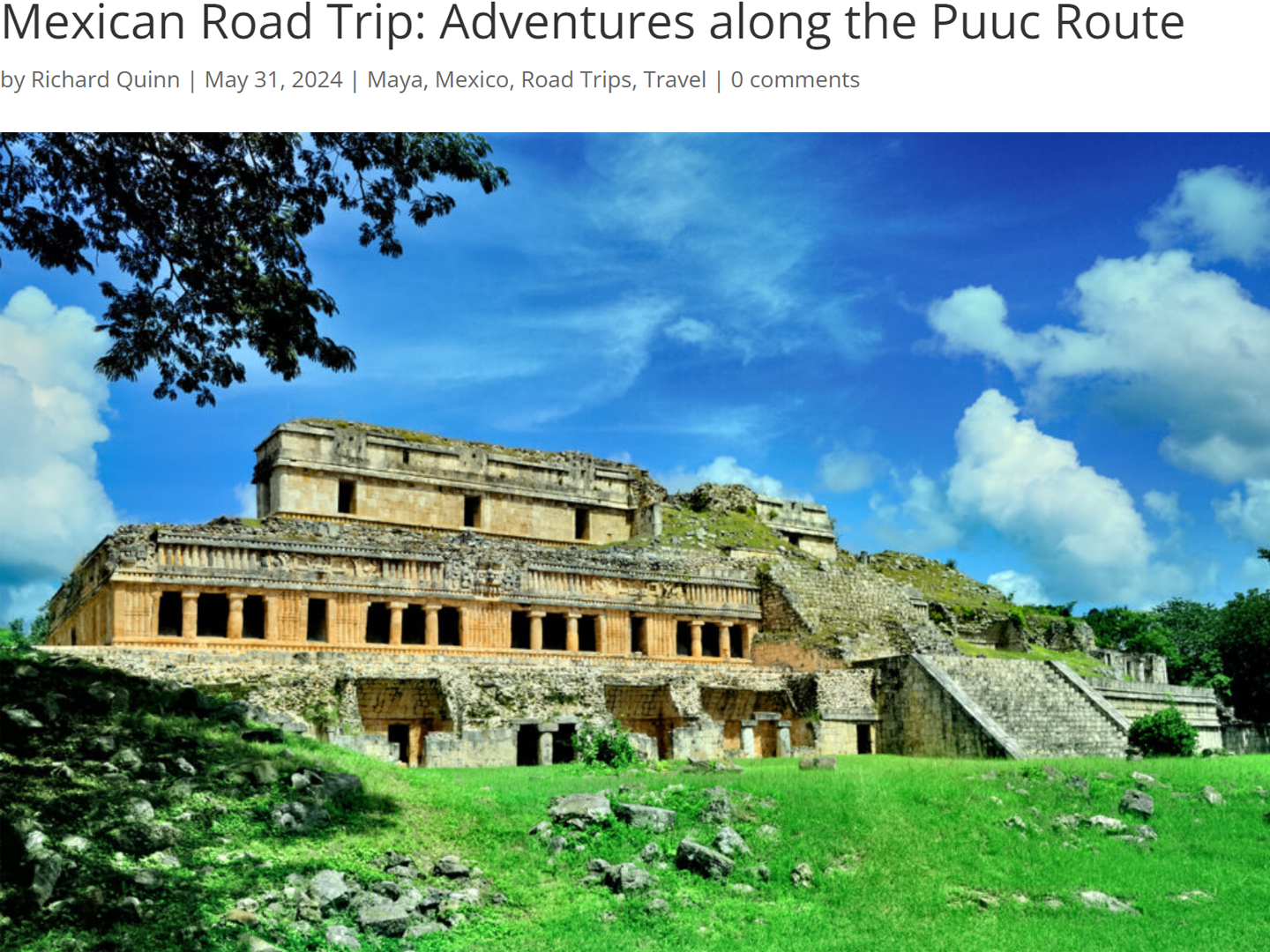

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

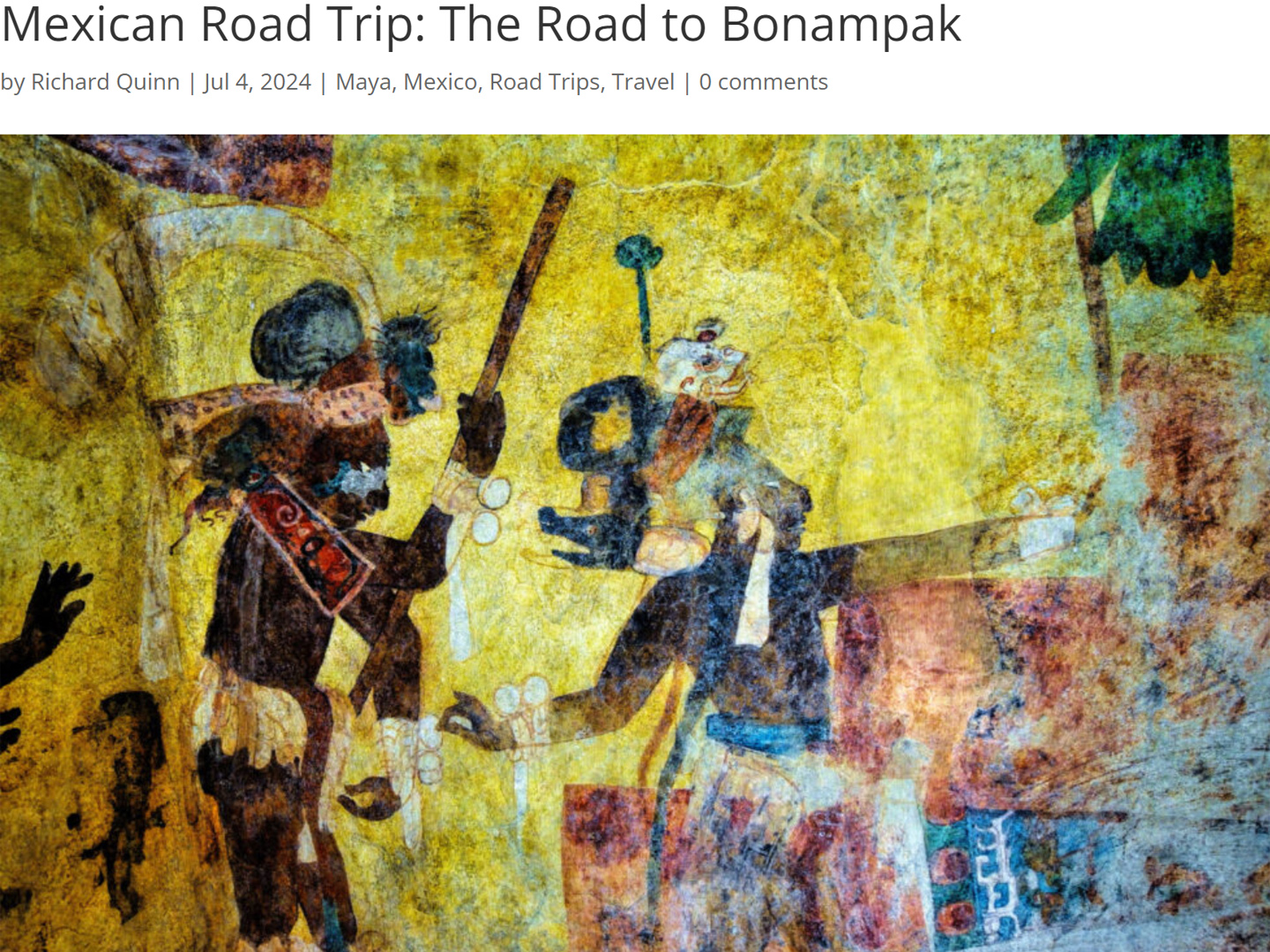

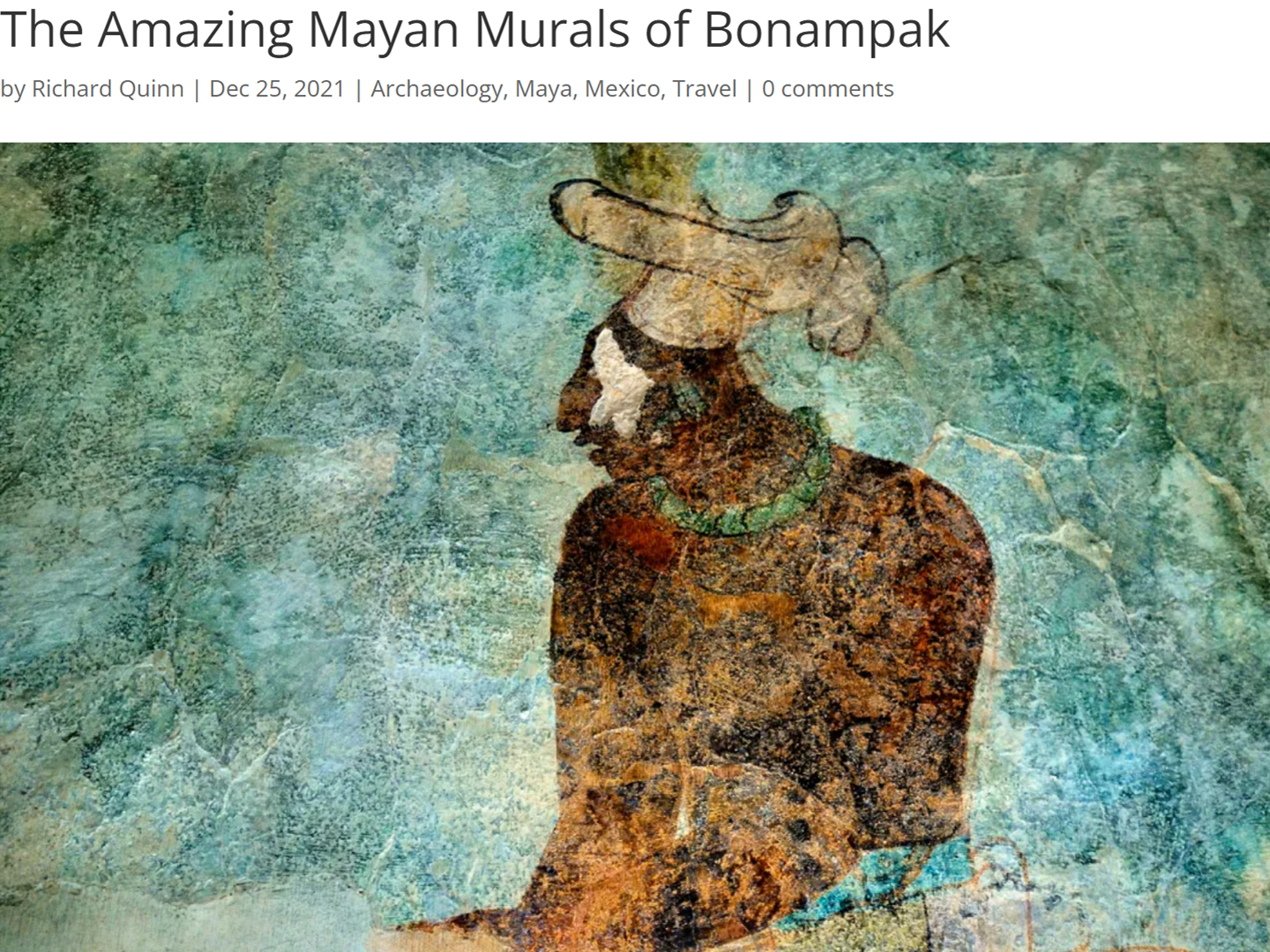

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we’re left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it’s 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in March, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

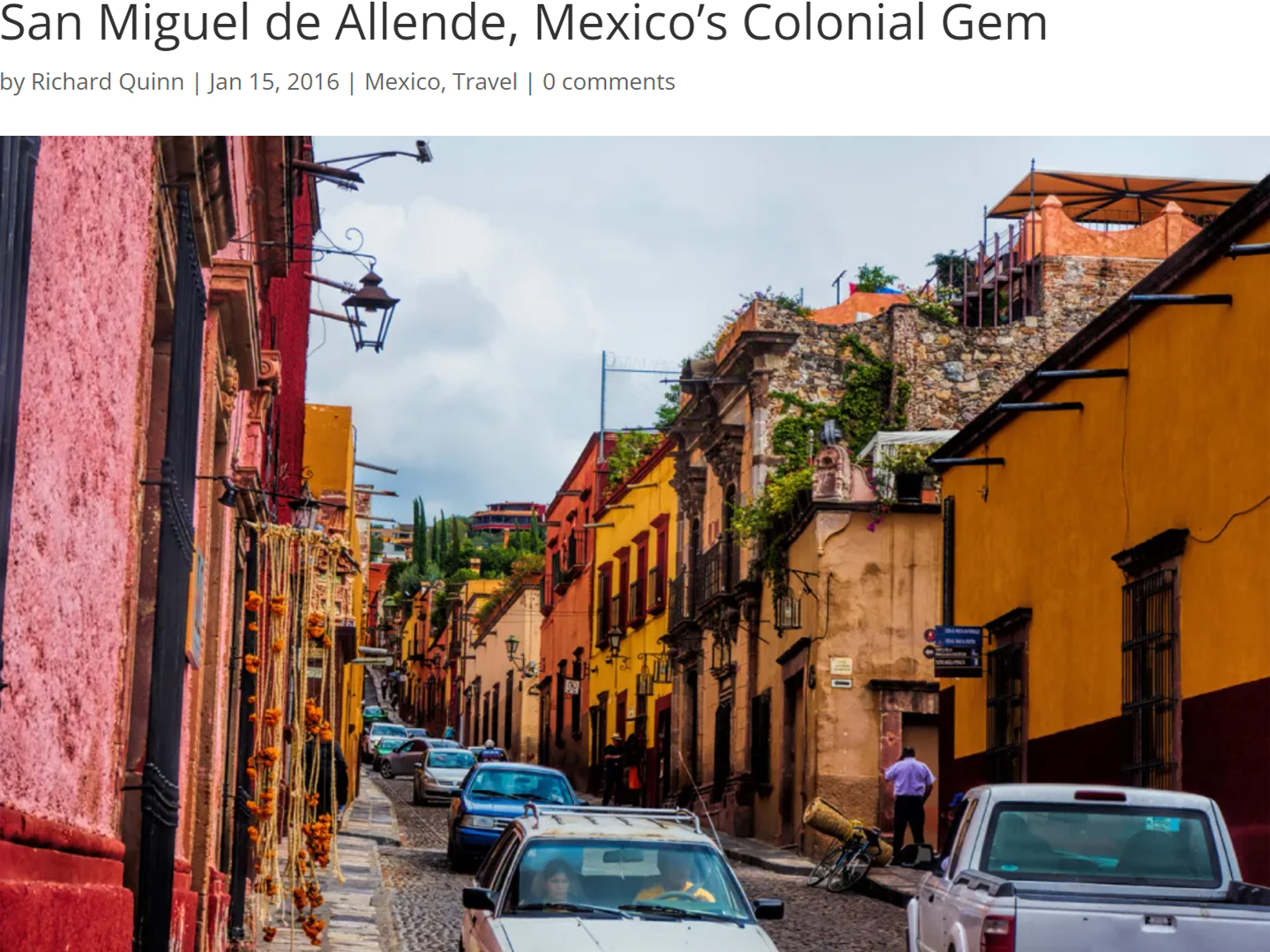

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico’s Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they’ve adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It’s a wonderful, colorful parade that’s all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

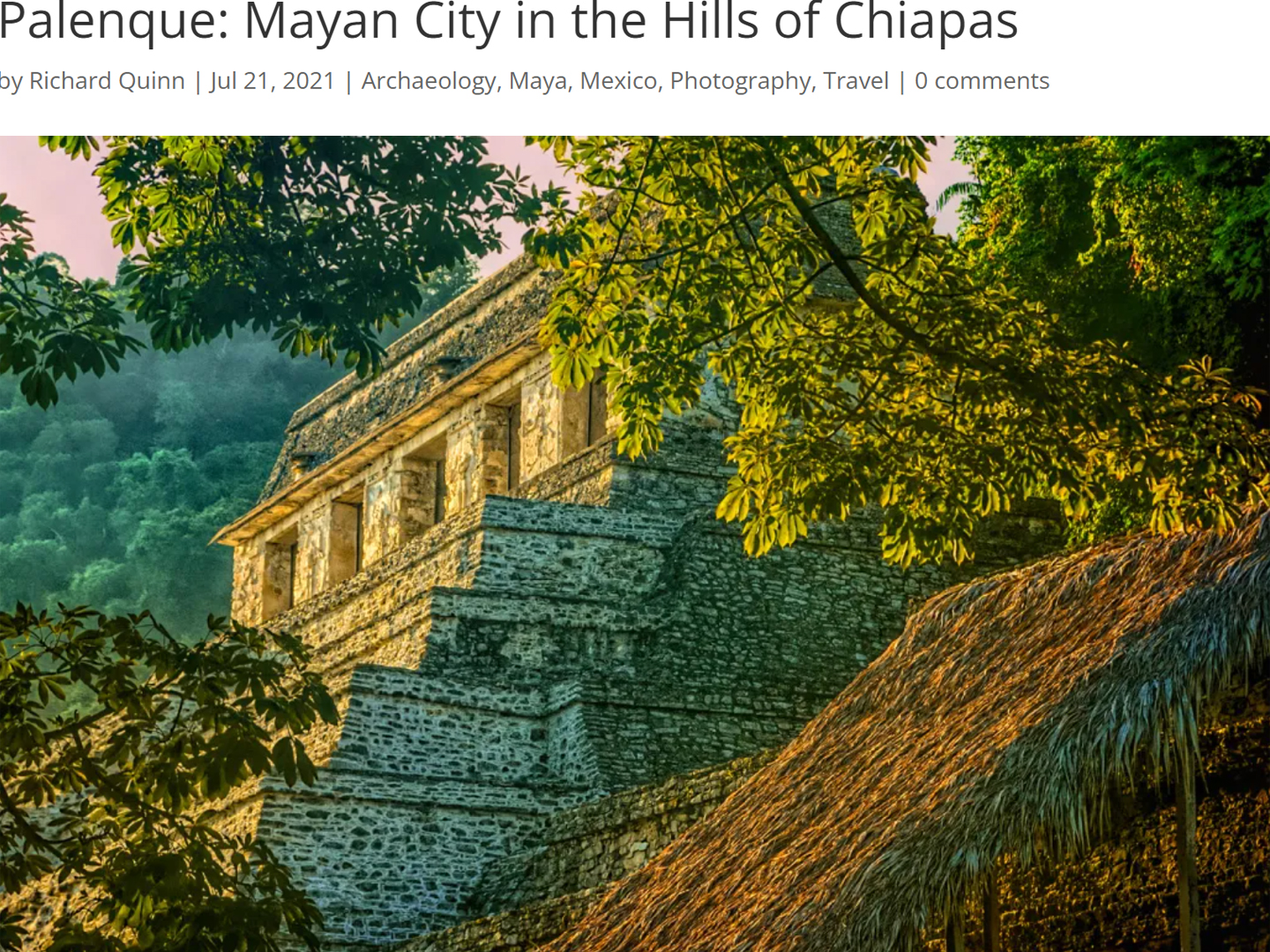

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

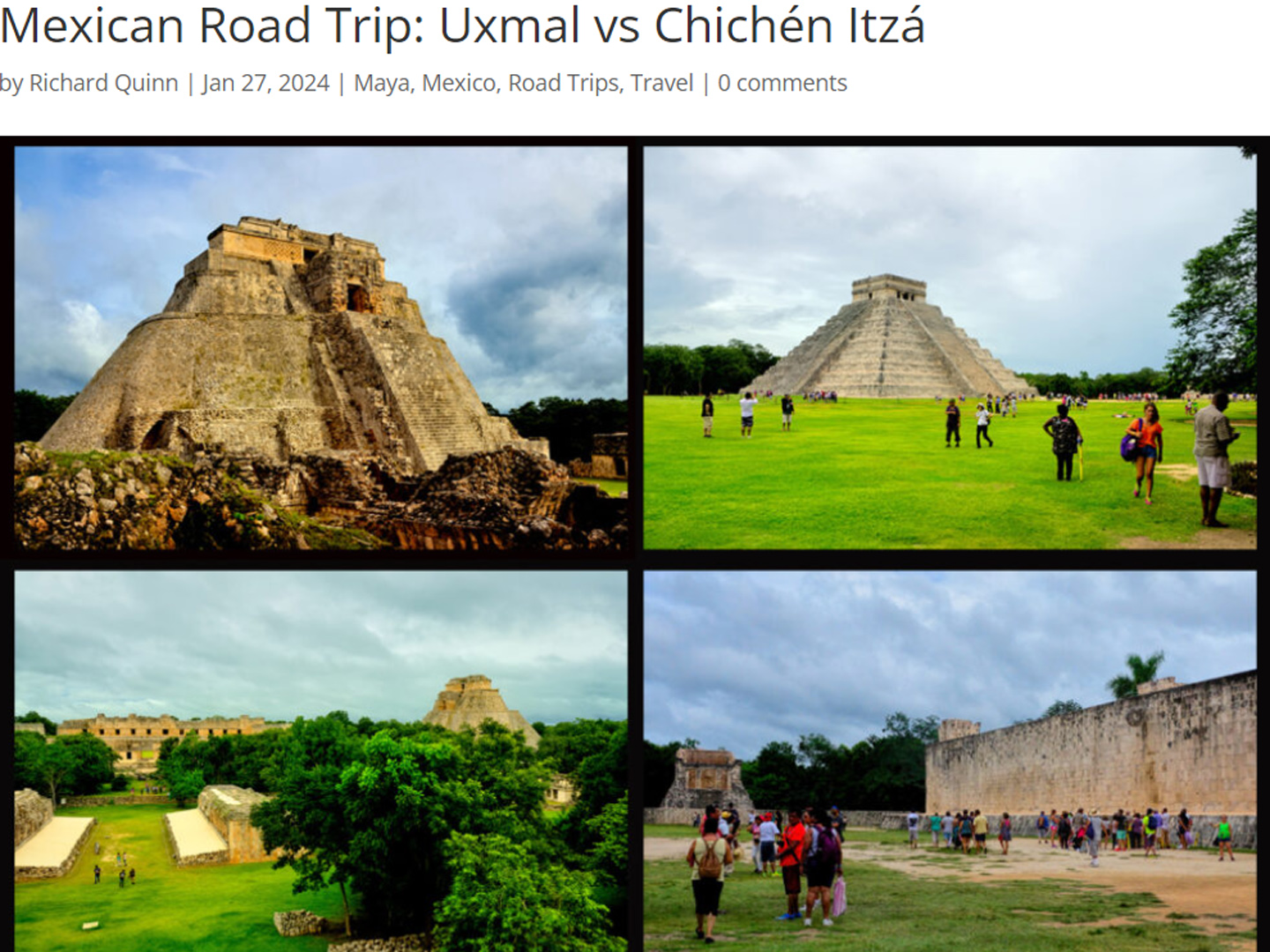

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

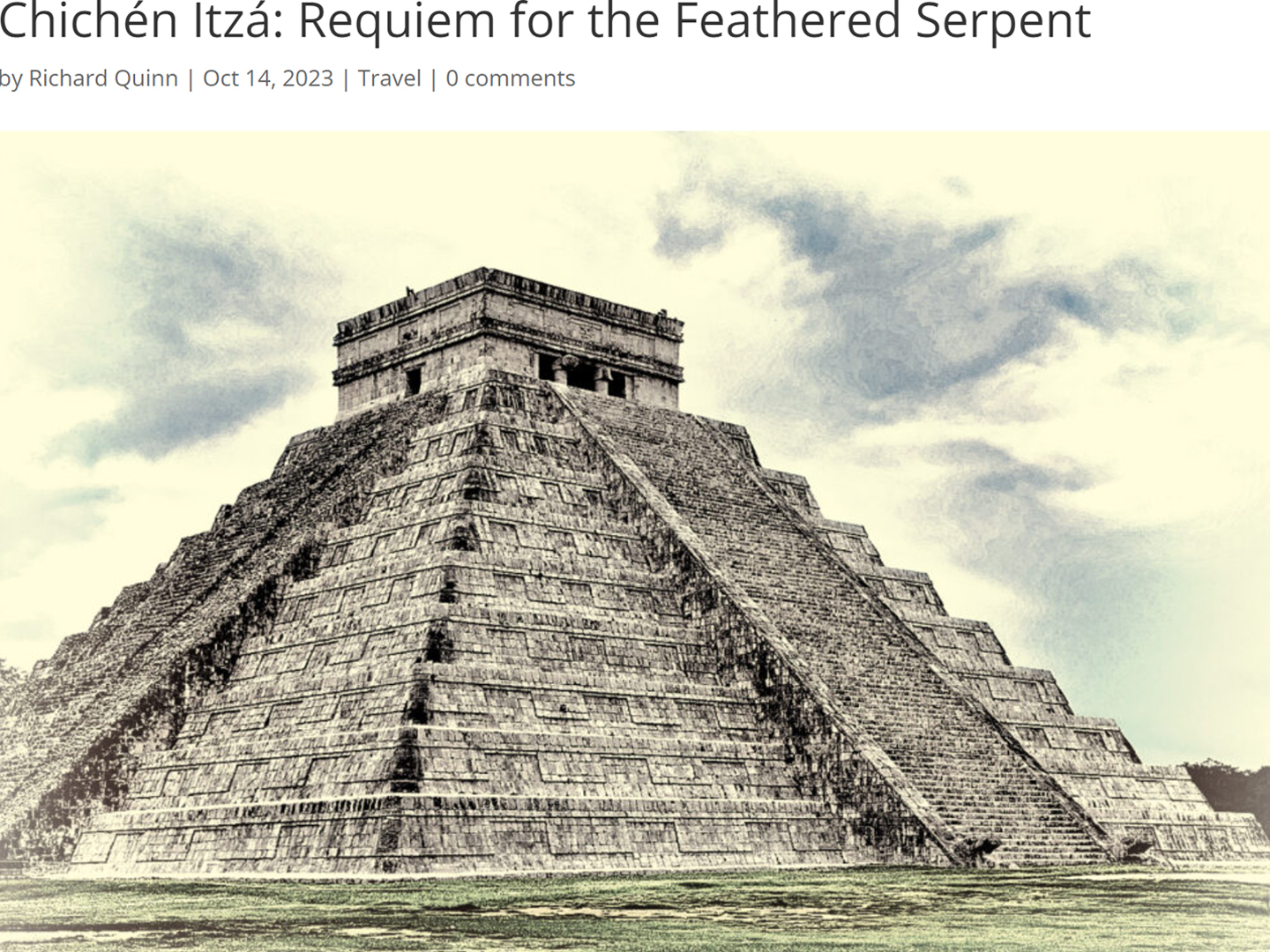

Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

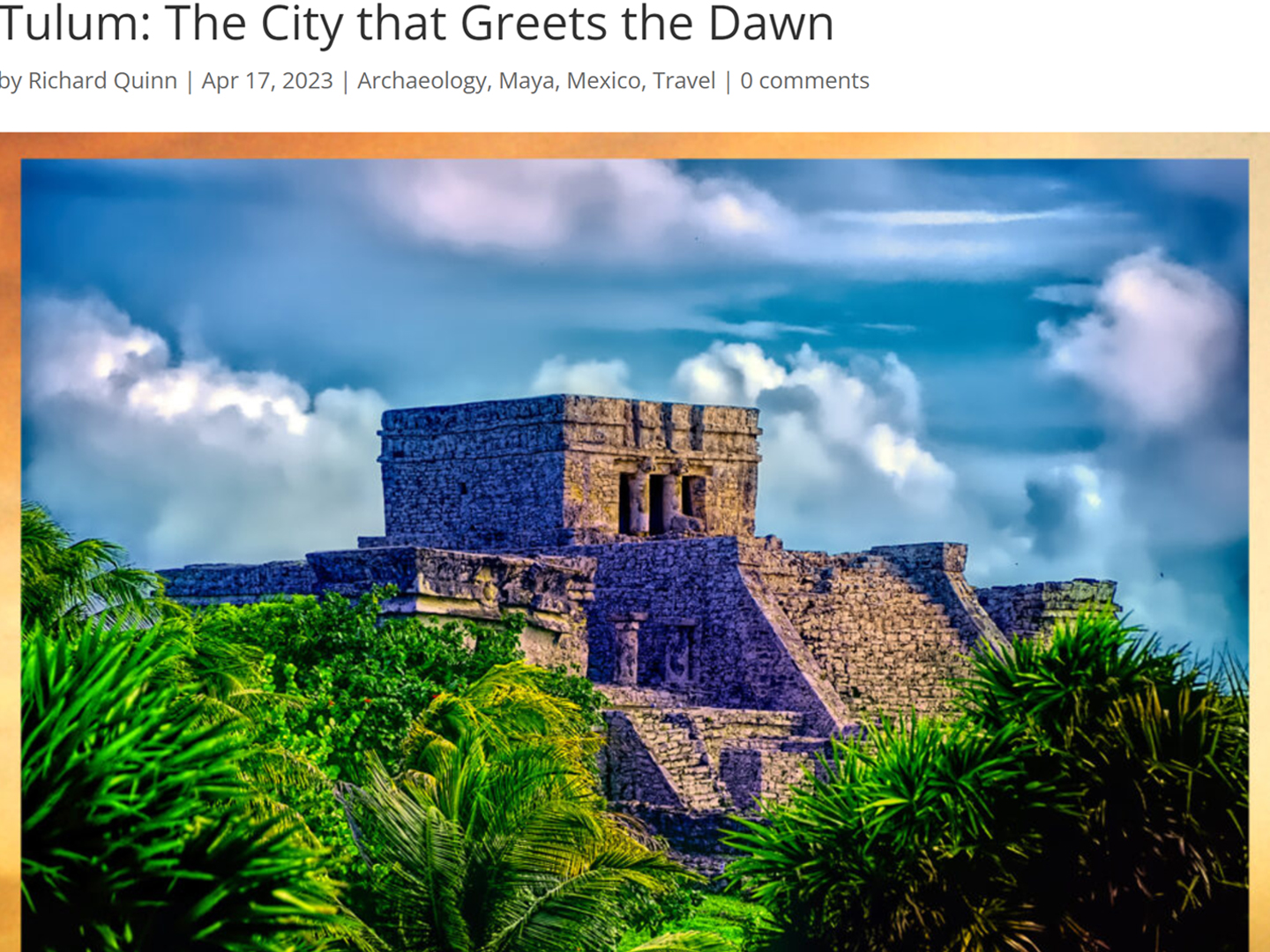

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

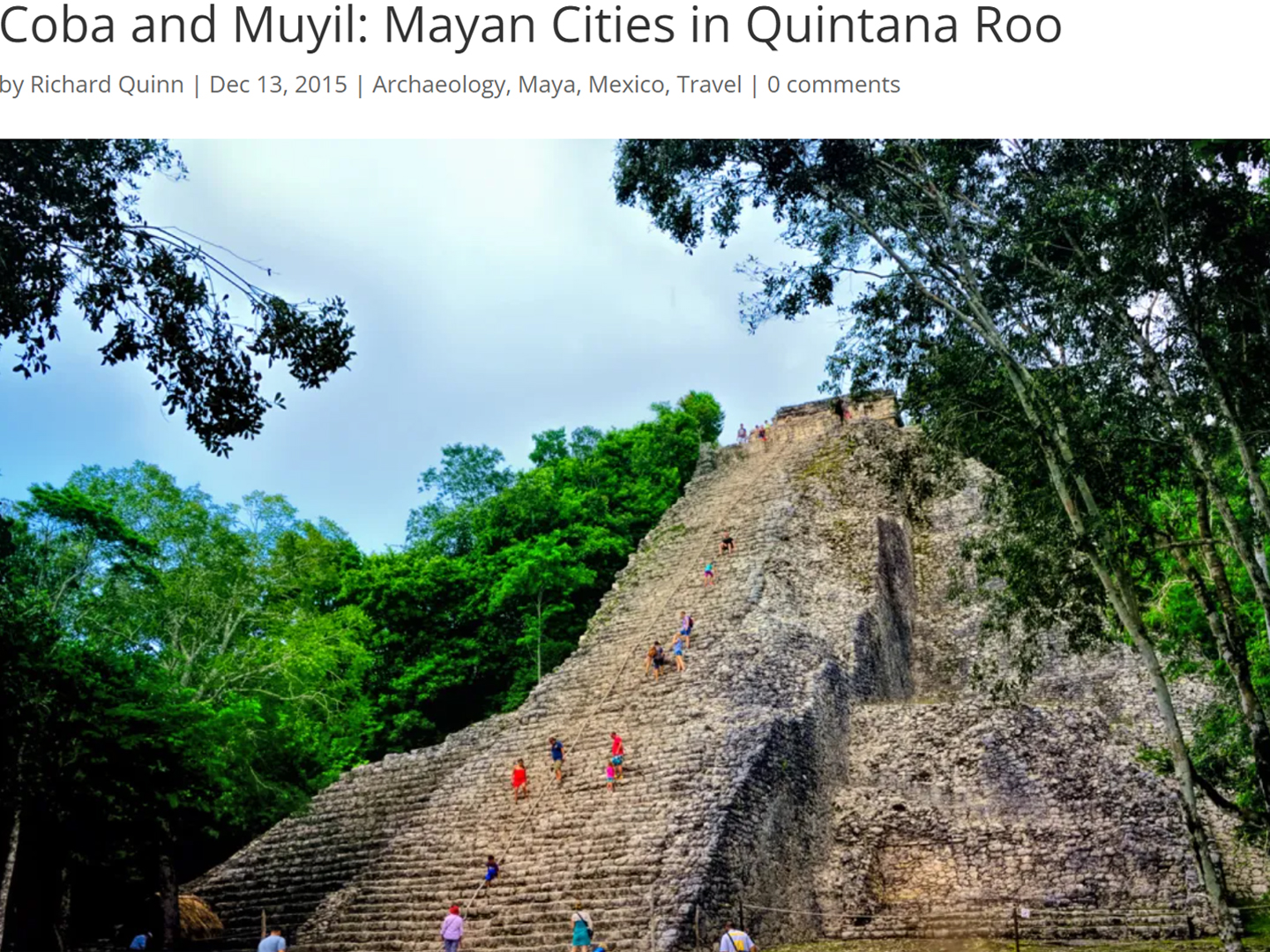

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

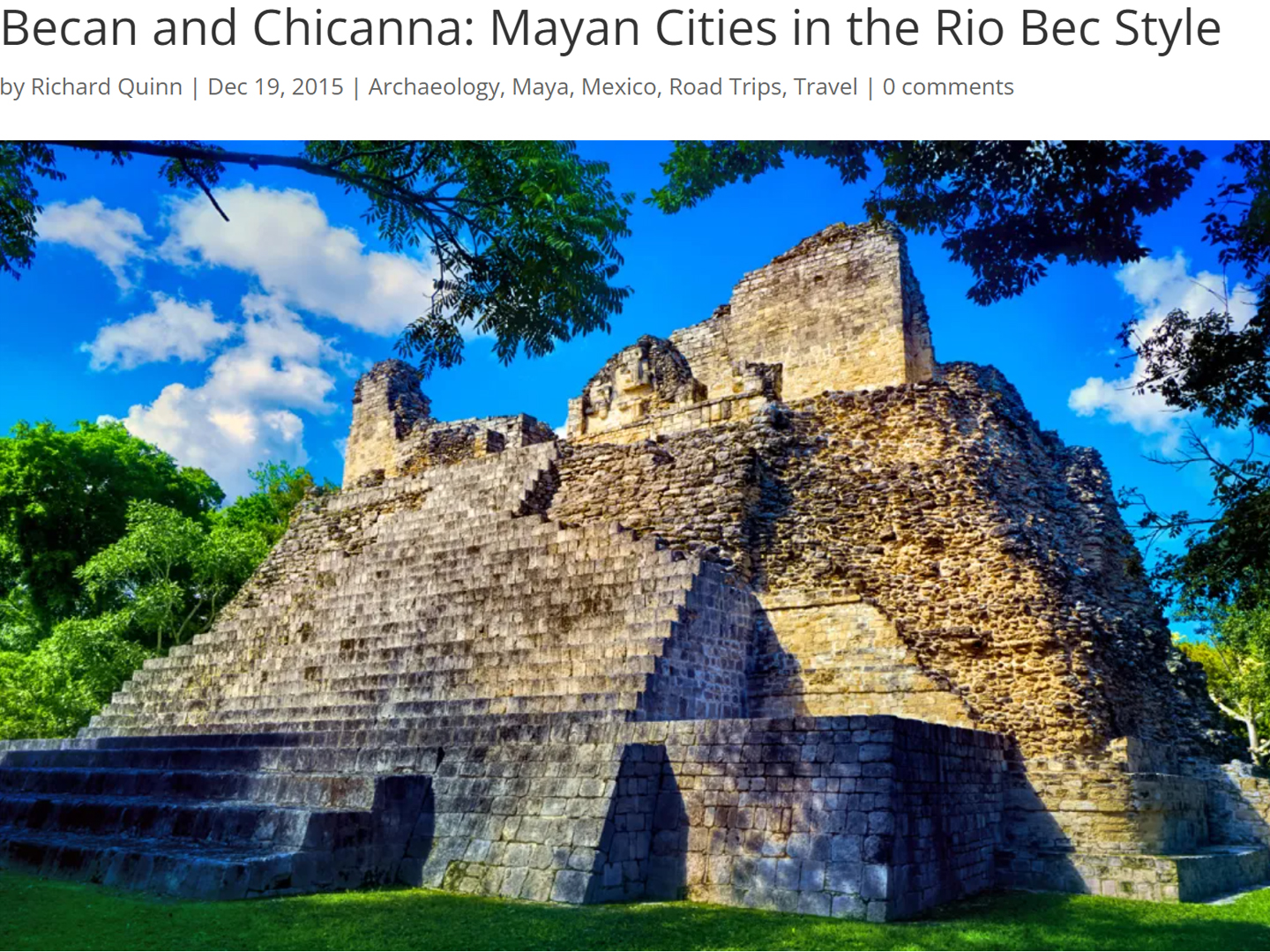

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

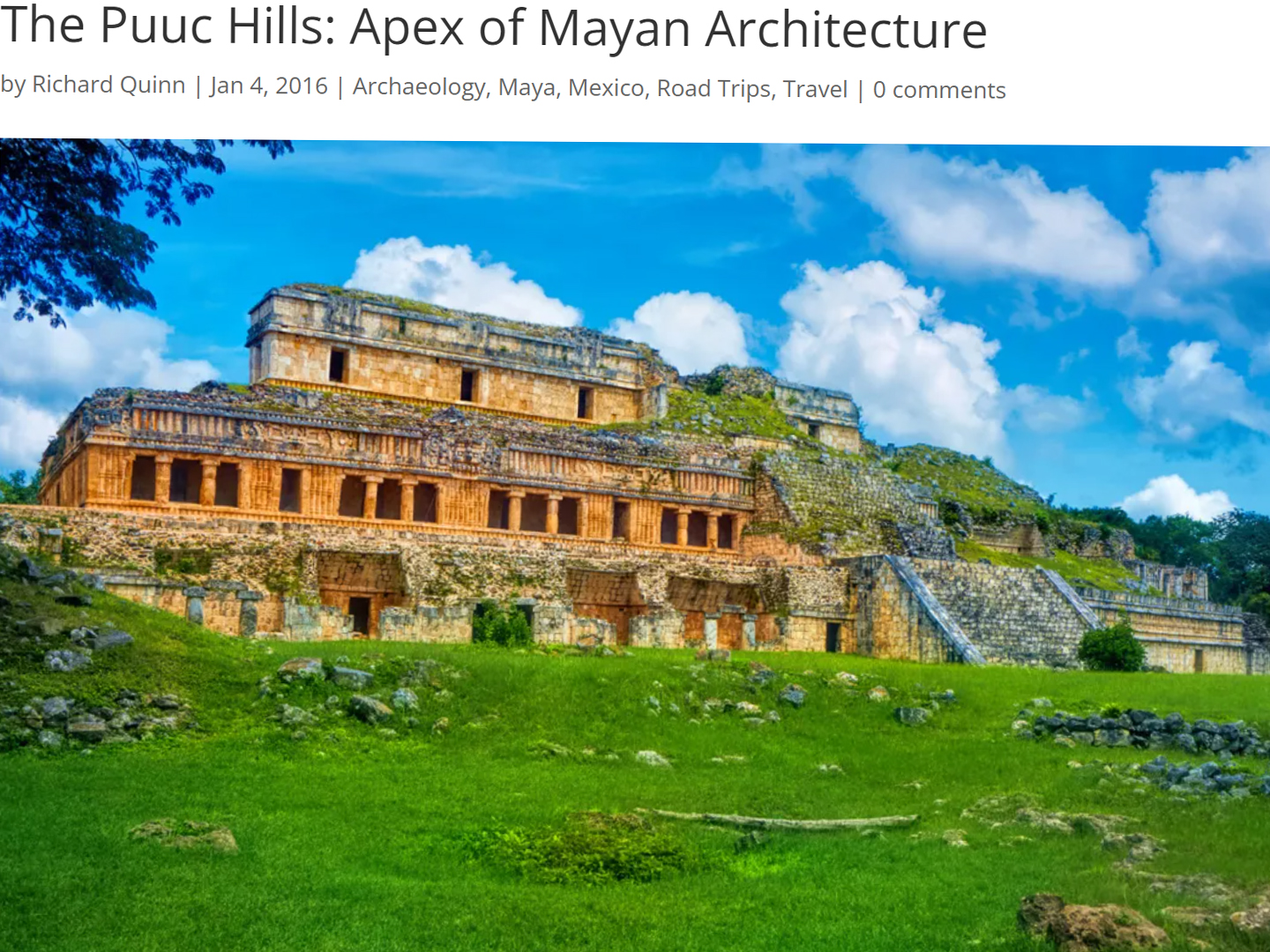

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. “Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins” was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after “Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali.” We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments