The Temple of Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent, is the largest structure in the ancient city of Chichén Itzá. Often referred to as the Castillo, it is perhaps the most perfect example of a Mayan step pyramid to have survived into our modern age, and it’s so well known, the mere suggestion of its shape has become an icon, the ultimate symbol of the Mayan culture that once dominated most of Central America. World-wide recognition was permanently assured when the Temple of Kukulkan was voted one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, alongside the likes of Machu Picchu, the Taj Mahal, and the Great Wall of China.

There’s just one small behind-the-scenes problem, something that bothers some people more than others. The perfect pyramid that you see today is a bit of a fabrication, a reconstruction of the original structure, created at the behest of the Mexican government, back in the 1920’s. The pyramid first built by the Mayans had been reduced to a crumbling pile of rubble, and they didn’t want to simply repair it, they wanted to improve it, in order to create an attraction with maximum appeal to tourists.

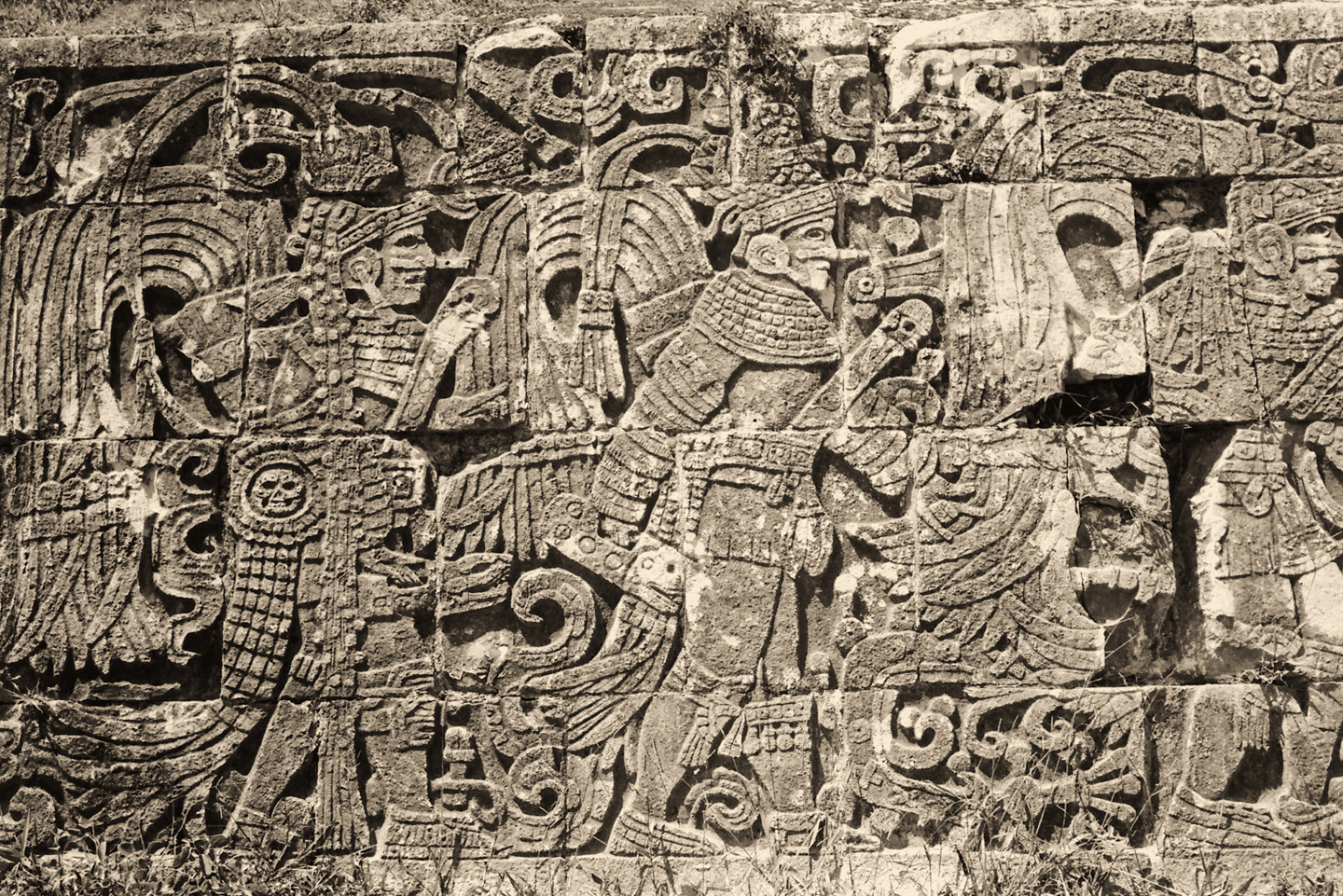

Carving at the base of the pyramid representing Kukulkan, also known as Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent

Computer and Tablet users: Click on photos to expand the images

To make it more aesthetically pleasing, they took significant liberties with the design, particularly with the decorative elements. Much of the original stone had been long since hauled away and used locally as building material, so they had to cut new limestone for the steps and balustrades, along with hundreds of newly cut flat slabs, which were used to create the facing that joins together so smoothly.

Two sides of the pyramid were finished to perfection, and that’s the face the Castillo shows to the world in 90% of the millions of photographs taken each year. The rest has been cleared and stabilized, but not reconstructed. What most visitors don’t realize is the extent to which the “finished” sides have been altered from the original, in design, materials, technique, and craftmanship. The “perfect symmetry” of the pyramid was significantly reinforced by skilled modern era stonemasons working from blueprints.

Two sides of the Castillo were reconstructed using newly cut stone

The other two sides are only partially finished

Several other structures were given the same sort of rebuild using newly cut stone, most notably the Temple of the Warriors and the Great Ball Court:

Temple of the Warriors

The Great Ceremonial Ball Court, largest ever found

These reconstruction efforts were quite successful, and the millions of tourists who visit the site every year are, for the most part, none the wiser. Chichén Itzá is widely praised for its remarkable state of preservation, never mind that so much of it isn’t really old.

The New Seven Wonder of the World was a poll sponsored by a Swiss foundation; Winners were announced in 2007

One question: if the Castillo is really just a modern reconstruction of a crumbling pile of rubble, why should it be considered a “Wonder of the World?” That would be because the winners of that competition were chosen, not by historians, but by internet users. Anyone with internet access was allowed to vote, and there were no restrictions on how many times you could vote. The methodology was so woefully unscientific that many countries boycotted the competition in protest, while others, like Mexico and Brazil, embraced it as an opportunity. Media campaigns were organized to get out the vote, and the response was big enough to propel the Castillo to an easy win. The real prize in the contest was tourist dollars. Calling the Castillo a “Wonder of the World” brings in more business than ever!

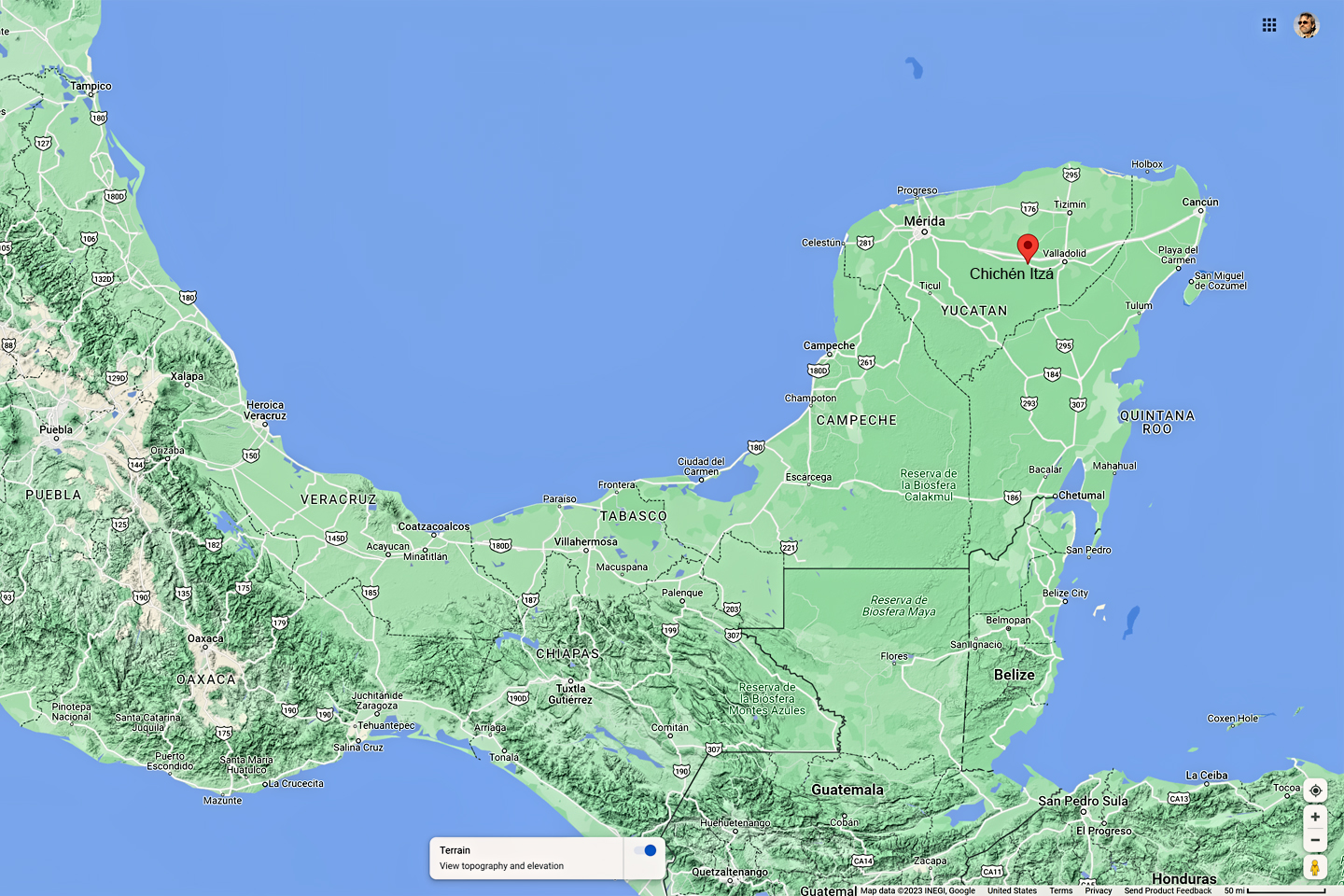

The ruined city of Chichén Itzá is a Mexican National Archaelogical Park, and since 1988, it has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Today, there are so many visitors, the infrastructure can barely accommodate them all. What started as a trickle, back in the mid-nineteenth century, turned into a flood when the Mexican government opened Cancún to development, back in the early 1970’s. The beautiful beaches draw international tourists by the millions, and Chichén Itzá, less than three hours away by bus, makes a perfect day trip to break up the monotony of a vacation spent lazing in the sun. Visitor numbers “A.C.” (After Cancún) increased more than tenfold, to as many as 8,000 people per day. Everything slowed during the pandemic, but at this point, the flood has returned, and shows no signs of abating.

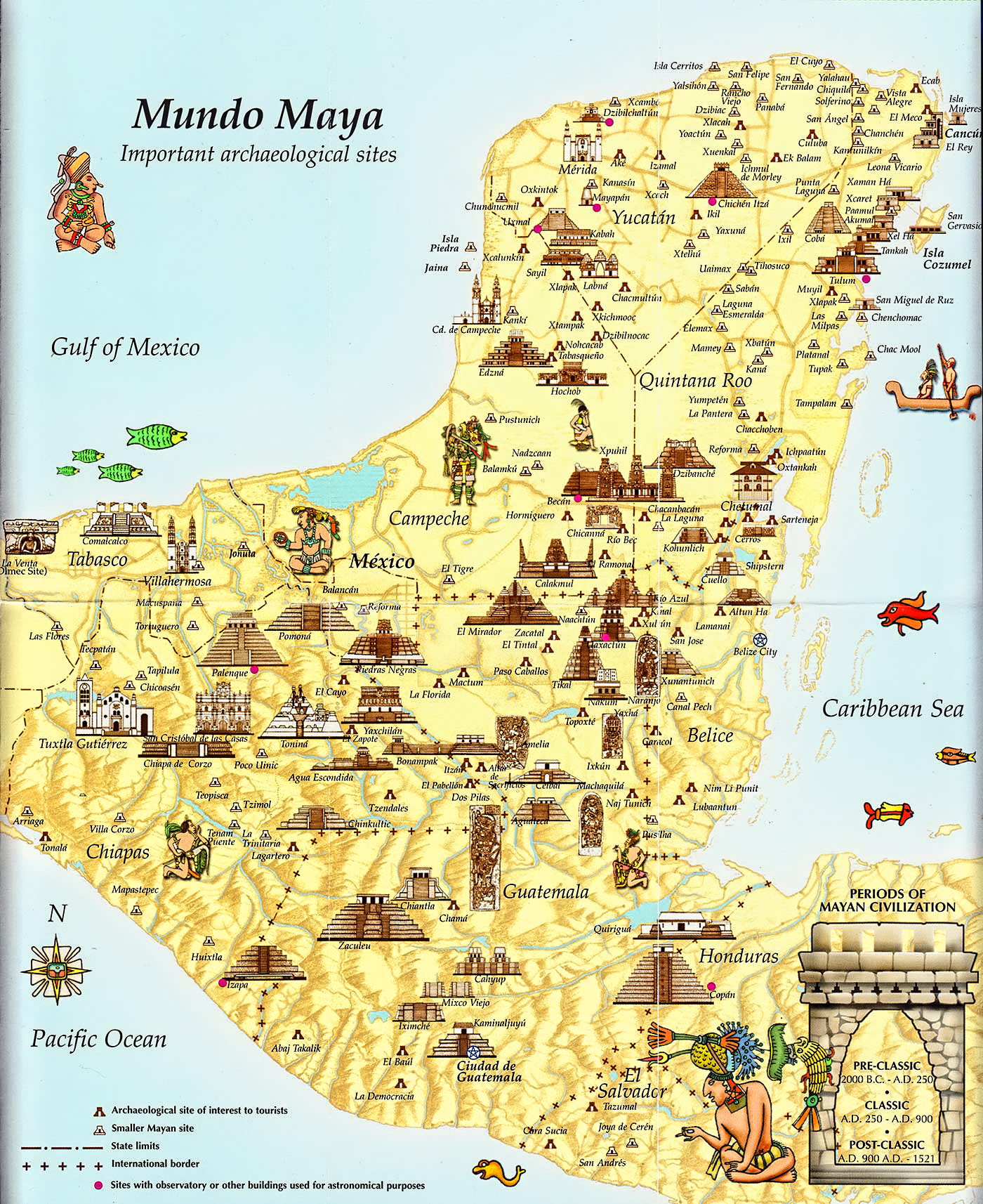

Mexico in general, and the Yucatan Peninsula in particular is rife with ancient ruins, many that are larger, more impressive, and more important historically than Chichén Itzá. As for the pyramid, there are so many of those danged things scattered throughout the region that it’s difficult to find an accurate count of them. Why, exactly, does the Temple of Kukulkan monopolize so much attention? Pretty simple, really: the lion’s share of the hype surrounding Chichén Itzá is a product of (brace yourself): highly effective marketing!

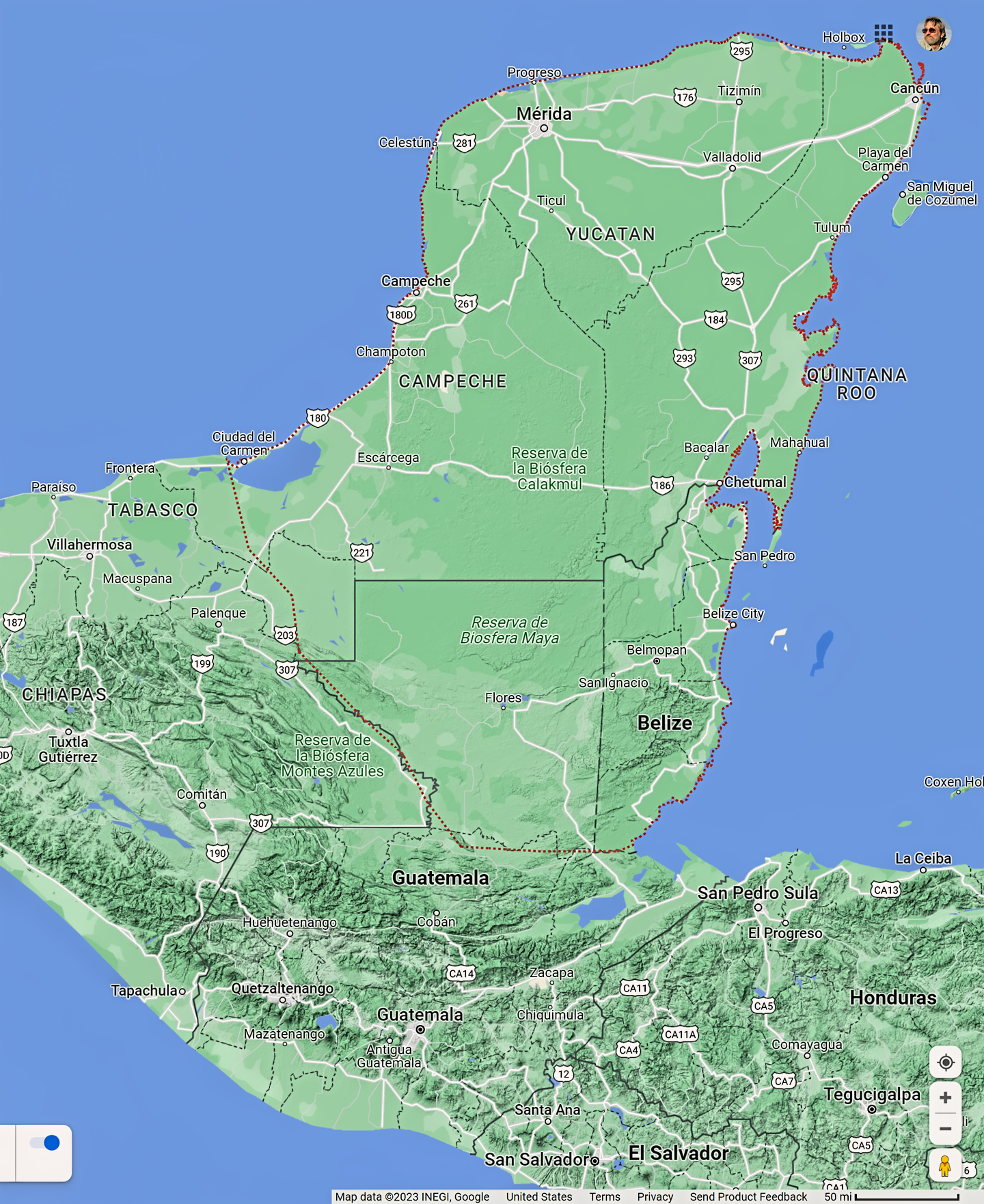

The location of Chichén Itzá and Cancun

Click for an expanded view of all maps and photos

Cancún was a planned city, built from scratch on a section of coast that was previously undeveloped. The goal of the project was to create jobs and a new flow of tourist revenue, but first, they had to attract outside capital, to create all the necessary infrastructure. Investors were leery of risking their money on an area nobody had ever heard of, so the Mexican government stepped up and provided financing for the first nine resort hotels. That got the ball rolling, but there were still no guarantees. The sparkling new venue had competition from every country that touches the Caribbean. They all had beautiful beaches, and they were all eager to attract free-spending tourists, so Cancún’s promoters realized they needed something that would give them an edge. What did their new Caribbean resort have that couldn’t be had just as easily in the Bahamas? Someone suggested Mayan ruins, so Advertising experts built a campaign around the idea. Travel agencies (anyone remember travel agencies?) put posters on display showing palm trees, beaches, and that perfect Mayan pyramid, the Castillo at Chichén Itzá. The rest, as they say, is history.

HISTORY OF CHICHÉN ITZÁ

When rain falls on the Yucatan Peninsula, it soaks through the thin soil into the porous limestone substrata, where it forms subterranean aquifers, connected by rivers that run entirely underground. Soft stone is eroded by flowing water, leaving hollow pockets below the surface, and when one of those pockets collapses, it creates a sinkhole. When the resulting depression is deep enough to reach the water table, it becomes a natural well, known locally as a Cenote.

Cenote Sagrado at Chichén Itzá

There is no other surface water in the Yucatan. No rivers, streams, lakes, or ponds, so the Cenotes were precious beyond measure to the ancient Maya, providing the only reliable source of the water required to sustain communities with populations that often numbered in the thousands. The most powerful clans controlled access to the wells, one of many ways that the upper class of Mayan society dominated the lives of the common people.

The settlement that ultimately became Chichén Itzá was established in the vicinity of five cenotes, one of which was later buried beneath the massive bulk of the Castillo. The largest of those natural wells, the Cenote Sagrado, pictured above, was considered a sacred portal to the underworld, and as such, was frequently used as a receptacle for sacrificial offerings, including human sacrifice. This was confirmed when land owner Edward Thompson dredged the cenote, early in the 20th centry, and recovered human remains from the muck at the bottom, along with precious artifacts made of gold and jade. The importance of the Cenote is underscored by the name of the city, Chichén Itzá, which means, “at the mouth of the well of the Itzá.”

Map of the Mayan World: © Uncovered History.com

The Maya were never a single unified cultural entity. There were dozens, if not hundreds of different ethnic divisions, ranging in size from isolated clans with a few dozen members to sprawling cities with tens of thousands of citizens. There were scores of different Mayan dialects, countless unique oral traditions, and endless variations in the style and pattern of dress. The common element that most directly bound them as a people was their religion, an animistic belief system that deified every important aspect of their environment, while holding their kings, nobles, and priests above the level of the common man, more closely akin to the gods, to be worshipped, as well as obeyed.

The Itzá were one of the most prominent of those many ethnic groups, with roots in the Peten region of Guatemala, dating back thousands of years. When their population grew too large in the south, a number of them migrated north into the Yucatan, where they established the city of Edzná, (First House of the Itzás). Several hundred years later, they spread even further north, to the city beside the sacred well. The city that still bears their name.

Mayan Archaeological sites © ChichenItza.com

Map of the Yucatan Peninsula ©Google.com

The earliest version of Chichén Itzá was founded in the mid-fifth century, around 450 A.D., during what’s considered the Early Classic period of Mayan history. During that era, the largest, most significant Mayan centers, such as Tikal and Palenque, were all in the southern highlands, so the newer communities in the Yucatan were almost like outposts on the frontier, important as trading hubs, but not particularly powerful.

In the middle of the 9th century, there was a mysterious collapse of the socio/political structure in those southern kingdoms, leading to the abandonment of many the most populous Mayan cities, including Chichén Itzá. The most probable culprit was climate change, in the form of an extended drought that would have made it impossible to raise enough food to sustain so many people in one spot. There would have been famine, and many would have starved, while the survivors broke up into smaller bands, spread out across a wider area. A hundred years later, around 950 A.D., the drought had ended, but the southern kingdoms were slow to recover. Another group of Itzá from the Peten migrated into the lowlands, and when they reached the northern Yucatan, they claimed the city by the sacred well as their own.

There is some disagreement among scholars as to exactly what happened next, the timing and the sequence of events, but it was around this time that a contingent of Toltecs from Central Mexico, ostensibly led by their King, Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, invaded the Yucatan, and placed themselves in charge.

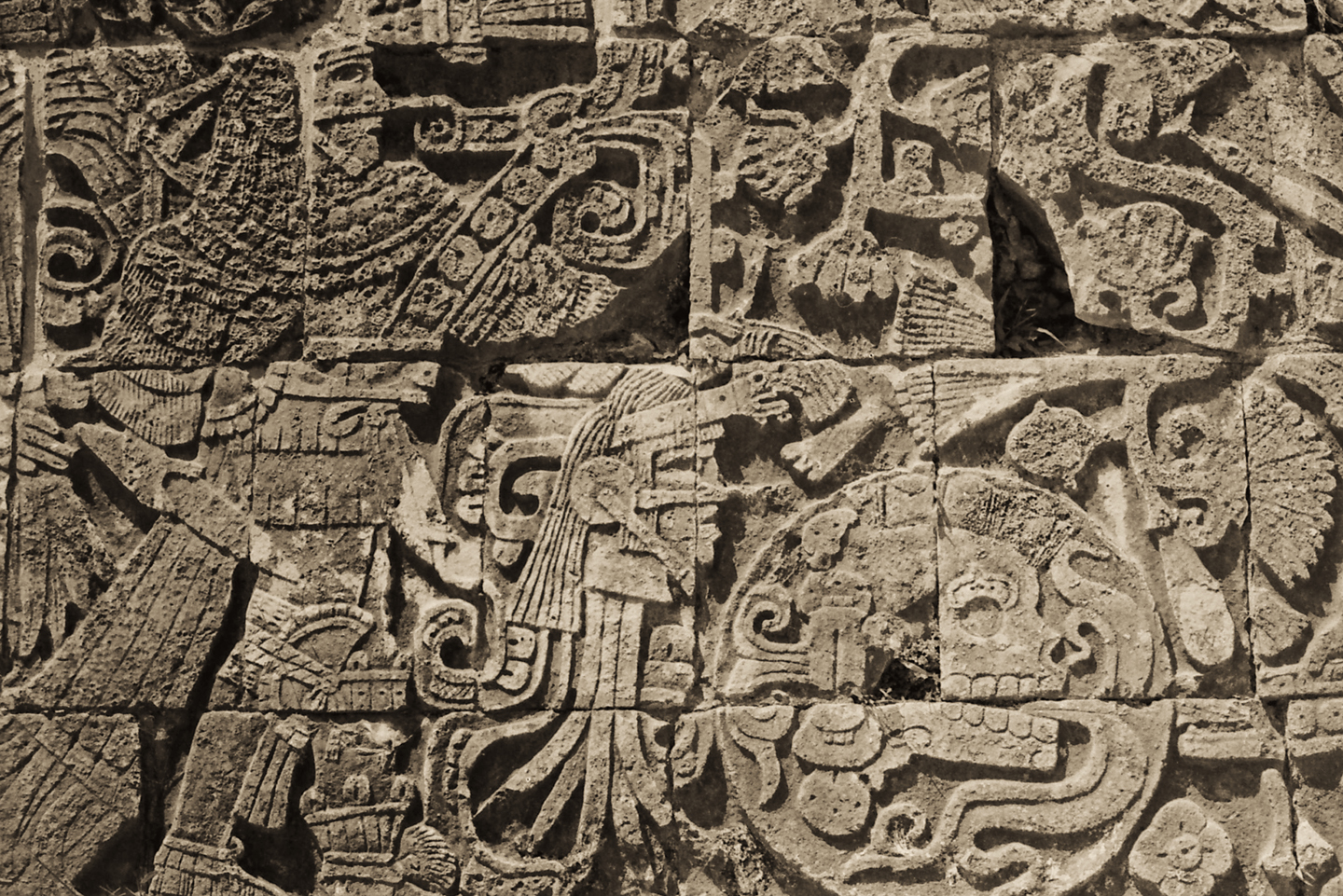

Over the next 300 years, from 950 AD to 1250 AD, there was a flurry of new monument building at Chichén Itzá, and this time around, the Feathered Serpent was the dominant theme. Quetzalcoatl was not merely the king, but the patron deity of the Toltecs, who brought along with them the bloody cult of human sacrifice that predominated in the highlands of Central Mexico. Their grisly obsession was even reflected in the architecture. Chiseled reliefs on monumental platforms featured gruesome death’s heads, and fanged serpents carved from stone guarded the steps and crowned the balustrades of the pyramids.

The largest monument of all, the pyramid we call the Castillo, was entirely dedicated to the fearsome Feathered Serpent, known as Kukulkan in the Mayan tongue.

The primary focus of these Post-Classic Maya was war. Neighbor fought neighbor, king against king, in battles waged for the express purpose of taking captives. The captives provided the slave labor required for the building of pyramids, and they also provided a steady supply of the sacrificial victims required by the Feathered Serpent and his bloodthirsty priesthood.

Chichén Itzá was the dominant force in the Yucatan for at least 100 years. They formed a military alliance with the cities of Mayapan and Uxmal, and remained at the head of it, but only until the rulers of Mayapan tired of the arrangement, and rebeled against them. Mayapan conquered Chichén Itzá, and replaced them as leaders of the coalition, known to history as the League of Mayapan. The cycle of conquest and the taking of captives continued, but war and the building of stone monuments are hugely expensive endeavors that eventually became unsupportable, so monumental construction ceased after the 13th century. The flow of human blood required to slake the thirst of the mighty Feathered Serpent slowed to nothing, and the great cities of the Yucatan went into decline.

By the time the Europeans arrived in the area, early in the 16th century, most of the population had abandoned the elaborate, high maintenance ceremonial centers, in favor of a simple existence as subsistence farmers, living in scattered villages and homesteads. Exposure to the old-world diseases brought from Europe on the Spanish ships decimated what was left of the Mayan population, and the stratified social structure of of modern Mexico, rigidly biased against native cultures, has kept them repressed. The Maya are a resilient, and very patient people, with roots in their homeland dating back thousands of years. Who’s to say that they’ll never rise again?

ZAPATISTAS: 21st CENTURY MAYA

In the forested hills of Chiapas (well south of Chichén Itzá), descendants of the Maya make up most of the population, but extreme poverty makes their lives extremely difficult. The Zapatista Movement, a coalition of indigenous political activists, encourages protests that block highways. They’ll deliberately stall commerce for days at a stretch, for the purpose of calling attention to their demands. According to this sign posted on the highway (see below), they want the government to put a stop to arms trafficking, to drug trafficking, and to illegal logging that destroys their natural environment. They control the main roads in the State of Chiapas, and they don’t hesitate to leverage that fact to press their cause.

Sign erected by the Zapatistas, marking the boundary of their territory in Chiapas, and listing their grievances. “In rebellion: Here, the people rule, and the government obeys.”

Descendants of the Maya live traditional lives in the forested hills of Chiapas, birthplace of the Zapatista movement

Zapatista Road Block near Palenque, stopping all traffic on major highways to call attention to their issues

Horses are still a common mode of transportation in the rural segments of Chiapas, Zapatista territory.

Visiting Chichén Itzá today is the easiest thing in the world. The ruins are located less than three hours west of Mexico’s popular Caribbean resorts in Cancun and the Riviera Maya, and even less distance east of Meridá, the capital of the Yucatan, and its most populous modern day city. Using any of those locations as a base, there are dozens of comfortable, air conditioned tour buses hauling visitors to and from the archaeological park every day of the year, mostly day trips that allow three to four hours exploring the ruins, with or without a guide. For a more relaxed experience, there are numerous hotels in the immediate area, which make it easy to spread your visit across more than one day, and avoid the busiest time periods.

A tip for photographers: Try to get to the park just as it opens at 8 AM. That’s when you’ll have the best light, and the smallest likelihood of crowds. The easiest way to get there early is to stay the night before in the nearby town of Piste. Check out my earlier post: Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

If bus tours aren’t your thing, it’s simple enough to rent a car and drive yourself to Chichén Itzá. Starting from Meridá, MX 180 runs due east to the ruins. The highway splits at the small town of Kantunil, offering a choice of MX 180 and MX 180D. The “D” indicates a Cuota, or toll road, an alternative to the “libre” (free) State Highways. In Mexico, it’s almost always better to choose the toll roads, which are better maintained, less congested, and significantly faster than the state roads, which pass through the center of every small town along the way. Coming from Cancun, you’ll take MX 180D for the whole distance of 200 km, a drive that takes about 2.5 hours. It’s a largely rural area, so traffic is never a problem.

Click for an expanded view of all maps and photos

EXPLORING THE RUINS

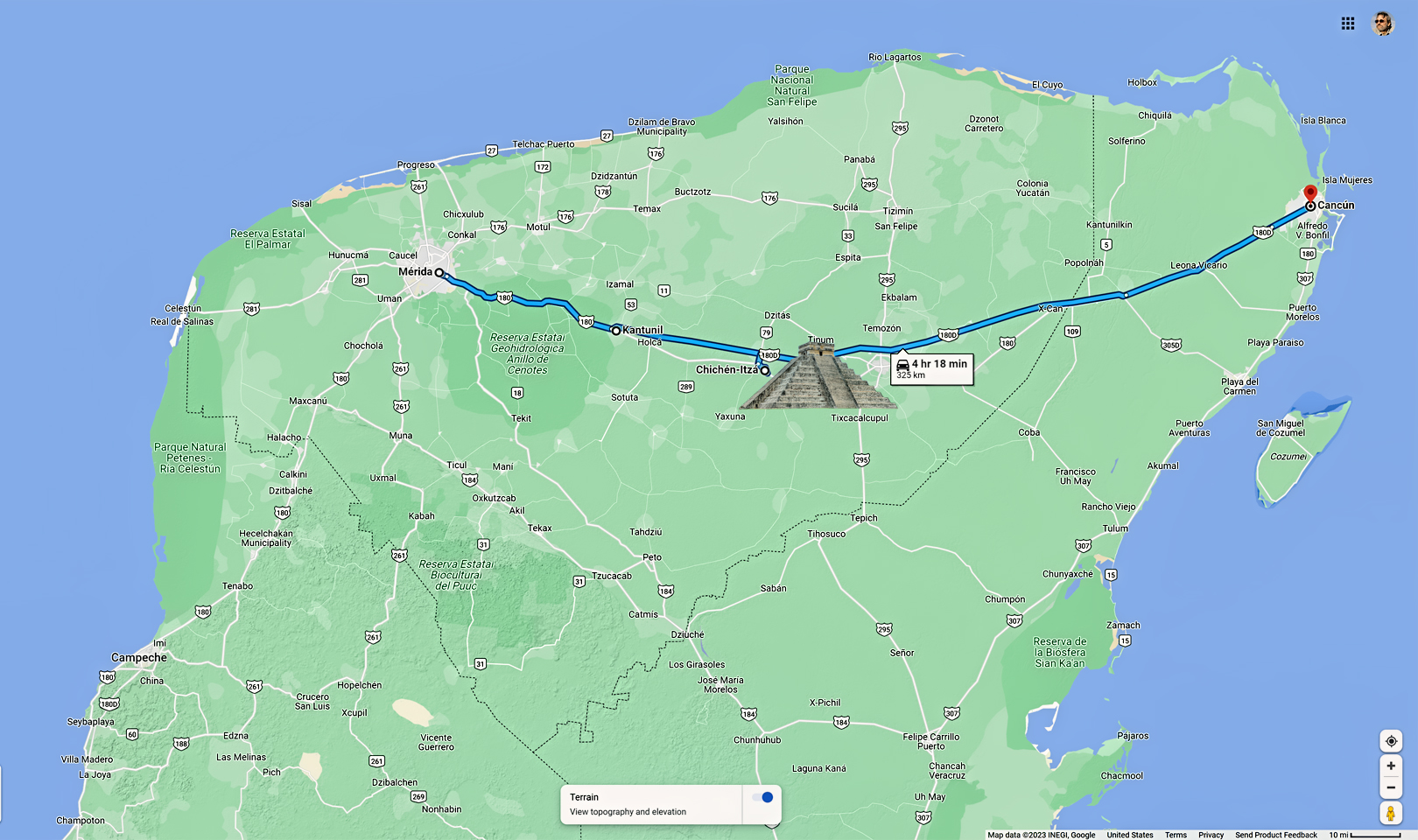

The Chichén Itzá Archeaological Park as it exists today.

THE CASTILLO

Chichén Itzá is by far the most commercialized of all the Mayan ruins in Mexico, but some might find that an advantage. By the main tourist entrance there is a snack bar, rest rooms, and souvenir shops, along with vendors hawking merchandise of every description. The smart tourists save all that until last. The not-so-smart folk head there first, and they spend half their time at the ruins standing in line at the concessions. The first thing you’ll see after you leave the crowded entrance and enter the park itself is the Big One: the Castillo, the Temple of Kukalkan.

The Castillo at mid-day in mid-October, nominally the “off” season

The Castillo at 8 AM, when the park first opens, before the tour buses arrive

The perfect Mayan pyramid, the Wonder of the World, looks exactly like every photograph you’ve ever seen of it: Nine tiers topped by a stone temple, rising almost 100 feet from its base, with huge stone staircases climbing each of the four sides. If you’re there during the day, especially in peak season, there will be people everywhere in this section of the park. That’s good for providing a sense of scale, tiny tourists with the massive pyramid in the background, but it does tend to spoil the whole “Indiana Jones” ambience. If you’d like to see Chichén Itzá without the crowds, get there when they first open!

Many of the largest structures in the Mayan cities were built atop older buildings, and the Temple of Kukulkan is no exception. Excavations sponsored by the Mexican government back in the 1930’s revealed a staircase below the north side of the pyramid, which led to the discovery of a smaller, older temple beneath the big one. Inside the smaller temple was a hidden chamber containing a Chacmool statue, along with a throne in the shape of a jaguar, painted red, with jade inlays representing the spots. The remarkable chamber was open to the public until 2006, and until 2008, tourists were still allowed to climb the pyramid, which they did, in great numbers. At any given moment, there were steady streams of people moving up and down, everyone eager to check out the view from the top. All of that changed when an elderly woman from the U.S. slipped and fell down the steep staircase to her death. Today, everything is roped off, out of concern for damage to the structures, as well as visitor safety.

The Maya were keen observers of the heavens, and many of their monumental structures, including the Castillo, were positioned to align with specific celestial events. There is a well-known phenomenon that occurs every spring during the equinox, and attracts a larger than usual crowd to Chichén Itzá. When viewed from a certain angle, the steps of the pyramid cast a zig-zag pattern on the balustrade of the main staircase, terminating at the carved serpent’s head at the base of the pyramid. The pattern of light and shadow appears to “climb” the temple and is thought to represent the feathered serpent, Kukulkan. It is widely believed that the Maya positioned the pyramid precisely in order to create this effect, timed for the equinox.

Serpent of light and Shadow © Public Domain

Studies have shown, however, that the effect is visible on a number of different days, before and after the actual equinox, so it could not have been used to pinpoint the date with any precision. (That, plus the fact that the whole south face of the pyramid was rebuilt using new stone, less than a hundred years ago.) Believers will always believe, and the crowds will continue to show up every spring, but in all likelihood, the whole business is nothing more than a well-timed coincidence.

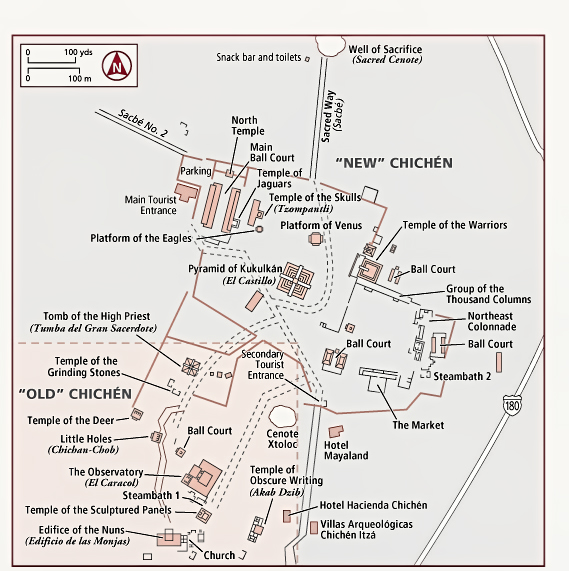

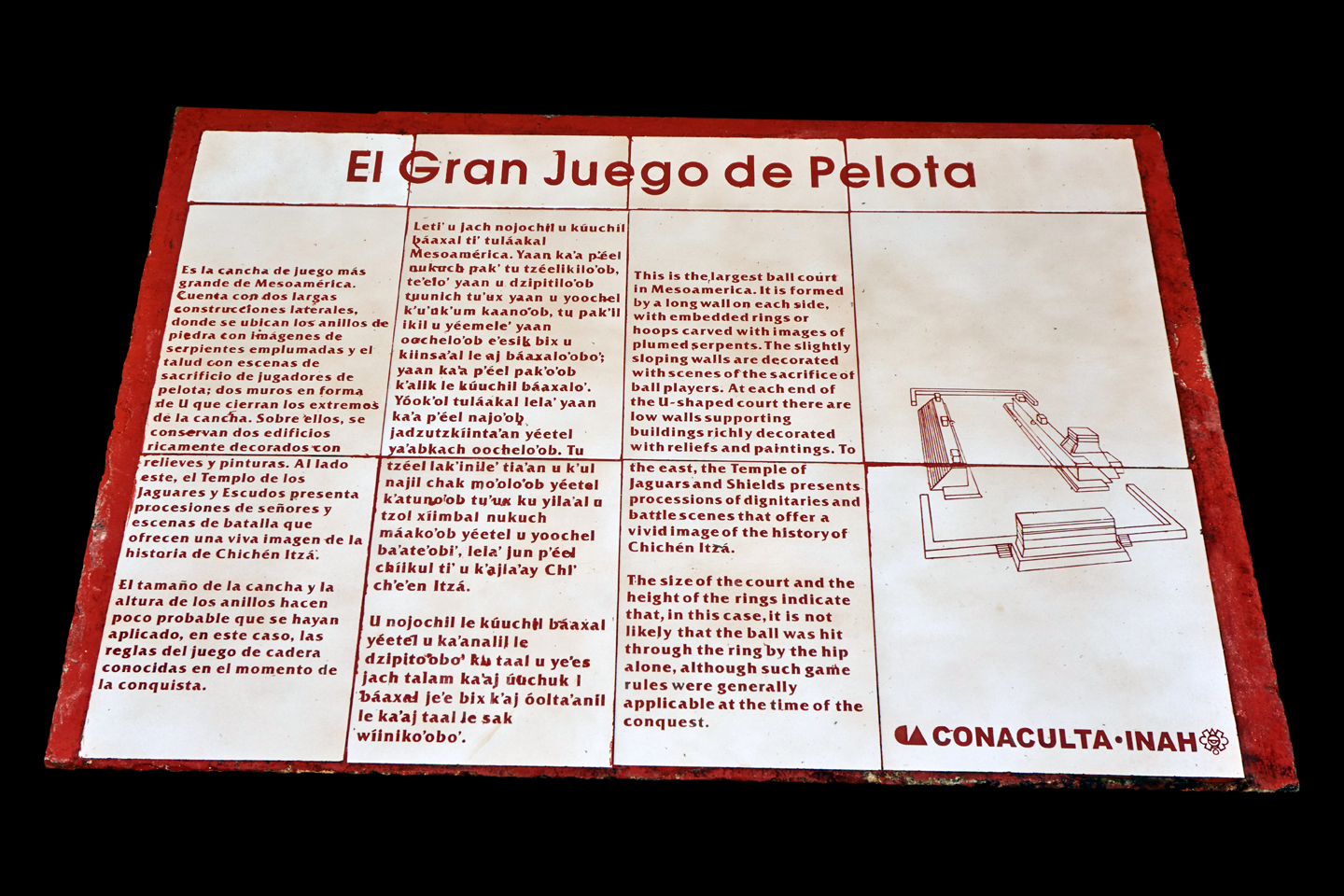

THE GREAT BALL COURT

As you walk toward the Castillo from the main entrance, you’ll see the Great Ball Court on your left. Every important Mayan city had one of these, a court for playing a ceremonial ball game, but this stone-walled playing field at Chichén Itzá is the largest that’s ever been found. Opposing teams attempted to knock a large, hard rubber ball through goal rings mounted high on the smooth walls, using only their hips and elbows. The game, played between rival factions or rival cities, was deadly serious, as the losers were generally sacrificed at the end of play!

The Ball Court at mid-day in October

The Ball Court at 8 AM, when the park first opens

A sign in Spanish and in English explaining the Ball Game

Spectators would view the game from above, standing along the tops of the walls, cheering on their favorites. Important personages occupied “box seats” at the corners and at the end of the court.

The goal rings at Chichén Itzá were mounted 30 feet up on the sheer walls, and the hole wasn’t much larger than the ball would have been, so an actual goal in this venue would have been tough!

Carved reliefs along the base of the walls commemorate important victories. Players are shown wearing the leather armor that protected them from being injured by the heavy rubber ball.

TEMPLE OF THE SKULLS

When warriors from the Toltec kingdoms in the highlands of central Mexico invaded the Yucatan in the 10th century, they introduced the practice of human sacrifice. Captives taken in battle were grist for the grisly mill, splayed on altars at the tops of the pyramids, their still beating hearts cut from their chests and offered to Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent. In exchange for copious amounts of blood, there was a promise of rain, bountiful harvests, and victory over the city’s enemies. The human skull became a decorative motif, celebrating the concept of death by sacrifice. Also known as the Tzompantli, this platform adjacent to the Ball Court features hundreds of carved craniums.

Tzompantli: Temple of the Skulls

PLATFORM OF VENUS

Moving east from the Tzompantli, you’ll come to the Platform of Venus, located between the Castillo and the Sacred Cenote. This is a temple that was dedicated to the planet Venus. Observation of the planets and other celestial bodies enabled accurate prediction of important events, such as solstices, facilitating proper scheduling of the planting and harvesting of food crops. Such knowledge was an important source of power for the Mayan priesthood.

The Platform of Venus, decorated with serpent heads and hieroglyphic carvings

TEMPLE OF THE WARRIORS

Just beyond the Platform of Venus, on the east side of the main plaza, the second largest building at Chichén Itzá dominates your view. Known as the Temple of the Warriors, it is a large stepped pyramid, topped by shaped pillars and a statue of a reclining Chacmool. In front of the pyramid, alongside it, and to the rear, the structure is surrounded by free standing pillars said to represent Mayan Warriors. This configuration is quite similar to one of the temples at Tula, the Toltec capital in Central Mexico, and is considered further evidence of the undeniable connection between the two cultures.

Several views of the Temple of the Warriors. The sepia tone “long shot” (above) was taken from atop the Castillo in 1970; original photograph © Carl Duisberg. (Note that this viewpoint is no longer accessible to the public!)

GROUP OF A THOUSAND COLUMNS

The pillars that surrround the Temple of the Warriors are referred to as the Group of a Thousand Columns. By actual count, there are only about two hundred columns here, but let’s face it: “Group of a Thousand Columns” sounds much more majestic than a mere “Group of Two Hundred Columns,” and the Spanish Colonists who were the first to explore these ruins were notoriously fanciful when it came to the names they applied to the old Mayan structures.

The pillars grouped along the south wall feature carvings of warriors in bas relief. It is those carvings that inspired the name of the Temple of the Warriors. (Photo at right/below © Carl Duisberg). When in use, the rows of columns are believed to have supported the roof of a large building, possibly a meeting hall, though it’s function undoubtedly varied over time. The roof featured a Puuc style mosaic frieze with numerous masks of the big nosed rain god, Chac. Sadly, the building and it’s roof, along with the frieze, have long since completely collapsed, and the debris has been cleared away, leaving nothing but the mysterious thousand (make that two hundred!) columns, neatly lined up in rows.

The Group of a Thousand Columns

TOMB OF THE HIGH PRIEST

Sometimes called the Ossuary, this seven-tier step pyramid was first excavated by Edward Thompson, who was, at one time, the owner of the land on which the ruins of Chichén Itzá are located. Thompson discovered several sets of skeletal remains inside a cave at the center of the pyramid, and for that (and no other) reason he called the structure the “Tomb of the High Priest.” Later studies concluded that the pyramid was not actually a tomb, and there was no evidence that the individuals whose remains were found beneath it had ever been priests. Thompson’s name for the structure seems to have stuck, despite those findings. Regardless of what you call it, it’s a marvelous monument, featuring carved serpent heads at the base of the steps, like a smaller version of the Castillo.

Moving on from the Tomb of the High Priest, you enter what’s known as “Old Chichén,” where some of the oldest, most interesting buildings in the city are located.

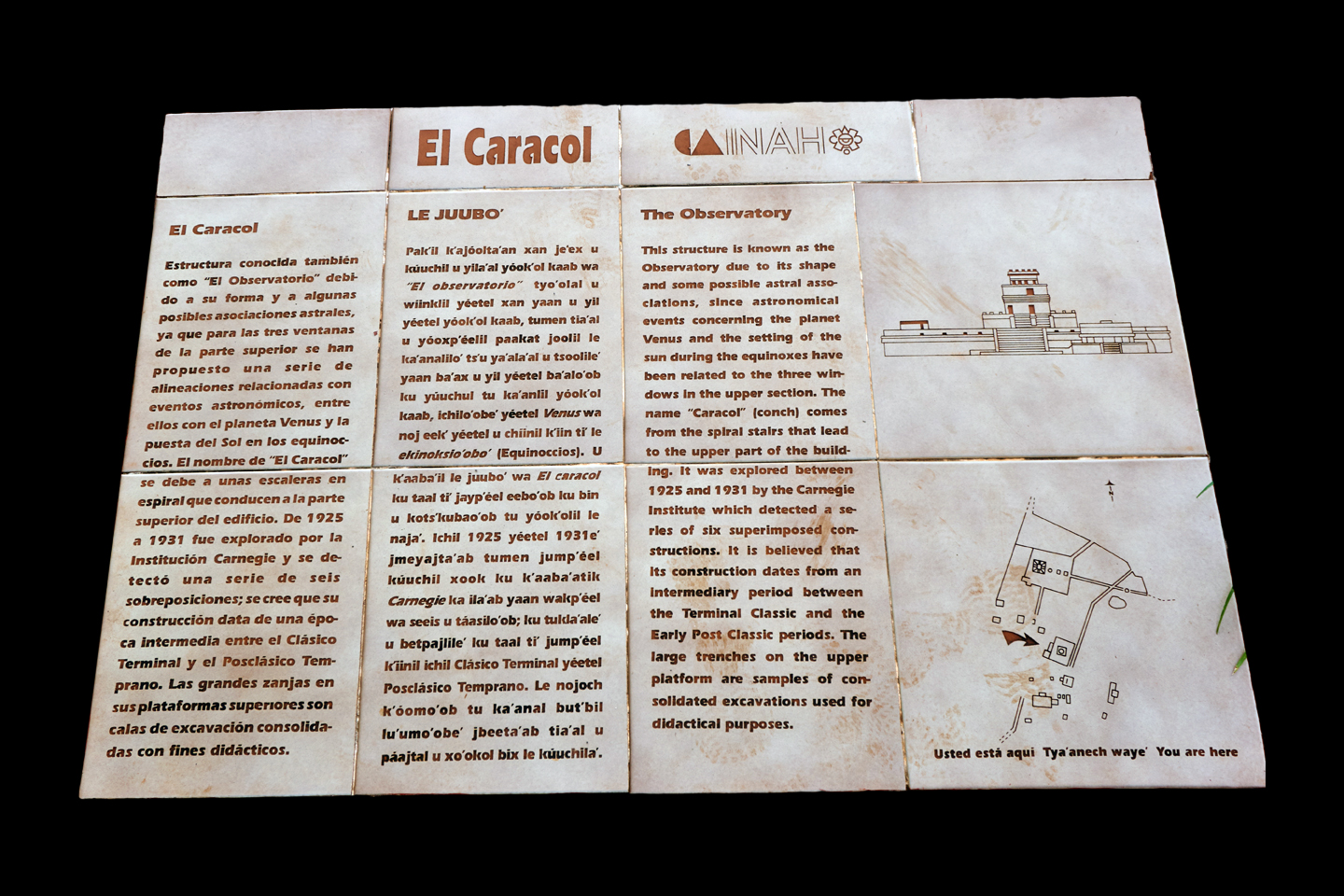

CARACOL (THE OBSERVATORY)

The largest monument in Old Chichén is an unusual structure that’s believed to have been used as an observatory. There is a multi-level round tower atop a large square platform, with doors and windows positioned to align with the the planet Venus on certain important dates. There is a spiral staircase inside the tower that has given rise to the building’s popular name, El Caracol, the Snail (or Conch); a reference to the spiralling chamber inside a shell.

LA IGLESIA (THE CHURCH)

Carving of a Mayan deity above the main doorway of the Iglesia

Mayan cities were built over long spans of time, spans measured in hundreds, if not thousands of years, and they tend to feature a range of different architectural styles. Nowhere is this more apparent than at Chichén Itzá. The Toltec influence on some of the best known structures is inescapable, pyramids with extra broad staircases being the most obvious examples, but in the section of the park known as “old Chichén,” there is a group of buildings that is very obviously different. These structures feature elaborate friezes on the outer walls, and on a cornice that wraps around the upper section of each building, just below the roof. The friezes are mosaic art, assembled from cut stone that forms fascinating geometric patterns, including numerous depictions of Chac, the rain god, with his prominent hooked nose.

These heavily decorated buildings were constructed in what’s known as the Puuc Architectural Style, which had its origins in the Puuc Hills of the southwestern Yucatan. Uxmal, at one time a rival to Chichén Itzá, showcases the most elaborate examples of Puuc Architecture, but these buildings in old Chichén most certainly have their merits.

The first is a rectangular temple known as the Iglesia, the church. Early Spanish colonists, first to explore the ruins, assumed that this whole group of buildings had a religious function. They thought the larger structure was a residence for nuns and that this free standing smaller building must be a church.

Several views of the Iglesia, with closeups of the mosaic frieze, highlighting numerous depictions of big-nosed Chac

THE NUN’S HOUSE

Alongside the Iglesia there are two more Puuc style buildings. Taken together, they are known as the Nun’s House, or the Nunnery, so called because there are small rooms in the interior of the structures that early Spanish explorers likened to Nun’s cells in a convent. The back side of the largest building features a wall some two stories in height. When in use, all of these buildings would have been stuccoed and painted, a scene that would have been strikingy different from what you see today.

CHAC

In the dryest parts of the Yucatan Peninsula, the Maya depended almost entirely on rain water, which they collected, very efficienty, and stored in large underground cisterns. To insure adequate rainfall, they venerated a god they called Chac, and they adorned every important building with his image. His toothy grimace and the protruding hook of his nose can be spotted on every corner, often stacked three high. In a downpour, those hooked noses would have channeled rainwater pouring off the roof, like so many downspouts.

SMALL BALL COURTS

The Great Ball Court with it’s high vertical walls is unlike any other in the Mayan World. A normal court had much lower sloping walls, built at angles that would have made it much easier to knock a ball through the goal ring. There are several smaller ball courts at Chichén Itzá, built in the more traditional style. These may have been practice courts, or perhaps they were used for lesser matches. Either way, they are centuries older than the super-sized court near the entrance to the park.

An older, smaller ball court in old Chichén, missing its goal rings. When in use, the sloping sides were smoothly stuccoed.

MAYAN ARCH

A proper load bearing arch requires a keystone, a block that’s specially carved to fit like a puzzle piece, and bear the weight from two directions at once. The Maya built plenty of arches, but they never quite figured out the keystone business, so Mayan arches are what’s known as corbelled arches, built from two stacks of blocks that lean closer and closer together until they meet at the top. Many of these Mayan arches are so solid, they’ve outlasted the walls or the buildings to which they were once attached.

Corbeled arches at Chichén Itzá

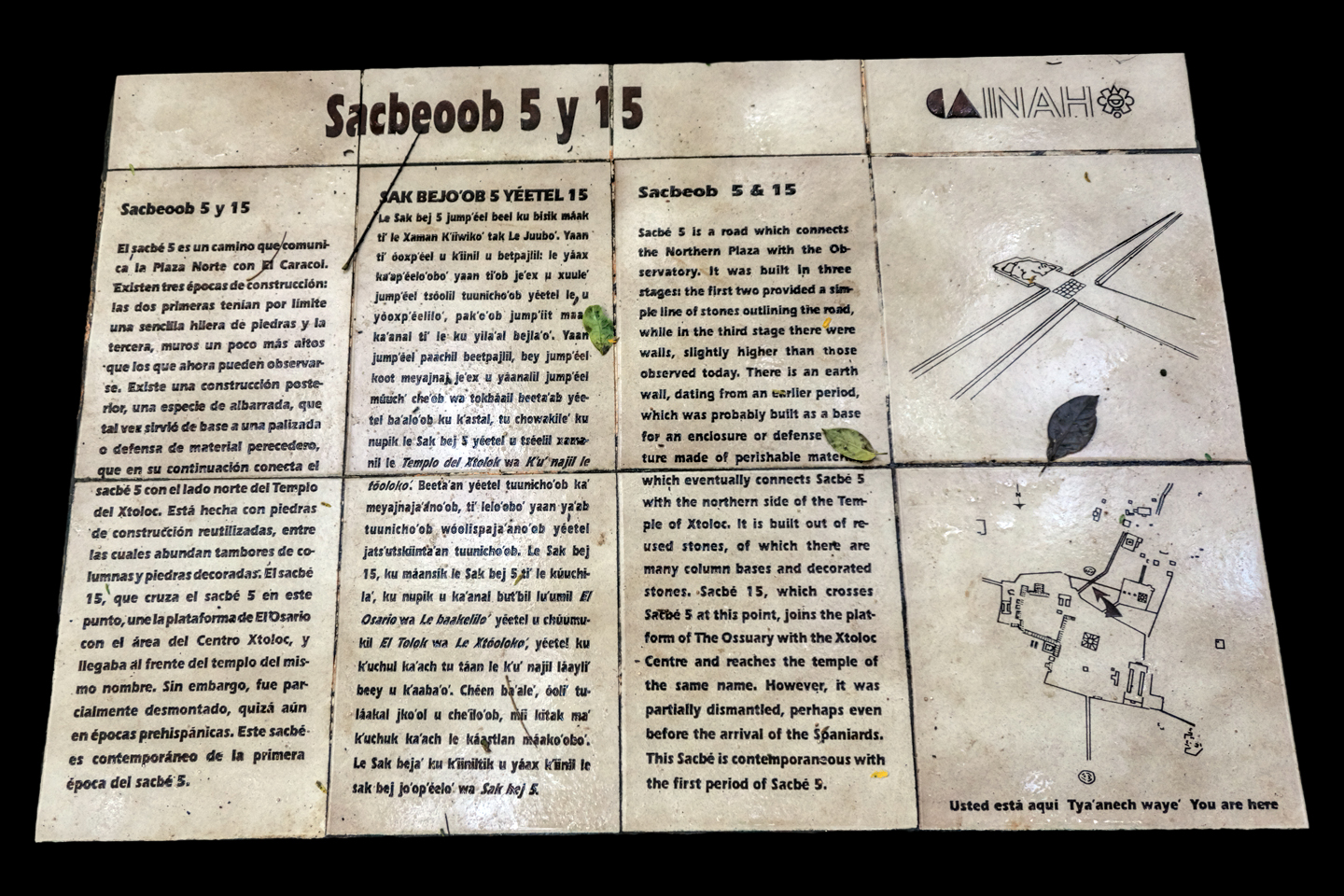

SACBEOB

Different sections of the Mayan cities, indeed, the cities themselves were usually connected by paths known as Sacbés, or collectively as the Sacbeob, the “White Roads.” The Mayans didn’t have draft animals, or the wheel, so goods were transported by human bearers. They used these raised pathways, which were often bordered by low walls, and surfaced with crushed white stone that reflected moonlight, making the paths easier to follow in the cool of the night.

The remains of Sacbés can still be seen at Chichén Itzá, including this one, that leads from the main plaza to the Observatory.

CHACMOOL, AND OTHER CARVINGS

Prominently featured atop the Temple of the Warriors, and at several other locations in Chichén Itzá, there are carved statues known as Chacmools. These are reclining figures, propped up on their elbows holding a bowl in their laps, with their heads swiveled 90 degrees to one side. Some are very realistic, others more primitive; details vary, but the basic configuration is always the same, a reclining figure gazing off to the side. Figures just like this are found all over southern Mexico, including in the Aztec cities in the central highlands.

Among the Aztecs, the bowl held by the Chacmool was a receptacle for the hearts cut from the chests of sacrificial victims. In other locations they held more prosaic offerings, such as tamales, feathers, and incense. The commonality is sacrifice: the carvings were used by the Mayan priests in the performance of sacrificial ceremonies, serving as an altar that helped bridge the gap between the human realm and that of the gods. It’s commonly believed that the Chacmool may have originated at Chichén Itzá, as the examples here are among the oldest ever found.

Carved serpent heads representing Kukulkan are another common element at Chichén Itzá. They are found at the top, or the bottom, and on either side of nearly every staircase, perhaps serving as guardians. The serpent heads appear to have been modular, carved seperately, and then installed, a technique that’s very apparent with this example from the Platform of Venus. This carving also has traces of paint remaining on the surface, blood red on the serpent’s mouth, and greenish blue on the snout.

Soft limestone panels feature elaborate carvings. This one was repaired during the restoration of the ruin, and re-installed

A jaguar throne. A similar carved throne, but painted red, with jade inlays for spots, was found inside the Castillo

CURRENT RESIDENTS

Spiny-tailed Iguánas at Chichén Itzá: fat and sassy!

Every Mayan ruin that we stopped at, from the large, crowded sites like Chichén Itzá to the smaller sites like Edzná, all had one thing in common: they’re crawling with Iguanas! Mexican Spiny Tailed Iguanas, Black Spiny Tailed Iguanas, and Yucatan Spiny Tailed Iguanas, just to name a few. When the Mayans moved out, the Iguanas moved in, and they’ve made themselves very much at home among the ruins.

I’ve never been a bird watcher, but I am a bird lover, and I’ve always enjoyed taking pictures of them, even when I don’t have a clue as to the species. The birds I observed in Chichén Itzá weren’t particularly exotic. No brightly colored parrots with beautiful feathers of the sort prized by the Maya. Mostly just a bunch of bug eaters, similar to the grackles in my yard at home. The biggest difference? These birds live in a Mayan ruin!

The birds of Chichén Itzá: life among the ruins

Chichén Itzá is a fascinating place to visit, despite all the hype, and the reconstructed pyramids, and even despite the crowds. It is the “Quinn-tessential” Mayan ruin (pun intended), so if you’re visiting the Yucatan, even if your only interest is the beaches, you owe it to yourself to climb on a bus, or rent a car, and see the place in person. We can only imagine what it would have been like when it was still in use, with all the sights, sounds, and smells of a living city teeming with people, with the kings and nobles in their palaces, and the priests in their temples. All of that was very real, and not so very long ago. The feathered serpent with the unquenchable thirst for blood may be gone now, or at least fallen out of favor, but as long as the ruins of this ancient city remain standing, he won’t be forgotten.

The photographs in this post were taken during a two day visit to Chichén Itzá in October of 2015. The black and white images attributed to Carl Duisberg were taken in the summer of 1970.

If you’re planning a trip of your own to Chichén Itzá, and you’d like some tips on how to capture the place in photographs, see my previous post: Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

Unless otherwise noted, all of the photographs on this site are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

In conclusion, a little something extra:

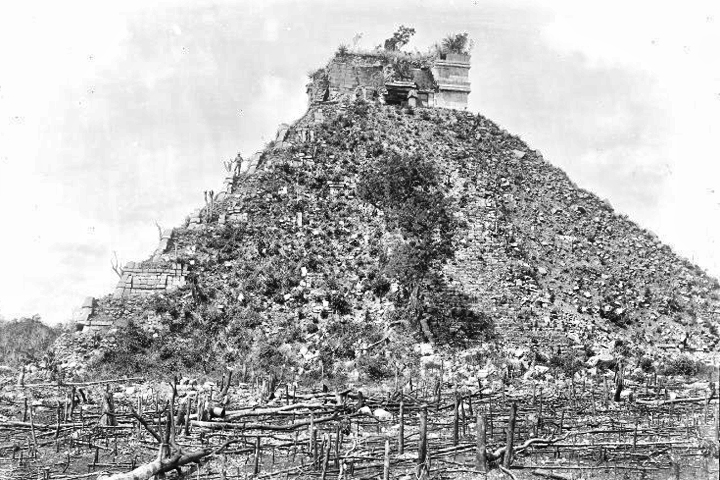

Chichen Itza in 1970:

Original Photographs by Carl Duisberg

My good friend Carl Duisberg has been a world traveler almost as long as I've known him, and I've known him since we were both kids in school.

I recently helped Carl resurrect two dozen rolls of black and white film from some of his early travels, negatives that had been packed away for half a century and essentially forgotten. No prints were made when the film was processed, all those years ago, so when I scanned and edited the images, I brought wonderful photos to life that had never been seen before.

One of those rolls of film was shot in the ruins of Chichén Itzá, more than fifty years ago, and Carl has graciously agreed to share them here. Viewing these old photos, it's apparent how much work has been done cleaning up the ruin. In 1970, many of the structures you see today were still half buried, and the walkways for visitors were unpaved dirt paths. At that time, visitors were still allowed to climb the pyramids, and several of Carl's photos show views that could not be captured today. The lack of crowds is certainly worthy of note: Cancun was still being built at that time, and was not yet open for business. These pictures were taken several years before the hordes of tourists arrived in the Yucatan.

(If you'd like to see more of Carl's work, check out the Historic Photos section of this website.)

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

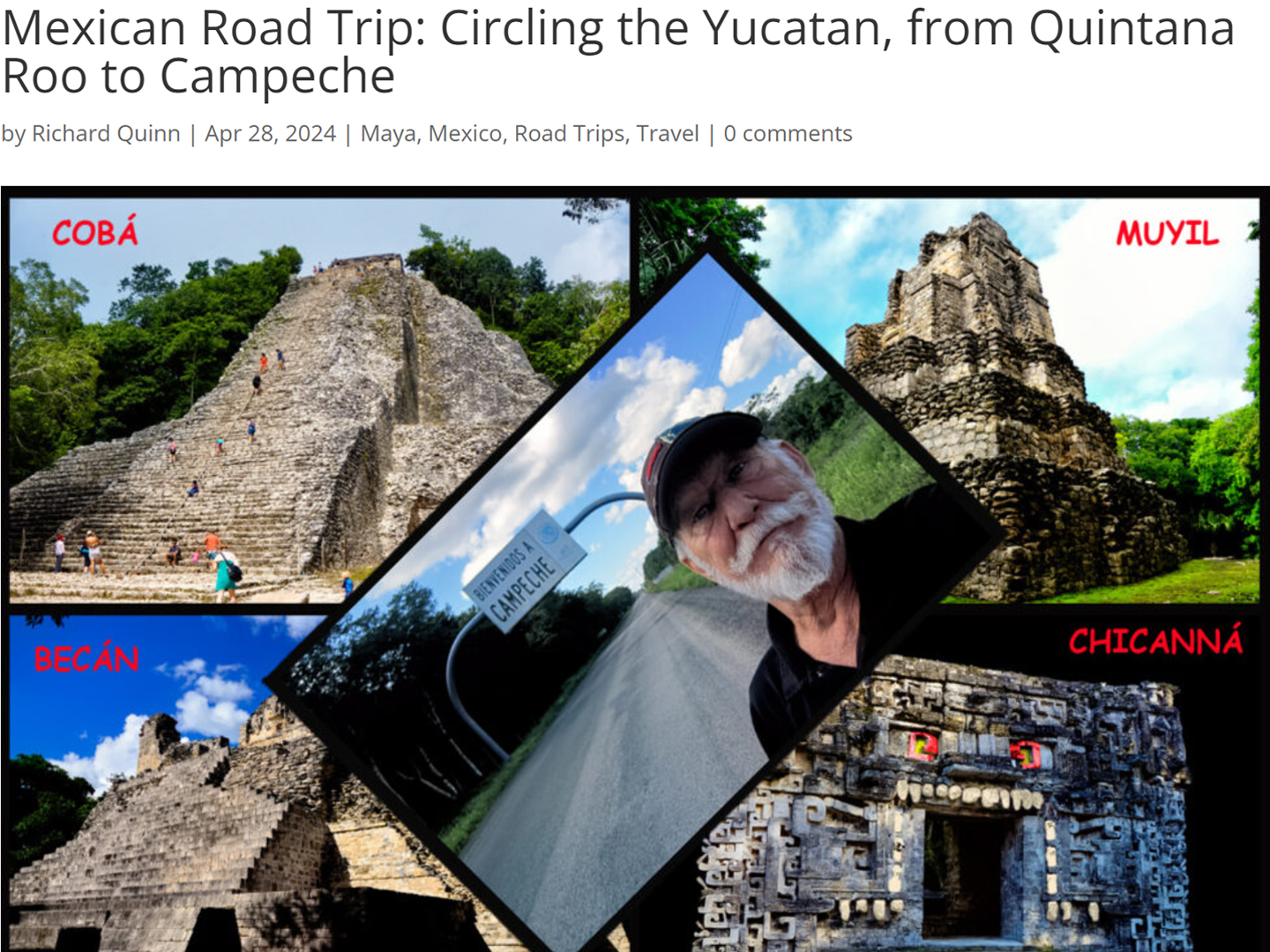

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn’t huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

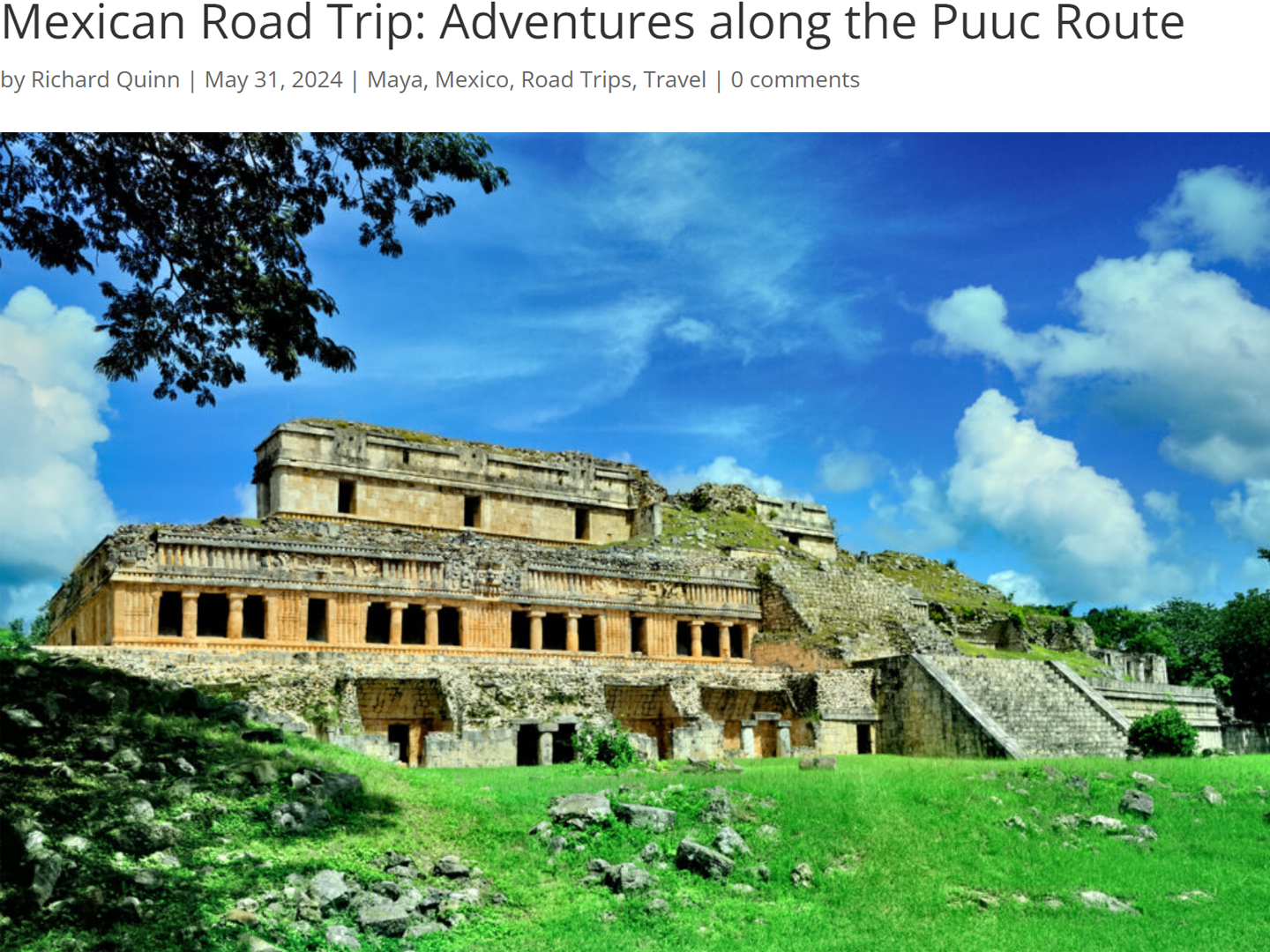

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

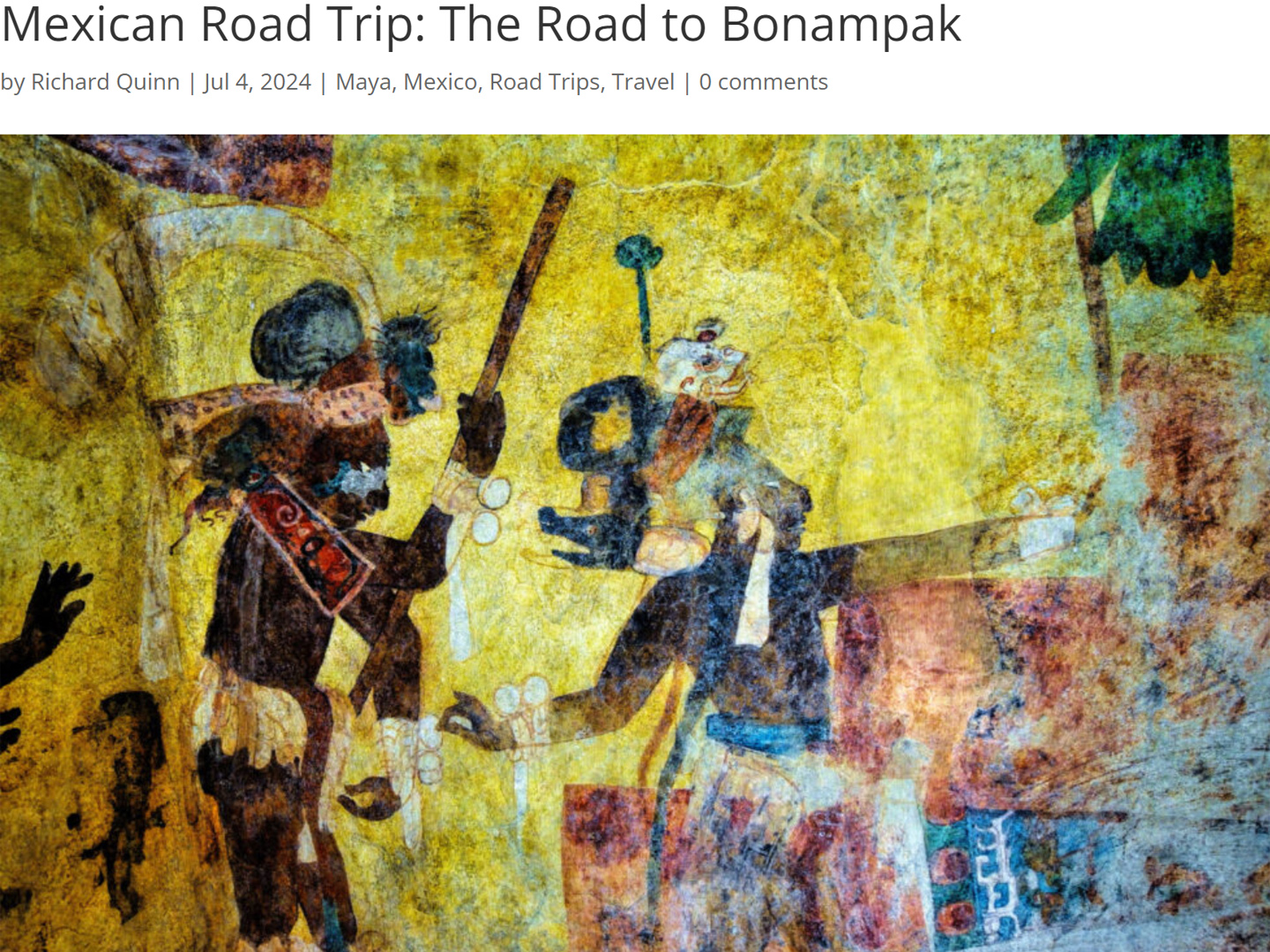

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we’re left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it’s 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in March, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico’s Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they’ve adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It’s a wonderful, colorful parade that’s all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. “Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins” was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after “Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali.” We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments