This is the second page of a longer article about Canyon del Muerto. If you’d like to begin at the beginning, click the button to return to Page 1:

We drove another mile or so, traveling slowly. The canyon would widen for a bit, and then it would narrow again between the sandstone cliffs. Nearly all of the wide spots were under cultivation, odd-shaped plots of plowed ground, lying fallow in mid-October.

Forty different Navajo families own land inside the canyon, and all of them lived there all year around at one time or another, growing crops and raising livestock, braving the dangers of seasonal floods and bitterly cold winters. Modern conveniences have drawn most of the current generation to a more comfortable life in town, but many of them maintain an important connection to the canyon, operating the tour companies, and working as guides. Sylvia had been doing that herself for almost 30 years, and it was obvious that she still enjoyed it.

CEREMONIAL CAVE

“Pull over here,” she said, directing me to stop by a stock gate. “This one is Ceremonial cave.” Sylvia pointed to a dark hollow in the face of a cliff, adjacent to an alcove filled with crumbling ruins.

I trained my zoom lens on the scene, and got some decent photos from where we stood. Many of the archaeological sites in the canyon, including some of the major ruins, are located on private Navajo land. You can only get just so close, because there are fences, and, even more important, there are property rights to consider. If your guide has the specific permission of the landowner, you get to pass through unlocked gates to get closer. Otherwise? You stay on the outside of the fenced area, and use binoculars and a telephoto lens!

“There are three kivas, and two storage bins,” Sylvia explained. “That’s a very old ruin, from 300 BC. You can’t get into that one, the footholds and all of that have been destroyed. This one is made different than all the others; the doorway is skinny, so you have to walk in sideways instead of crawling into their homes, like in most of the ruins. And over here is the pit house, where they had their ceremonies. The Ceremonial Cave.”

We bumped along the sandy track for a few minutes, sticking close to the left-hand side of the canyon, where sandstone cliffs, resembling monumental pastries, rose in layers that were stacked at least eighty feet overhead. The cottonwoods were just beginning to turn, but here and there were a few individual trees well ahead of the rest, already engulfed in the flaming golden yellow of autumn. I was watching my odometer, so I knew that we’d travelled just under three miles from the Junction when Sylvia asked me to stop again. Just up ahead, there was a natural alcove filled with ruins, at least twenty feet above the canyon floor.

LEDGE RUIN

“That’s Ledge Ruin, where I used to play around,” Sylvia informed us. “We were always told not to be afraid of the ruins. because the spirits of the people that lived here in the canyon, their spirits were still here, but we didn’t have to be afraid of them.”

It’s a remarkable thing to imagine, but Canyon del Muerto was Sylvia’s playground when she was a toddler. Along with her siblings, she had the run of the place, and that included all the ruins. Of course, they were under strict orders not to damage anything, and if they came across pottery or other artifacts, they were told to leave such things where they found them. From a very young age, Navajo children are taught to respect the art and artifacts left behind by the Anasazi; they realize that such things are more than curiosities for the tourists; they are also aware of the historical, cultural, and spiritual importance of these relics of the ancient past.

Ledge Ruin was one of several major sites in the canyon excavated by archaeologist Earl Morris, who worked there over several seasons in the 1920’s.

According to the National Park Service:

“Ledge Ruin sits on a ledge in Canyon del Muerto where the canyon walls bend, creating a natural amphitheater. When standing beneath the ledge, a whispering voice can be amplified, while voices, music, and other sounds echo off the canyon walls.”

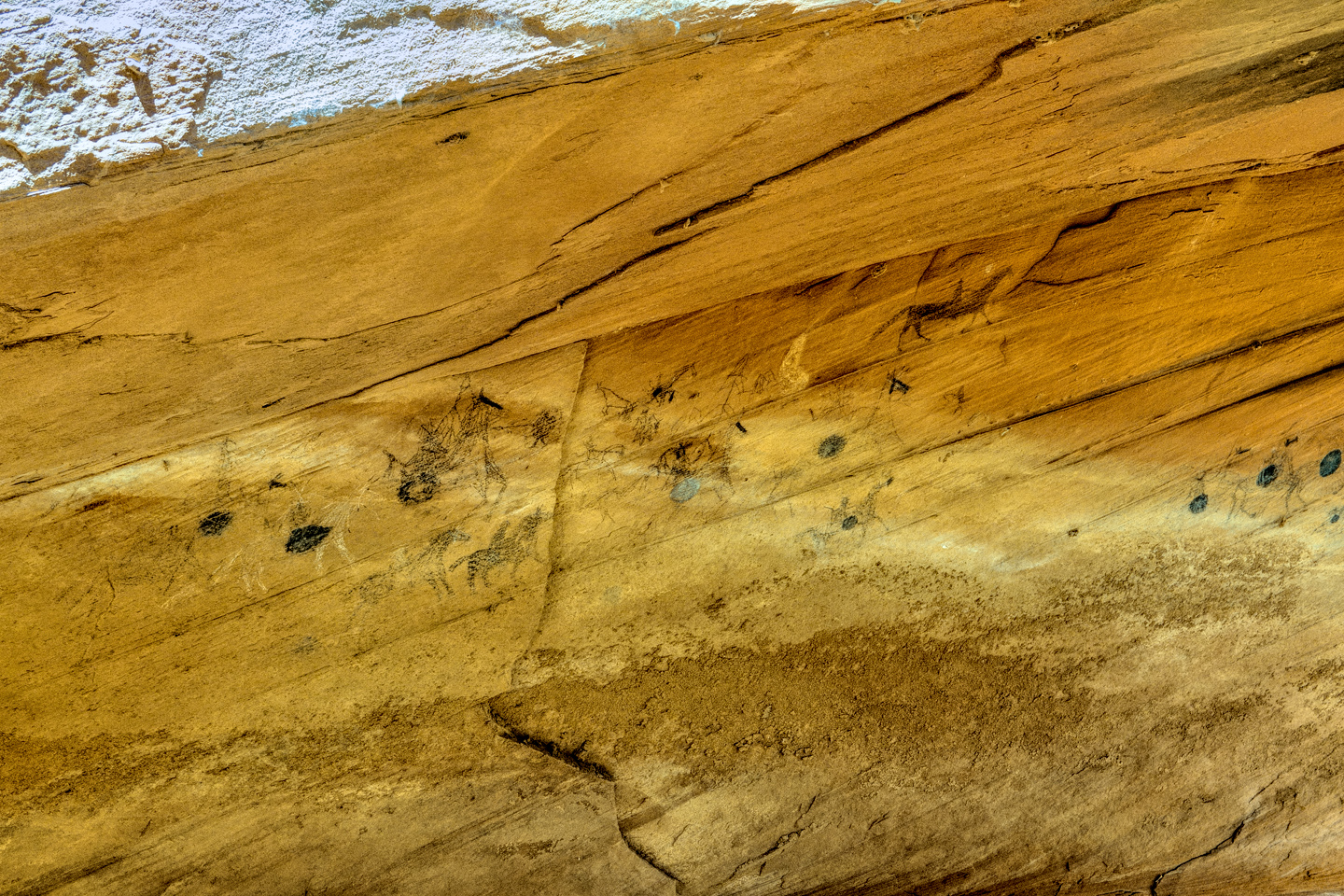

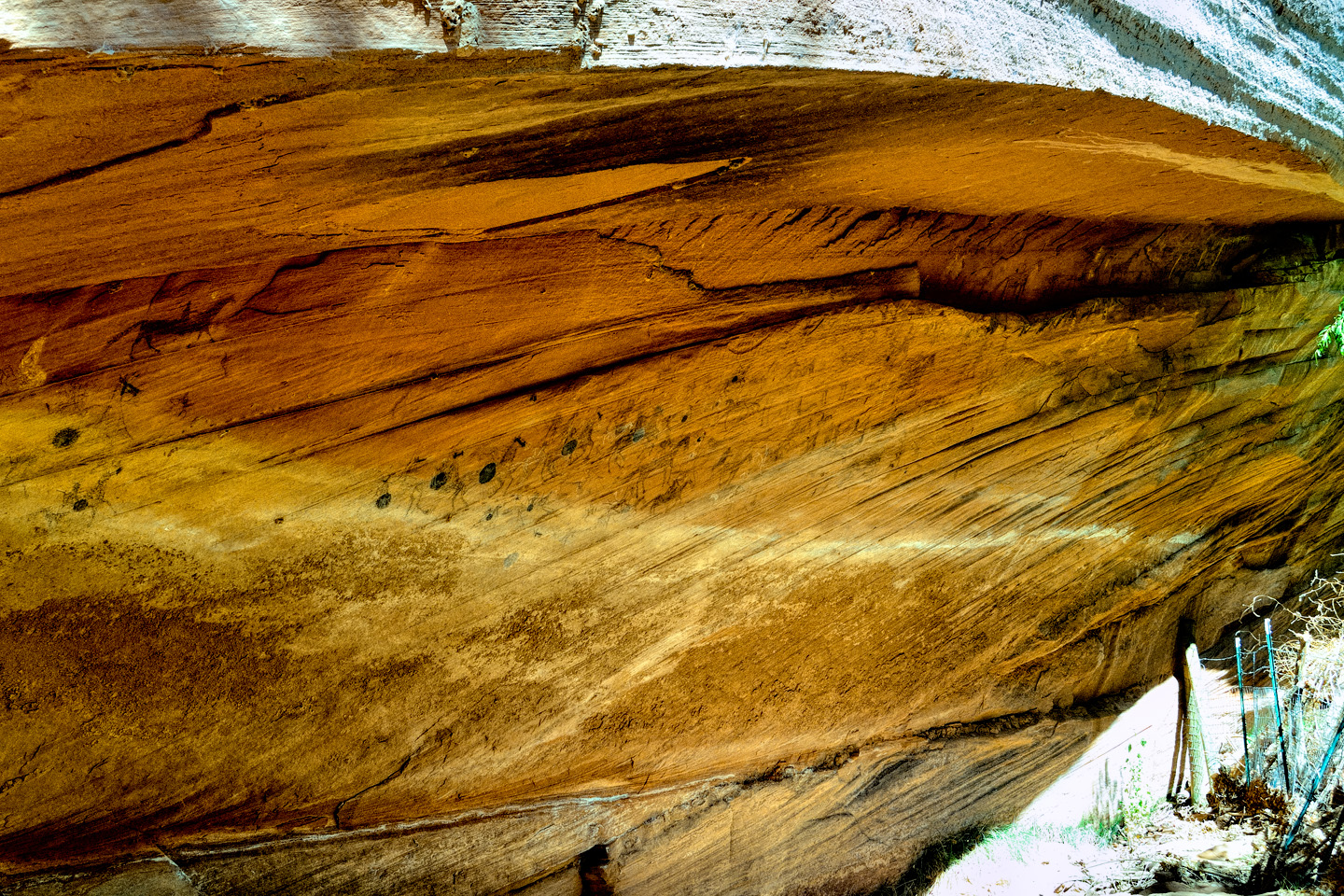

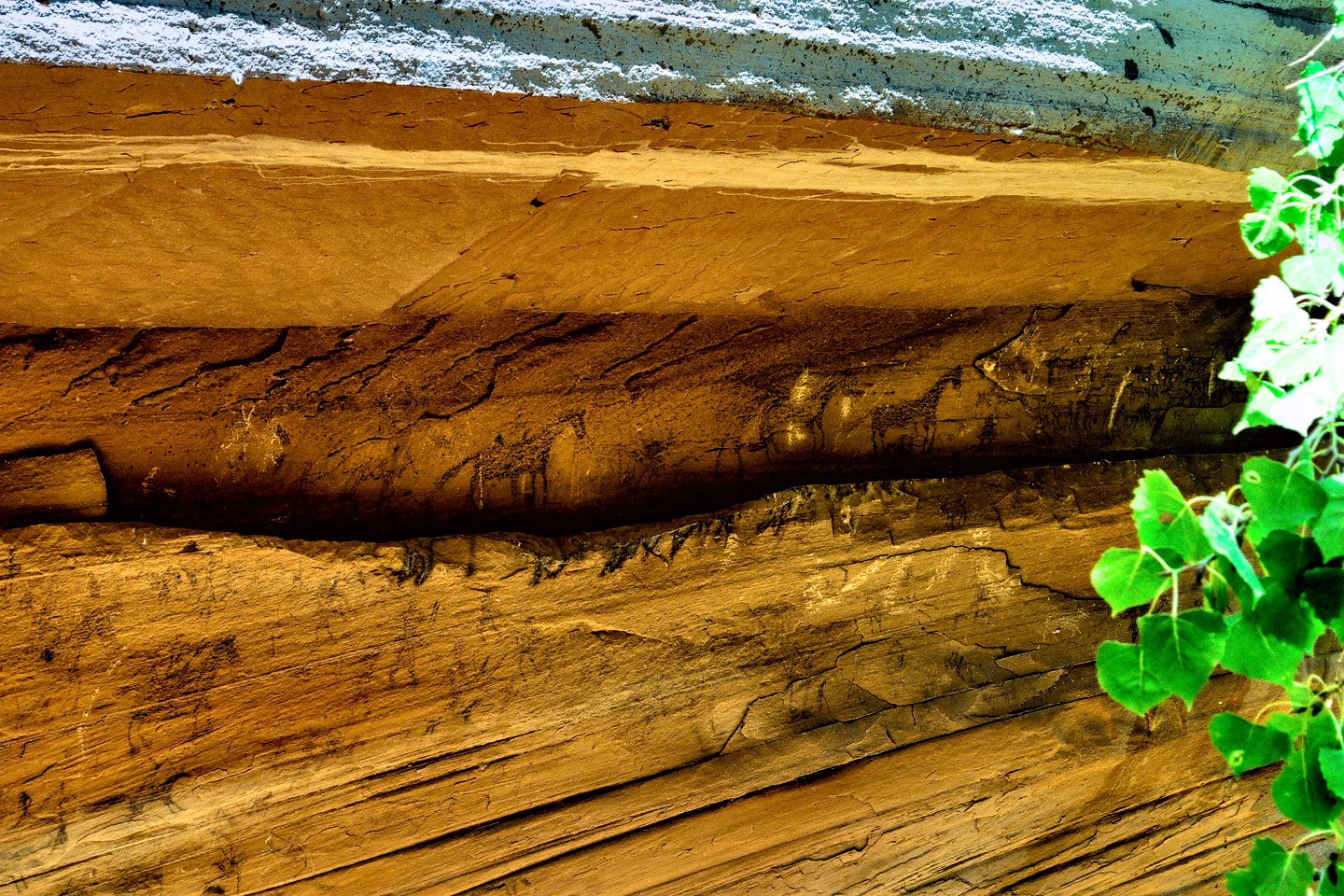

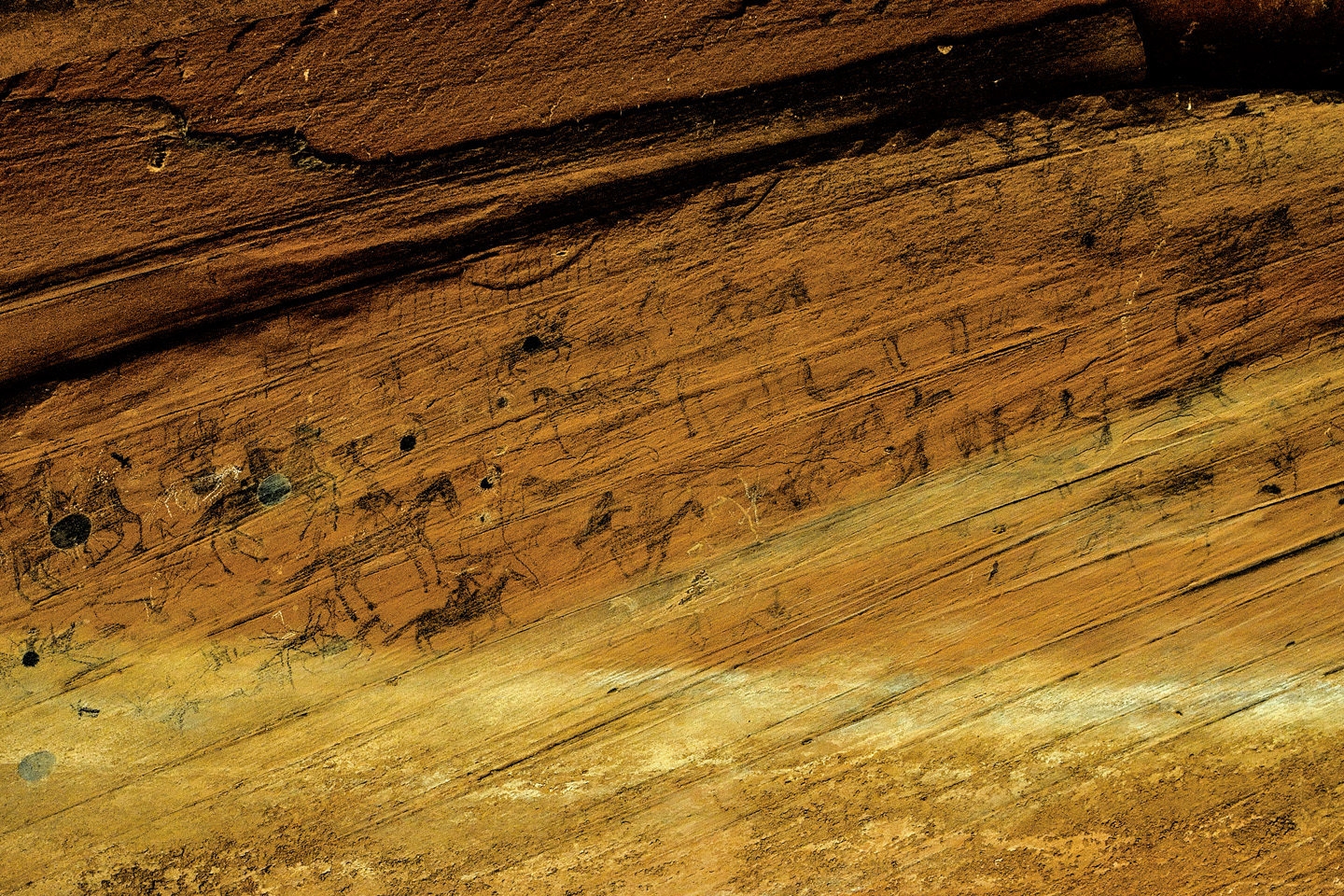

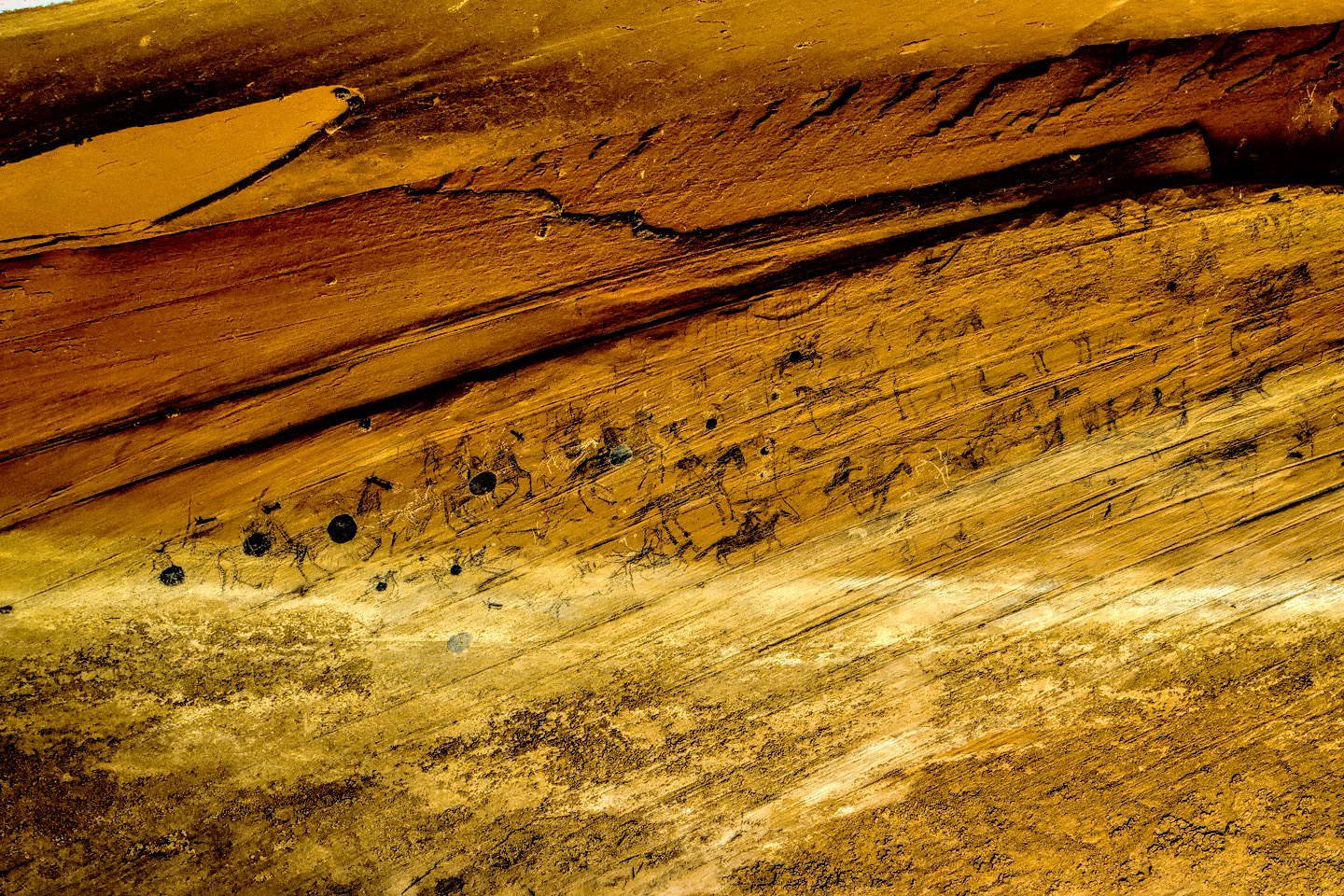

Another mile further along, Sylvia asked me to pull over to the side again. We got out, and walked through the trees to a place where a thirty-foot long segment of the sandstone cliff had crumbled away near the base, leaving a section of wall that was set back a couple of feet, protected by an overhang. We could see black pictographs of horses and riders filling that rough stone canvas from left to right.

UTE RAID PANEL

“That one is the Ute-Raid panel,” said Sylvia. “The Utes used to come on horseback to attack the Navajo people. Their shields and their bridles were very very unique, because they raided the Spaniards, and took silver that they used to make their halters and everything. Their horses were really decked out, you could say, and they used them in wars like that. They were our number one enemies, and they would come here like that and fight.”

So these are the Utes,” she said, pointing to the horses with the round black shields. “You can see the soldiers, and the Spaniards back up here. The Utes used to raid anybody; they didn’t care who it was, they just raided everybody. This one right here, these are Navajo, and right up here, these are Yei bi Cheis. These are winter dancers. The only time the Navajos have their dances is in the winter, from October to January. They have these dances for four months; a very sacred ceremony that they do; and so during that time is when the soldiers were rounding up the Navajo people, and during that time is when the Utes were attacking the Navajo. You can see the soldiers standing here holding their guns. This is the time when the long walk was taking place, when soldiers were rounding up the people.”

Several stories are told about this panel, which was drawn by an unknown Navajo artist in the mid to late 1800’s. It’s a well established fact that there was ongoing conflict between the Navajos and the Utes. In this pictographic sequence, the Utes are on the left, mounted on horseback, with shields and lances, while the Navajos are on the right, on foot, and clearly outnumbered.

In one version of the story, just as in Sylvia’s account, the attack took place during a Night Way healing ceremony, in the winter, catching the Navajo by surprise, and at a deadly disadvantage.

The drawings are charcoal, except for the shields, which were painted with pigment made from the bee weed plant. The sandstone overhang provides some protection, but after 150 years or more, the panel is weathering, starting to fade and flake away. Many of the rock art panels in these canyons are in danger of irreversible deterioration from exposure to the elements. Pictographs such as these, done with charcoal and other natural pigments, are particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time.

To continue reading this post, click the button below:

Disclaimer: the narrative in this post includes dialogue attributed to my Navajo friend Sylvia Watchman, who was our guide on a two-day tour of Canyon de Chelly in October of 2013. The dialogue in the post is based on the transcript of an audio recording made two years later, when I visited Sylvia in Chinle, and we reviewed my photos from the trip. There was minor editing for grammar and continuity. I take full responsibility for any errors or omissions.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs on this site are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any photo to expand the images to full-screen, with captions:

MORE ABOUT CANYON DE CHELLY:

The Most Beautiful Place on Earth:

A Guide to Canyon de Chelly National Monument

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

Canyon de Chelly: Part 1: The Rim Drives

Most of Canyon de Chelly can only be seen by visitors who are accompanied by an authorized guide, but the Rim Drives are free of charge, no reservation required. Two roads, Indian Route 7, and Indian Route 64 diverge at the entrance to Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Route 7 follows the South Rim of the multi-pronged formation, providing access to seven overlooks, all with killer views into Canyon de Chelly. Route 64 follows the North Rim, and provides access to three more overlooks, with excellent views into the branch known as Canyon del Muerto.

The South Rim drive is a 36 mile round trip, from the Welcome Center to the Spider Rock Overlook and back again, making multiple stops in between. You’ll need a couple of hours to do it justice, depending on how much time you spend at each of the different overlooks. The North Rim drive is shorter, just over 26 miles round trip to the Mummy Cave Overlook. That drive requires another hour and a half, bare minimum, so if you’re going to do both, you should play it safe, and set aside half a day. I can guarantee you’ll consider it time well spent! <<CLICK to Read More!>>

The South Rim Drive

Indian Route 7 begins at the turnoff from US 190, and serves as the main road in the Navajo town of Chinle. If you follow it headed east, it will take you directly to the Visitor Center for the Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Stop there to pick up a map of the park, and to get current information about guided tours and other activities, as well as road conditions, and any closures that might affect your visit.

From the Visitors Center, bear right at the fork to stay on Indian Route 7, the South Rim Drive, and follow the signs to the overlooks.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

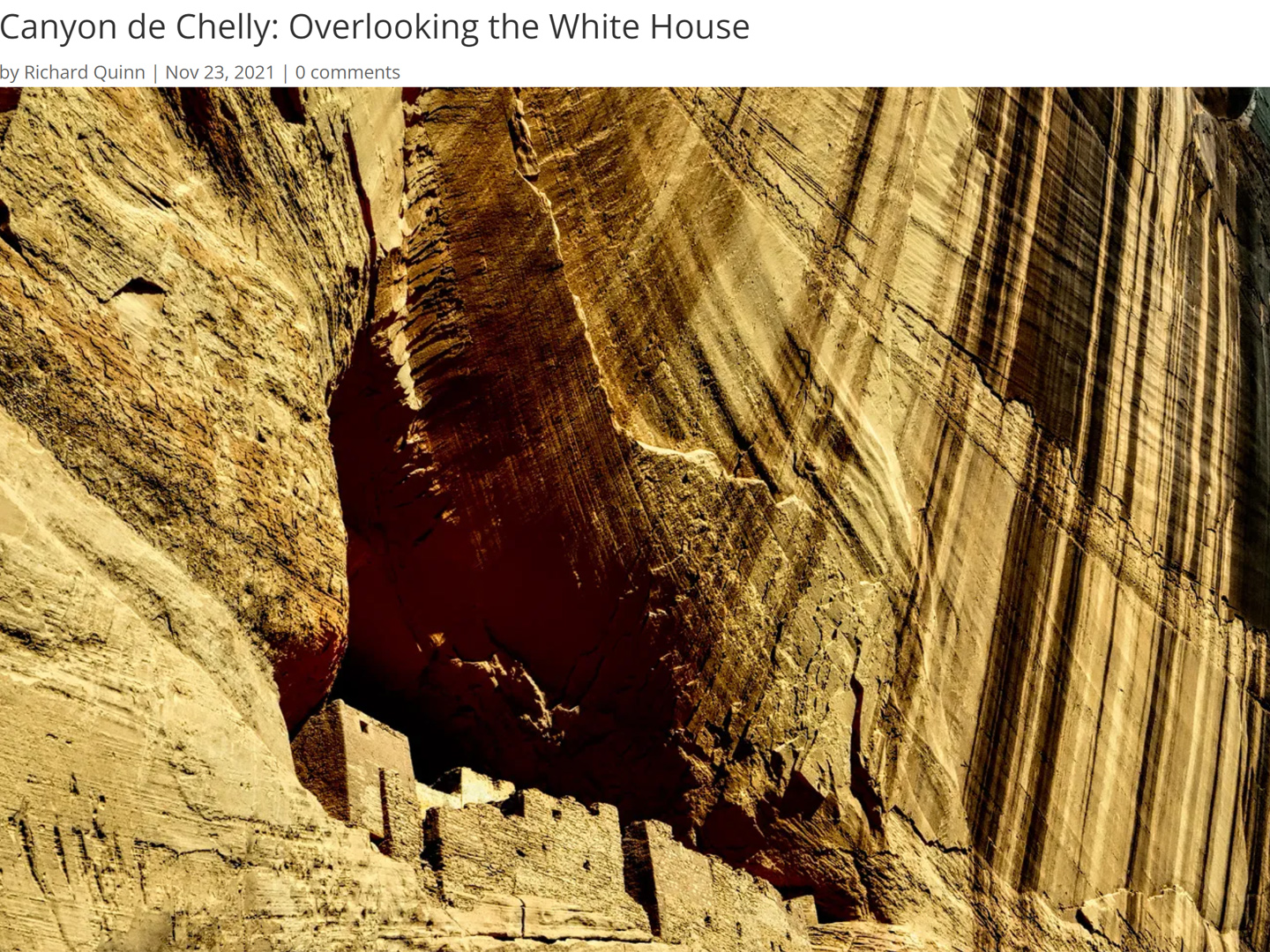

Overlooking the White House

A mile and a half beyond the Junction Overlook you’ll reach the turnoff for the White House Overlook, which is at the end of a half-mile long access road. (Note: the access road, the overlook, and the trail to the White House ruin are currently closed to visitors.) The White House Overlook has always been one of the most popular. The vantage point offers a fabulous panorama of the Canyon, along with an unobstructed view of the White House, one of the best preserved ruins in the National Monument.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The North Rim Drive

Most visitors to Canyon de Chelly National Monument focus the bulk of their attention on the South Rim Drive, but in my view, your trip simply won’t be complete if you don’t take in the North Rim Drive as well.

Seven miles from the Welcome Center is the turnoff to the Antelope House Overlook, which is two miles further along a paved access road. The payoff is a fabulous bird’s-eye view of a quite wonderful Anasazi ruin known as the Antelope House. You can still see the crumbling foundations of dozens of rooms, a tower, and at least four circular kivas...

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

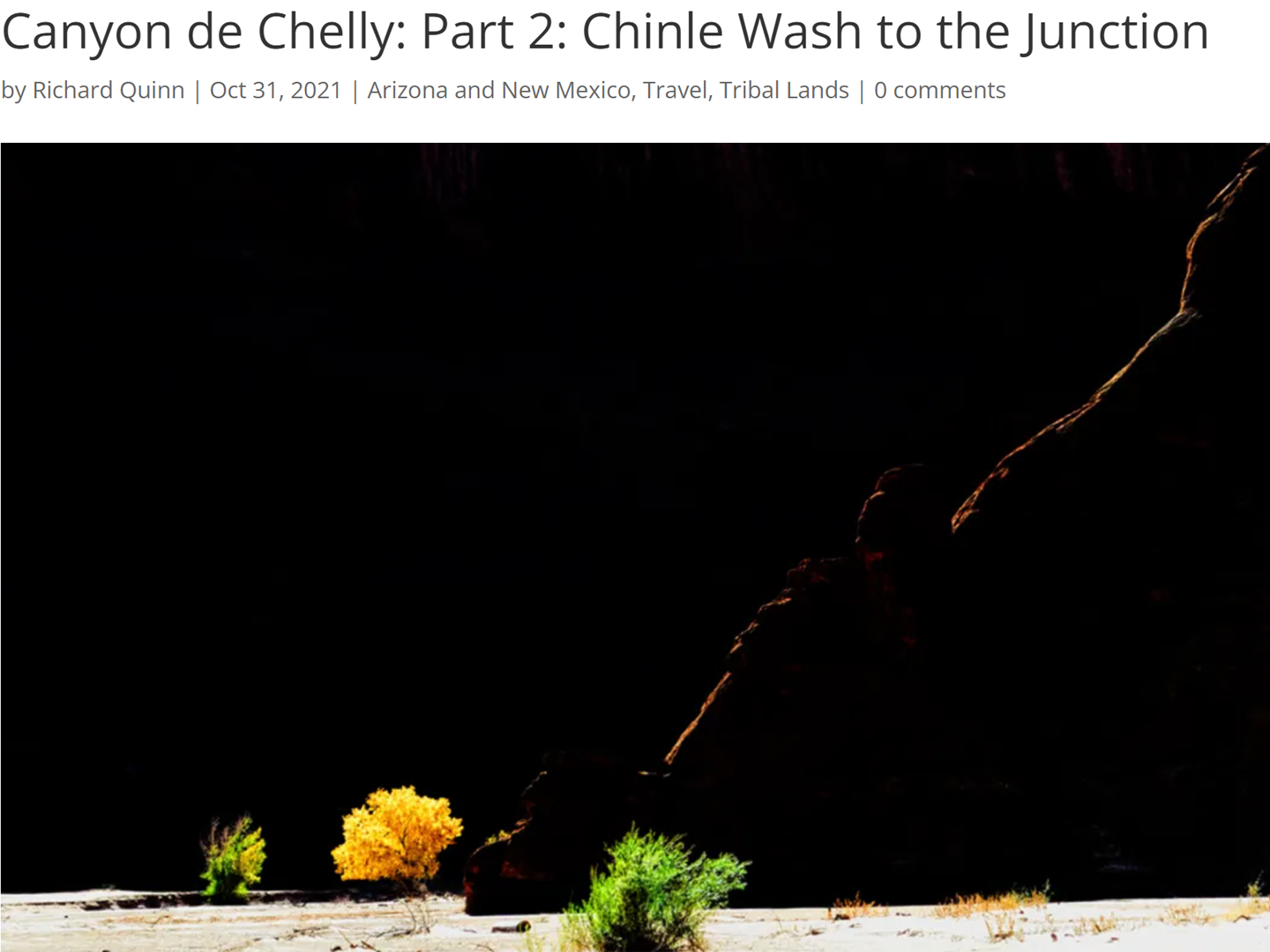

Canyon de Chelly: Part 2: Chinle Wash

Canyon de Chelly National Monument is a place for the whole world to enjoy and admire, just like all of our national parks and monuments, but at Canyon de Chelly there is an essential difference: the rim drives and most of the overlooks offering views into the beautiful canyon are open to the public all year around. The canyon itself, including all hiking trails and Jeep tracks, all the ruins and the rock art, in essence, anything below the canyon rim, all of that is private property, off limits to everyone save the handful of Navajo families who own the land on the canyon floor.

The rest of us can go in, but only to certain areas, and only if we’re accompanied by an authorized guide. A Navajo guide can take you into the canyon in their SUV, or, if you prefer, you can join a guided hike, or a trail ride on horseback. The standard Jeep tours, which are the most popular, range from three to six hours in length. The longer tours cover the highlights of both of the primary gorges, Canyon De Chelly, and Canyon del Muerto.

The series that follows is a detailed account of my own experience in this remarkable place. <<CLICK to Read More!>>

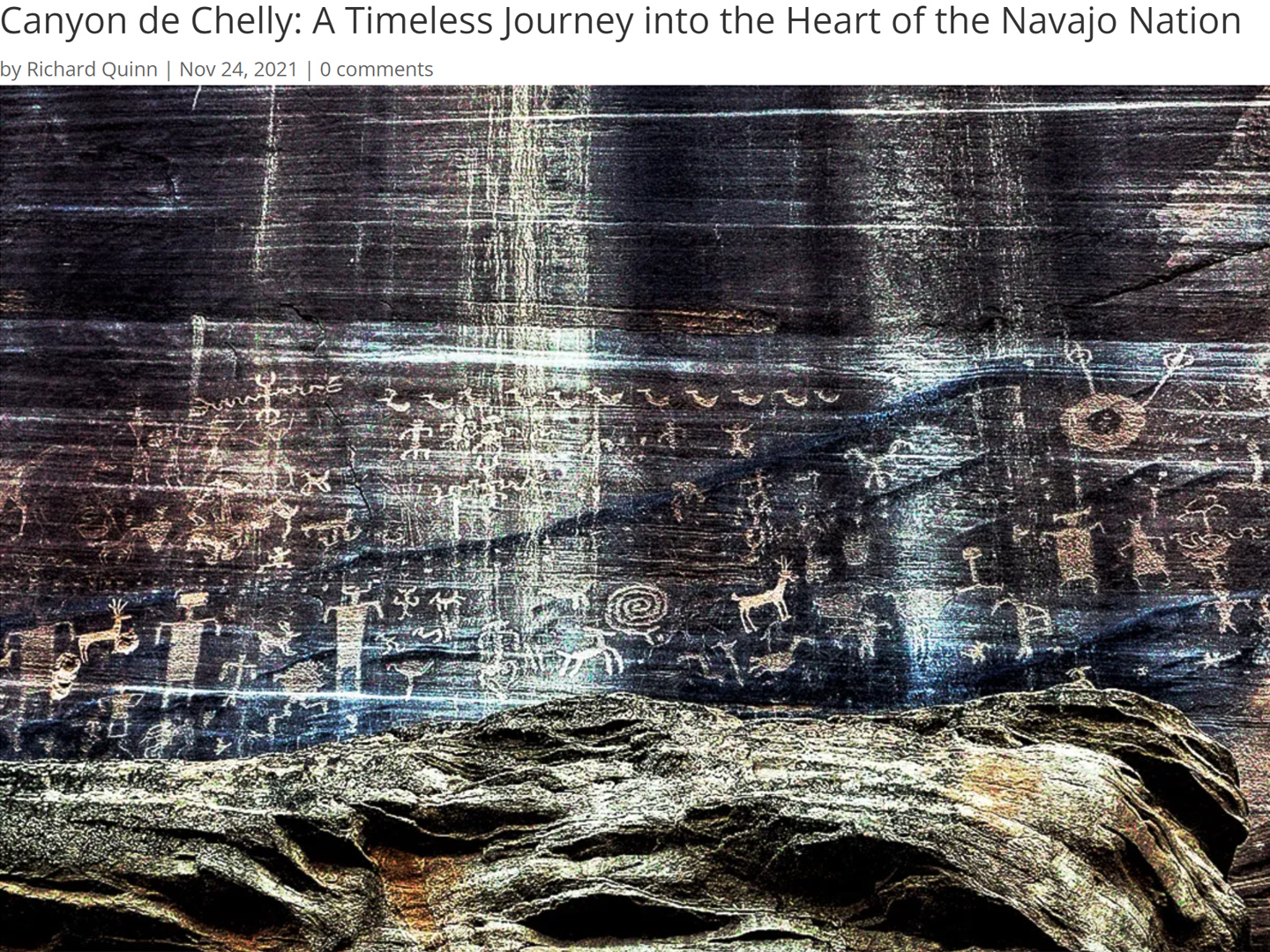

A Timeless Journey into the Heart of the Navajo Nation

At the beginning of our trip, we asked Sylvia to show us her favorite petroglyphs, along with the usual ruins and rock formations, and she did not disappoint. Our first stop, very near the mouth of the canyon was a prehistoric bulletin board she called Newspaper Rock. A smooth segment of cliff face coated with dark desert varnish, featuring an area at least forty feet wide filled hundreds of petroglyphs. The symbols weren’t carved into the rock, and they are not painted. These artists pecked away the dark varnish, creating their pictures by exposing the lighter colored rock underneath: antelope, birds, hunters, and a multitude of intriguing symbols.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

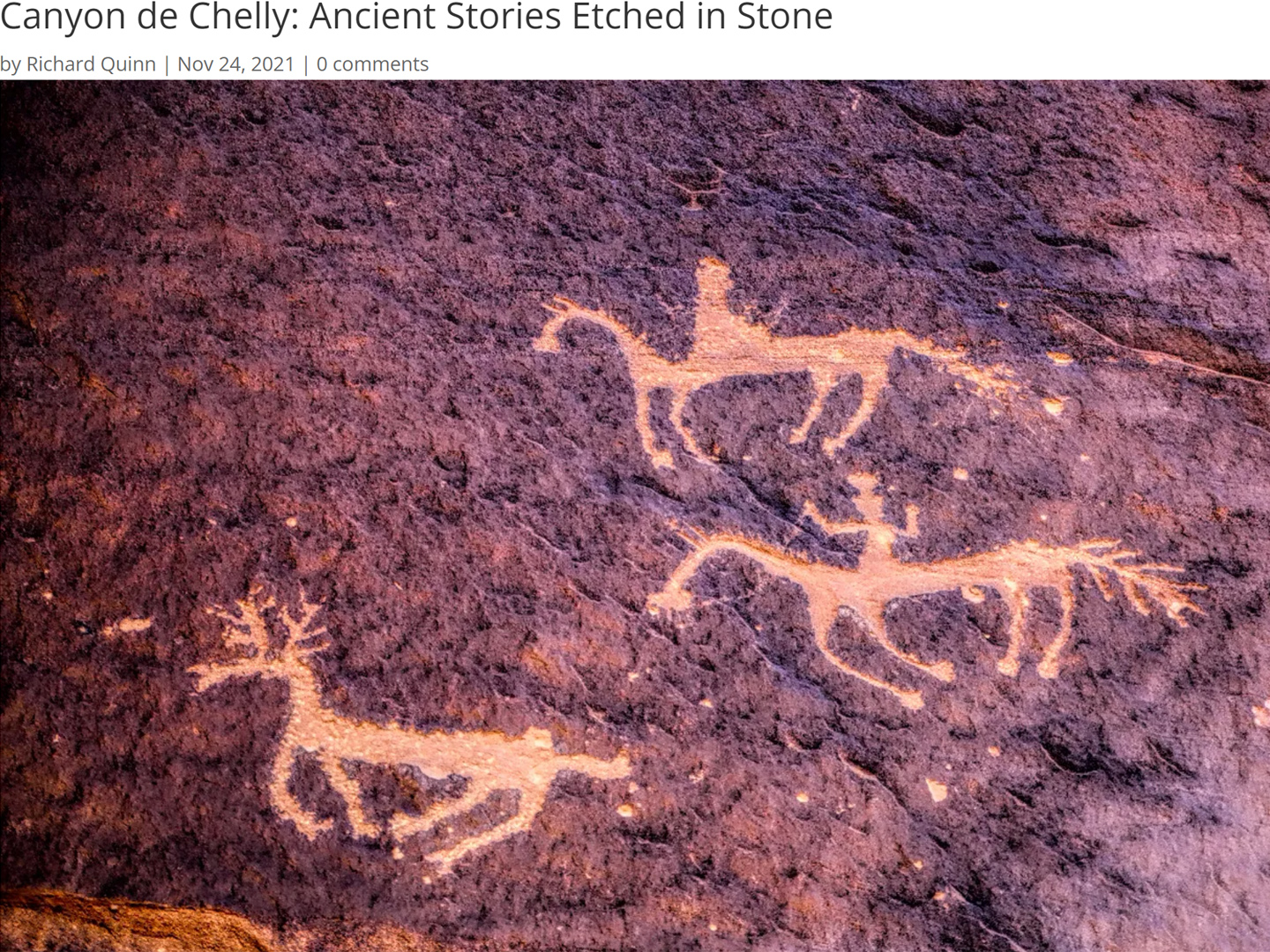

Ancient Stories Etched in Stone

A short distance from Newspaper Rock, just a few steps away along the base of the cliff, we came to another set of petroglyphs featuring riders on horseback. These were most certainly Navajo, and likely date back to the 1800’s. They shared this shady space with other images that were obviously much older. There were hunters, deer, birds, handprints, and more. We crowded in close for a better look.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

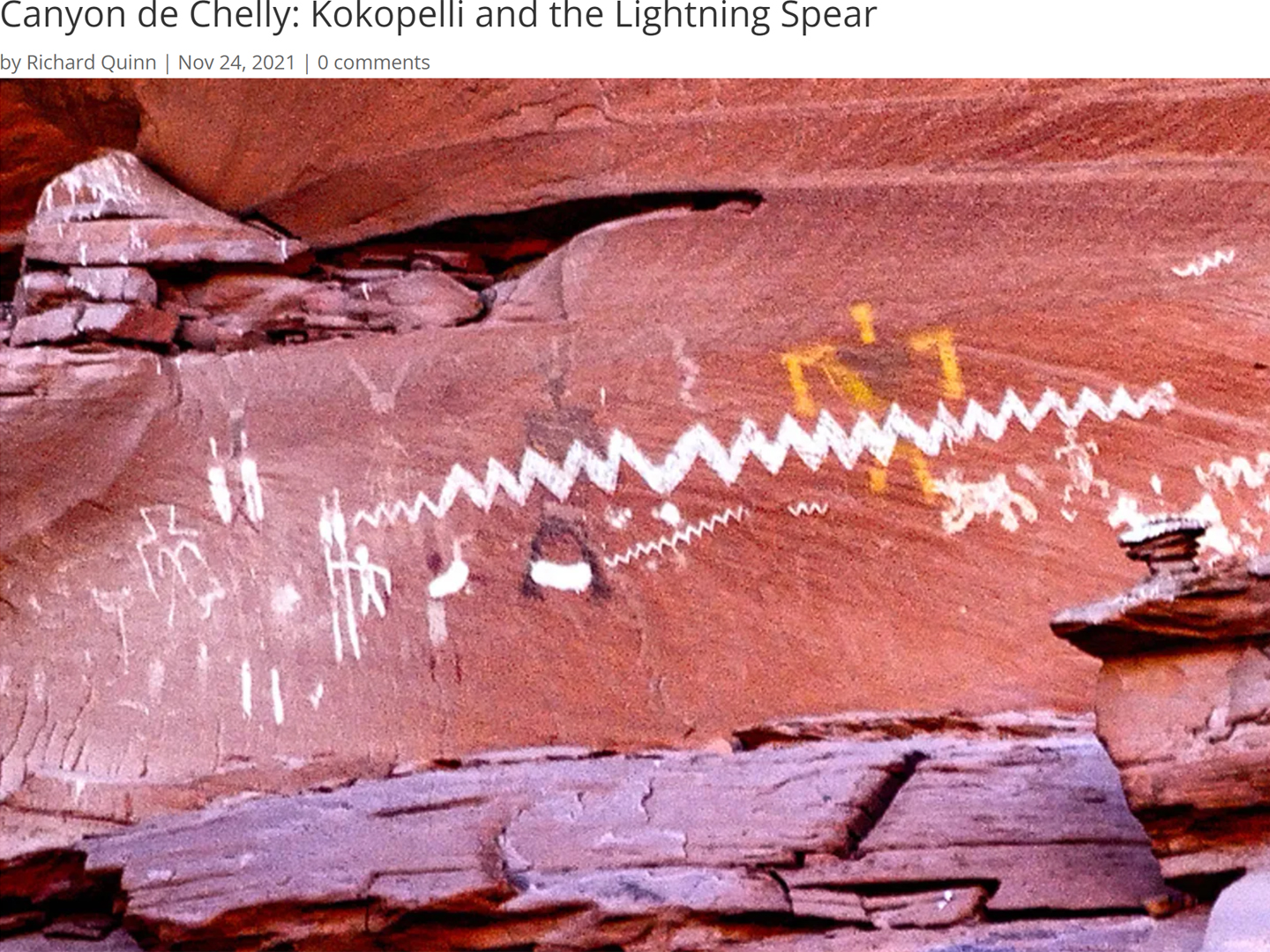

Kokopelli and the Lightning Spear

“When you look at this, there’s a man holding a staff; out of the staff there’s this energy that’s coming out. The figure in black is the patient. The one in yellow is the shaman. The important men of the village are up on the side here, so this was a very sacred ceremony that they were doing. And there are some other drawings on the side; this one here is like a figure of the holy people, because it’s way up there, and it only has the head, and not the arms or the legs. You see a lot of people drawn, and there’s a bird there. And these are drawings of, like, clan systems. The bear, the turtle, and the antelope down here.”

I was probably getting a bit starry-eyed at that point. Barely three miles into the canyon, we’d traveled a thousand years in just under a hundred minutes, and we were barely even underway!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

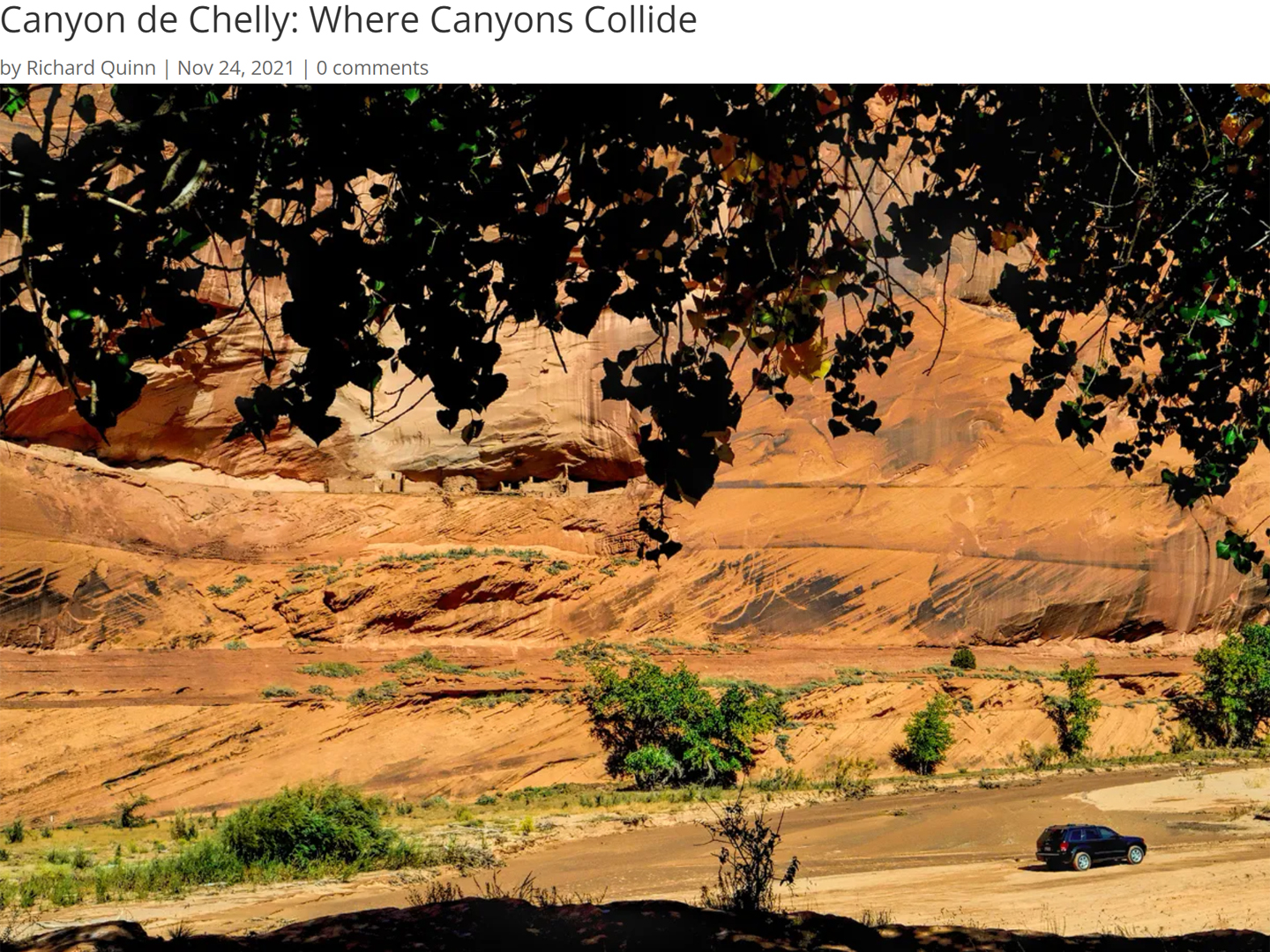

Where Canyons Collide

Just around the bend the canyon opened up into an area wider than any other we’d seen, and right in the middle was a monolithic block of sandstone known as Dog Rock. To the left was the north fork of the canyon, Canyon del Muerto, and to the right, the south fork, Canyon de Chelly itself. The cliffs soared at least 200 feet above our heads, and halfway up the sheer face opposite was another alcove filled with crumbling adobe, a site called Junction Ruin. A bit smaller than First Ruin, and a bit less well preserved, this is an Anasazi structure dating to the same approximate era. The ruin is clearly visible from above at the Junction Overlook on the South Rim Drive; it looks a bit different when viewed from below...

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Canyon de Chelly: Part 3: Canyon del Muerto

The left hand fork is the spectacular work of nature known as Canyon del Muerto. The star attraction of this route is the Mummy Cave Ruin, the largest in the area, built on a ledge between a pair of deep caves, high on the face of a cliff in an extraordinary natural amphitheater. It’s a 24 mile round-trip from the Junction, twelve miles of rough road in each direction, with enough twists and turns to qualify as a carnival ride–along with plenty of mud! Along the way you pass the Ledge Ruin, Antelope House Ruin, Navajo Fortress, and Standing Cow Ruin, along with some extraordinary rock art.

The most popular tours last between 3 and 4 hours. Most of them travel into both canyons, but don’t go all the way to the end of either road. Only the longer tours include Spider Rock or Mummy Cave, and only the all day tours include both. Private tours offer the most flexibility, and in most cases, a more comfortable ride.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

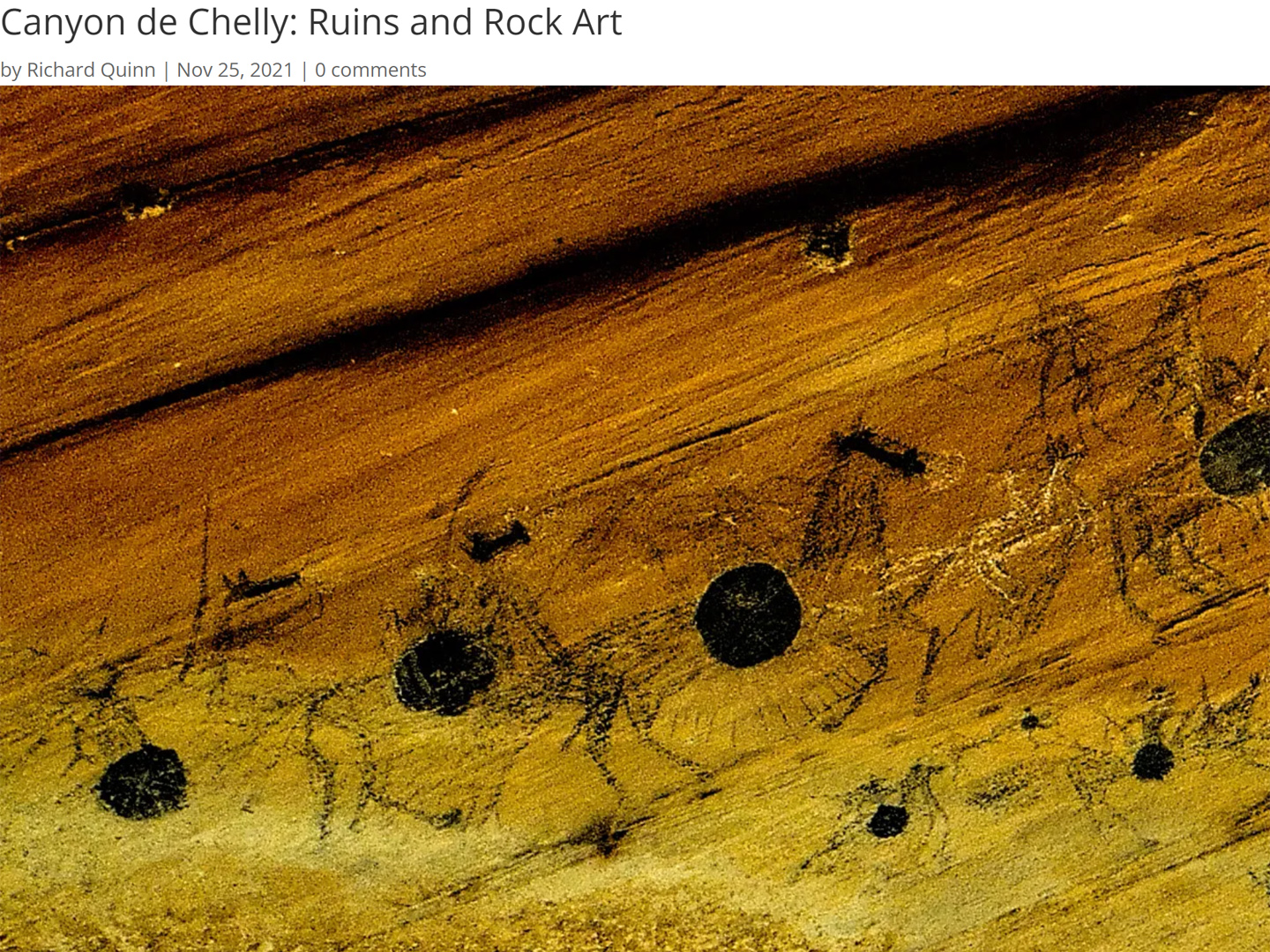

Ruins and Rock Art

In this pictographic sequence, the Utes are on the left, mounted on horseback, with shields and lances, while the Navajos are on the right, on foot, and clearly outnumbered. In one version of the story, just as in Sylvia’s account, the attack took place during a Night Way healing ceremony, in the winter, catching the Navajo by surprise, and at a deadly disadvantage.

The drawings are charcoal, except for the shields, which were painted with pigment made from the bee weed plant. The sandstone overhang provides some protection, but after 150 years or more, the panel is weathering, starting to fade and flake away. Many of the rock art panels in these canyons are in danger of irreversible deterioration from exposure to the elements. Pictographs such as these, done with charcoal and other natural pigments, are particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

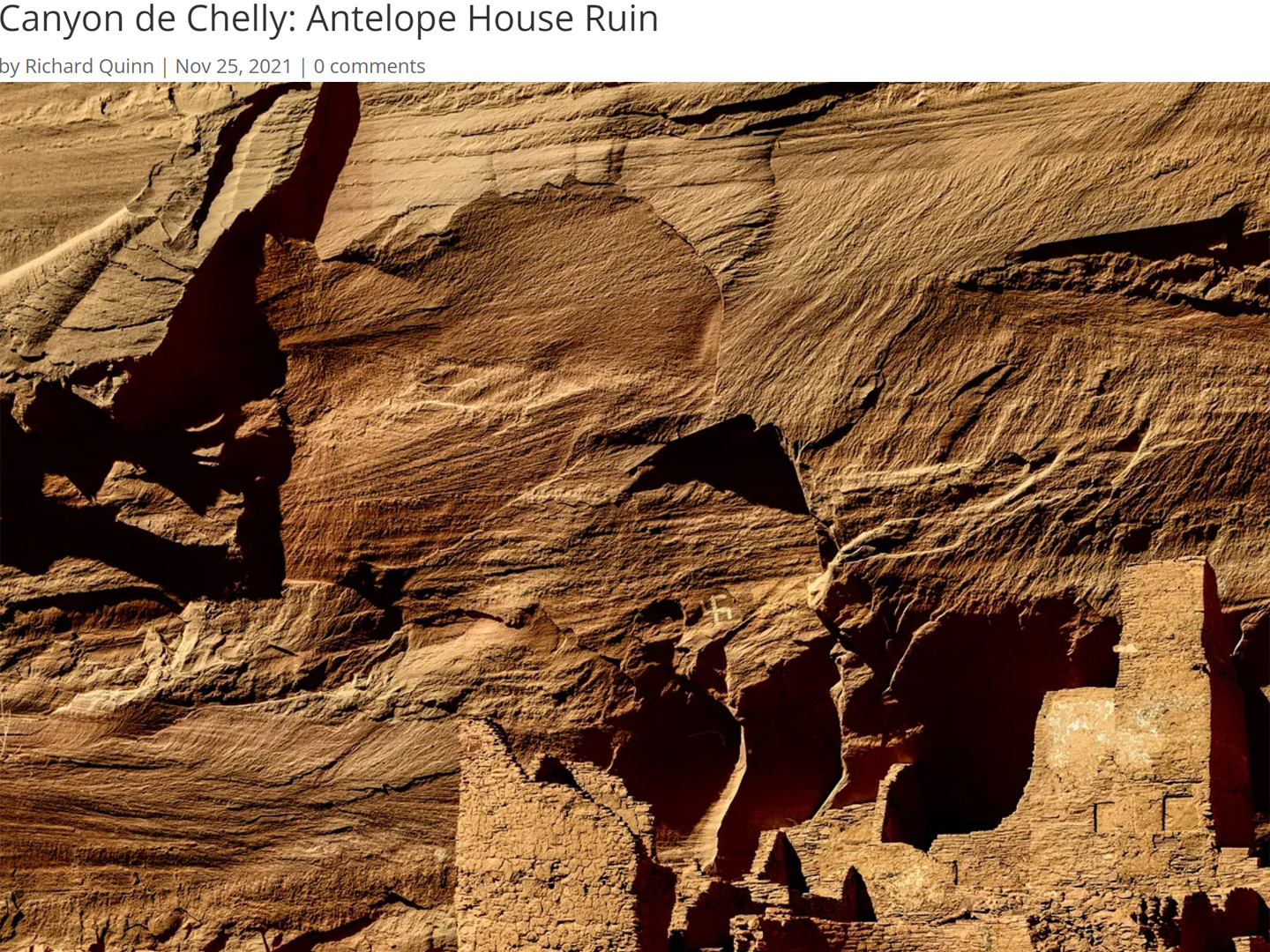

Antelope House

Antelope House was formally excavated in the early 1970’s, by archaeologists working with the National Park Service. Each new culture that occupied this site built atop the remains of their predecessors, so as researchers dug into the stratified foundations, they found the pit houses of the Basket Makers at the bottom, and layers of increasingly sophisticated cultural remains, from the Ancestral Pueblo to the Pueblo people, the Hopi, and the Navajo, each of these groups contributing to the timeline of an area that is exceptionally rich in history.

Of all the ruins and other archaeological sites in Canyon de Chelly, Antelope House is the most thoroughly investigated. That’s at least partially due to simple ease of access: unlike most of the ruins in the canyon, all the primary structures at this site are at ground level.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

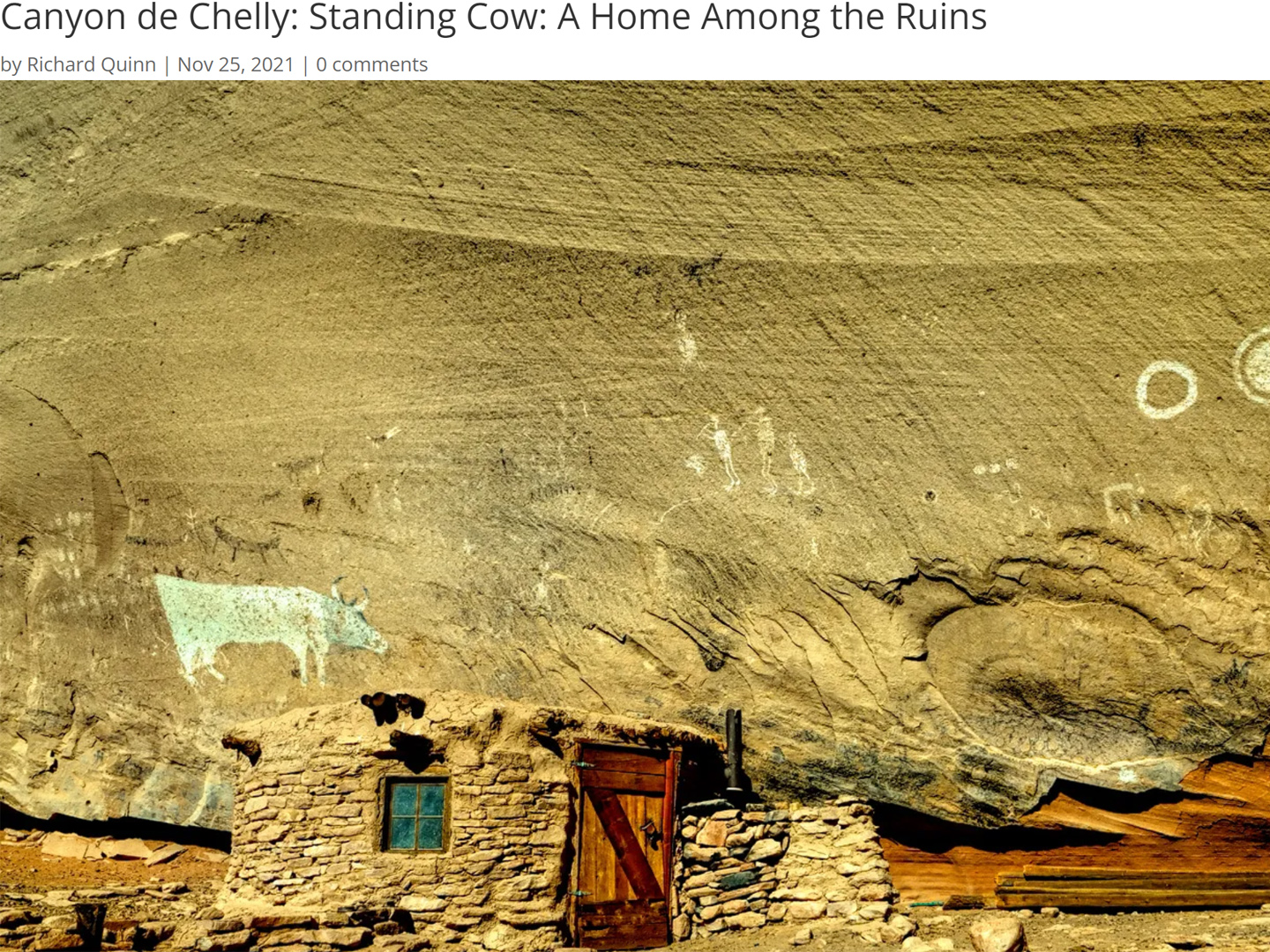

Standing Cow: A Home Among the Ruins

The hogan, much newer than the other structures, was built using sandstone bricks recycled from the surrounding ruins. That would never have been allowed today, but at the time, before the National Monument was established, there weren’t any rules against it, so Sylvia’s great grandfather was simply being practical, using what was available. Today, Standing Cow is on all the maps, as much a part of the human landscape of Canyon de Chelly as the White House and the Mummy Cave. We felt quite privileged to be there with someone who was so directly connected to all of it.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

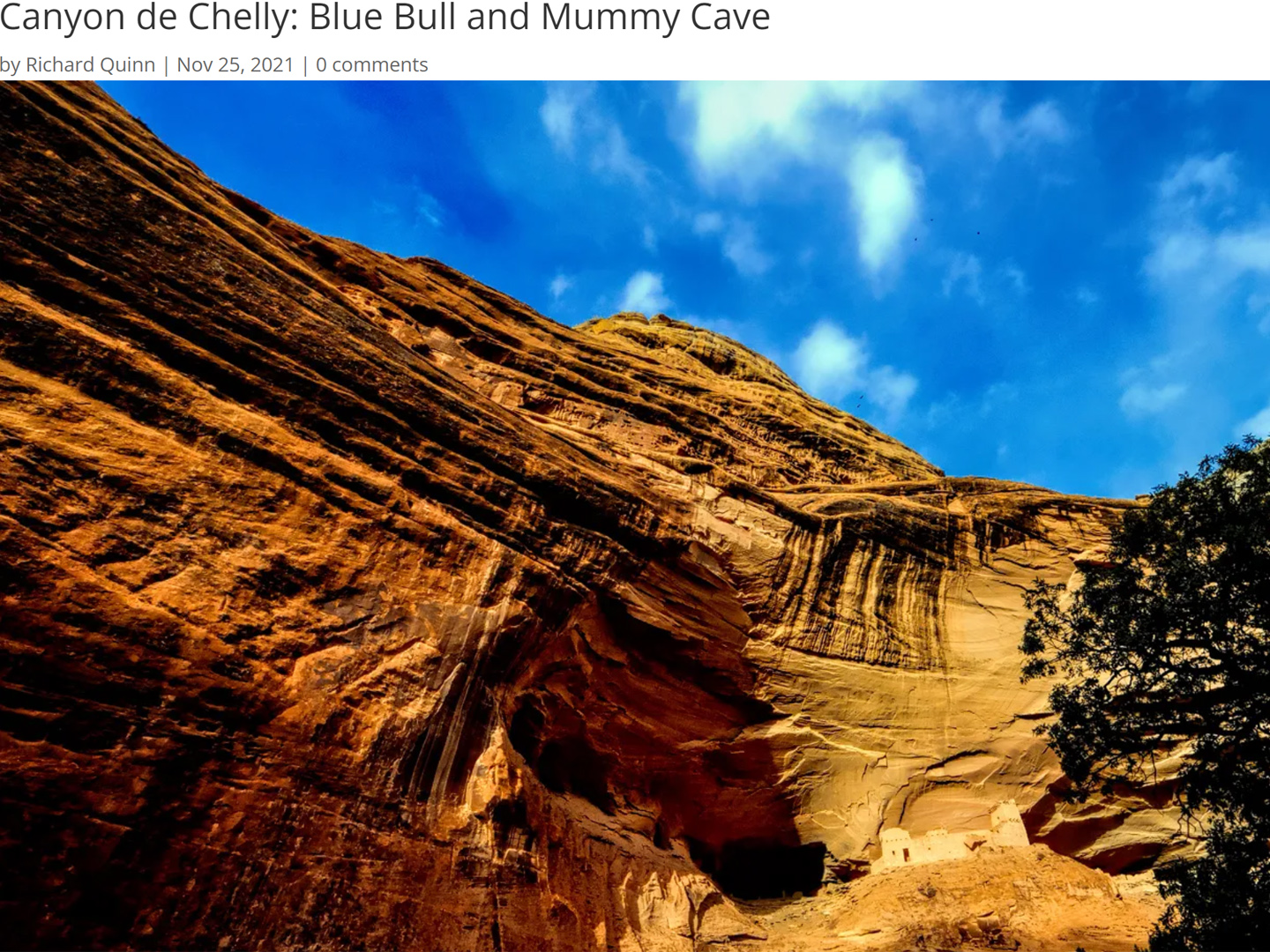

Blue Bull and Mummy Cave

300 feet above the canyon floor, there are two deep alcoves filled with ruins, and on a wide ledge between them, a large, multi-story pueblo, partially reconstructed, and quite impressive. The setting is a natural amphitheater, and the overall aspect of the place is simply stunning.

Occupied for a thousand years, from around 300 A.D. until 1300 A.D. The whole complex, including the main building and the structures in the two flanking alcoves had as many as 70 rooms, including living quarters, ceremonial spaces, and storage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

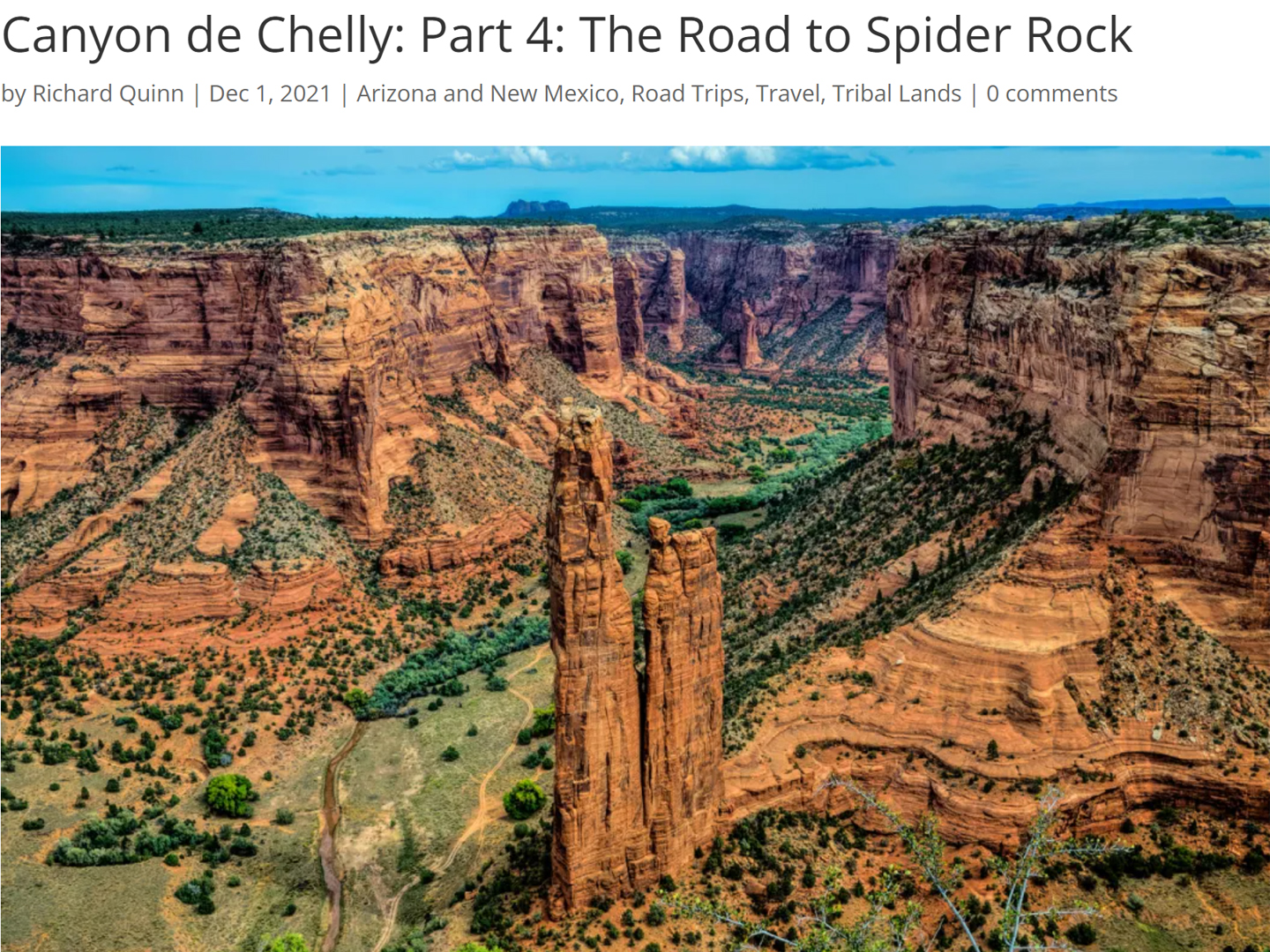

Canyon de Chelly: Part 4: The Road to Spider Rock

Today, only authorized Navajo owned vehicles are allowed inside Canyon de Chelly, but this was in 2013, when it was still possible to drive yourself in your own 4×4, as long as your Navajo guide rode along with you. That arrangement was Sylvia’s specialty, and driving through that canyon, with her ongoing expert narrative providing background on all the points of interest, was some of the best fun I’ve ever had.

The first part of the route was aleady familiar to me. We entered Chinle Wash from that same dirt road, just past the Visitor’s Center, and I took off down the sandy creek bed, keeping up a steady speed and zig-zagging diagonally across the deepest ruts, to avoid getting trapped.

We passed by all the places where we’d stopped the day before, and made it all the way to the junction in just over half an hour. This time, we took the right hand fork, and we hadn’t gone far when we ran into our first big challenge of the day: a steep downslope that crossed a wash, with deep mud at the bottom of the hill.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

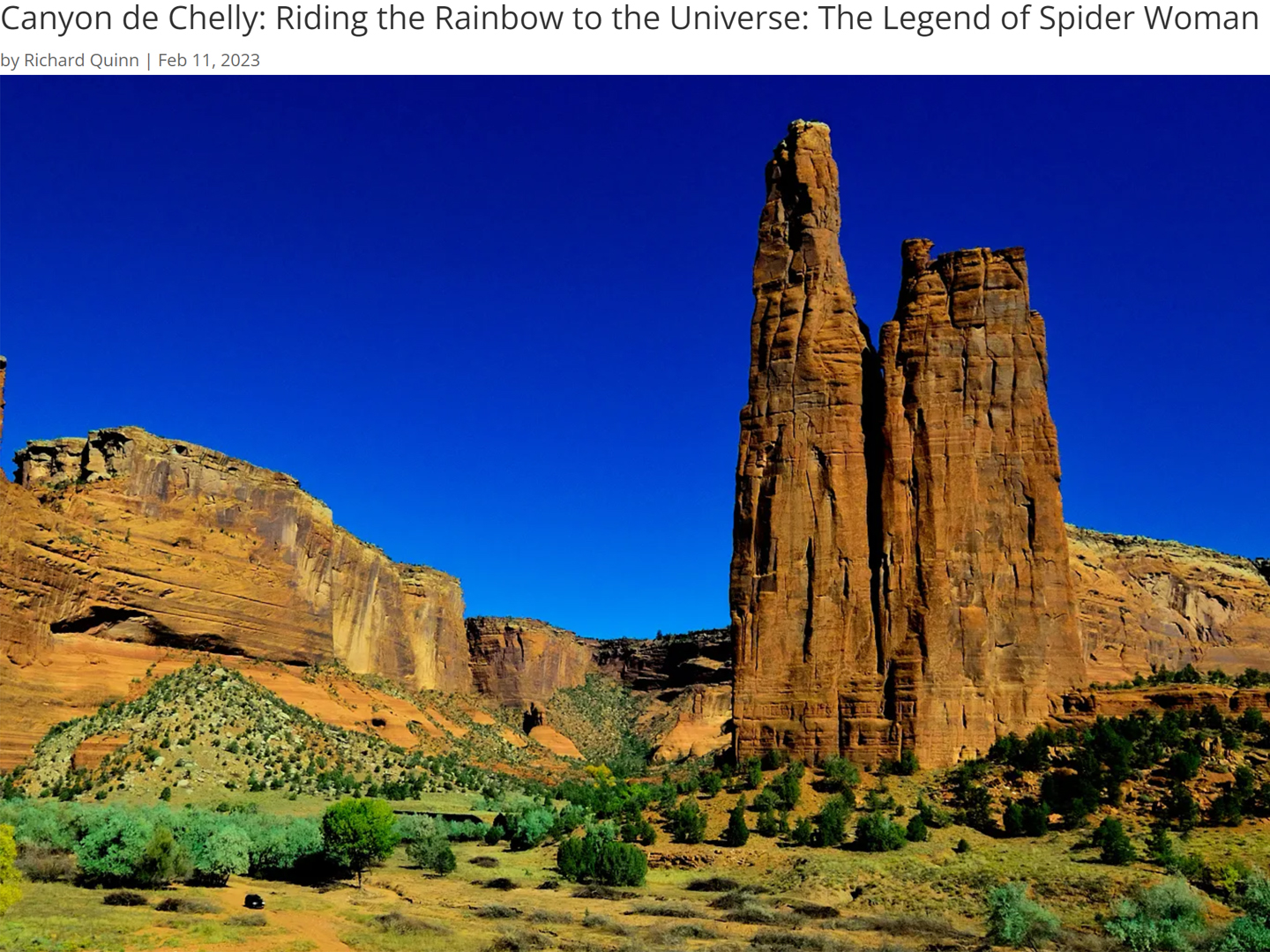

Riding the Rainbow to the Universe

Viewing Spider Rock from below provides a dramatically different perspective on this extraordinary formation. From above, you’re looking down on the whole tableau, and Spider Rock, shorter than the soaring canyon walls, appears as one small part of the larger scene. From below, from the floor of the canyon looking up at it, you can see just how BIG the danged thing is. At 800 feet in height, it’s a good bit taller than your average 50 story sky scraper, and it completely dominates the landscape.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

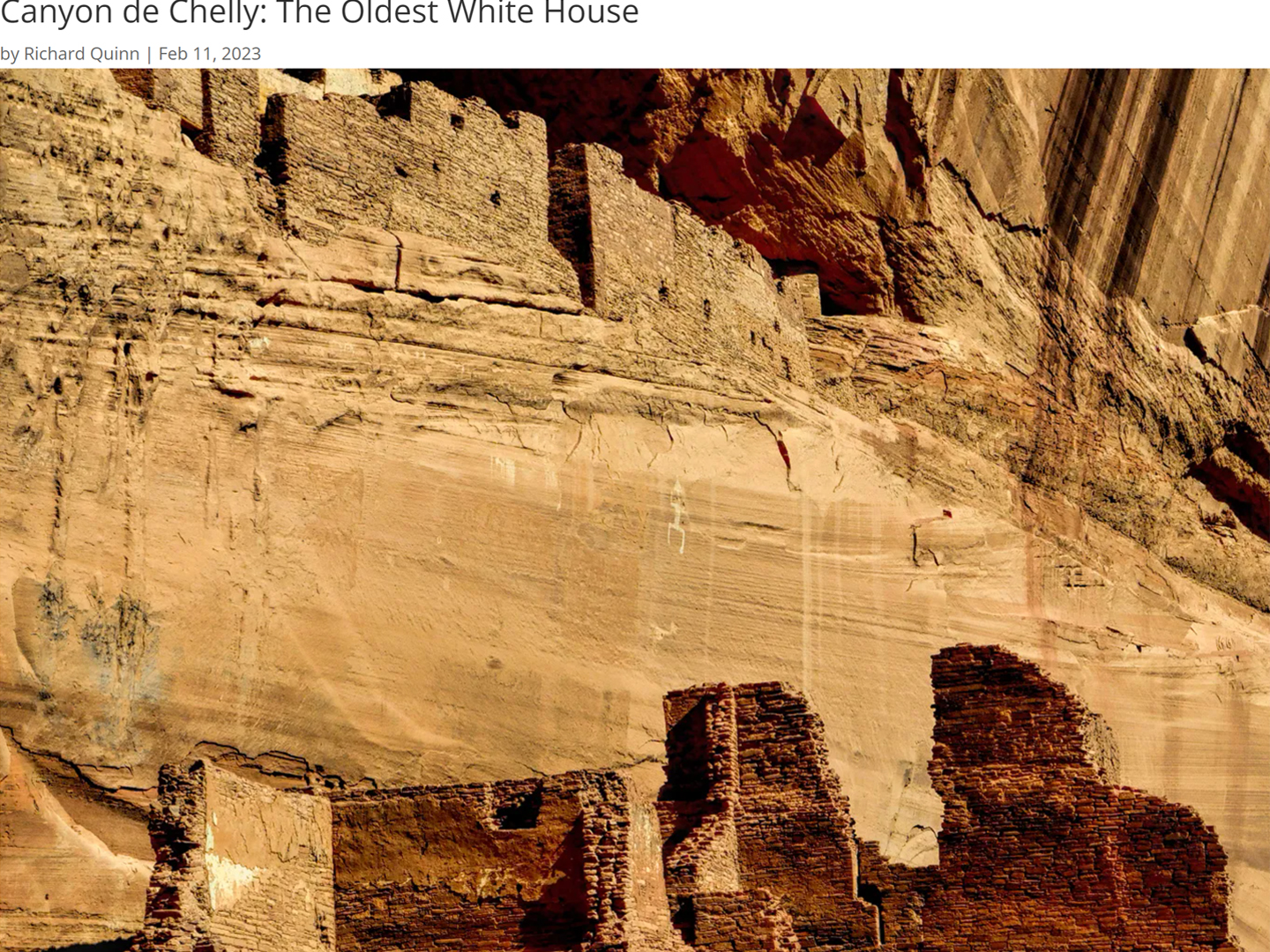

The Oldest White House

At the center of the upper section is a large room, 12 by 20 feet, with a front wall that is 12 feet high and made of stone that is two feet thick. This wall was coated in white plaster, decorated with a yellow band, and it is this white wall, which can still be seen, that inspired the name La Casa Blanca, the White House, to this ancient dwelling that has endured in this place for nearly a thousand years.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY:

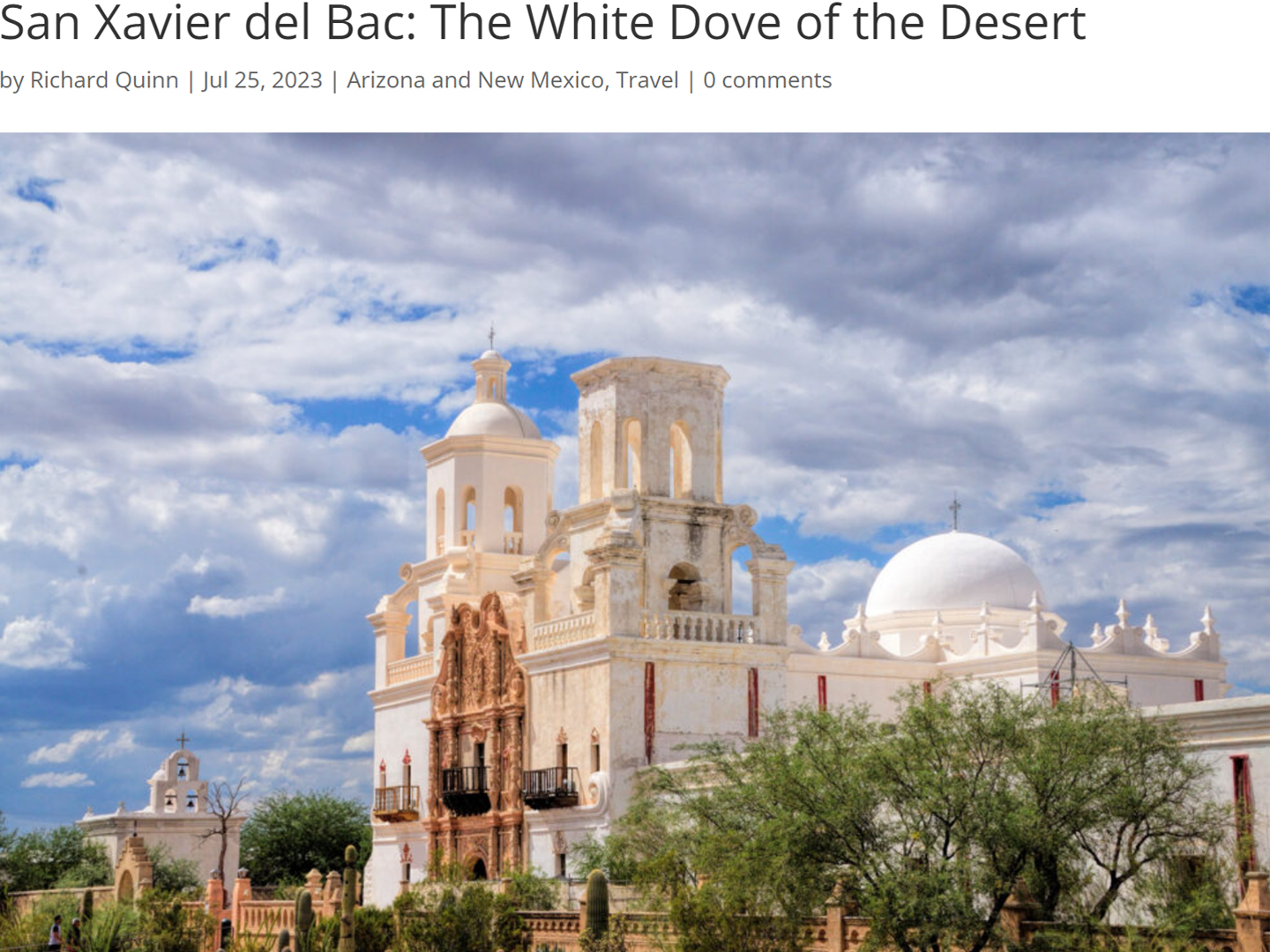

San Xavier del Bac: The White Dove of the Desert

San Xavier has all of the traditional elements of a Spanish Colonial church, along with many others that are quite unique. The craftsmanship of the original building is superb, and features many fascinating details.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A Serendipitous Sunset at Shiprock

I noticed an odd rock formation coming up fast on the left side of the road, almost like a wall built of angular blocks. Shiprock was close, but hidden from view by the wall as I zoomed toward it. After I passed the odd formation, I stole a quick glance in my rearview mirror, and what I saw was a scene so other-wordly, it literally stopped me in my tracks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

ALASKA ROAD TRIP:

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP (IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA):

ARIZONA AND NEW MEXICO:

SOUTH AMERICA:

PHOTOGRAPHY:

0 Comments