Original photographs by

CARL DUISBERG

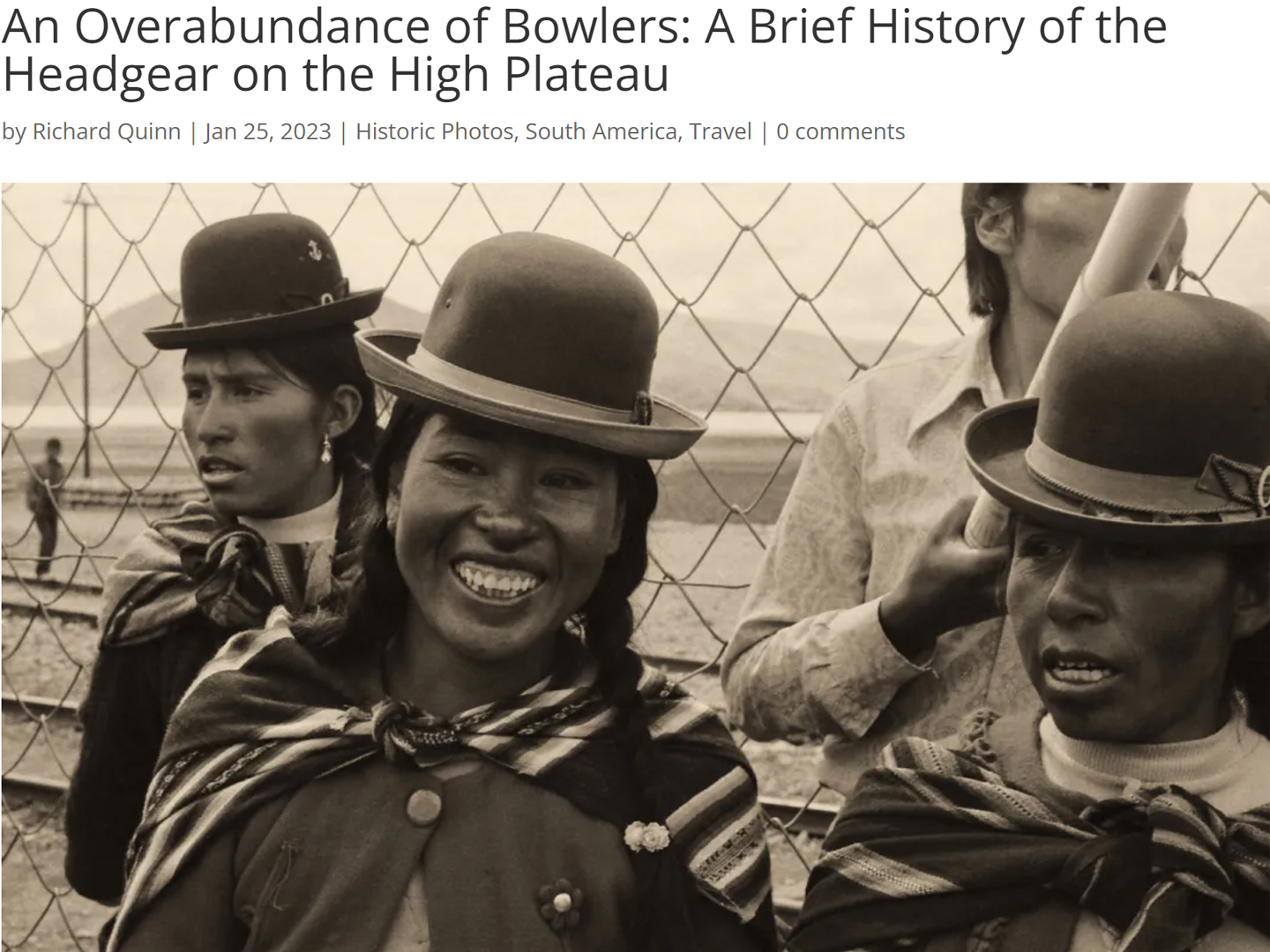

The Bolivian altiplano is a land above the clouds, a high plateau situated between the eastern and western cordilleras of the Bolivian Andes, with an average altitude well in excess of 12,000 feet. There is less oxygen in the atmosphere at such a lofty elevation, but the people who live there have adapted: Andean natives are able to make more efficient use of each breath, so they function just as well at high altitude as the rest of us do at sea level. The altitude has a dramatic effect on the climate as well. It is cold there, all year around, despite the tropical latitude, and the atmospere itself is thinner, so it provides less protection from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. The people have adapted to that by taking a very simple precaution: everyone, almost without exception, wears a hat when they venture outdoors. In every region of the altiplano, every Andean native, from infants to ancients, sports some form of head covering, ranging from shawls to leather helmets to proper English bowlers.

My friend Carl Duisberg traveled throughout this area when he lived in Bolivia, back in the early 1970’s. He’s a very good photographer, and he captured hundreds of candid black and white photographs of villagers in traditional dress. Everywhere he went, the hats were a prominent feature of the local costume. Different ethnic groups, different regions, different hats.

I recently took on the task of restoring and editing Carl’s fifty year old film, and with his gracious permission, I’m sharing a selection of his photos in this post. These historic images are Carl Duisberg’s original work. They are protected by copyright, and may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any photo to expand the image to full screen

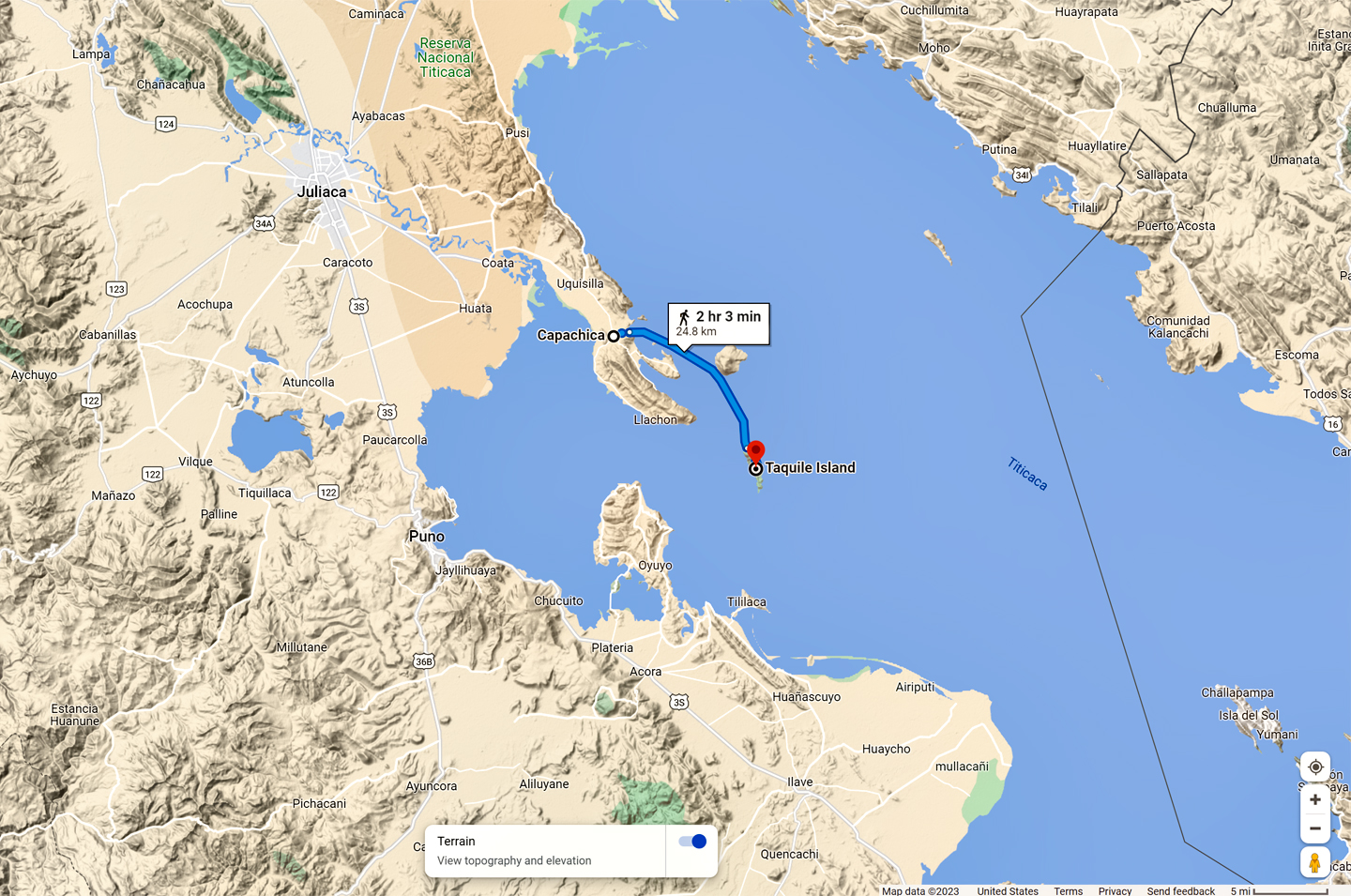

Peru: Taquile Island

Taquile, known in Quechua as Intika, is an island on the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca, 27 miles off shore from the city of Puno. The 2.2 square mile island, which currently has 2,200 Quechua speaking residents, has been inhabited since the time of the Inca by a community of expert weavers. Their traditional skills have been passed down through countless generations, and are still highly valued. In 2005, “Taquile and its Textile Art“ was proclaimed to be one of Unesco’s Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

The men do all of the knitting, while the women spin and dye the wool, using natural pigments derived from plants and minerals. Women also weave the Chumpis, the wide colorful belts that are an important component of local attire.

As for headgear, the men wear traditional tassled caps that they knit for themselves, while the women cover their heads with shawls made from locally produced cloth. The main village on Taquile sits at nearly 13,000 feet, so even though they’re surrounded by water, they have to take the same precautions against the sun as all the other natives of the high plateau.

The only way to get to Taquile Island is by boat, a journey that takes a bit more than two hours. In recent years tourism reached an uncomfortable volume due to unregulated non-resident tour operators flooding the place with day-trippers. The community reacted by establishing their own travel agency, and creating a sustainable tourism model which they control, minimizing the crowds, and keeping the revenue on the island, where it belongs.

These pictures were all taken in 1971, before the first waves of tourists discovered Taquile Island, back when the Taquileños were still an isolated community, a people apart.

Bolivia: the Rooftop of the World

Located in a high valley at almost 12,000 feet, La Paz is the highest of the world’s capitals. 22,000 foot Mount Illimani looms above the city in the background.

This photo was taken in 1971, when La Paz had just over 600,000 inhabitants. During the last 50 years, the population has soared to more than triple that number.

Lake Titicaca, located between Peru and Bolivia on the northwestern edge of the Altiplano, sits at an elevation well above 12,500 feet, which makes it the world’s highest navigable body of water. With a surface area of more than 3200 square miles, it is one of the largest lakes in South America, as well as one of the oldest lakes in the world, having been formed as much as three million years ago.

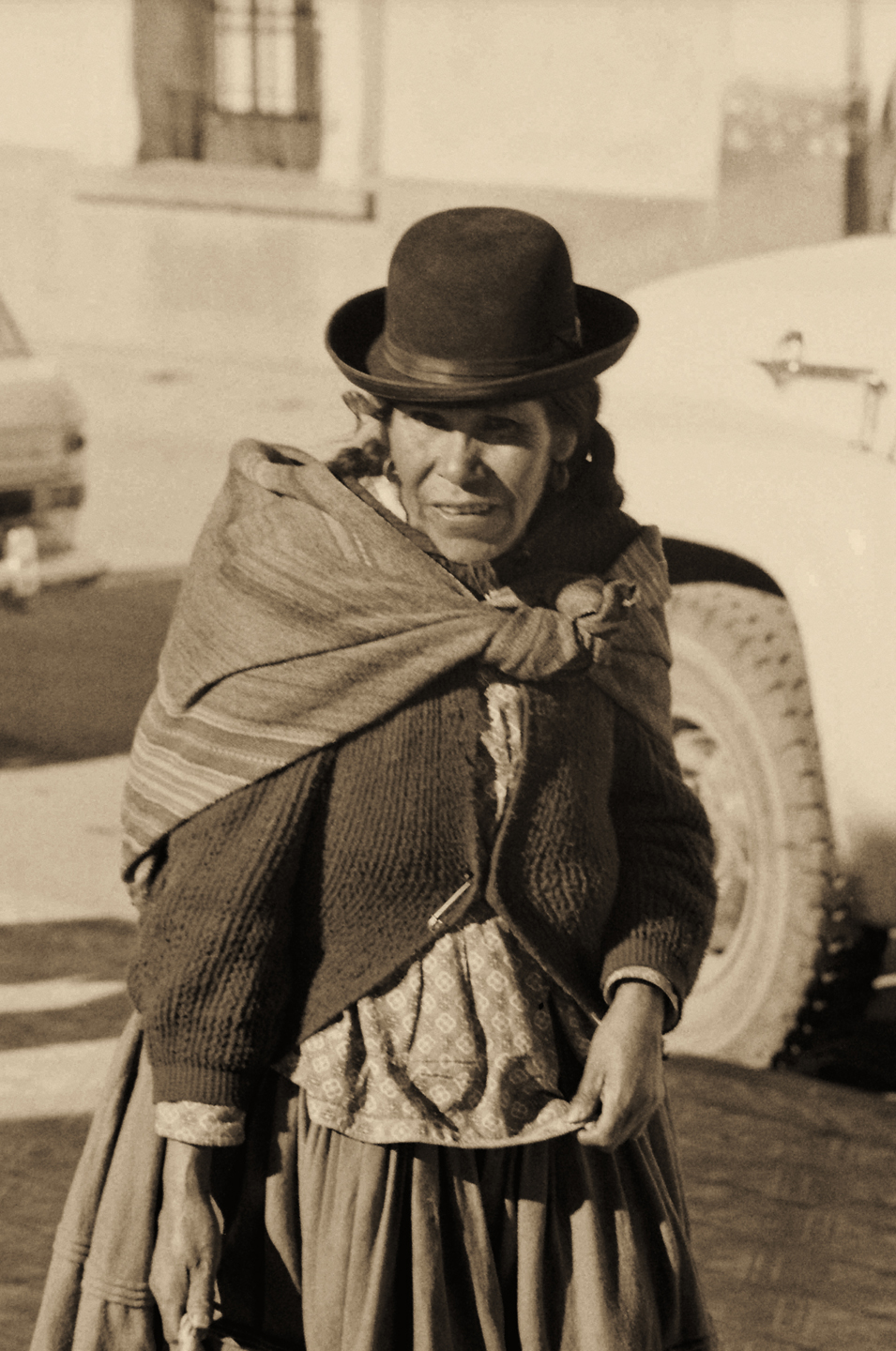

BOWLER HATS:

A Bowler is a hard felt hat with a rounded crown, originally created by London hat-makers Thomas and William Bowler in 1849. Also called a billycock, bob hat, or derby, it is known in Spanish as a Bombin.

So–why do they wear them in Bolivia? And why just the women? As the story goes, during the 1920’s, an English company contracted to supply hats to the men building railroads in Bolivia: bowler hats, which were quite popular at the time. Unfortunately, they miscalculated the size required, and the hats that they shipped were too small to fit the average railroad worker’s head. In a flash of genius, they marketed their overabundant supply of bowlers to native women, by convincing the ladies that they looked wonderfully stylish. To their credit, the style caught on, and it has persisted to this day throughout the Bolivian highlands, as well as in parts of Peru.

POTOSI

In the middle of the 16th Century, a mountain of silver was discovered in the heart of the Andes, in the newly acquired Spanish Colony of Bolivia. The silver and tin deposits were so rich, and the workings so extensive that within a few short decades, the town that sprang up to service the mines and all their workers grew into the largest city in the New World. That city was Potosi, the Pearl in the Spanish Crown, and the greatest source of wealth in all of Spain’s far-flung empire.

With an altitude of 13,420 feet, Potosi is one of the highest cities in the world. It’s still an important mining center, and it’s still growing, with a modern day population of more than 240,000. For the indigenous population of the surrounding area, the mines of Potosi hold terrible memories of harsh, patently unsafe working conditions that cost the lives of far too many young men. But Potosi is also the big town, the place to sell your produce and your livestock, and to barter for your supplies.

These photos, taken half a century ago, show Potosi when it was still caught with one foot in the 19th century. The people pictured are from a variety of nearby communities, as evidenced by the many unique styles of hat!

SUCRE

In 1538, the Spanish founded another new city in their Bolivian Colony, and they called it La Plata, the Silver, in reference to the nearby mines that were the source of the city’s wealth. La Plata was reknowned for it’s beautiful architecture, churches and government buildings and fine houses, all painted white. If Potosi was where the Spanish Dons made their money, La Plata is where they spent it. The slightly lower altitude, a mere 9,200 feet, gave La Plata a more salubrious climate, so most of the upper class in the Bolivian Colony preferred it to Potosi or La Paz.

When the tide of revolution swept through the region, early in the 19th century, Bolivia became an independent country. In 1839, La Plata was chosen to be the official capital of the new Republic, and the name of the city was changed to Sucre, in honor of Jose Antonio de Sucre, the leader of Bolivia’s fight for independence from Spain. Sucre is still the official capital of Bolivia, even though most government functions take place in La Paz.

The Historic City of Sucre has been recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site of unique cultural significance, the best preserved example of Spanish Colonial Architecture still in existence. These photos of Sucre, like all the others in this post, were taken in 1971. The focus is on the native people in the outdoor market—and on their hats! The light-colored hats with the narrow brims and the tall slightly pointed crowns are unique to this part of Bolivia, worn by both the men and the women of a particular village or ethnic group. They appear to be herders, bringing their animals to market.

TARABUCO

Forty miles southeast of Sucre, and a bit deeper into the mountains, you’ll find the village of Tarabuco, home to the Yampara people, and the location of the Tarabuco Market, held every Sunday for the benefit of the local community. Tarabuco is widely recognized as the most authentic indigenous market in Bolivia.

Not that many tourists make it this far, so Tarabuco remains an isolated prize for intrepid travelers, an opportunity to rub shoulders with people living in a world so different from ours that they might just as well be from another planet. (Or at the very least, from another century).

In the pre-Colonial era, the Aymara-speaking Yampara occupied a position in between the more advanced cultures of the altiplano, and the more primitive “bow and arrow” people of the eastern forests and lowlands. As the story goes, they were absorbed into the Inca empire, not through military conquest, rather because of their love of a good party. The Inca Tupac Yupanqui was unable to breach their defenses, so he staged fiestas and offered beautiful women to lure the defenders out of their fortress. Once the party was underway, the wily Inca sent his army forward to capture them.

The distinctive hats worn by the Yampara tell a story, in some cases a tragic tale of loss. The men wear a leather helmet with an embroidered crown and dangling beads decorating the front edge (photo at left); the close-fitting helmets, known as monteras, are styled after the metal helmets of the Spanish Conquistadores.

The women wear their own version of the montera, called a pacha montera, with a wide, upswept brim and extensive embroidery on the top (Photo in the middle).

When a woman’s husband dies, she gives up her pacha montera, and puts on his manly helmet, to signify that she has assumed his responsibilities in the community. The photo on the right is a graphic demonstration of this custom. The man’s helmet, perched atop this young widow’s head, clearly weighs upon her. (Click photos to expand)

I’d like to thank Carl one more time for the use of his pictures. They provide a unique window into a bygone era, capturing a world and a way of life that, quite frankly, no longer exists. These photographs are important, historically, ethnographically, and artistically. I’m grateful for having had the opportunity to work with them, and I’m proud to display them here.

If you’ve enjoyed seeing these historic photos, check out the rest of the series:

Portraits of a People, Lost in Time;

Puno Day Festival: A Centuries-Old Tradition on the Shores of Lake Titicaca;

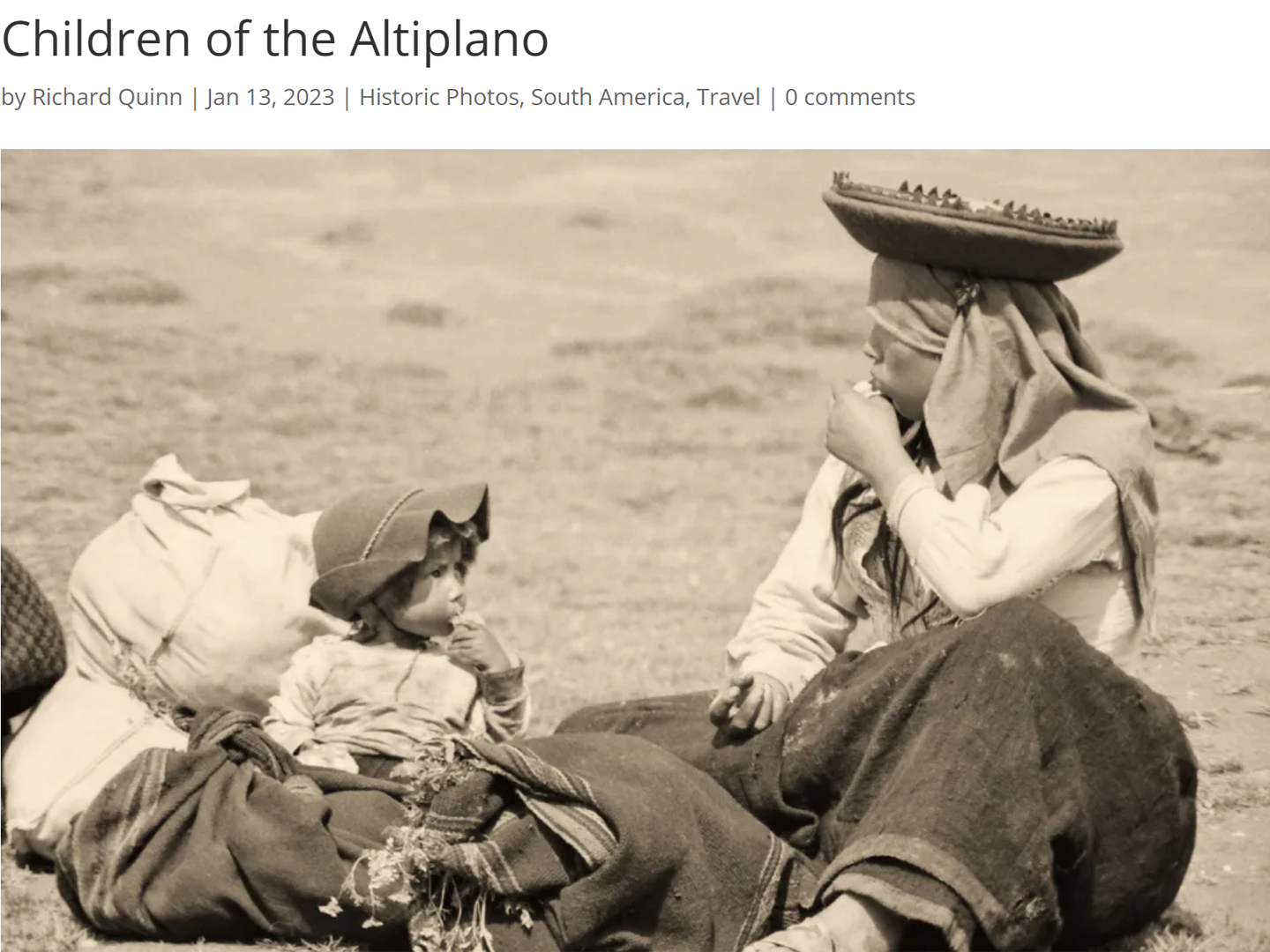

Children of the Altiplano; and

Chinchero: The Place Where Rainbows are Born;

READ MORE LIKE THIS

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

Long Ago and Far Away: South America in the Early 1970's

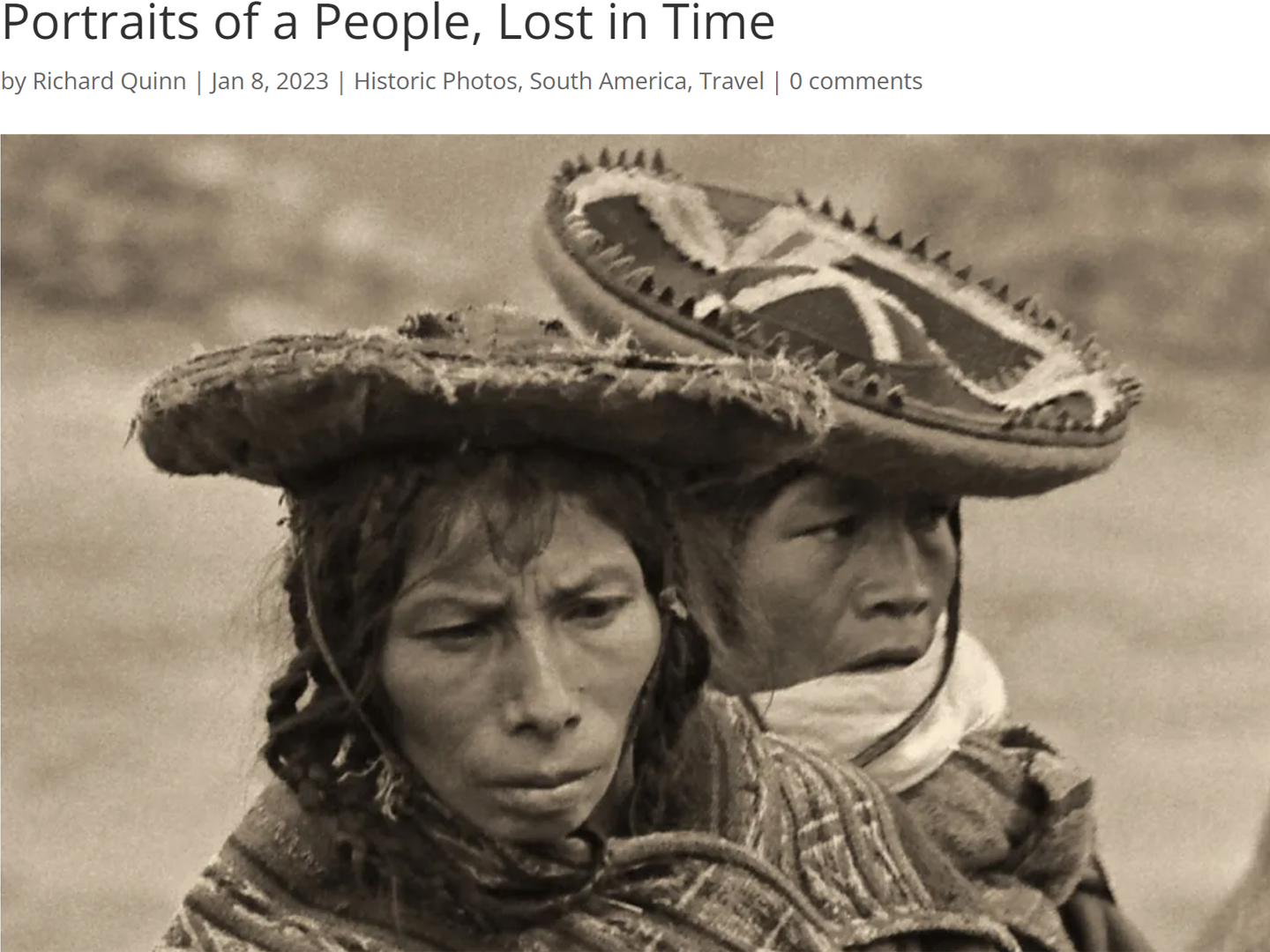

Portraits of a People, Lost in Time

50 year old portraits of Andean natives in their traditional dress, taken in mountain villages not yet tainted by outside influences.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Puno Day Festival

Historic photos of Peru's Puno Day festival, taken in 1971. Included is the reenactment of the birth of the Inca empire on the shore of Lake Titicaca, with costumed dancers lining the streets of Puno.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Chinchero: The Place Where Rainbows are Born

Candid portraits of villagers in traditional dress, taken in Chinchero, Peru in 1971, before the outside world intruded.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

An Overabundance of Bowlers: A Brief History of Headgear on the High Plateau

Andean natives have adapted to the intensity of the high altitude sun by taking a very simple precaution: everyone, almost without exception, wears a hat when they venture outdoors.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Rape of Bahia Concha

It was the Tairona gold that triggered a blood lust in the Spanish invaders, ultimately causing the destruction of the entire Tairona civilization. That cycle was repeated in modern times, when the lust for Tairona gold infected the guaqueros, causing the destruction of the last refuge of the Tairona ancestors, in one final humiliation, one last indignity: the RAPE of Bahia Concha!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Tairona Gold: The Curse of the Coiled Serpent

Paul dug with his hands then, finally sticking his arm into a hollow space, pulling out a dark object. Grinning at me from the bottom of his hole, he handed up what he’d found. A round blackware vessel representing a coiled serpent, open in the middle, with a spout at the top of the head. I’d seen a lot of Tairona artifacts, but I’d never seen anything remotely like that one.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

In the Vale of the Stone Monkeys: Peril and Petroglyphs in the Colombian Jungle

El Manco was easy to spot; he had embraced his defining handicap, a right arm that had been severed above the elbow, and that wasn’t even his only problem. He was also missing his right eye, nothing there but an empty socket and an ugly knot of scar tissue. “Tough old bird” doesn’t begin to describe a hardscrabble character like Manco; he had a face with creases like a roadmap straight to his own personal version of hell.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

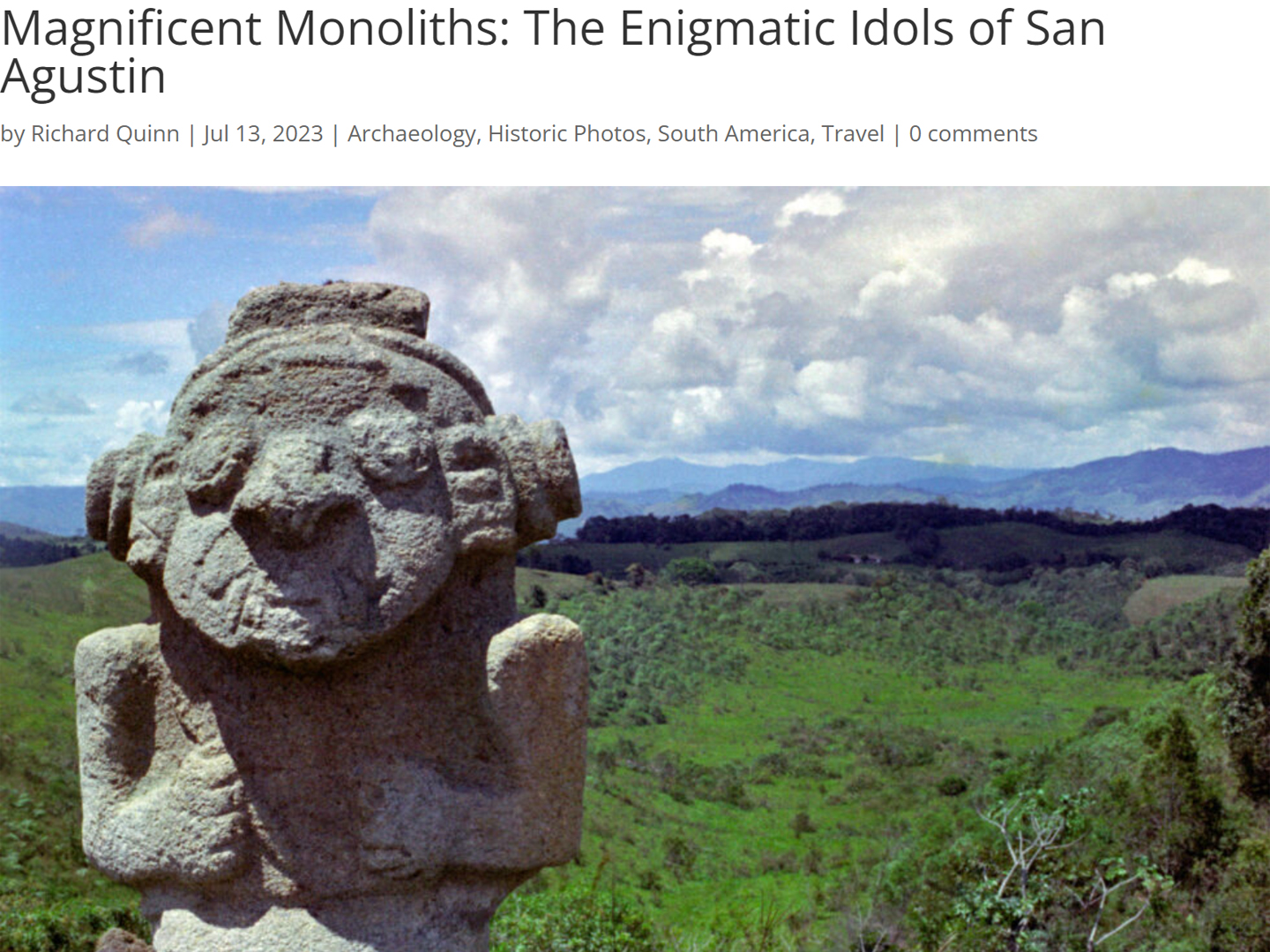

Magnificent Monoliths: The Enigmatic Idols of San Agustin

At least 200 monolithic statues are preserved within the boundaries of the San Agustin Archaeological Park, along with 20 monumental burial mounds. Each statue is unique, but taken as a group they provide a fascinating overview of the rituals and beliefs of one of the earliest complex societies in the Americas. The enigmatic idols of San Agustin are truly unmatched among the world’s ancient monuments.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

There's nothing like a good road trip. Whether you're flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you're out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who's never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments