What do you call it when you stumble across something wonderful that you didn’t know anything about in advance? Some people say that’s just good old-fashioned luck, while folks that are a bit more full of themselves tend to consider it fate, or destiny. Myself, I’m partial to the notion of serendipity: by definition, “an accidental discovery.” When I travel on my own, especially when it’s to someplace new, I rarely make any detailed plans beforehand. I usually prefer to figure out the specifics as I go along, and the reason for that is my abiding love for the joy of pleasant surprise. I like to make a point of leaving myself open for the unexpected. For Serendipity.

I’ll give you a prime example: back in 2016, I was traveling through northern Arizona, researching obscure highways for my Road Trip book: Arizona and New Mexico: 25 Scenic Sidetrips. I stopped in Second Mesa, on the Hopi Reservation, to check in with my friend Joe Day at the Tsakurshovi Trading Post. (This was a few years before Joe and his wife Janice retired and closed their shop). I was on my way to Farmington that day, and since Joe knew the area better than anybody, I asked him if there were any particularly scenic roads that might be good alternatives to the main highway.

“Are you going straight east to Gallup?” he asked me. “Or were you going north first, past Canyon de Chelly?”

“I wouldn’t mind going past Canyon de Chelly,” I said. “I won’t have time to stop, but I love the area.”

“Here’s what you should do,” said Joe, rummaging behind the counter for a map. (A well-worn copy of Indian Country, a detailed map of the Four Corners region put out by AAA, and highly recommended). “We’re here,” he went on, stabbing a finger at Second Mesa, then tracing along the curvy line of State Route 264. “Go east to 191, then north to Chinle. You know the road that follows the North Rim of Canyon de Chelly?”

“Sure. The one that ends at the Mummy Cave Overlook.”

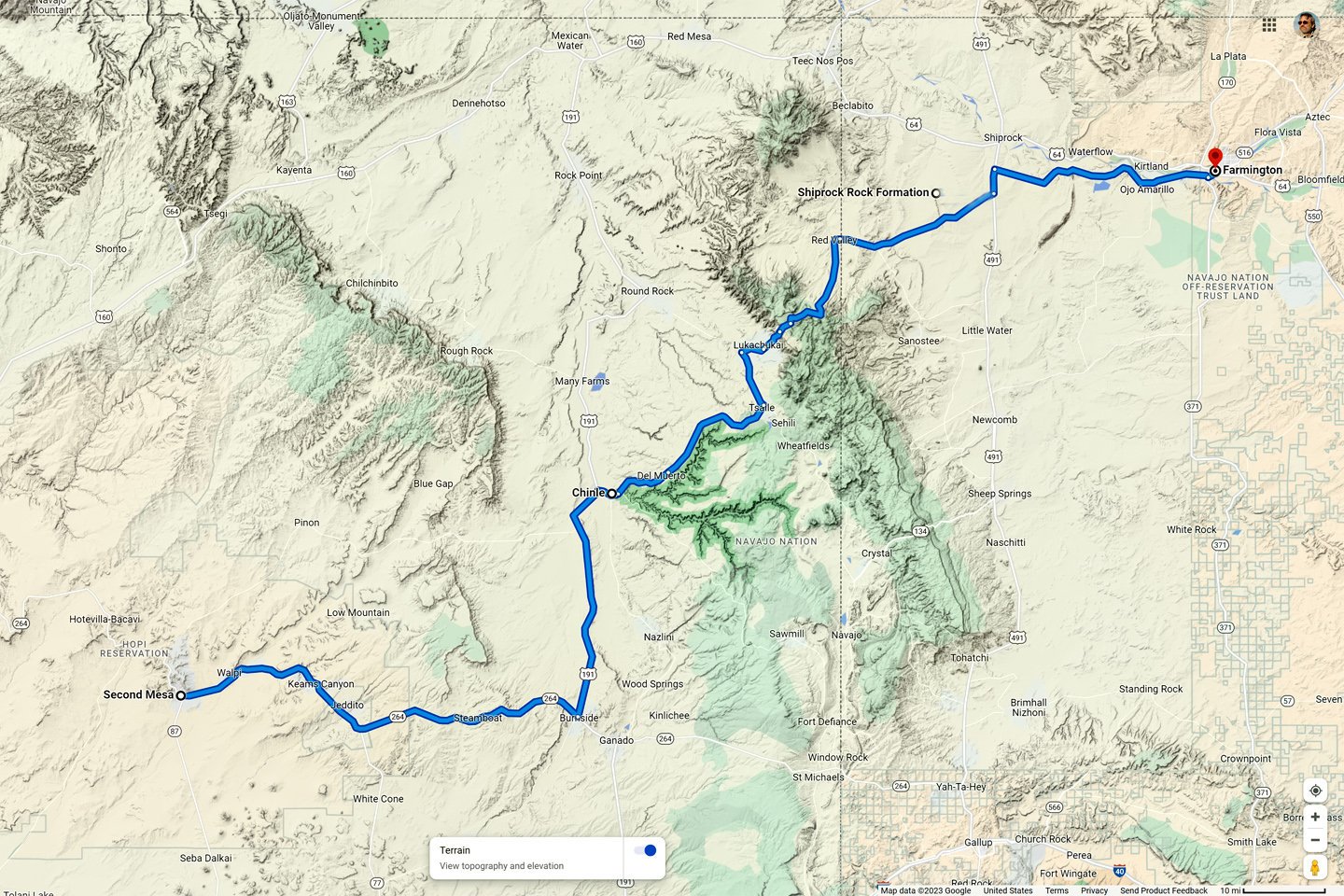

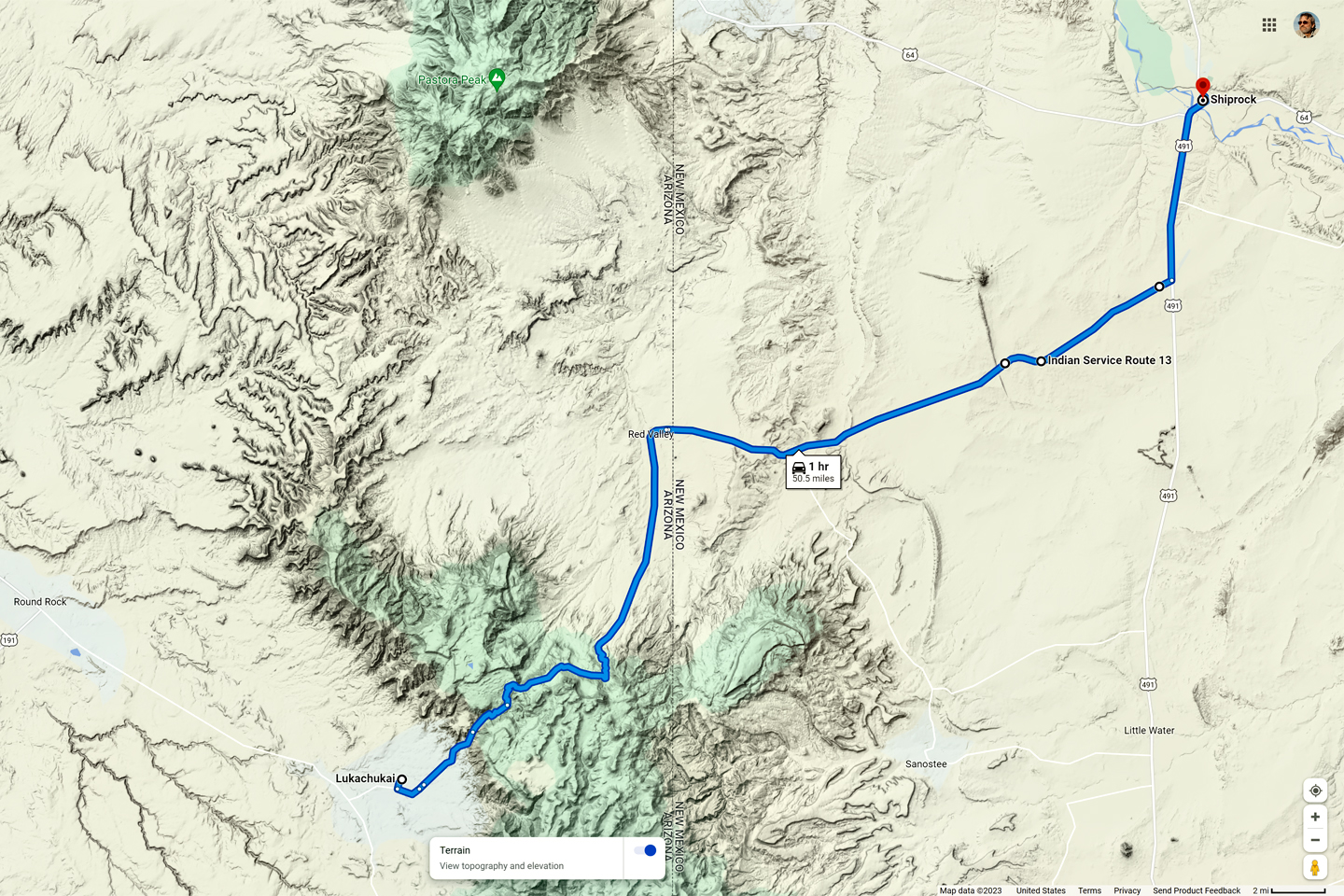

“Right,” said Joe. “But it doesn’t end at the Overlook. You’ll want to keep going on that road, Route 64, until you get to Tsaile, where it intersects Navajo Route 12.” He pointed out the junction on the map, then traced his finger north. “Head toward Round Rock, but look sharp on your right, and after a few miles you’ll take the turnoff for Route 13, the road to Lukachukai. Go through the town, then stay on Route 13 up and over the pass at the top of the mountains. There’s red rock, pine forest. and great views. You’ll come down the other side, near the New Mexico state line, close to Shiprock, and from there, Farmington is a hop and a skip.”

Route from Second Mesa to Shiprock

“Is it paved? Or will I be glad I’m driving a Jeep?”

“It’s a good road,” Joe assured me. “There’s a gas field in the Lukachukais. They had to upgrade the road to get the trucks and equipment up there.”

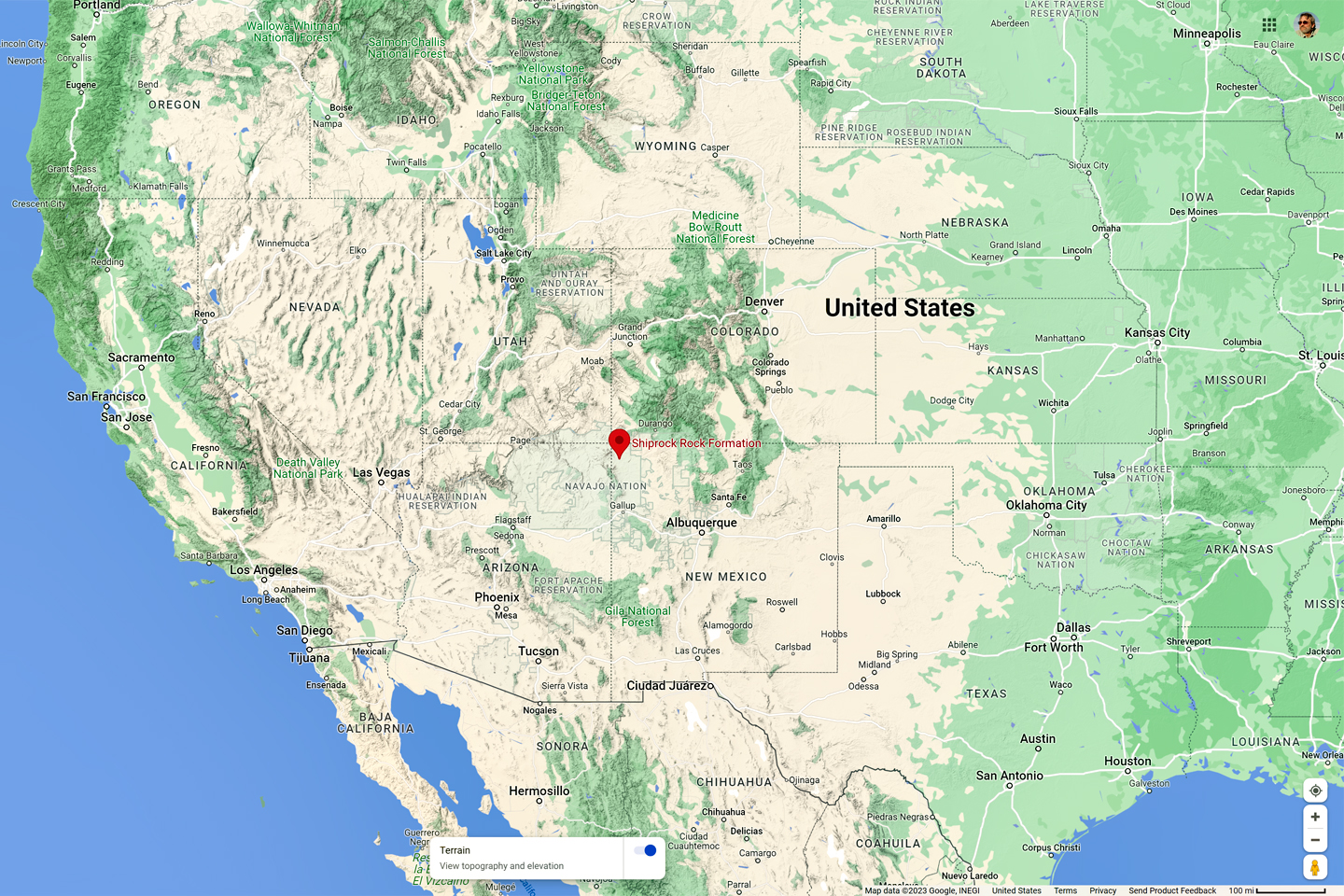

Shiprock, in relation to the Western United States

Joe pretty much had me when he mentioned Shiprock. I knew it was a volcanic formation of some sort, but that was all I knew. I’d never been in that part of New Mexico, so I’d never seen it for myself, and I wasn’t sure if it was worth including in my book. Looking at Joe’s map, it was obvious that I’d be passing close to it. Maybe I’d get a nice view of the peak from a distance, coming down off the mountains. And, there was an added bonus: this route was actually a shortcut!

Shiprock location, in relation to the Navajo Nation

Shiprock location, in relation to Navajo Route 13

I had an uneventful drive from Second Mesa to Chinle, the gateway to Canyon de Chelly National Monument. That’s a place I know quite well, one of my favorites in all the world, so it seemed quite strange to be driving through the area with no plans to stop. I passed through the town, and when I reached the National Monument Visitor’s Center, I took the left hand fork, onto Route 64, the North Rim Drive. That road, which I’d driven many times, leads to several overlooks offering views into Canyon del Muerto. In the past, I’d always turned around at the last of these, the Mummy Cave Overlook. This time I kept going, and just as Joe said, I ended up in Tsaile, at the intersection with Navajo Route 12.

Click Maps and Photos for an expanded view.

Lukachukai Red Rocks, along Navajo Service Route 13

After driving north for a few miles, I reached the turnoff for Lukachukai, and, following Joe’s instructions, I headed off on Navajo Route 13. Just as he’d promised, it was a very pretty drive, along a good road lined with red rock cliffs. A series of short switchbacks took me higher, through scrubby piñons into an actual pine forest. I had no clue that these mountains were high enough to accommodate a forest, but there it was, and Joe was right about the gas field, also. There were dozens of side roads posted with signs, but at that time of day, there were no workers anywhere about, and no other vehicles coming from either direction.

I made it to 8,000 foot Buffalo Pass, the high point of the road, and started down the other side. It was getting late in the day, so there were long shadows spilling across the landscape. From that vantage point, everything I was seeing was in New Mexico, including a distant formation that was very obviously Shiprock.

I’m not sure what I was expecting, but from there, from so far away, it wasn’t particularly impressive. There was good light on the scene from the lowering sun, but there was a fair bit of dust in the air, so Shiprock was all but lost in the haze.

The formation stood more or less alone, rising up from a level plateau, but it was impossible to tell how big it was, because there was nothing around it to lend a sense of scale. All in all, I was disappointed, because this was hardly the dramatic perspective I was hoping to find.

Shiprock, as seen from Navajo Route 13, coming down on the east side of the Lukachukais after cresting Buffalo Pass:

As I descended the mountains, I stopped a few times to focus on the formation with my telephoto lens. That brought the peak closer, and the setting sun added some nice contrasting shadows. The sun was dropping fast, and it was beginning to look like these distant photos were the best I was going to get. I figured that by the time I got down there on the flat, close enough to really SEE Shiprock, there wasn’t going to be any daylight left to see it by. I used my zoom to blow the thing up as big as I could get it, snapped one last frame, and set my camera on the seat beside me, pretty sure that I was done taking pictures for that particular day.

Shiprock from a distance, like a stone ship under sail

Once I got down to flat ground I was able to move a little faster. I don’t much like being out on those empty roads after dark, so I focused on making time. I passed through the tiny community of Red Valley, where the road curved to the east. From there, it was pretty much a straight shot to US 491, which is a larger highway. I figured if I could make it that far before it got full dark, I’d be in good shape, so I put my pedal to the metal, and kept my eyes focused on the road ahead, looking out for wildlife or any other hazards in the darkening landscape. Shiprock was there, off to my left, but I wasn’t paying much attention to it, figuring it was already too dark for photos.

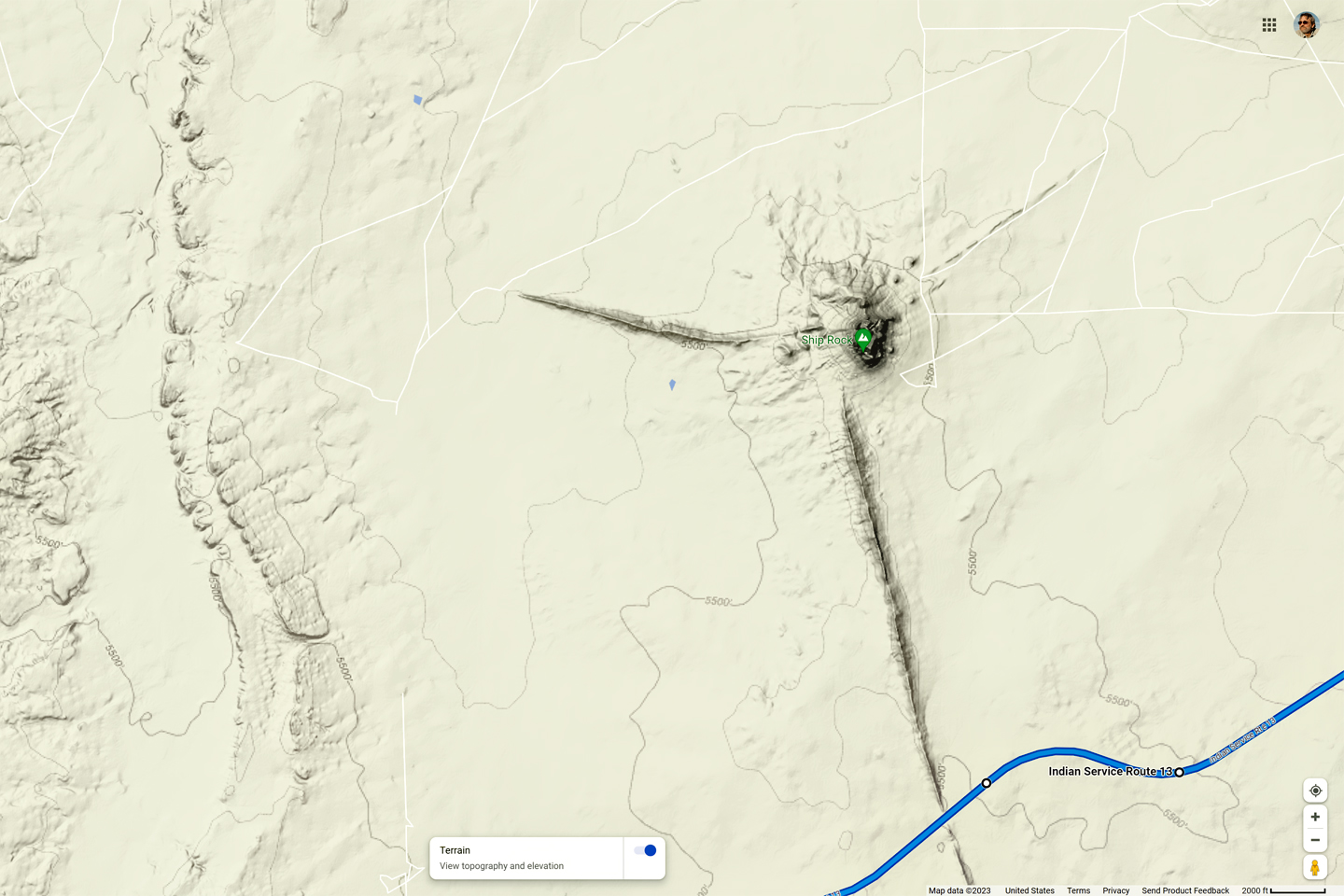

I was probably doing close to 70, a bit too fast for that stretch of road, especially in the half-dusk. The sun was on the far side of the Lukachukais, so once it dropped below the ridgeline, the whole world was in shadow, earth and sky in shades of gray, getting darker by the minute. I noticed an odd rock formation coming up fast on the left side of the road, almost like a wall built of angular blocks.

Photo © Google Street View, edited to simulate the scene as described

Shiprock was close, but hidden from view by the rock wall as I zoomed toward it. After I passed the odd formation, I stole a quick glance in my rearview mirror, and what I saw was a scene so other-wordly, it literally stopped me in my tracks:

Photo © Google Street View, edited to simulate the scene as described

I screeched to a halt and flipped a quick U-turn, then sped back to a side road that ran parallel to that wall of rock. I parked and jumped out, and right at that moment, the sky brightened with an orange hue, the last gasp of daylight. I had about 30 seconds to click off half a dozen hand-held frames before the last trace of color faded from the sky.

This was it–my “Quinn-tessential” Shiprock Sunset shot, and it couldn’t have been more perfectly timed. Truth be told, at the moment when I took the picture, I didn’t even know what I was shooting, because the “wall” that added so much to the composition was still a complete mystery. One thing was certain: it wasn’t planning that got me that shot. It was my old friend, Serendipity.

A week or two later, I was consolidating my notes from that trip, and editing some of the pictures. That’s when I finally did my research, and found out just what the heck it was that I’d stumbled across.

The rock wall that intersects Navajo Route 13 at that spot is known as a lava dike. Some 27 million years ago, the formation we now call Shiprock lay deep within the throat of a volcano that exploded, opening cracks in the earth that radiated from the crater like the spokes of a wheel. Magma filled the cracks, cooled, and solidified into rock. Over the eons, the bulk of the extinct volcano eroded away, along with most of the surrounding plateau, exposing that plug of harder rock from its core and the hardened magma that had filled those cracks.

The 1600 foot tall Shiprock formation is sacred to the Navajo, and it’s off limits to outsiders, expecially rock climbers. There are roads that take you closer, but they’re all on private property, and it would be disrespectful (as well as illegal) to drive on those roads without permission. The Navajo name for the peak is Tsé Bitʼaʼí, “Rock with Wings,” in reference to the radiating lava dikes.

Click any photo to stop the slides from advancing and expand the images to full screen.

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY:

(This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.)

A Sunset at White Sands

Dropping down out of the Sacramento Mountains near Alamogordo, the sky was filled with the colors of the widest rainbow I’ve ever seen. Down on the flat, another rainbow came spearing down through the clouds before setting out in pursuit of a downpour, off in the middle distance.

New Mexico's Golden Autumn

When you think of autumn foliage, the list of places that comes to mind is much more likely to include New England than New Mexico--but the Land of Enchantment is full of fall surprises!

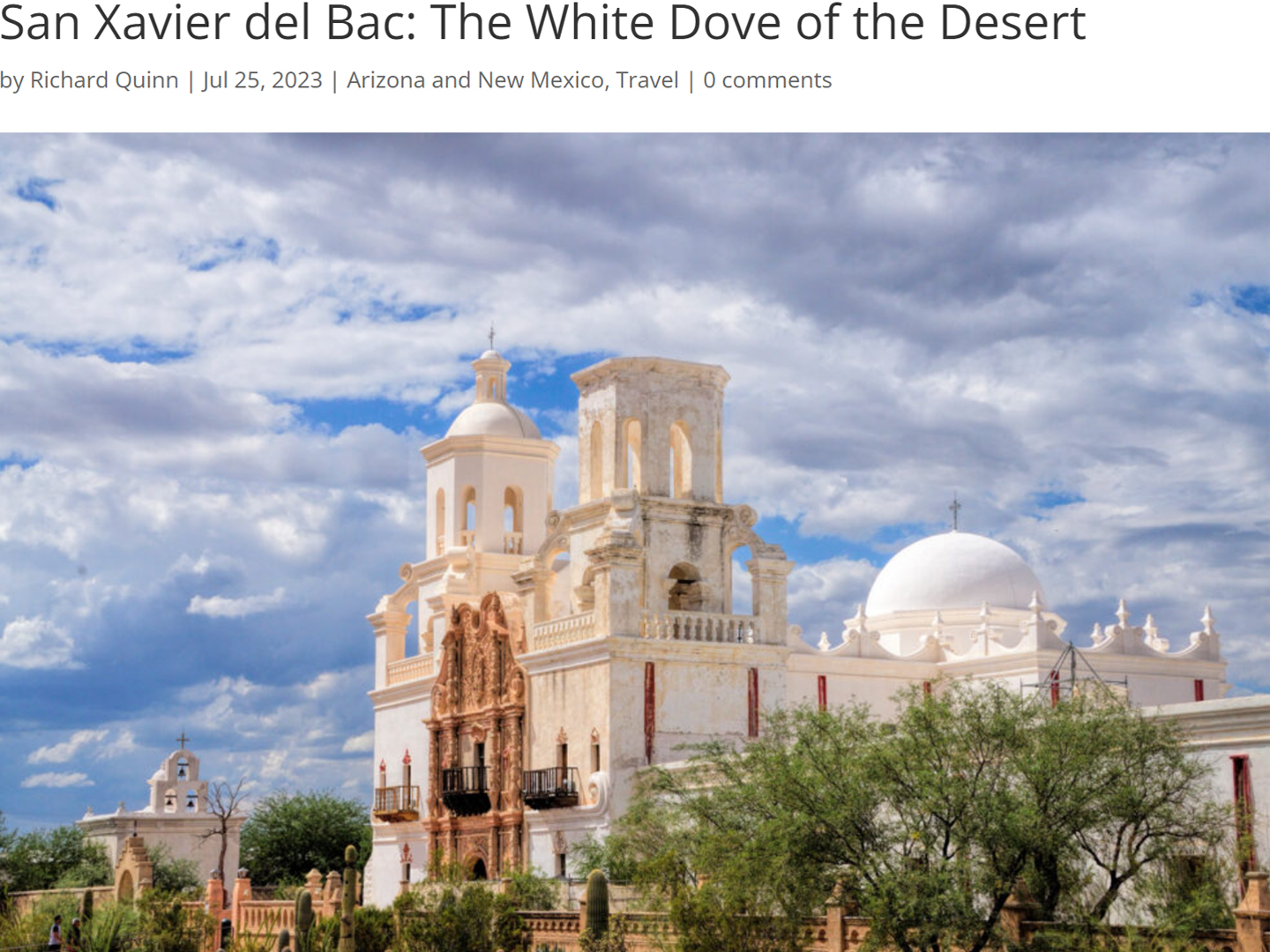

San Xavier del Bac: The White Dove of the Desert

San Xavier has all of the traditional elements of a Spanish Colonial church, along with many others that are quite unique. The craftsmanship of the original building is superb, and features many fascinating details.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

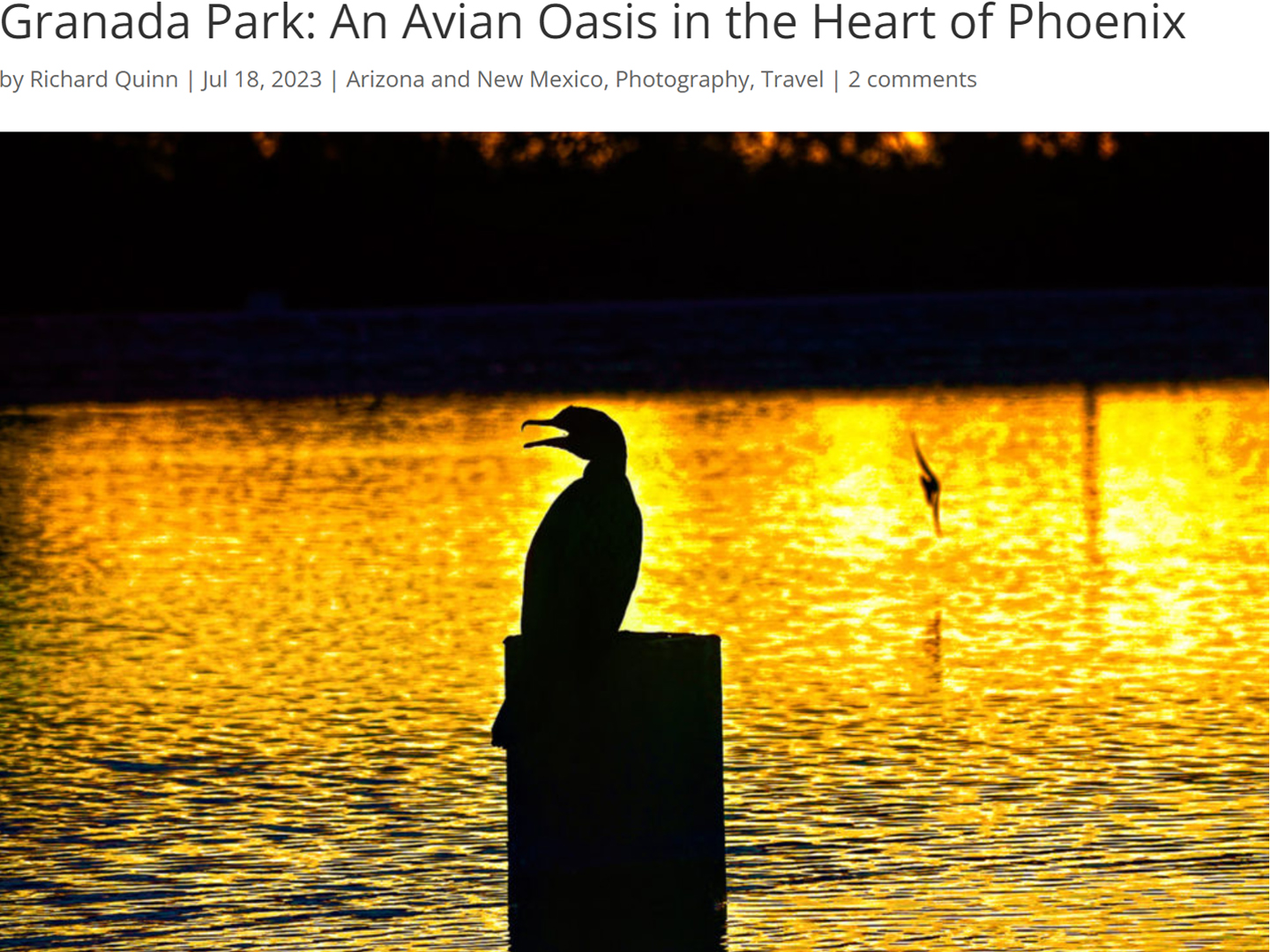

Granada Park: An Avian Oasis in the Heart of Phoenix

Granada Park is a Phoenix City Park that’s adjacent to a popular Mountain Preserve. Its location, along with certain other advantages, make it unique in some very specal ways.

The Incomparable Beauty of Antelope Canyon

Antelope Canyon: Part 1

Slot canyons are formed, over the course of many thousands of years, when torrents of rainwater borne from the monsoon storms of summer sluice through channels and cracks in the soft sandstone. Powerful floods strike repeatedly, carving narrow, twisting pathways into the cross-bedded layers of rock, sculpting swirling formations that look like petrified waves.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Antelope Canyon: Conjuring a Beam of Light

Ephemeral “God beams” appear like magic in the confined space, slanting across the canyon floor like spotlights on a theater stage, only to disappear after a few minutes as the earth spins another fraction of a degree, breaking the perfect alignment.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Antelope Canyon: Conjuring a Beam of Light: Take 2

Today, thanks to Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook, and all the other photo sharing sites out there, every human on the face of the earth knows about Antelope Canyon, and the volume of visitors has mushroomed into the millions. Instagram, alas, is its own worst enemy,

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Most Beautiful Place on Earth:

A Guide to Canyon de Chelly National Monument

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the pictures to open the pages.

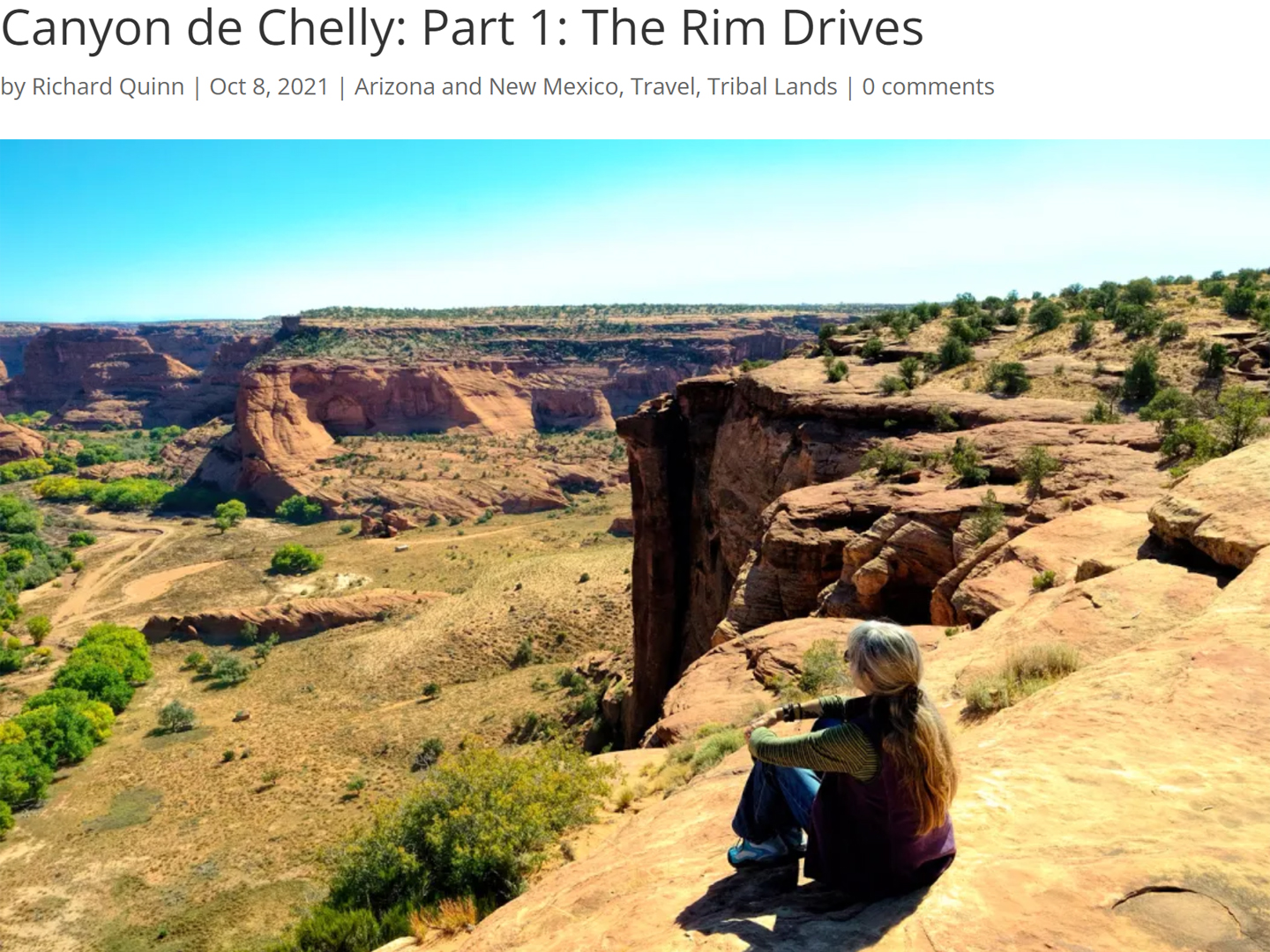

Canyon de Chelly: Part 1: The Rim Drives

Most of Canyon de Chelly can only be seen by visitors who are accompanied by an authorized guide, but the Rim Drives are free of charge, no reservation required. Two roads, Indian Route 7, and Indian Route 64 diverge at the entrance to Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Route 7 follows the South Rim of the multi-pronged formation, providing access to seven overlooks, all with killer views into Canyon de Chelly. Route 64 follows the North Rim, and provides access to three more overlooks, with excellent views into the branch known as Canyon del Muerto.

The South Rim drive is a 36 mile round trip, from the Welcome Center to the Spider Rock Overlook and back again, making multiple stops in between. You’ll need a couple of hours to do it justice, depending on how much time you spend at each of the different overlooks. The North Rim drive is shorter, just over 26 miles round trip to the Mummy Cave Overlook. That drive requires another hour and a half, bare minimum, so if you’re going to do both, you should play it safe, and set aside half a day. I can guarantee you’ll consider it time well spent! <<CLICK to Read More!>>

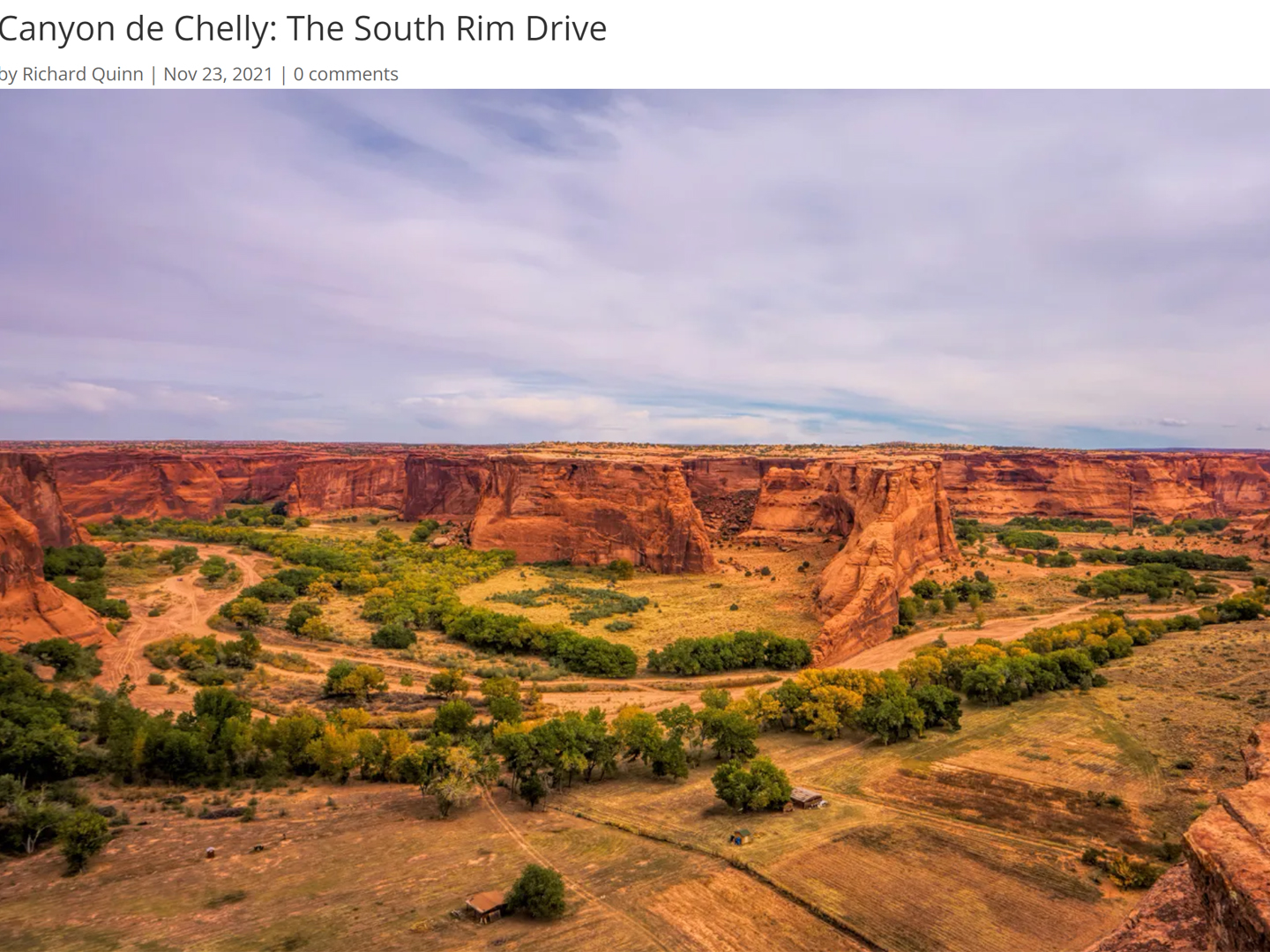

The South Rim Drive

Indian Route 7 begins at the turnoff from US 190, and serves as the main road in the Navajo town of Chinle. If you follow it headed east, it will take you directly to the Visitor Center for the Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Stop there to pick up a map of the park, and to get current information about guided tours and other activities, as well as road conditions, and any closures that might affect your visit.

From the Visitors Center, bear right at the fork to stay on Indian Route 7, the South Rim Drive, and follow the signs to the overlooks.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

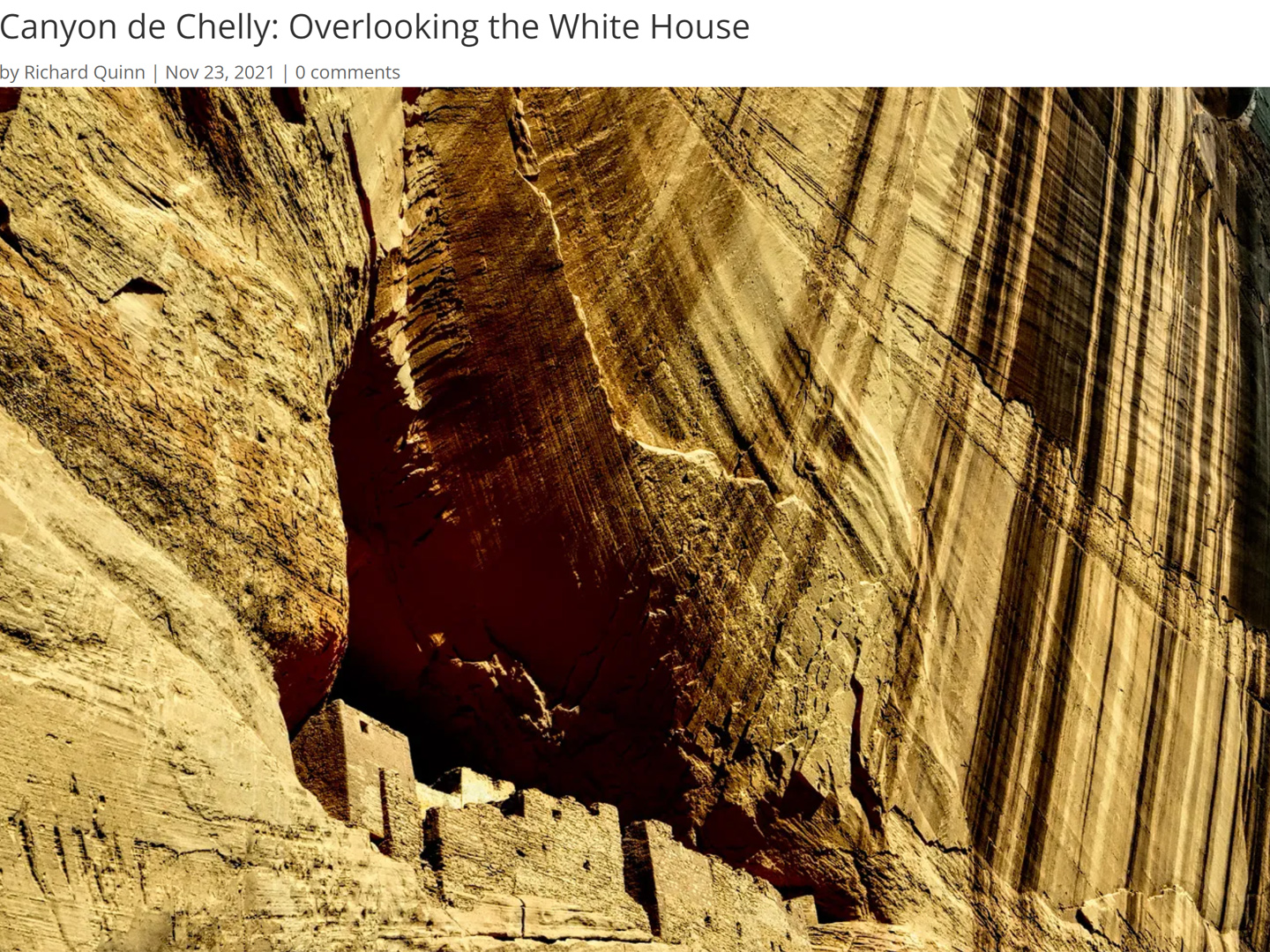

Overlooking the White House

A mile and a half beyond the Junction Overlook you’ll reach the turnoff for the White House Overlook, which is at the end of a half-mile long access road. (Note: the access road, the overlook, and the trail to the White House ruin are currently closed to visitors.) The White House Overlook has always been one of the most popular. The vantage point offers a fabulous panorama of the Canyon, along with an unobstructed view of the White House, one of the best preserved ruins in the National Monument.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The North Rim Drive

Most visitors to Canyon de Chelly National Monument focus the bulk of their attention on the South Rim Drive, but in my view, your trip simply won’t be complete if you don’t take in the North Rim Drive as well.

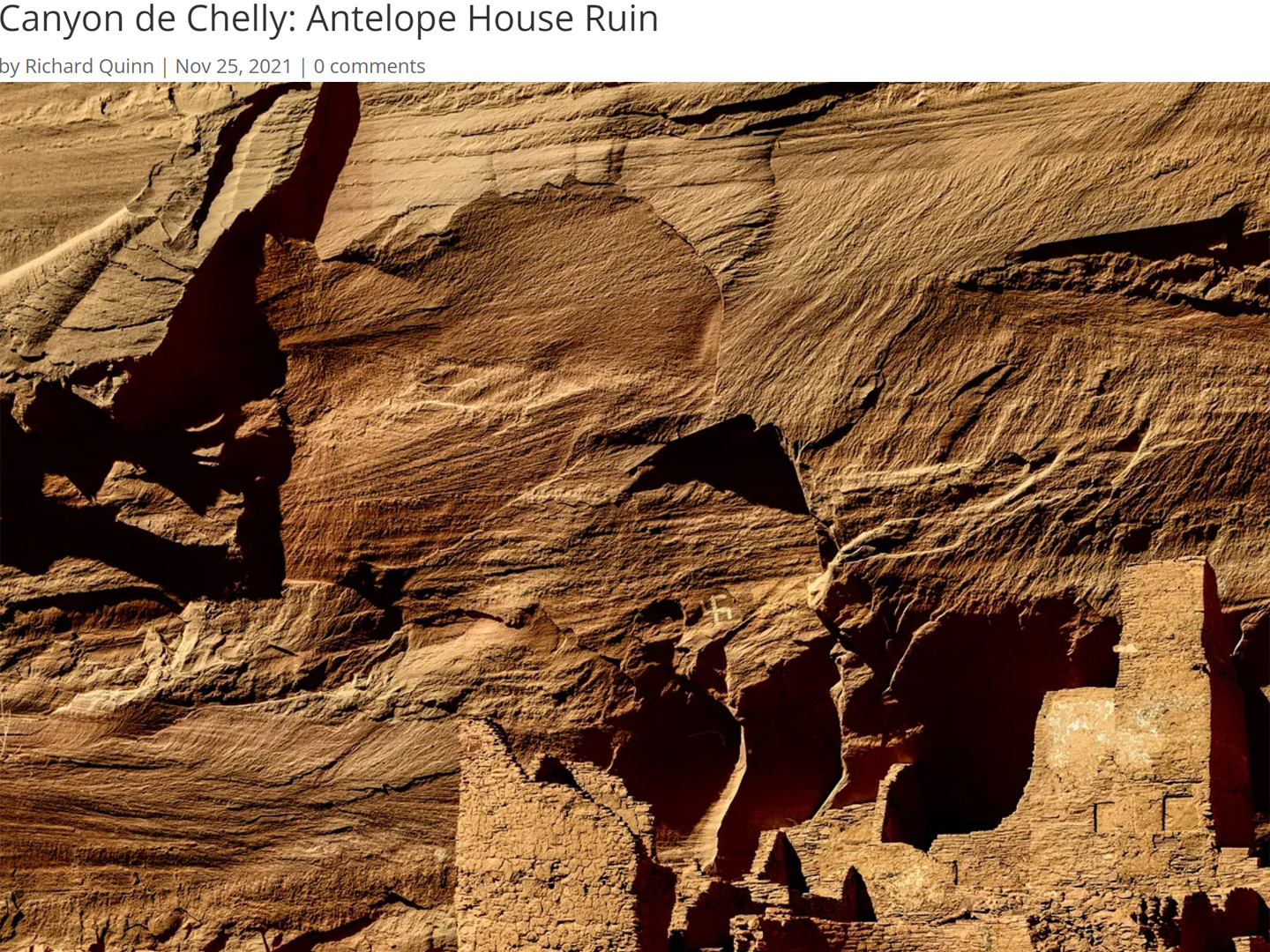

Seven miles from the Welcome Center is the turnoff to the Antelope House Overlook, which is two miles further along a paved access road. The payoff is a fabulous bird’s-eye view of a quite wonderful Anasazi ruin known as the Antelope House. You can still see the crumbling foundations of dozens of rooms, a tower, and at least four circular kivas…

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

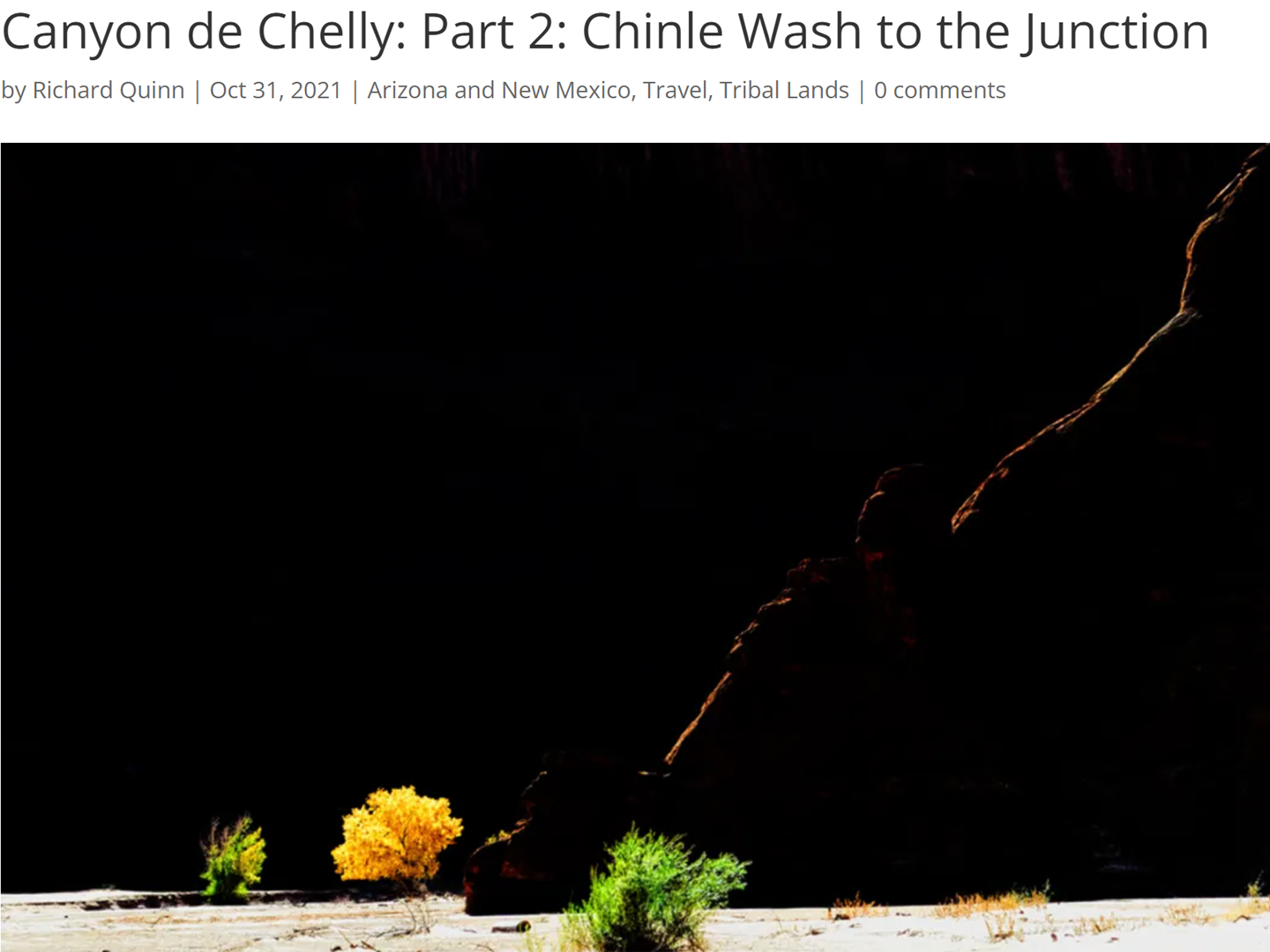

Canyon de Chelly: Part 2: Chinle Wash

Canyon de Chelly National Monument is a place for the whole world to enjoy and admire, just like all of our national parks and monuments, but at Canyon de Chelly there is an essential difference: the rim drives and most of the overlooks offering views into the beautiful canyon are open to the public all year around. The canyon itself, including all hiking trails and Jeep tracks, all the ruins and the rock art, in essence, anything below the canyon rim, all of that is private property, off limits to everyone save the handful of Navajo families who own the land on the canyon floor.

The rest of us can go in, but only to certain areas, and only if we’re accompanied by an authorized guide. A Navajo guide can take you into the canyon in their SUV, or, if you prefer, you can join a guided hike, or a trail ride on horseback. The standard Jeep tours, which are the most popular, range from three to six hours in length. The longer tours cover the highlights of both of the primary gorges, Canyon De Chelly, and Canyon del Muerto.

The series that follows is a detailed account of my own experience in this remarkable place. <<CLICK to Read More!>>

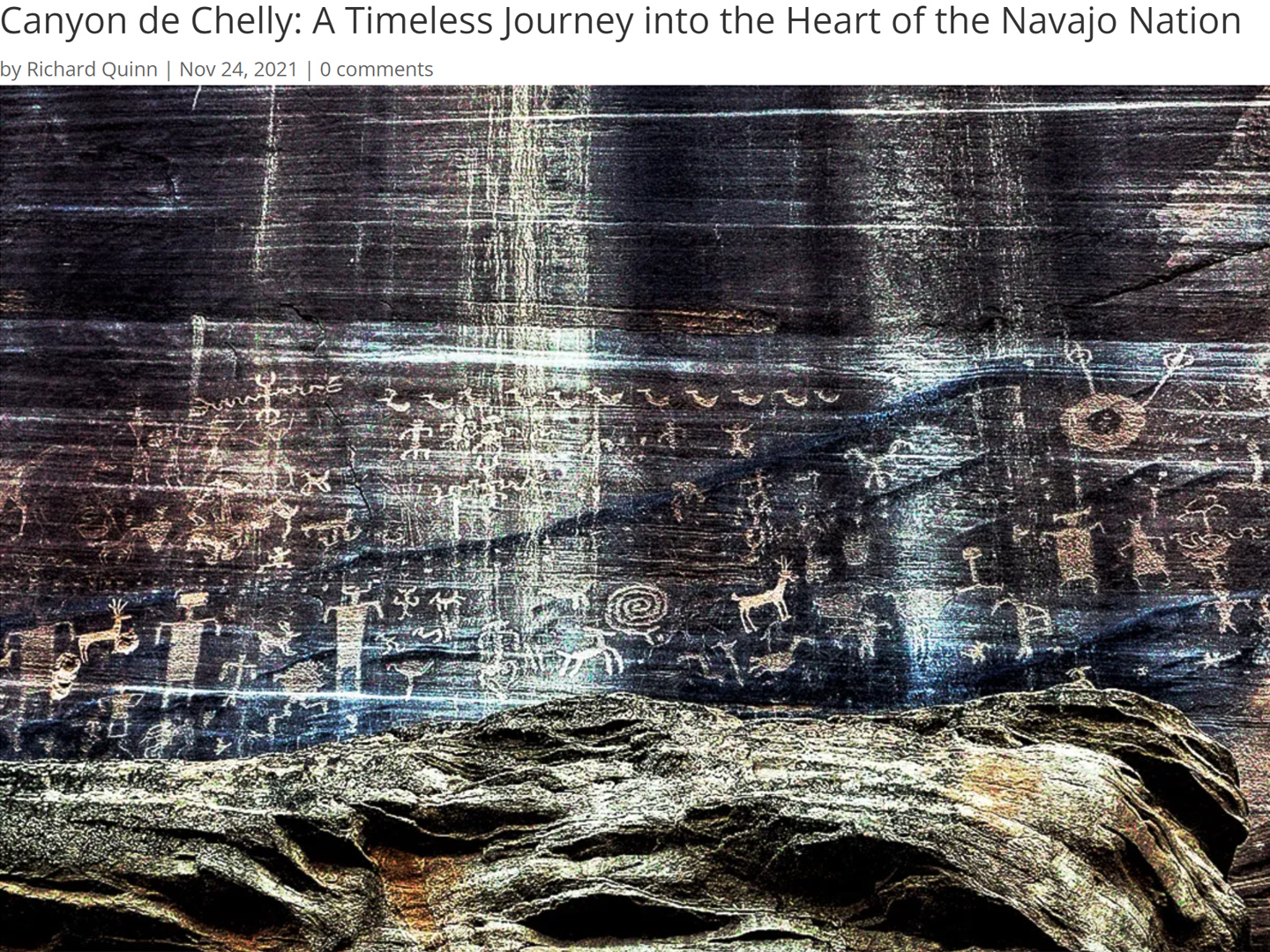

A Timeless Journey into the Heart of the Navajo Nation

At the beginning of our trip, we asked Sylvia to show us her favorite petroglyphs, along with the usual ruins and rock formations, and she did not disappoint. Our first stop, very near the mouth of the canyon was a prehistoric bulletin board she called Newspaper Rock. A smooth segment of cliff face coated with dark desert varnish, featuring an area at least forty feet wide filled hundreds of petroglyphs. The symbols weren’t carved into the rock, and they are not painted. These artists pecked away the dark varnish, creating their pictures by exposing the lighter colored rock underneath: antelope, birds, hunters, and a multitude of intriguing symbols.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

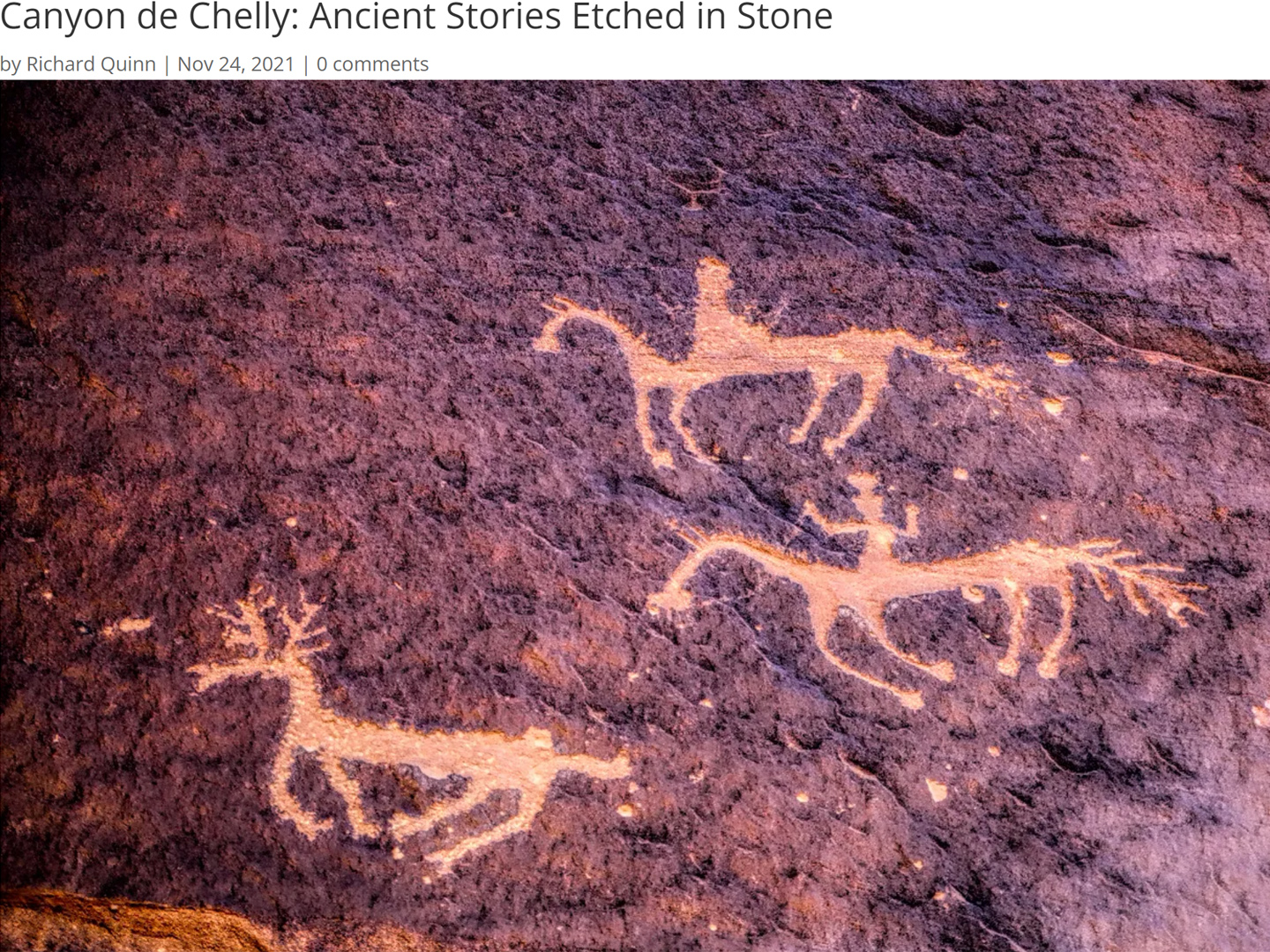

Ancient Stories Etched in Stone

A short distance from Newspaper Rock, just a few steps away along the base of the cliff, we came to another set of petroglyphs featuring riders on horseback. These were most certainly Navajo, and likely date back to the 1800’s. They shared this shady space with other images that were obviously much older. There were hunters, deer, birds, handprints, and more. We crowded in close for a better look.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

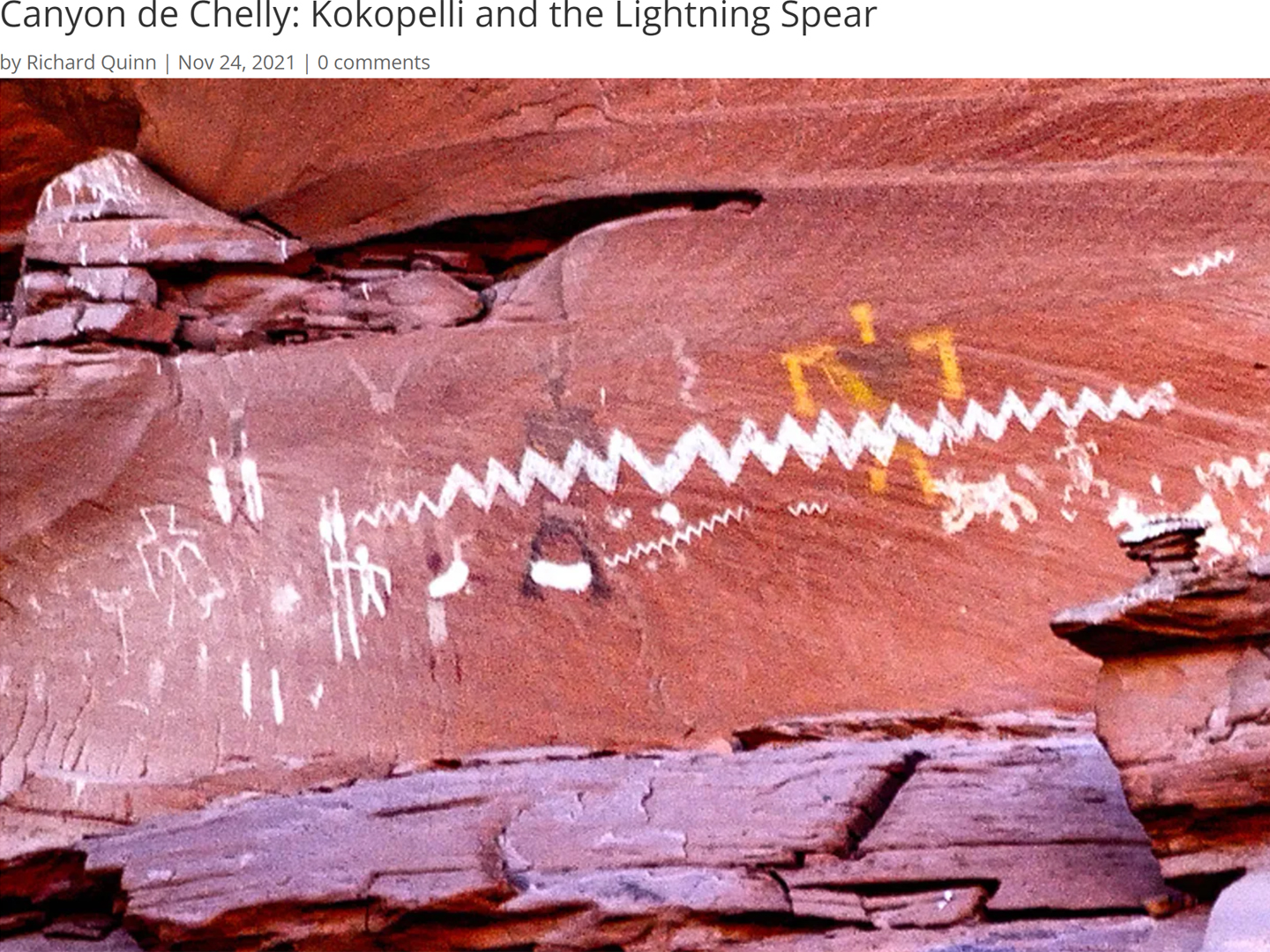

Kokopelli and the Lightning Spear

“When you look at this, there’s a man holding a staff; out of the staff there’s this energy that’s coming out. The figure in black is the patient. The one in yellow is the shaman. The important men of the village are up on the side here, so this was a very sacred ceremony that they were doing. And there are some other drawings on the side; this one here is like a figure of the holy people, because it’s way up there, and it only has the head, and not the arms or the legs. You see a lot of people drawn, and there’s a bird there. And these are drawings of, like, clan systems. The bear, the turtle, and the antelope down here.”

I was probably getting a bit starry-eyed at that point. Barely three miles into the canyon, we’d traveled a thousand years in just under a hundred minutes, and we were barely even underway!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

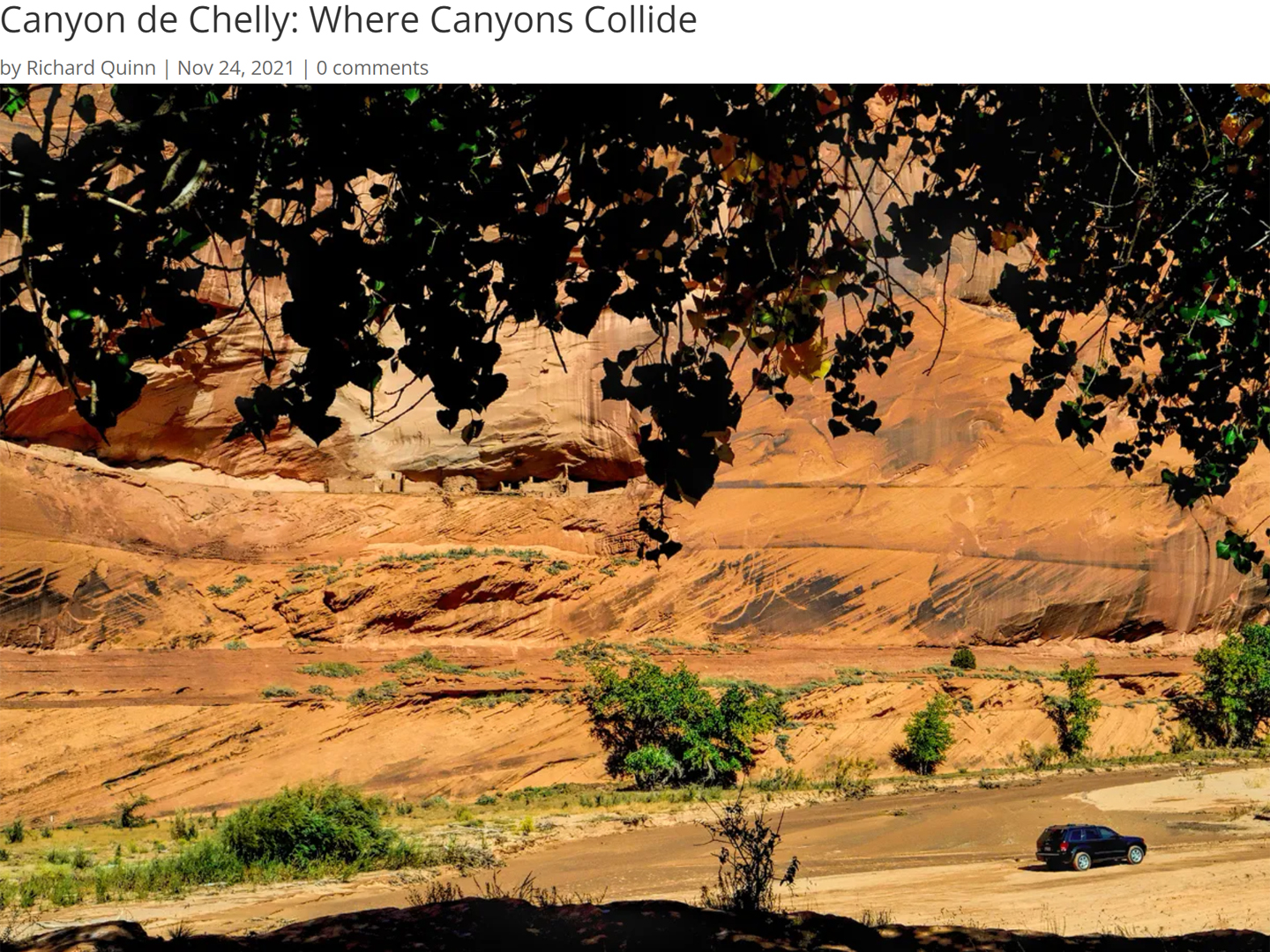

Where Canyons Collide

Just around the bend the canyon opened up into an area wider than any other we’d seen, and right in the middle was a monolithic block of sandstone known as Dog Rock. To the left was the north fork of the canyon, Canyon del Muerto, and to the right, the south fork, Canyon de Chelly itself. The cliffs soared at least 200 feet above our heads, and halfway up the sheer face opposite was another alcove filled with crumbling adobe, a site called Junction Ruin. A bit smaller than First Ruin, and a bit less well preserved, this is an Anasazi structure dating to the same approximate era. The ruin is clearly visible from above at the Junction Overlook on the South Rim Drive; it looks a bit different when viewed from below…

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

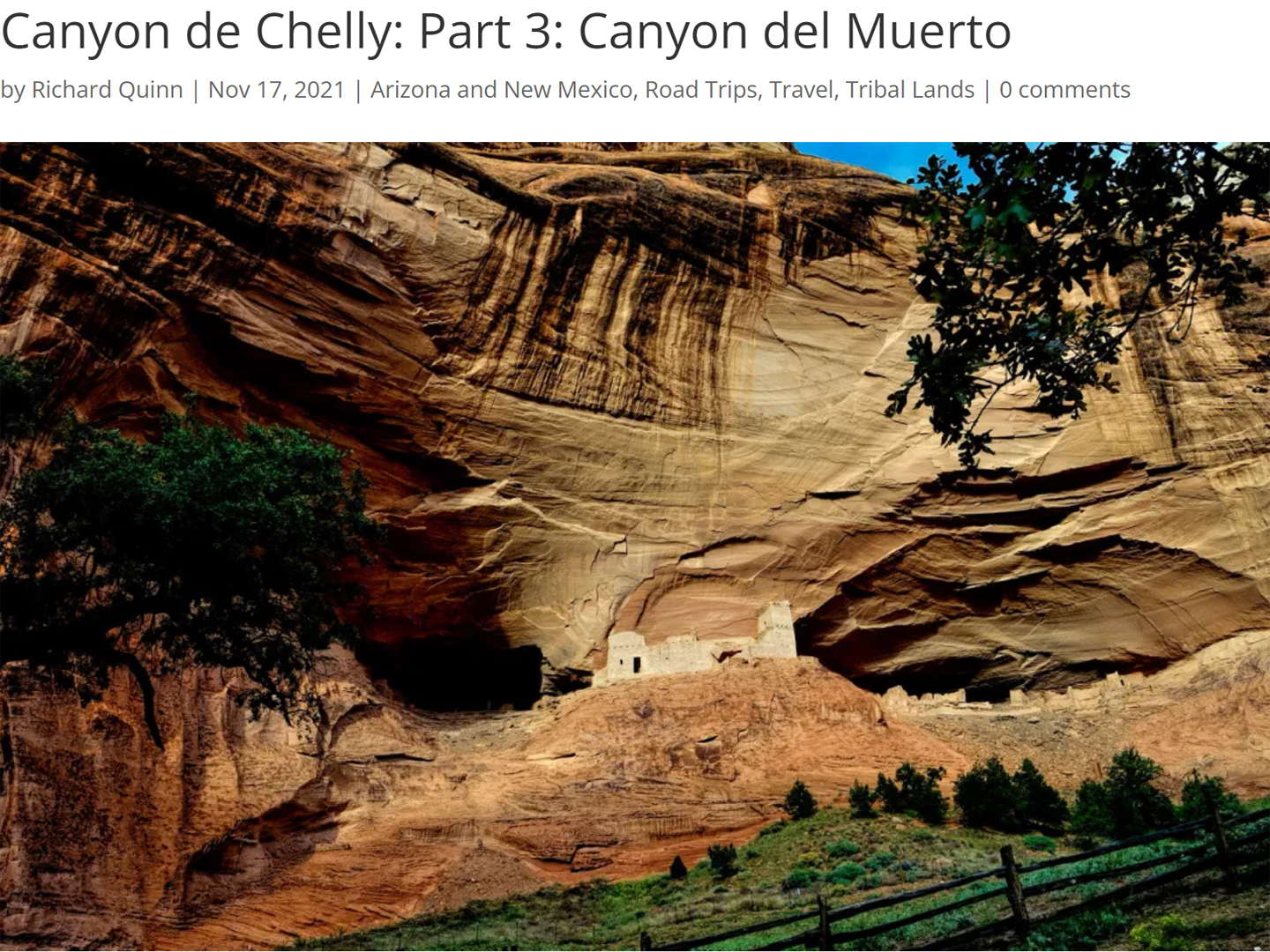

Canyon de Chelly: Part 3: Canyon del Muerto

The left hand fork is the spectacular work of nature known as Canyon del Muerto. The star attraction of this route is the Mummy Cave Ruin, the largest in the area, built on a ledge between a pair of deep caves, high on the face of a cliff in an extraordinary natural amphitheater. It’s a 24 mile round-trip from the Junction, twelve miles of rough road in each direction, with enough twists and turns to qualify as a carnival ride–along with plenty of mud! Along the way you pass the Ledge Ruin, Antelope House Ruin, Navajo Fortress, and Standing Cow Ruin, along with some extraordinary rock art.

The most popular tours last between 3 and 4 hours. Most of them travel into both canyons, but don’t go all the way to the end of either road. Only the longer tours include Spider Rock or Mummy Cave, and only the all day tours include both. Private tours offer the most flexibility, and in most cases, a more comfortable ride.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

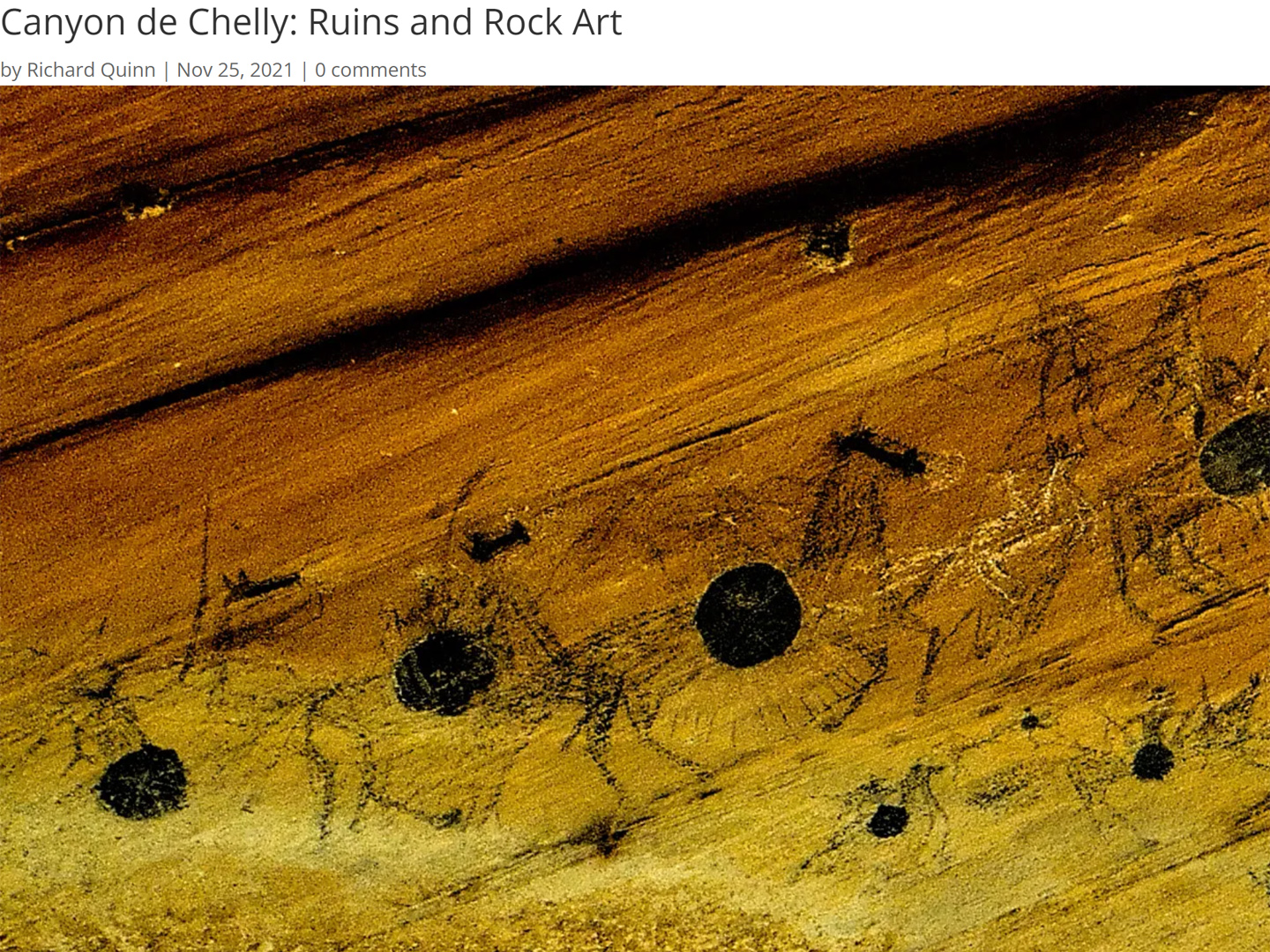

Ruins and Rock Art

In this pictographic sequence, the Utes are on the left, mounted on horseback, with shields and lances, while the Navajos are on the right, on foot, and clearly outnumbered. In one version of the story, just as in Sylvia’s account, the attack took place during a Night Way healing ceremony, in the winter, catching the Navajo by surprise, and at a deadly disadvantage.

The drawings are charcoal, except for the shields, which were painted with pigment made from the bee weed plant. The sandstone overhang provides some protection, but after 150 years or more, the panel is weathering, starting to fade and flake away. Many of the rock art panels in these canyons are in danger of irreversible deterioration from exposure to the elements. Pictographs such as these, done with charcoal and other natural pigments, are particularly vulnerable to the ravages of time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Antelope House

Antelope House was formally excavated in the early 1970’s, by archaeologists working with the National Park Service. Each new culture that occupied this site built atop the remains of their predecessors, so as researchers dug into the stratified foundations, they found the pit houses of the Basket Makers at the bottom, and layers of increasingly sophisticated cultural remains, from the Ancestral Pueblo to the Pueblo people, the Hopi, and the Navajo, each of these groups contributing to the timeline of an area that is exceptionally rich in history.

Of all the ruins and other archaeological sites in Canyon de Chelly, Antelope House is the most thoroughly investigated. That’s at least partially due to simple ease of access: unlike most of the ruins in the canyon, all the primary structures at this site are at ground level.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

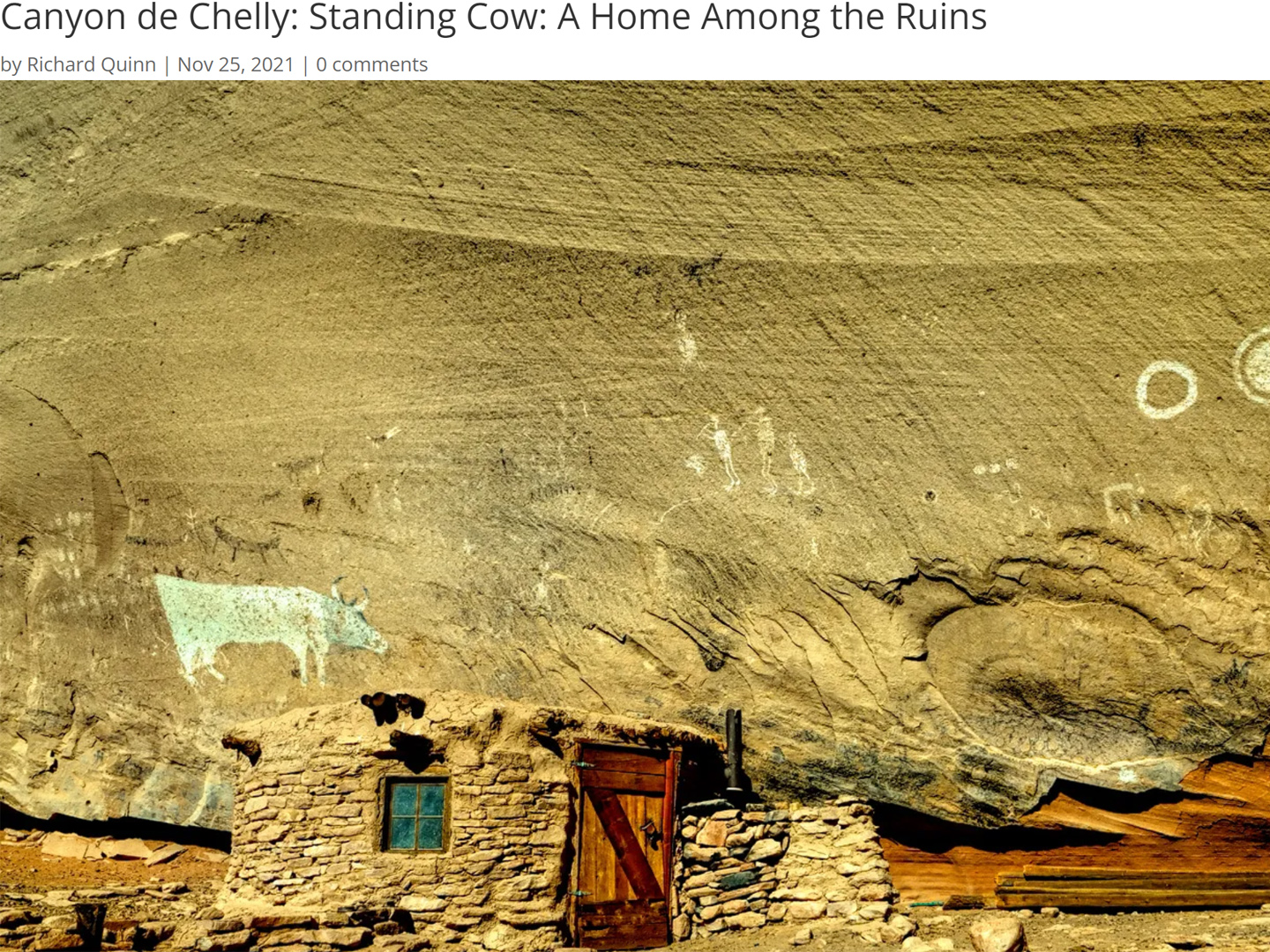

Standing Cow: A Home Among the Ruins

The hogan, much newer than the other structures, was built using sandstone bricks recycled from the surrounding ruins. That would never have been allowed today, but at the time, before the National Monument was established, there weren’t any rules against it, so Sylvia’s great grandfather was simply being practical, using what was available. Today, Standing Cow is on all the maps, as much a part of the human landscape of Canyon de Chelly as the White House and the Mummy Cave. We felt quite privileged to be there with someone who was so directly connected to all of it.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

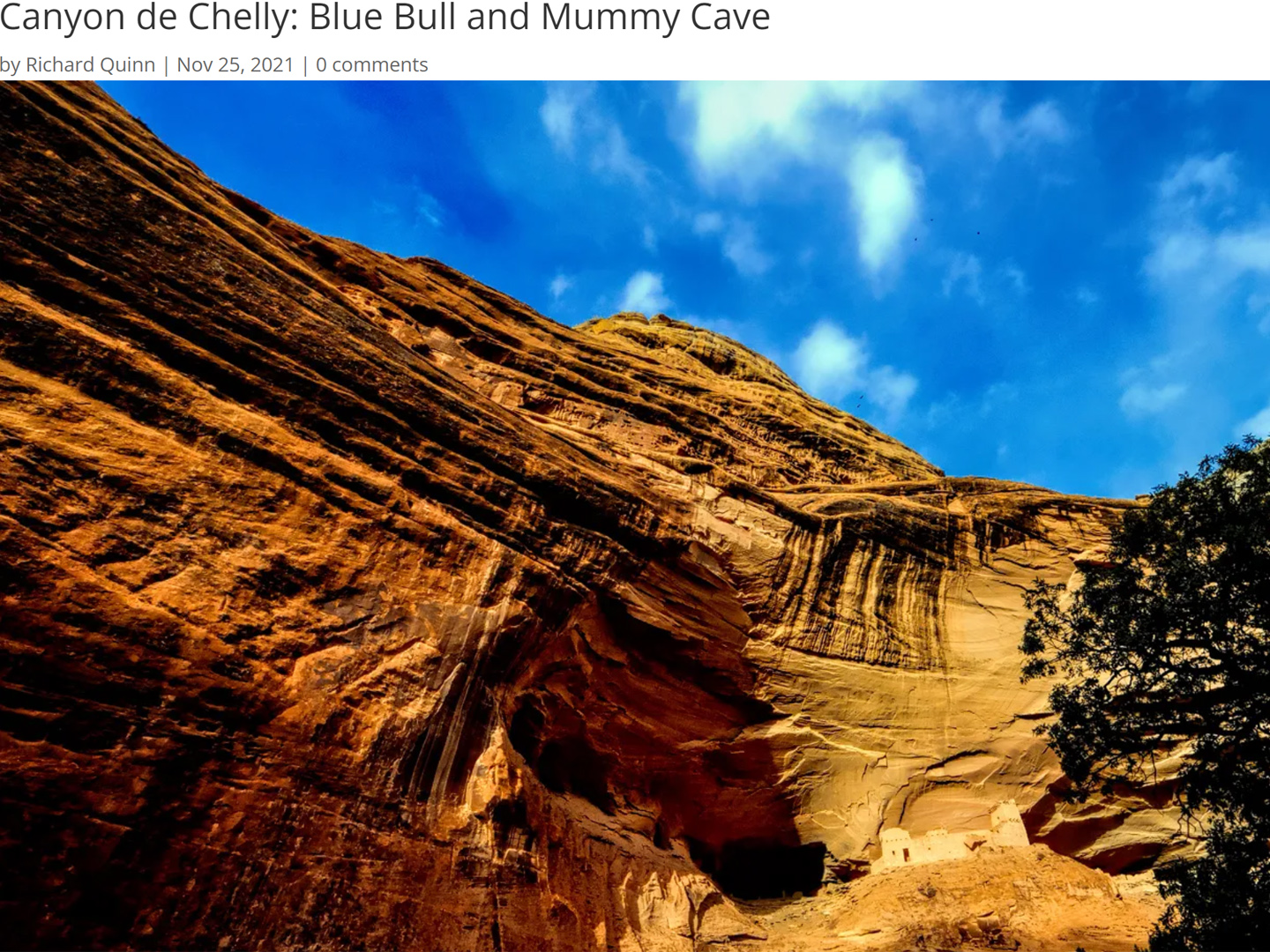

Blue Bull and Mummy Cave

300 feet above the canyon floor, there are two deep alcoves filled with ruins, and on a wide ledge between them, a large, multi-story pueblo, partially reconstructed, and quite impressive. The setting is a natural amphitheater, and the overall aspect of the place is simply stunning.

Occupied for a thousand years, from around 300 A.D. until 1300 A.D. The whole complex, including the main building and the structures in the two flanking alcoves had as many as 70 rooms, including living quarters, ceremonial spaces, and storage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

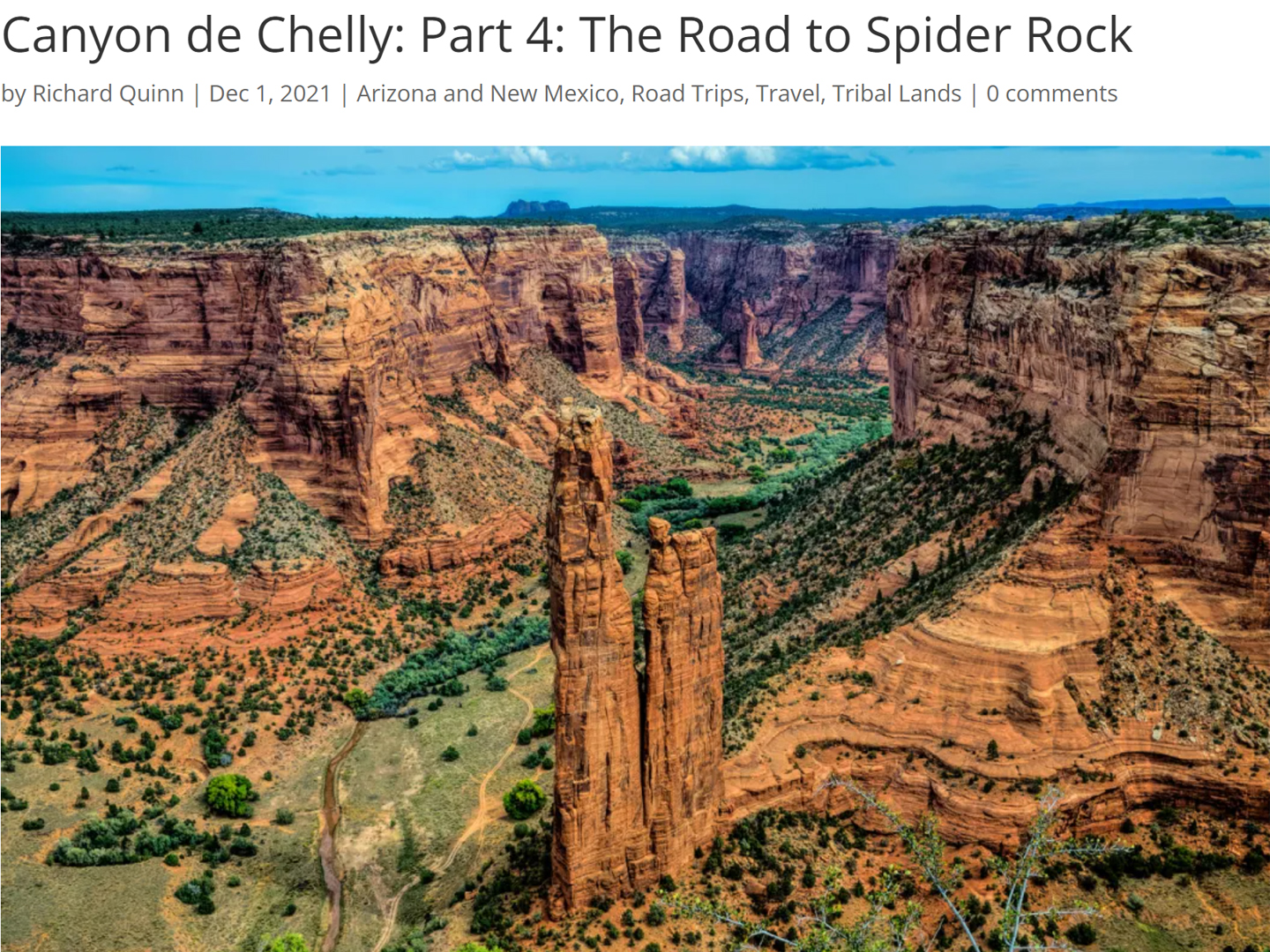

Canyon de Chelly: Part 4: The Road to Spider Rock

Today, only authorized Navajo owned vehicles are allowed inside Canyon de Chelly, but this was in 2013, when it was still possible to drive yourself in your own 4×4, as long as your Navajo guide rode along with you. That arrangement was Sylvia’s specialty, and driving through that canyon, with her ongoing expert narrative providing background on all the points of interest, was some of the best fun I’ve ever had.

The first part of the route was aleady familiar to me. We entered Chinle Wash from that same dirt road, just past the Visitor’s Center, and I took off down the sandy creek bed, keeping up a steady speed and zig-zagging diagonally across the deepest ruts, to avoid getting trapped.

We passed by all the places where we’d stopped the day before, and made it all the way to the junction in just over half an hour. This time, we took the right hand fork, and we hadn’t gone far when we ran into our first big challenge of the day: a steep downslope that crossed a wash, with deep mud at the bottom of the hill.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

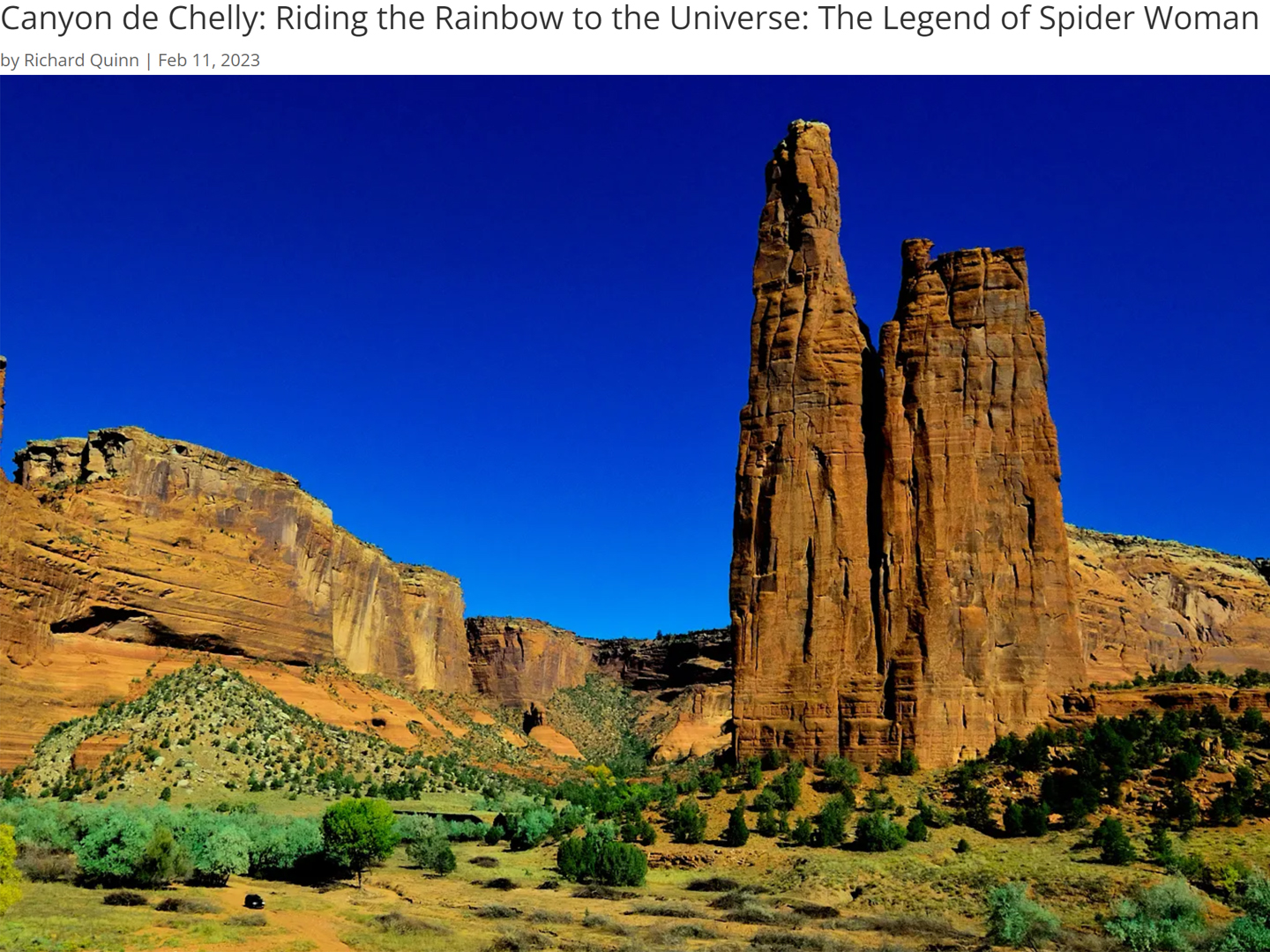

Riding the Rainbow to the Universe

Viewing Spider Rock from below provides a dramatically different perspective on this extraordinary formation. From above, you’re looking down on the whole tableau, and Spider Rock, shorter than the soaring canyon walls, appears as one small part of the larger scene. From below, from the floor of the canyon looking up at it, you can see just how BIG the danged thing is. At 800 feet in height, it’s a good bit taller than your average 50 story sky scraper, and it completely dominates the landscape.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

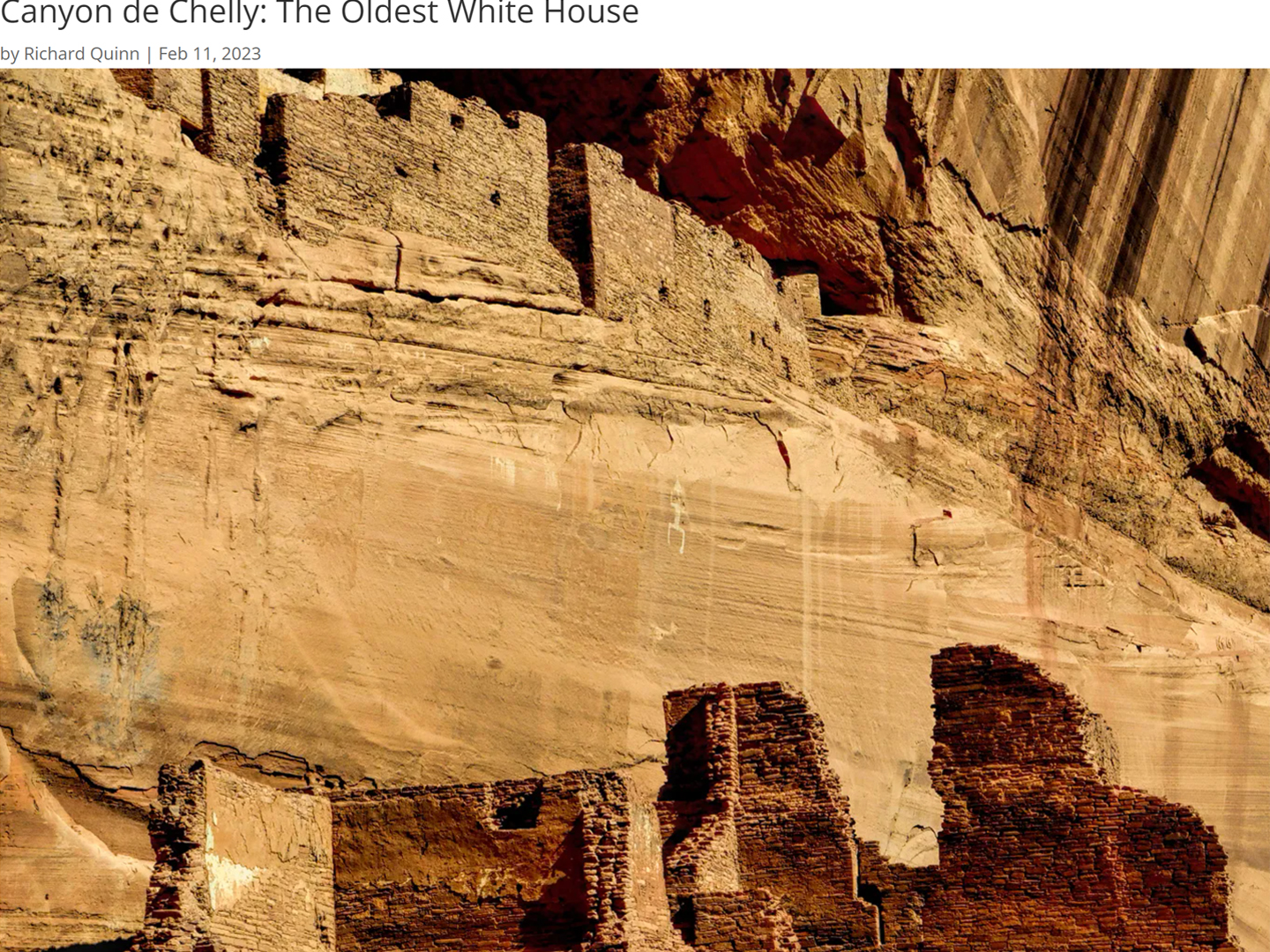

The Oldest White House

At the center of the upper section is a large room, 12 by 20 feet, with a front wall that is 12 feet high and made of stone that is two feet thick. This wall was coated in white plaster, decorated with a yellow band, and it is this white wall, which can still be seen, that inspired the name La Casa Blanca, the White House, to this ancient dwelling that has endured in this place for nearly a thousand years.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

0 Comments