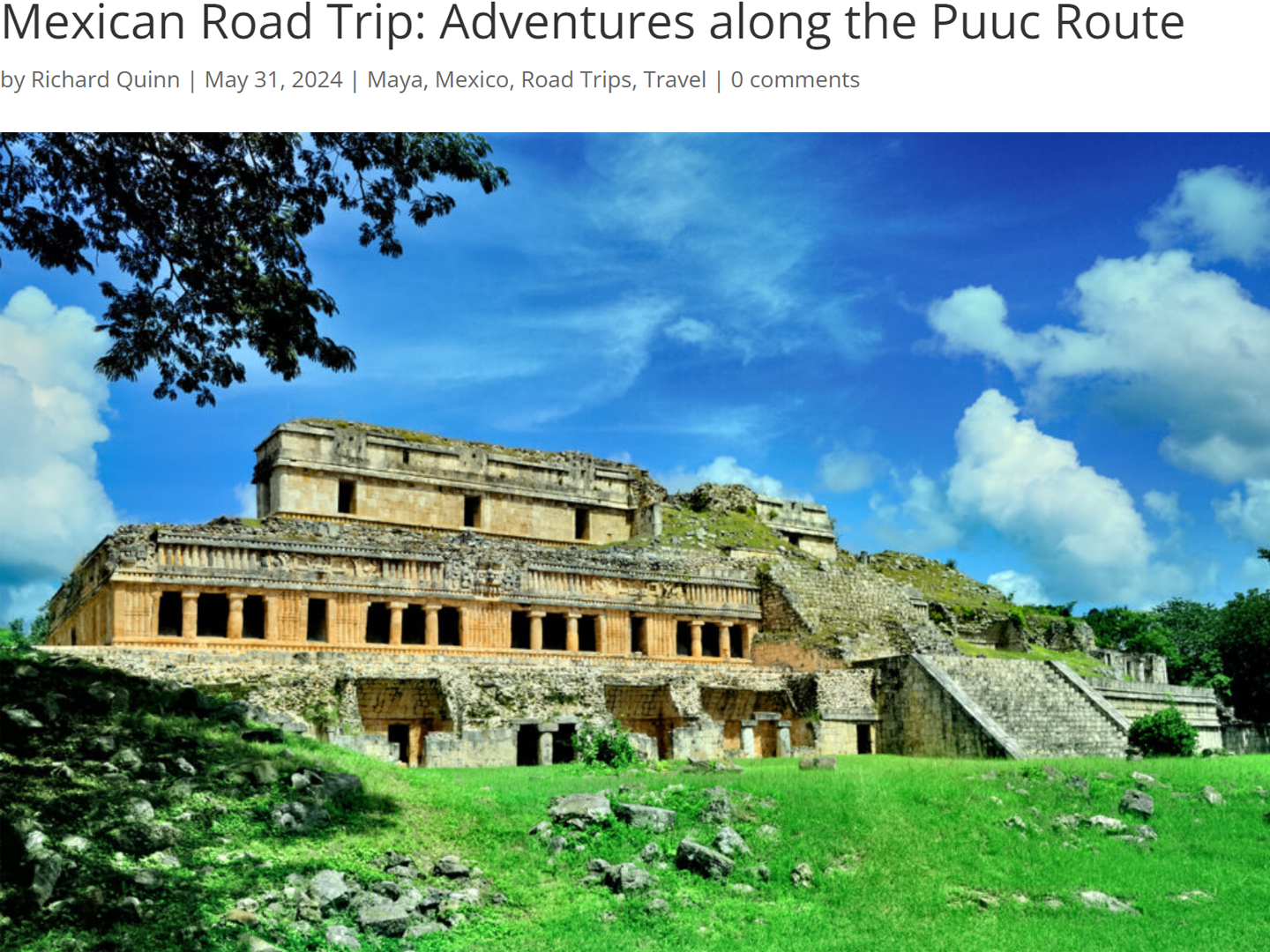

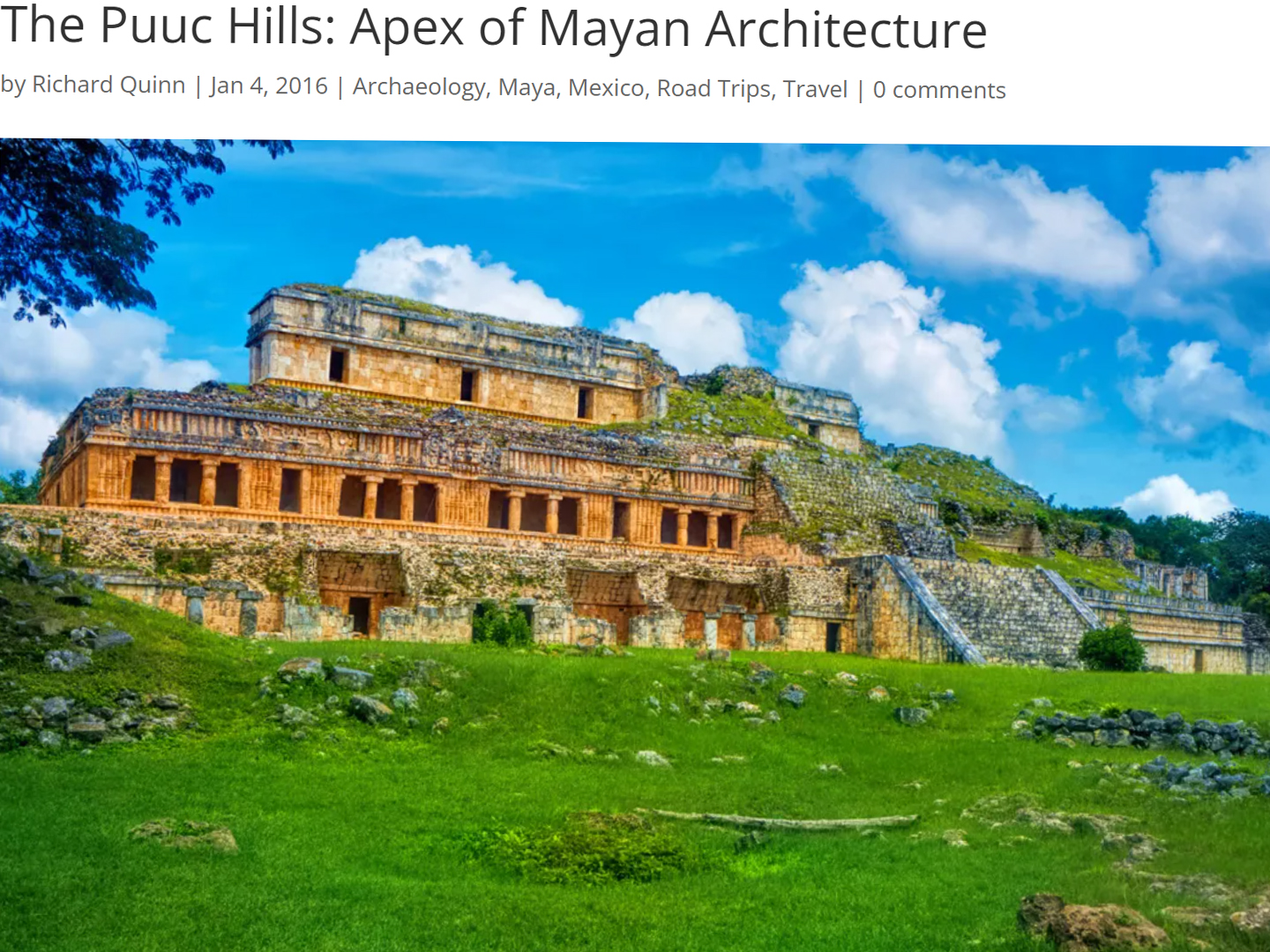

Most of the Yucatan Peninsula is relentlessly flat, devoid of any geological feature much taller than a tree, but there is an area just inland from Campeche and Merida where the karstic limestone bedrock folds on itself, creating a jumbled range of low mountains known as the Puuc Hills. This region was quite densely populated in the late classic period, roughly from 700 to 1000 AD, a period that saw a stunning florescence in Mayan art and architecture, including the emergence of what’s come to be known as the Puuc style, which was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship of the ornate facades that characterize this architectural style was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

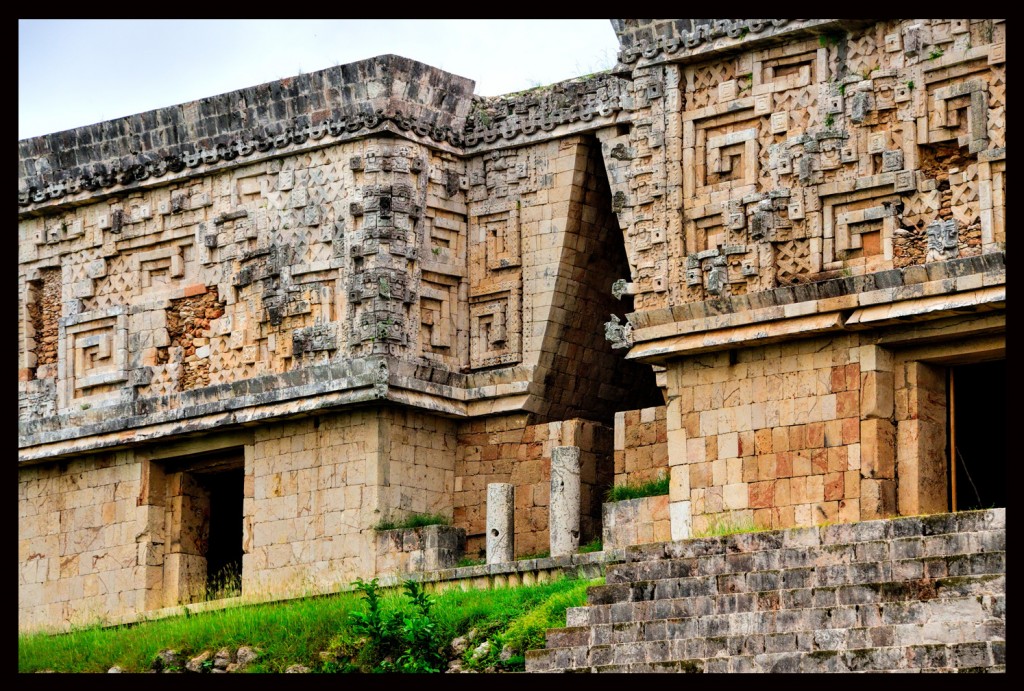

The Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, widely considered the finest, best preserved example of Puuc architecture. (Click any of these photos for an expanded view).

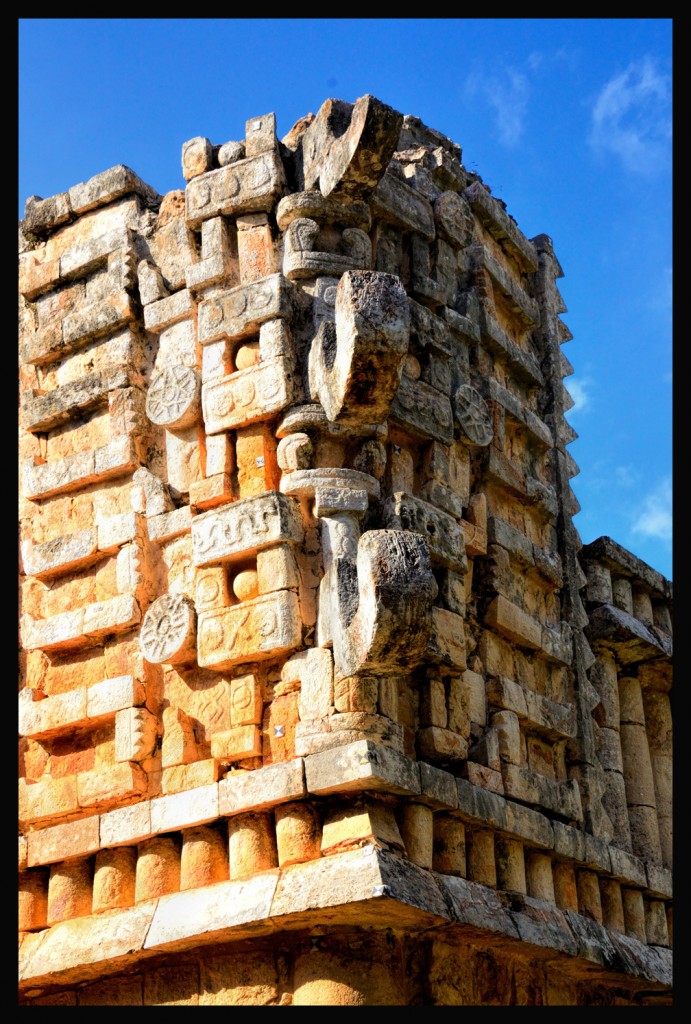

Earlier buildings were constructed of walls built from heavy stones piled atop one another like bricks, and bonded with cement made from pulverized limestone. The big innovation of the Puuc style was the use of built-up concrete as a structural core for the buildings, instead of the thick stone walls, allowing for more spacious interiors. Thin-cut veneer stones were set into the outside surface of the concrete core, as a facing for the buildings. The lower sections of the facade were smooth rectangular blocks, while the upper sections were elaborate designs, geometric patterns that incorporated representations of Mayan deities, most notably Chac, the big-nosed rain god.

Three carved stone images of Chac, the rain god, one atop the other.

Another prominent feature of the Puuc style is the corbeled arch:

The Maya never quite figured out the concept of a keystone, so these were not true load-bearing arches. Even so, they were quite solidly constructed.

It’s not uncommon to see one of these Mayan arches standing alone, long after the rest of the wall or building it was a part of has crumbled to the ground.

Cut stones that comprise the decorative friezes surrounding the tops of these buildings were mass-produced in advance and assembled like pieces of a puzzle, allowing uniformity unlike anything that came before.

Some assembly required. Cut stone litters the ground near the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal.

The friezes that form the upper sections of these facades are extraordinary in their complexity and their near perfect symmetry.

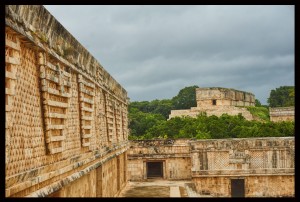

Relative location of Maya sites along the Puuc Route

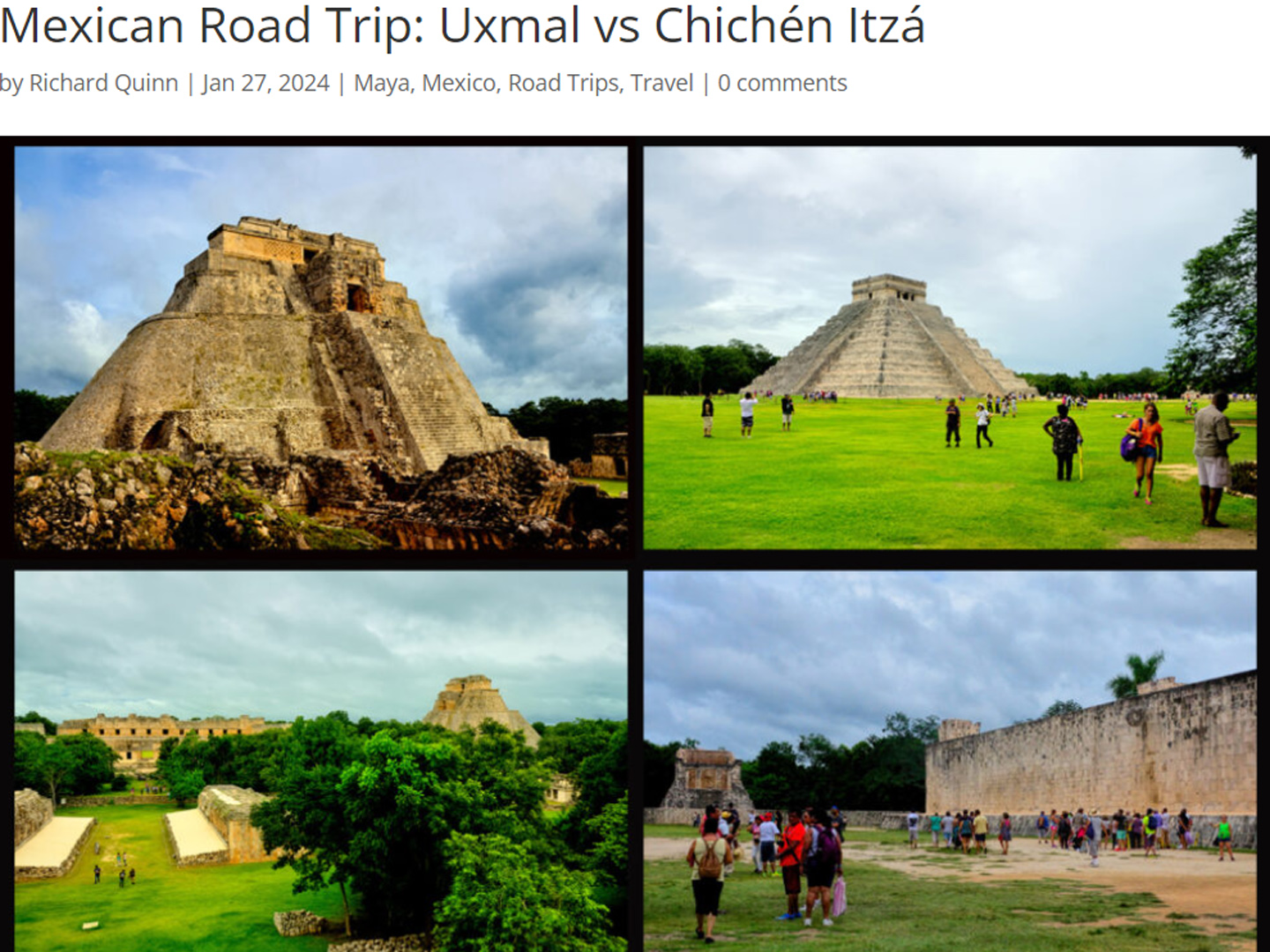

Uxmal is considered the pinnacle of Puuc architecture, but that site was well-covered in a previous post to this blog (Uxmal). This article will focus instead on several of the lesser known sites along the Puuc Route, beginning with:

Tacob:

This was a true rarity–a Mayan site right on the highway that was so obscure it wasn’t even on our map. We spotted a small sign alongside the road:

So we pulled over:

It was open? Though I’m not quite sure how they could have closed it. The gate, and the fence, was more decorative than deterrent.

What they did have was a caretaker. The site didn’t get many visitors, so he was happy to see us, and quite enthusiastic

The site had actually been discovered years before, and was alternatively known as Tohcok. It was one of the dozens, if not hundreds of smaller Mayan ruins waiting their turn to be excavated and studied. The two largest structures at Tacob/Tohcok had been buried under mounds of earth for centuries, until no more than ten years earlier, when researchers finally got around to digging them out. There were as many as forty other structures in the area that were buried still.

The architecture is of the Puuc style (naturally), with elements of the Chenes style:

As exemplified by the Chac mask on the lower corner of this building.

A particularly interesting element was this stylized flower of a corn plant. The head of a warrior, sideways within the corn flower, symbolizes the rebirth that follows sacrifice, or death in battle.

Research and restoration at this site is an ongoing, long-term project. It’s not a major, glamorous ruin, so funding for continued work here is barely a trickle. The caretaker does it all, even to the extent of making his own signs:

Leaving Tacob, we continued north on Route 261 for about 60 km, until we reached a sign pointing us to the turnoff for three Puuc Route sites that are literally side-by-side, starting with:

Sayil:

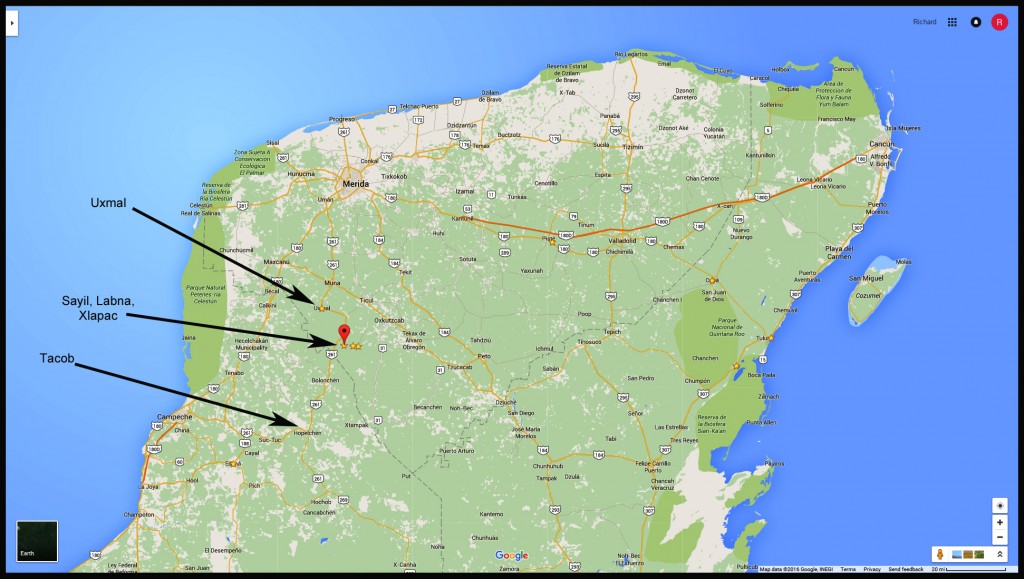

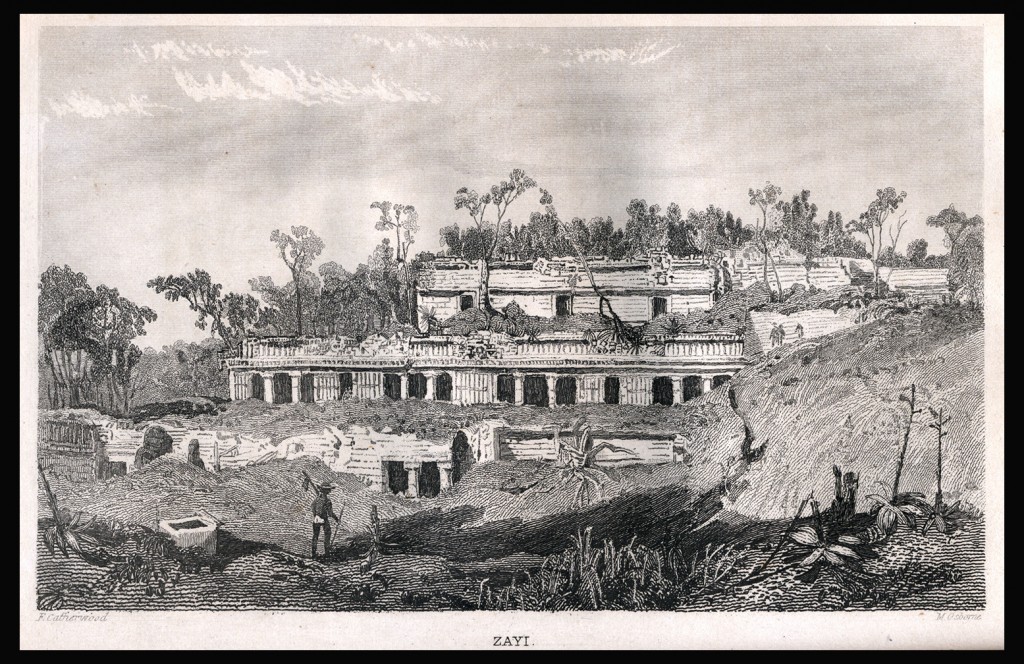

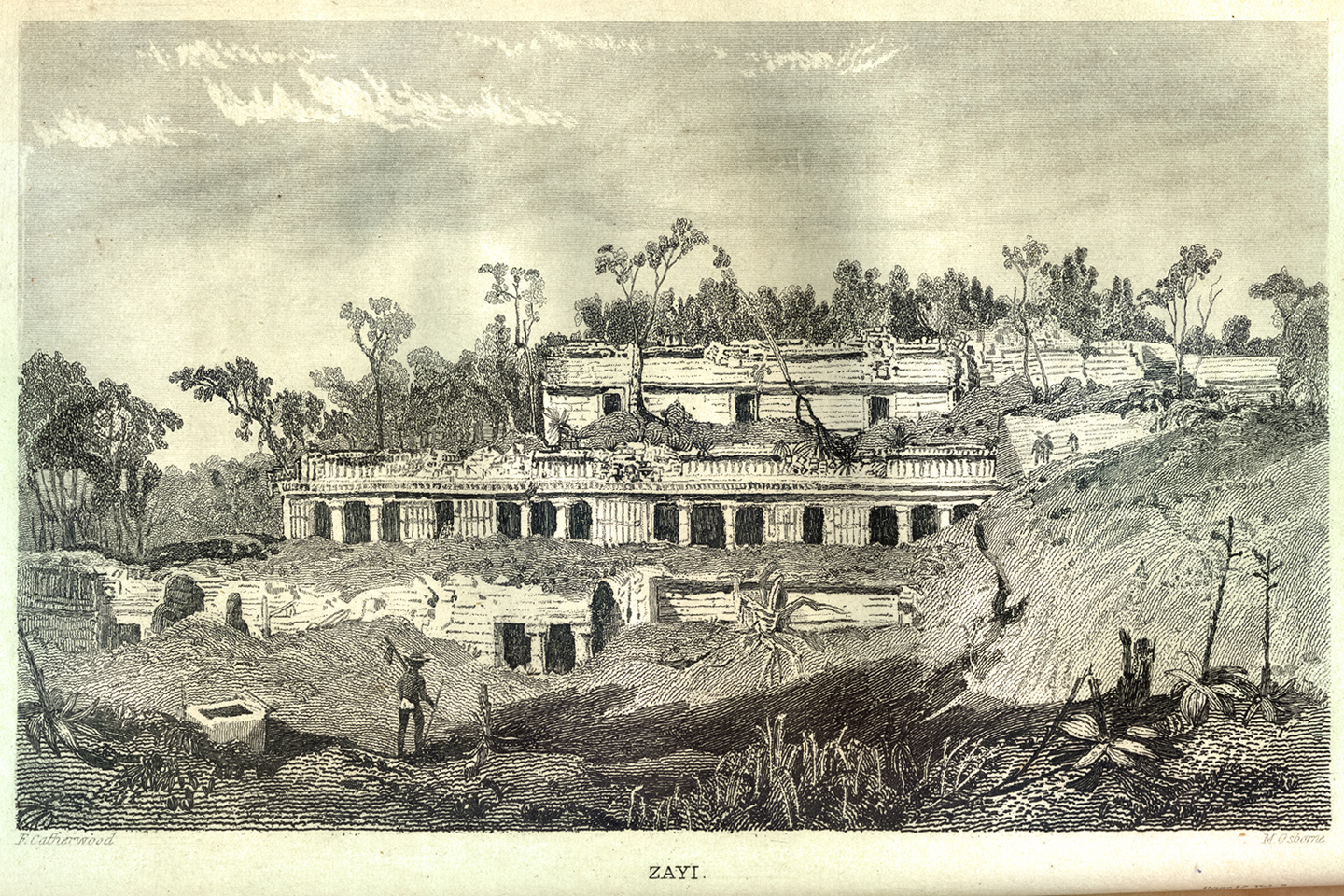

This was a true gem of a Mayan ruin. Images of the grand palace at Sayil are well known, ranking right up there with the Castillo at Chichen Itza and the Palace at Palenque as being the ultimate examples of the beauty, and the grandeur of ancient Mayan architecture. The site was first brought to the attention of the outside world when the grand palace was sketched by Frederick Catherwood, who famously visited this ruin with John Lloyd Stephens in 1841. Catherwood’s sketches were published in Stephens’ book, Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, originally published in 1843. This book, with its phenomenally precise illustrations, was the original sensation that introduced the Maya and their mysterious abandoned cities to the rest of the world, and the grand palace of “Zayi”, as they called it, was one of those images that most captivated the attention of the book’s many readers. That said, despite being the home of such a famous monument, Sayil, the archaeological site is hardly known at all, and when we visited, we had this phenomenally amazing place entirely to ourselves.

The Grand Palace at Sayil, from a drawing done by famous illustrator Frederick Catherwood in 1841. The image below is a black and white photograph of the same structure, taken in 2015 (almost 175 years later).

Sayil was a regular Roman Candle, as Mayan cities go, shooting into prominence like a rocket, burning brightly, if briefly, then just as quickly fading away. Unlike most of the sites that I visited personally, there was no millennium (or more) of continuous history here. Sayil wasn’t even founded until well into the Late Classic period, around 800 AD, and it reached it’s peak a scant 100 years later, with a population of close to 10,000 souls in a city that spread out for about five square kilometers. Fifty years after that, by 950 AD, the place went into a rapid decline, and was abandoned by 1000 AD, in concert with most of the other Mayan cities in the Yucatan. Drought was the likely culprit, as these centers were dependent on rainwater stored in elaborate cisterns. With an extended drought, there wouldn’t have been enough water to sustain agriculture at the level needed to feed all those people.

A carving of the Diving God, part of the elaborate frieze surrounding the Grand Palace. The Diving God is thought to represent Ah Muzencab, the Mayan Bee God. Honey had great value in this society, and was, like other luxury goods, an important medium of trade.

El Mirador, the Watchtower, which is really little more than the remains of a roof comb atop a small, crumbling temple. The pyramid that this temple once crowned has completely collapsed.

A Mayan god of fertility? Or so says the sign. This is far from the only representation of sex in Mayan art and architecture, and it’s certainly not the most graphic, but, at a good six feet in height–it’s probably the biggest!

Our next stop along the route was supposed to be Xlapac, but we somehow missed the turn, and, just a few kilometers down the road, we came to:

Labna:

Another late classic site from essentially the same era. The first thing you see walking in is the small palace complex:

There are Puuc style buildings, with elaborate friezes decorating the upper sections of the walls. Leading away from the palace complex was a raised causeway:

The causeway, or sacbe, which leads to a plaza dominated by this thing:

Another Mirador, or Watchtower, much like the one at Sayil. Here at Labna the supporting pyramid–actually nothing more than a big pile of rocks–was still more or less intact. The pyramid most certainly looked a good bit more finished when it was first built. The exterior layer of stones would have been cemented into place, possibly even stuccoed, but all of that has long since worn away. The roof comb, which is also pretty much intact, is a common element on Mayan temples, especially those that crown the tops of pyramids. There are protruding stones that give it a studded appearance:

The studs, or tenons, were there to support plaster figurines and bas reliefs, all of which would have been integrated into an elaborate design, and painted. That’s not just conjecture: at many of the Mayan sites, numerous traces of the mineral based paint used on the exterior of buildings has survived. It’s never completely there, of course–not after a thousand years, but there are still patches and swatches, on sections of walls that have been protected, at least to some extent, from the ravages of time, wind, and weather. The predominant color, and seeming favorite? That would be red. Blood red.

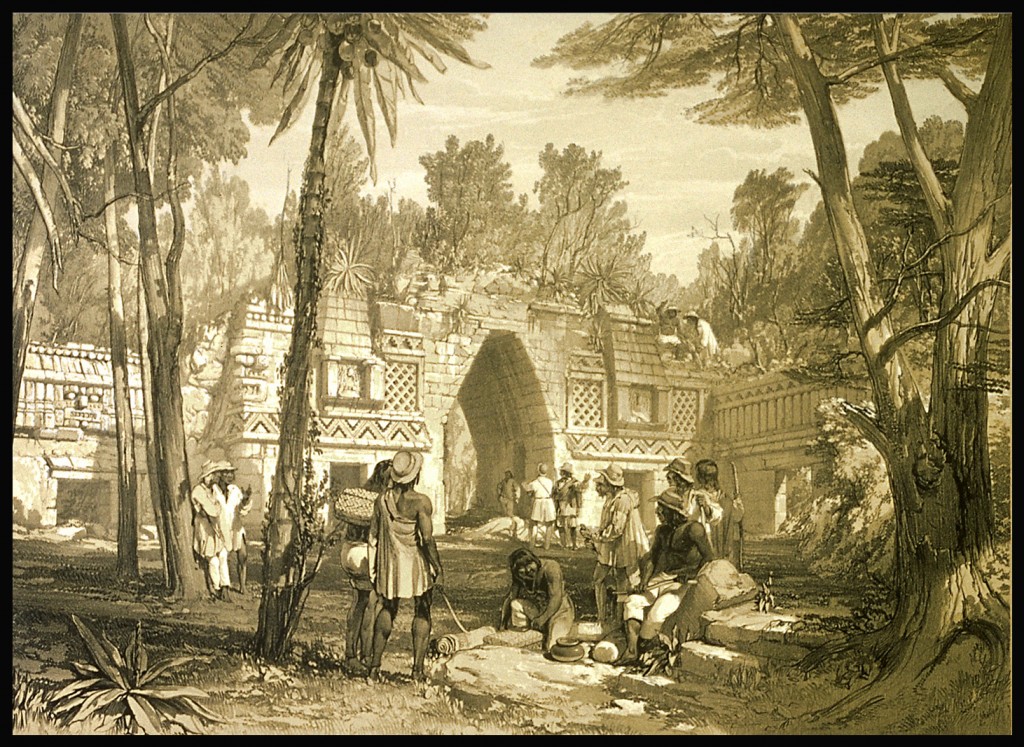

Alongside the Mirador was another complex of structures that included this arch, which was thought to have been a passageway between sections of the ceremonial complex at the core of the city. The sepia tone print was from a quite famous lithograph based on an original on-site line drawing done by Frederick Catherwood, who visited Labna in 1841 with travel writer John Lloyd Stephens. The book recounting their adventures, Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, was published in 1843, and was an instant sensation, particularly in England, bringing to center stage the mysterious Maya and their lost cities in the jungles of Central America.

Labna was not large. It was quite similar in size to Sayil, and both of them were subordinate, economically, as well as militarily, to Kabah, a somewhat larger center nearby that was, in turn, subordinate to Uxmal. When it comes to Mayan cities, bigger is always badder, hence, more powerful, although it must be said that the lack of fortifications in the cities of the Puuc Hills indicates relatively peaceful coexistence. Monumental construction was hugely expensive. The larger the monuments, the greater the expense, and it wasn’t a bill that could be paid strictly with gold, or its equivalent. The cost of a pyramid was measured in human lives. Many given, many taken, many more simply–used up.

Labna arose about the same time as Sayil, it’s palace dating to around 850 AD. It reached it’s peak at the same time, around 900 AD, and it fizzled and died at around the same time, abandoned by 1000 AD, in concert with all the others.

Leaving Labna, we had a decision to make. It was after 4:00 PM, too late in the day to go on to Kabah, but Xlapac had to be really close. Our map showed it smack in between Sayil and Labna, which were less than five minutes apart by road. We hadn’t seen any signs on the way east, so we turned back to the west, and this time we found the side road and the entrance to:

Xlapac:

This was the smallest of the bunch, so small they didn’t even charge any admission! But even though it was free to get in, they still closed at 5:00 PM, so we didn’t have much time. And with what time we did have, I’m embarrassed to admit that we blew it! There are only three buildings of any significance at Xlapac, and only one of those is of any REAL significance: the Palace. With our limited time we only managed to fit in two of the three buildings–and guess which one we missed? I’ll blame myself for that wrong turn–and it gives me a reason to go back. What little we did catch wasn’t exactly stunning when compared to everything else we’d seen, but it still had its charms. Of a piece with Sayil and Labna (predictably enough). Heavy on the Puuc architecture, and lots of images of Chaac, the rain god.

One of the Puuc style buildings in Xlapac

Some details from said building. Heavily featured: big-nosed Chaac, everybody’s favorite rain god.

Sadly, that’s about all we got out of Xlapac, which was really an extension of the other sites. More like a different neighborhood than a different city. All of the Puuc Hills sites were connected by much more than just the sacbes, by more than a common style of architecture. These were one people who lived together in this unique territory. Lived together, and, ultimately, died together.

The Puuc Route is easily accessible from either Merida or Campeche. I’d be reluctant to recommend trying to visit all of these in a single day, including Uxmal, but I suppose it really depends on how much time you have. They’re all quite close together (except for Tacob, which is near Hopelchen, close to Campeche). So it’s theoretically possible–you’d just need to pace yourself, and you’d likely be a bit rushed. Best bet: devote one whole day to Uxmal, and do the others on Day 2. These would be a difficult day trip from Cancun–it’s a bit too far, so plan on staying in Merida or Campeche, or at one of the lovely hotels near Uxmal. There are tours, of course, out of both Merida and Campeche, but for the Puuc Route? I would strongly recommend renting a car. That way, you can set your own pace, and, with the exception of Uxmal, these sites are small enough that a guide won’t really be necessary. If you do rent a car, and you drive it on Mexico Route 261, I have one piece of advice: WATCH OUT FOR THE TOPES! And I mean that sincerely!

The slideshow below contains an assortment of additional images from the four Puuc Hills sites that are featured in this post: Tacob, Sayil, Labna, and Xlapac. There is also a segment featuring pictures taken “On the Road” in Mexico. Those photos were taken by my shotgun rider, Michael Fritz (a.k.a. Mr. Whiskers).

Click on any photo to expand the images to full screen, with captions.

(Unless otherwise noted, all of these images are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.)

READ MORE LIKE THIS:

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

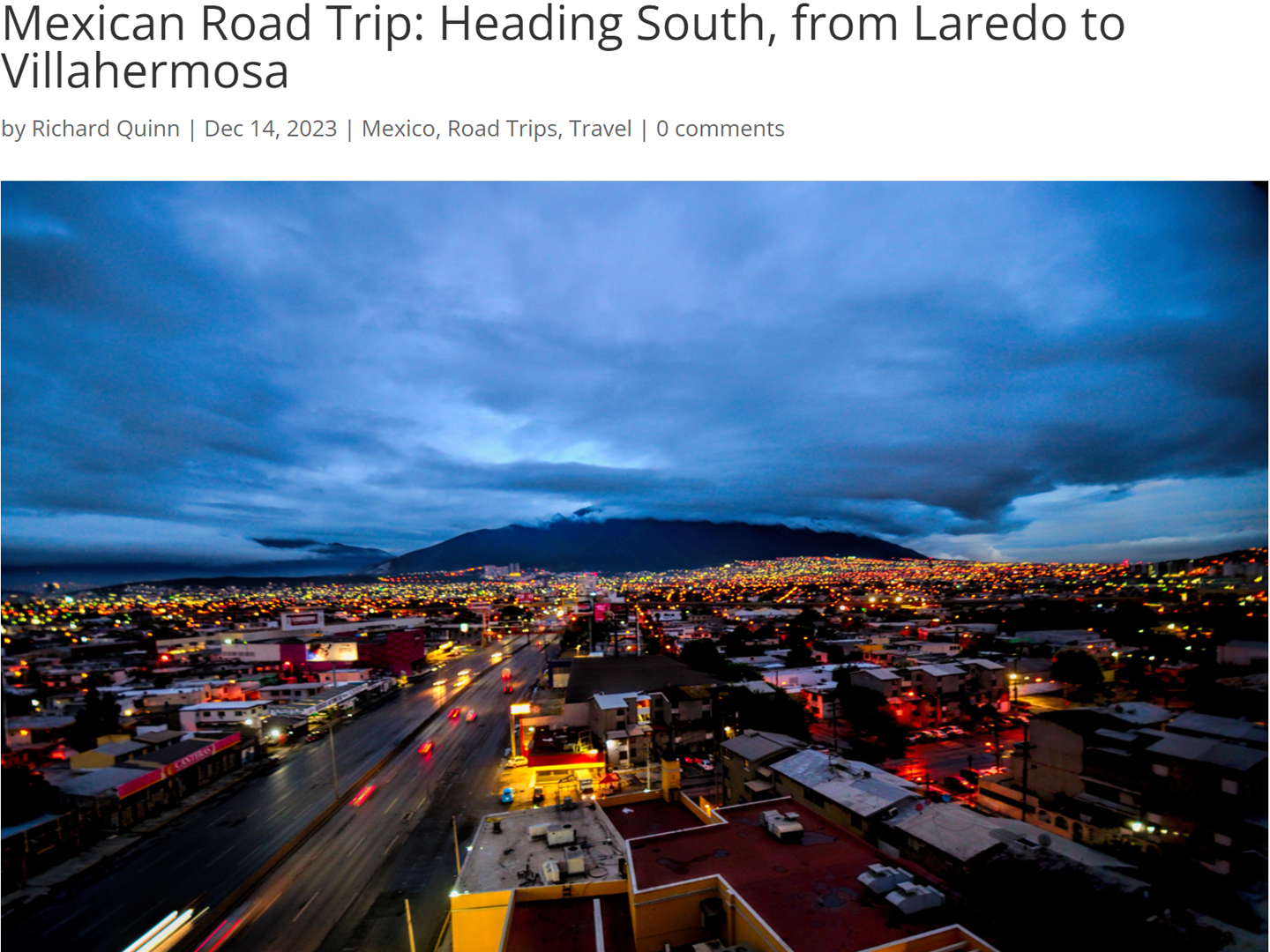

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

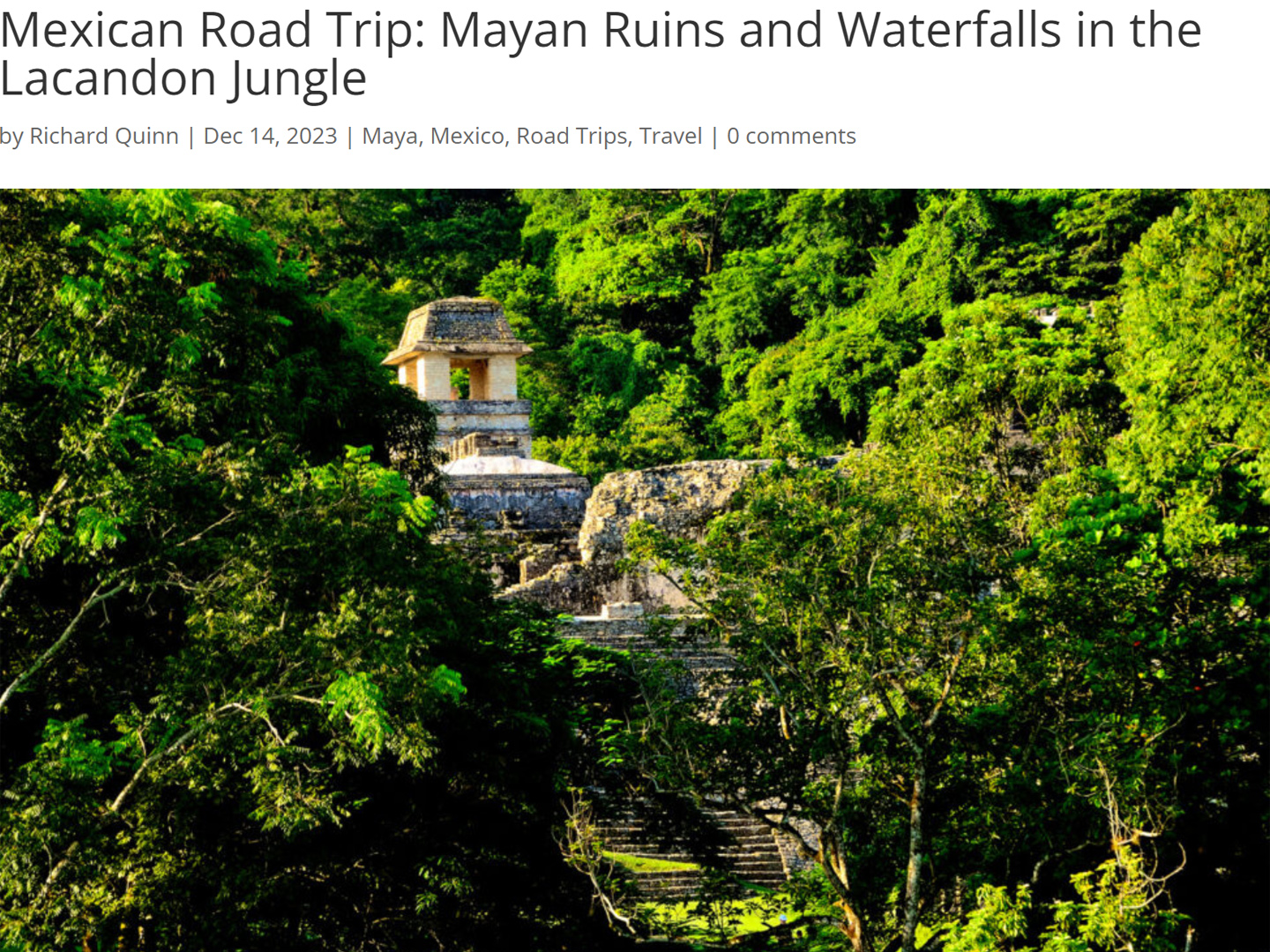

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

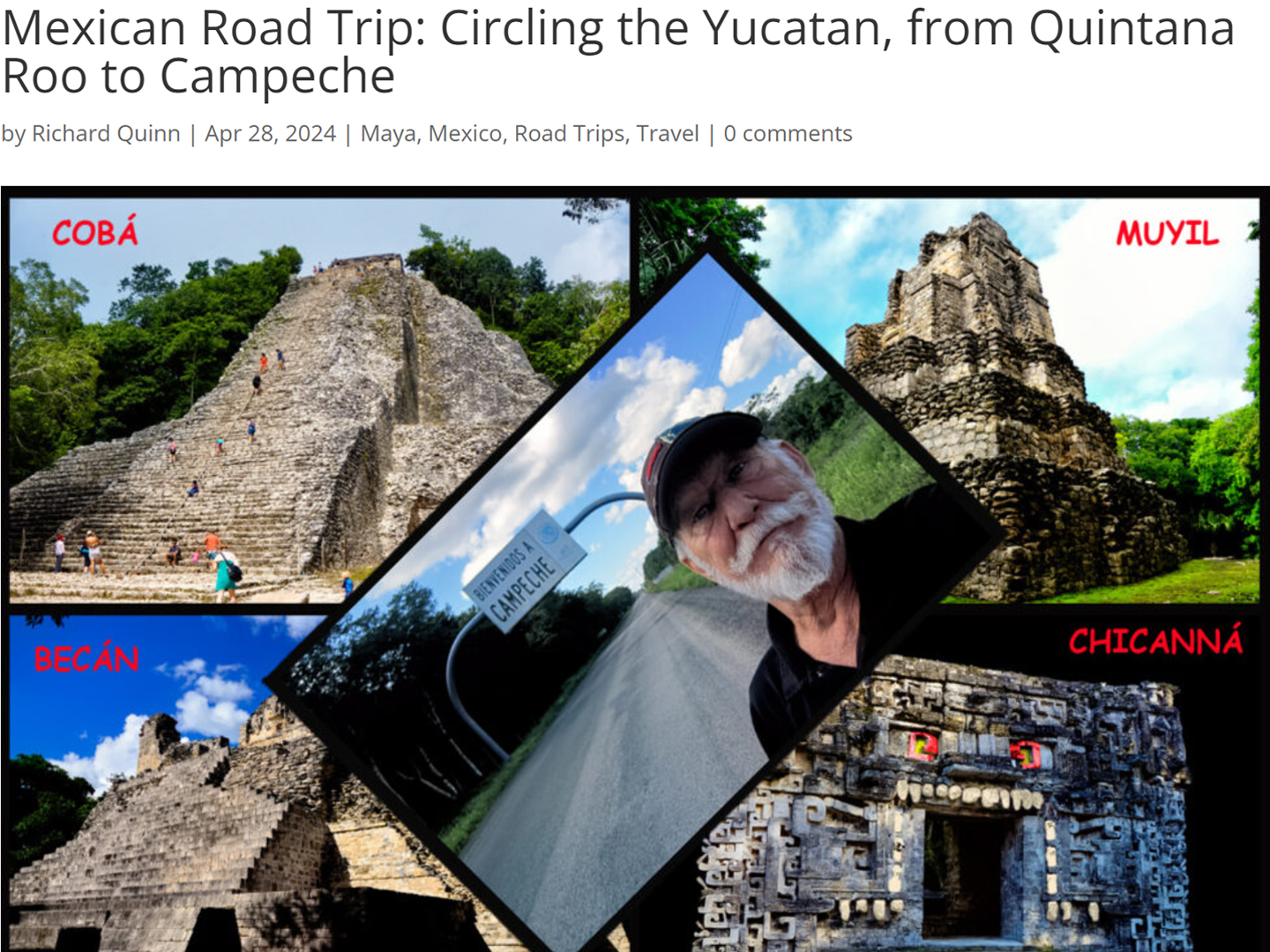

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn’t huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

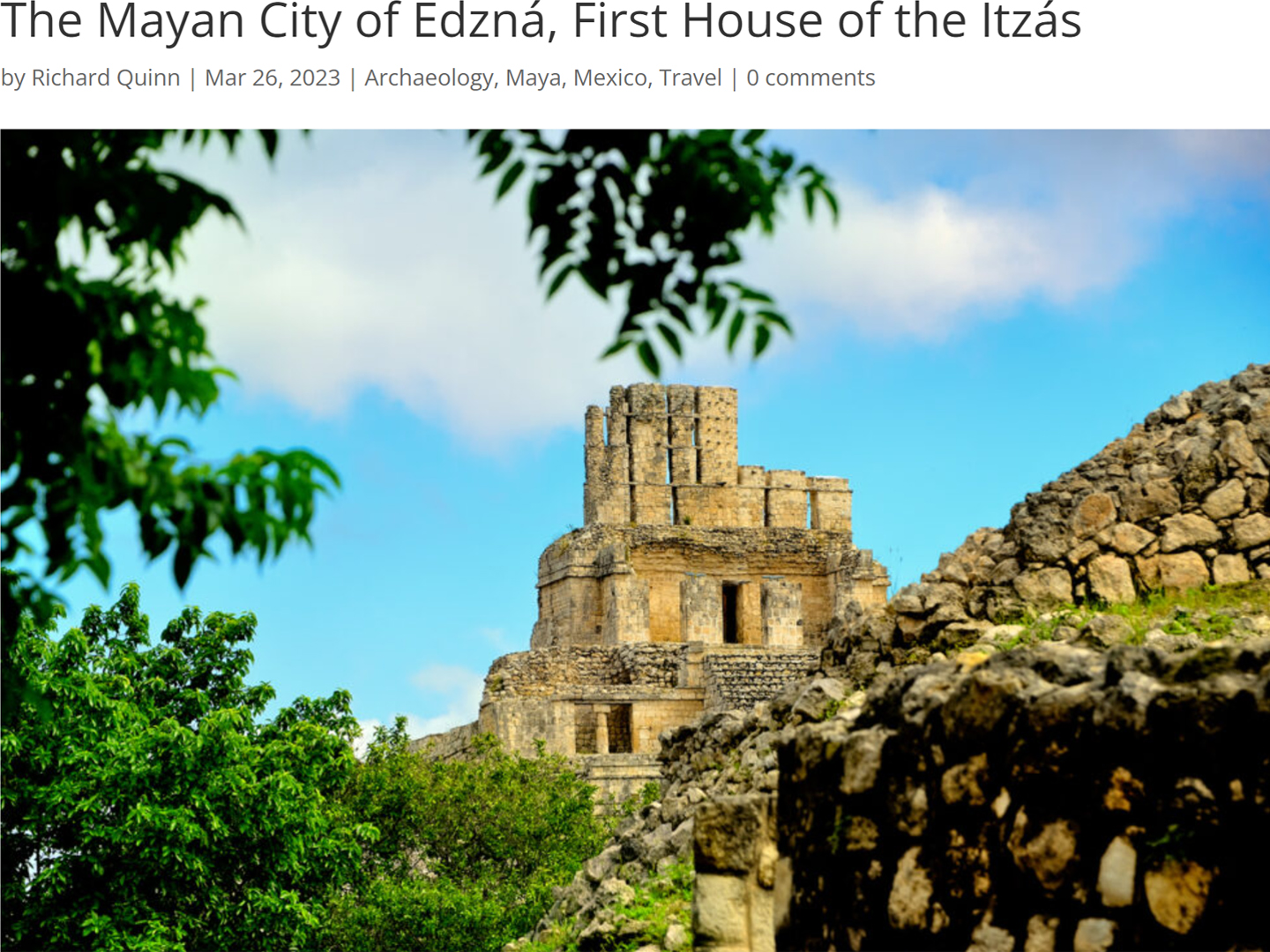

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

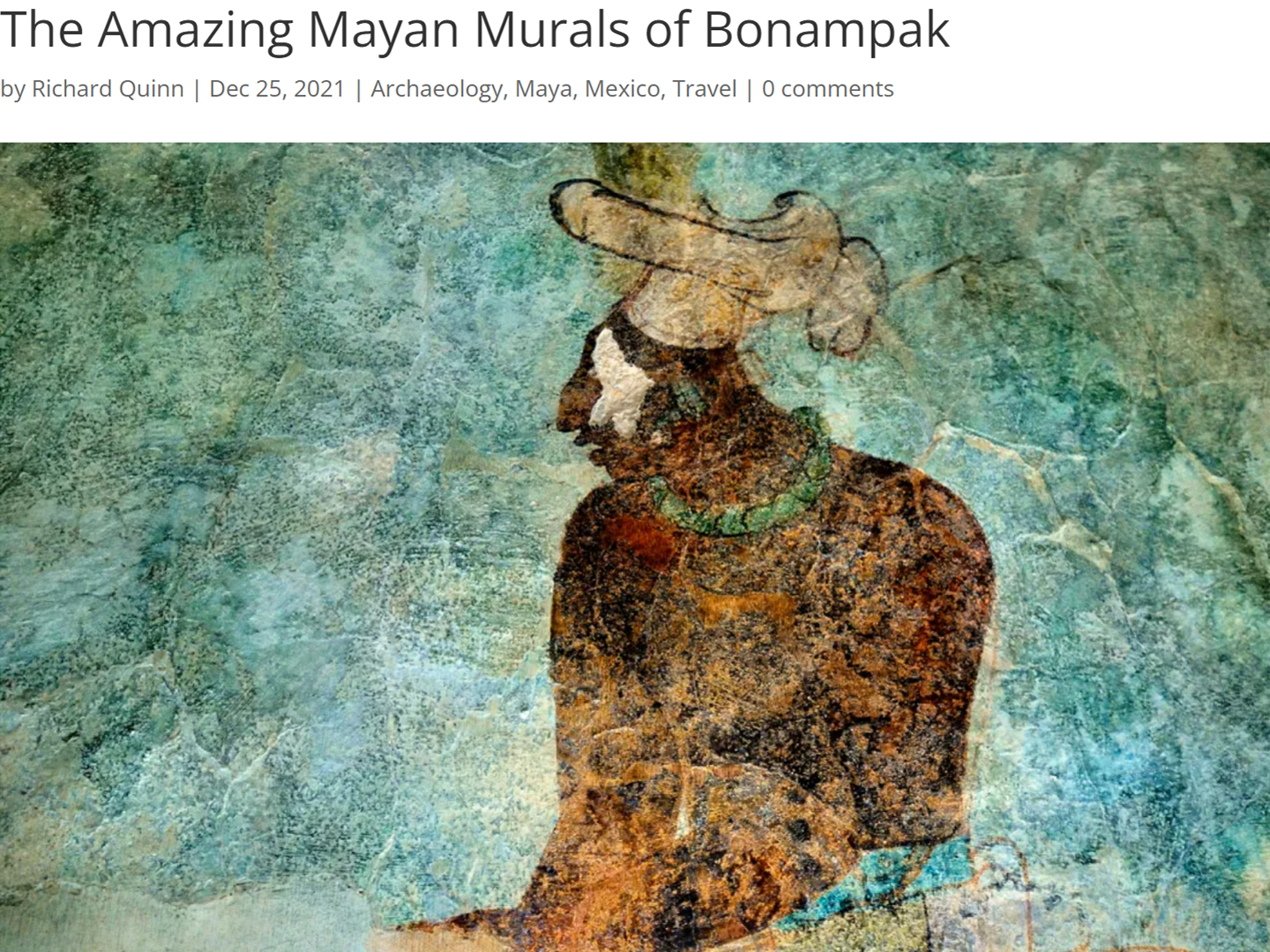

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

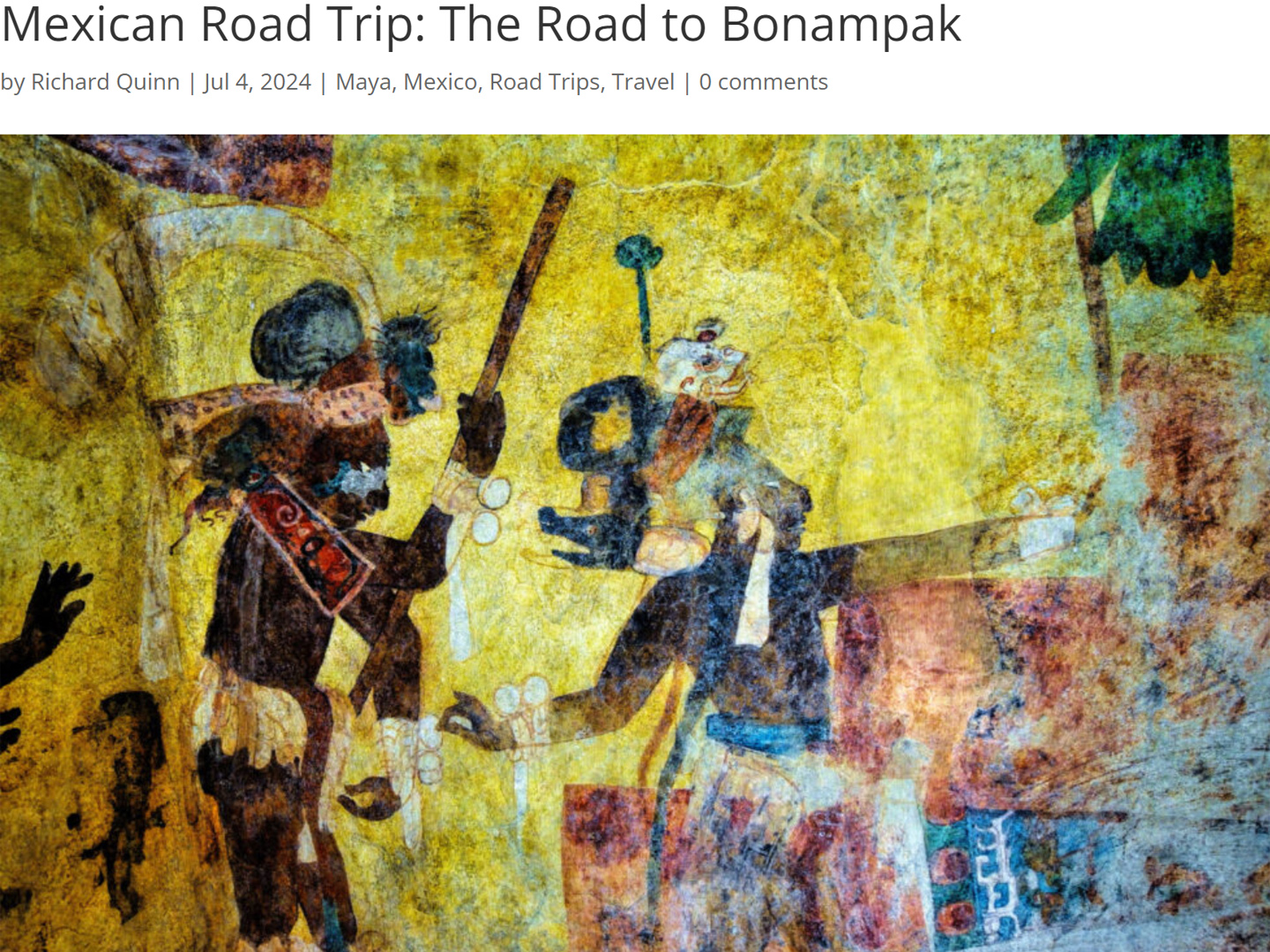

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we’re left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

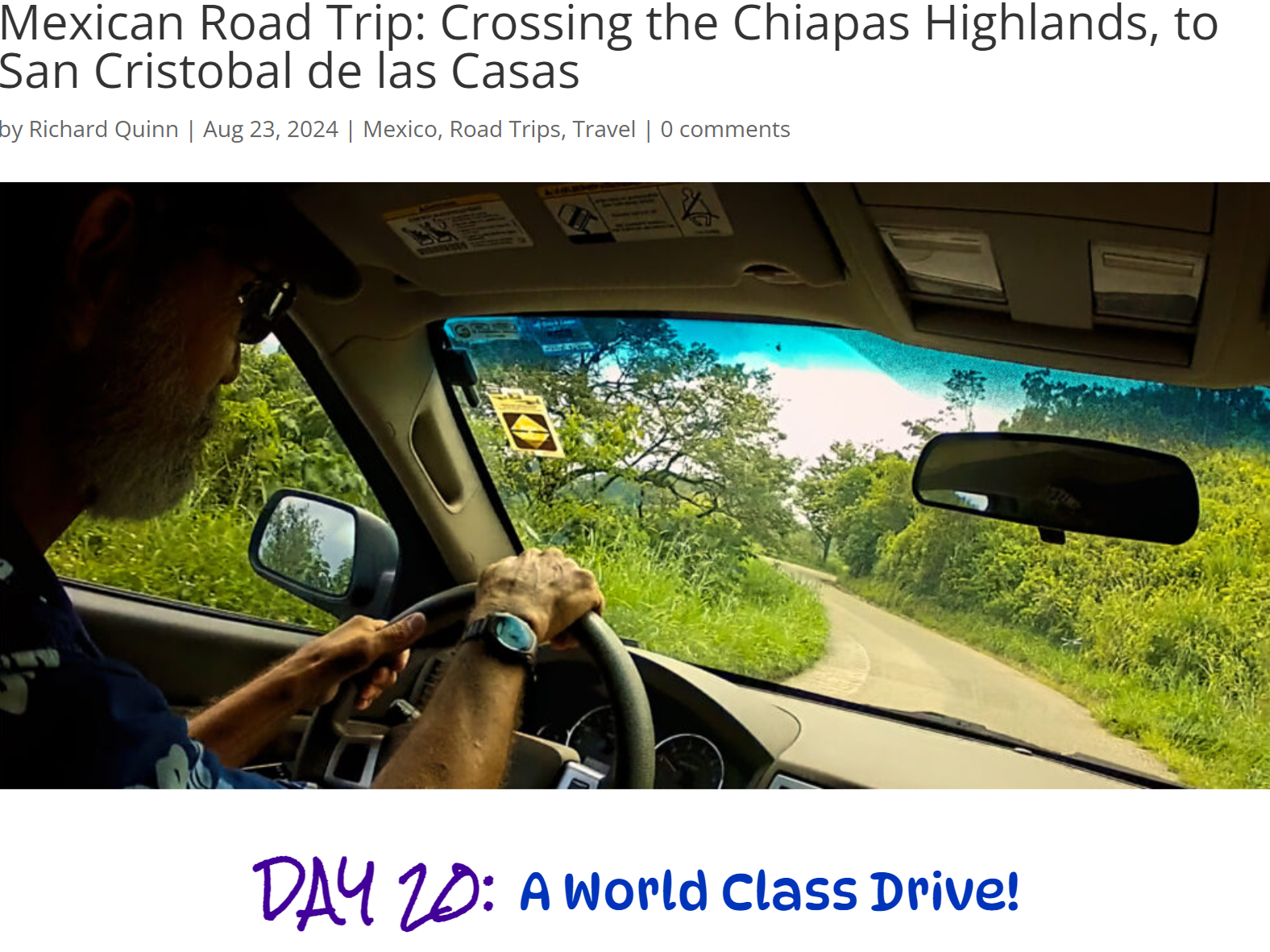

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it’s 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in November, 2024.

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in November, 2024.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in December, 2024.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

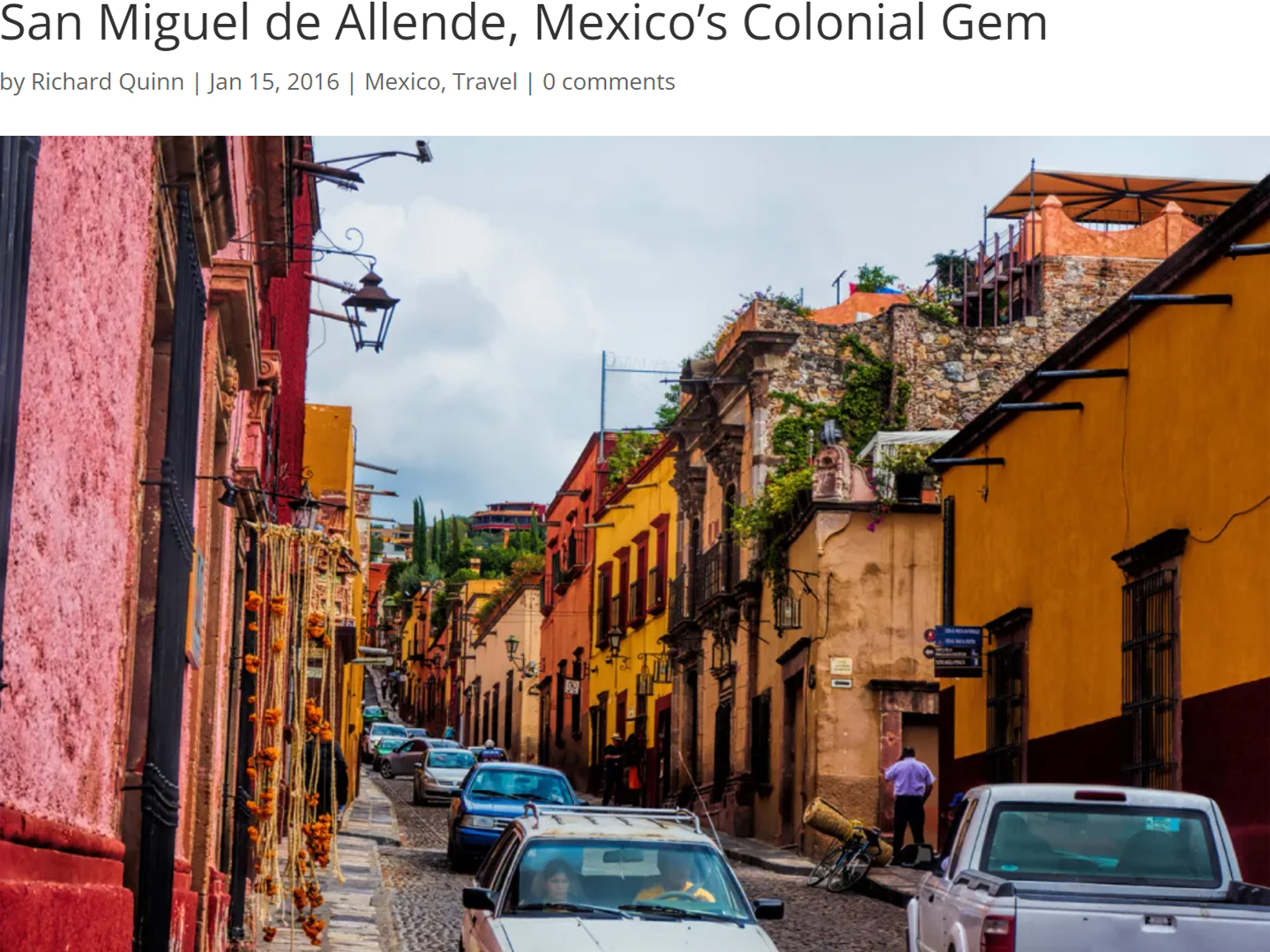

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico’s Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they’ve adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It’s a wonderful, colorful parade that’s all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

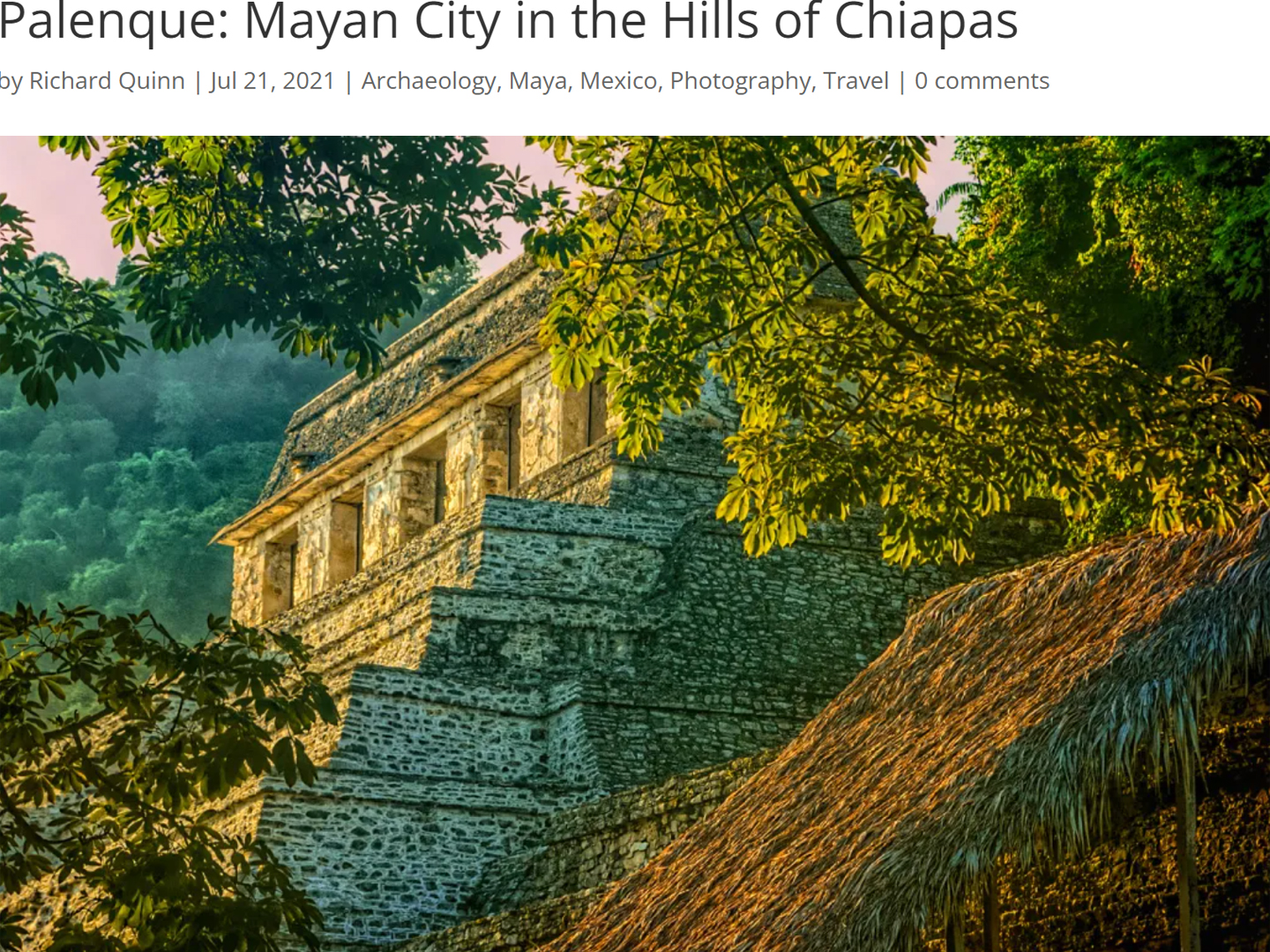

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

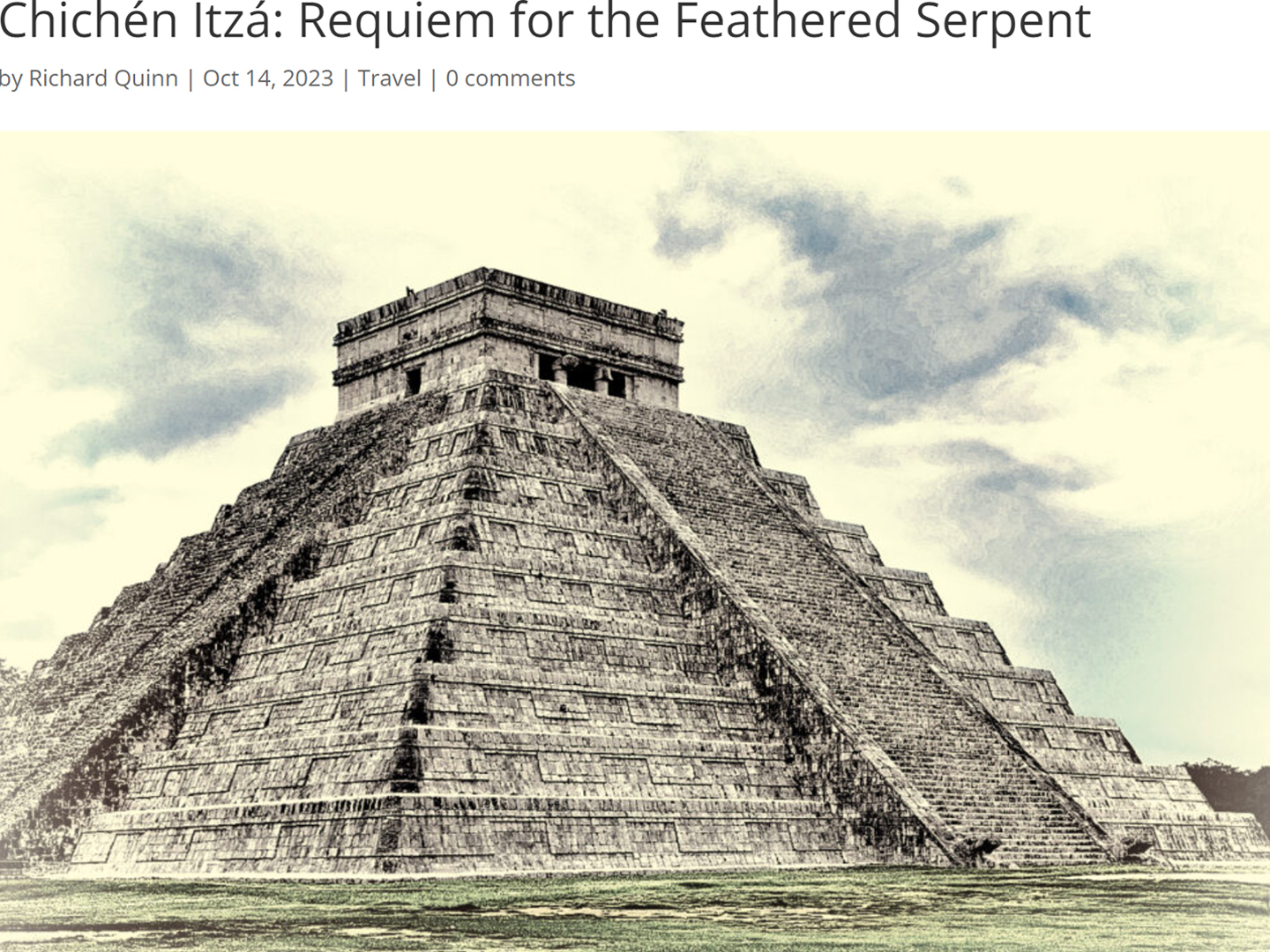

Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

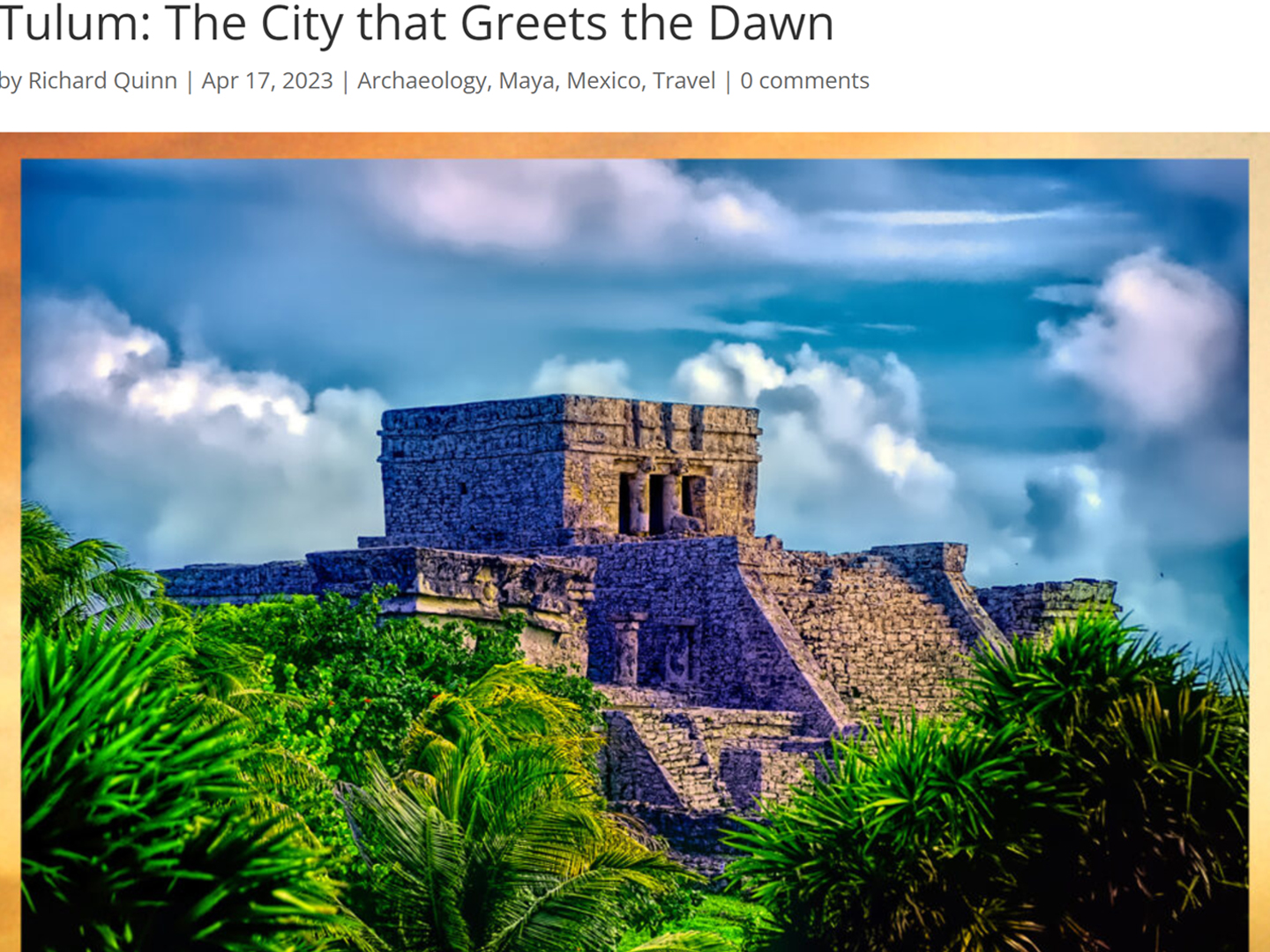

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

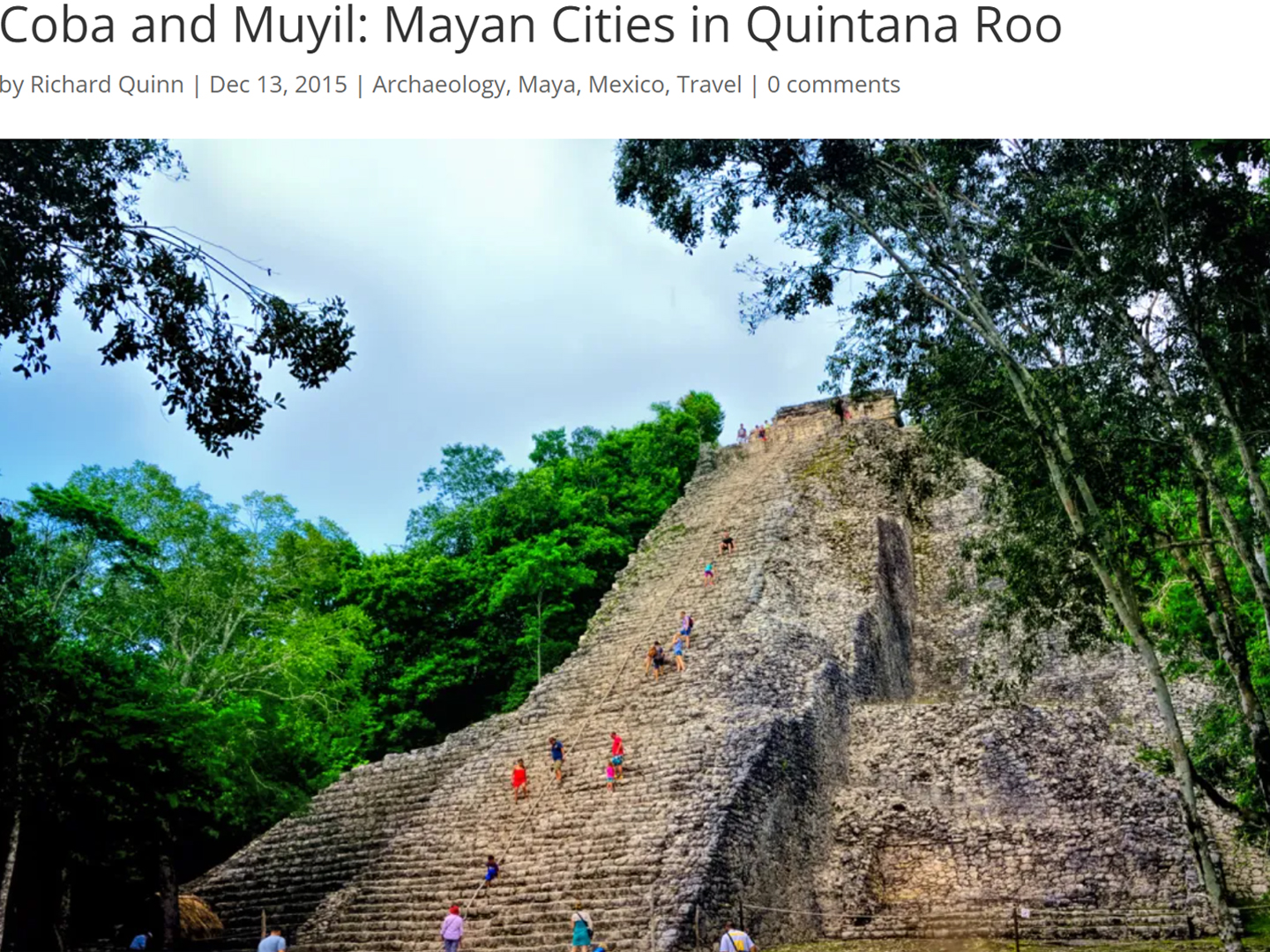

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

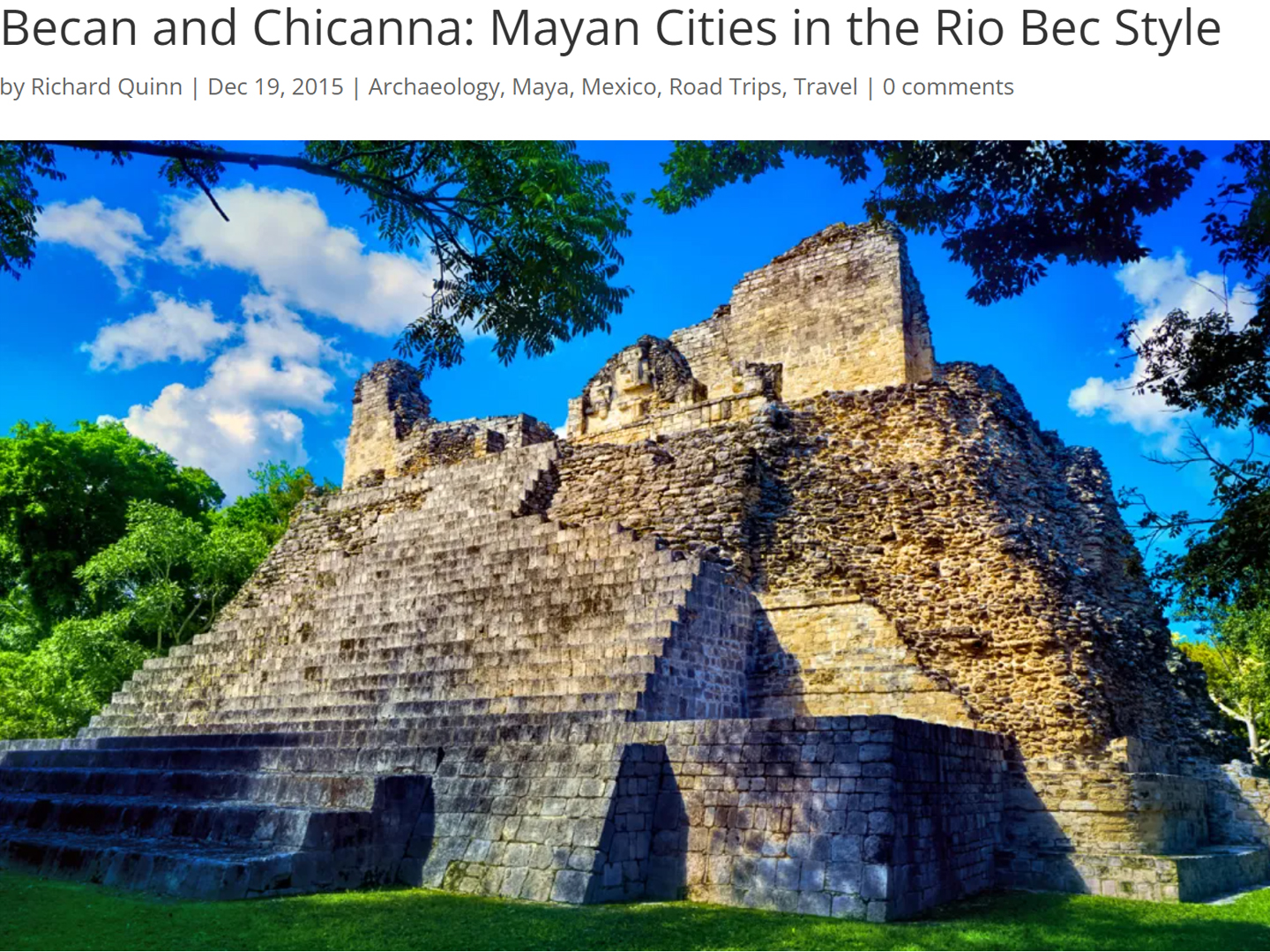

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. “Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins” was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after “Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali.” We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

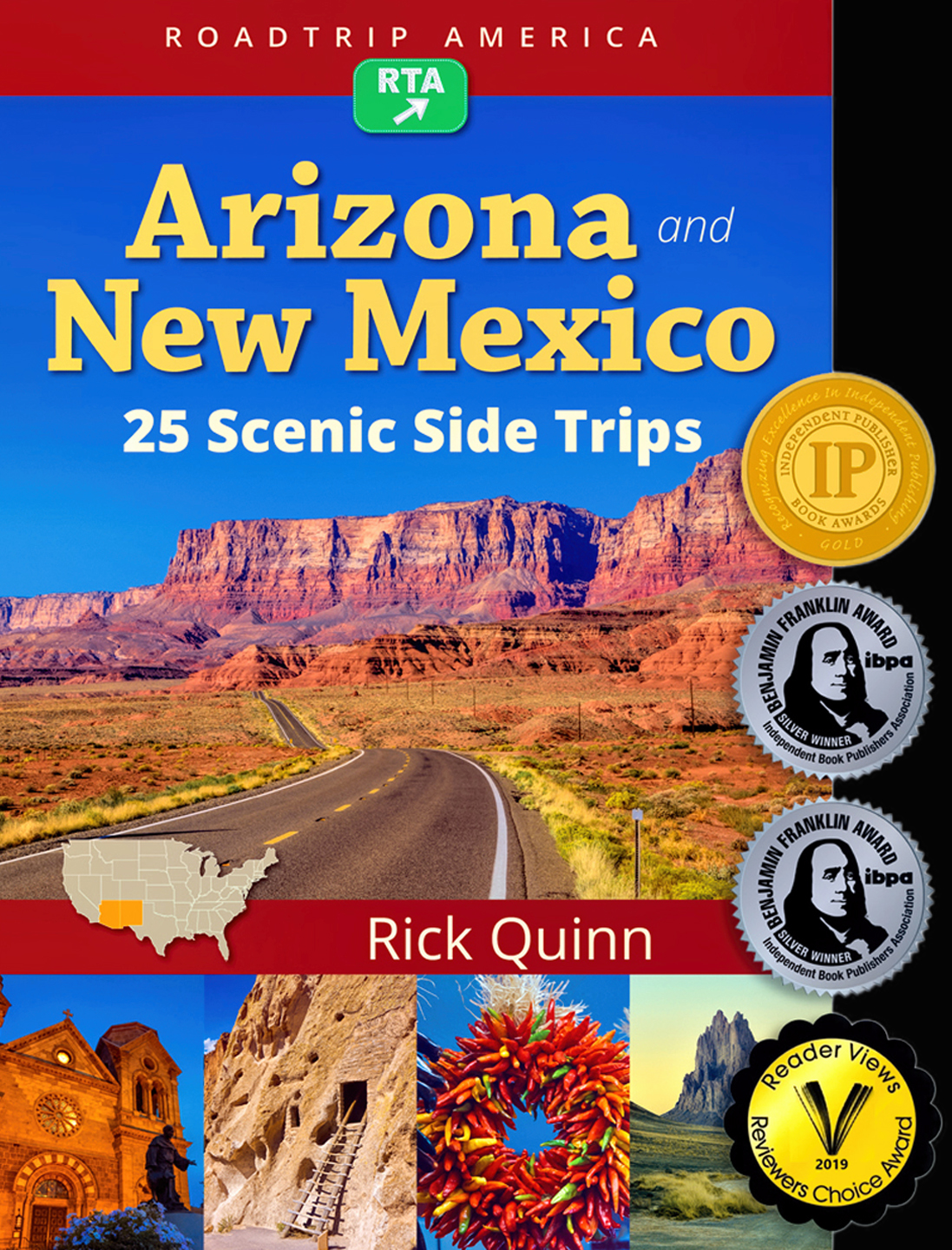

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments