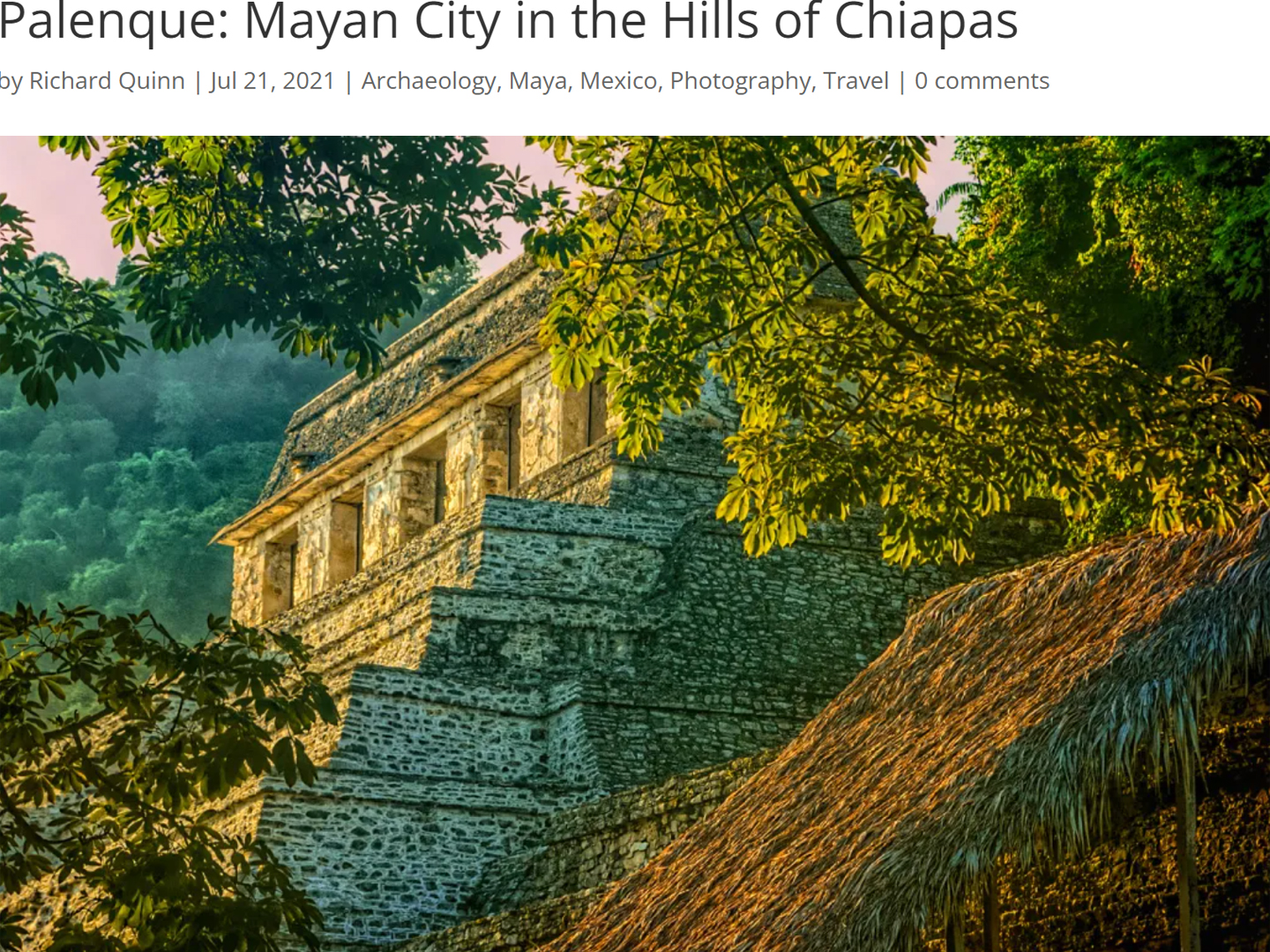

Palenque! This ruin of an ancient Mayan city, located in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, ranks among the most famous archaeological sites in the entire world. Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the Lacandon jungle. the remnants of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

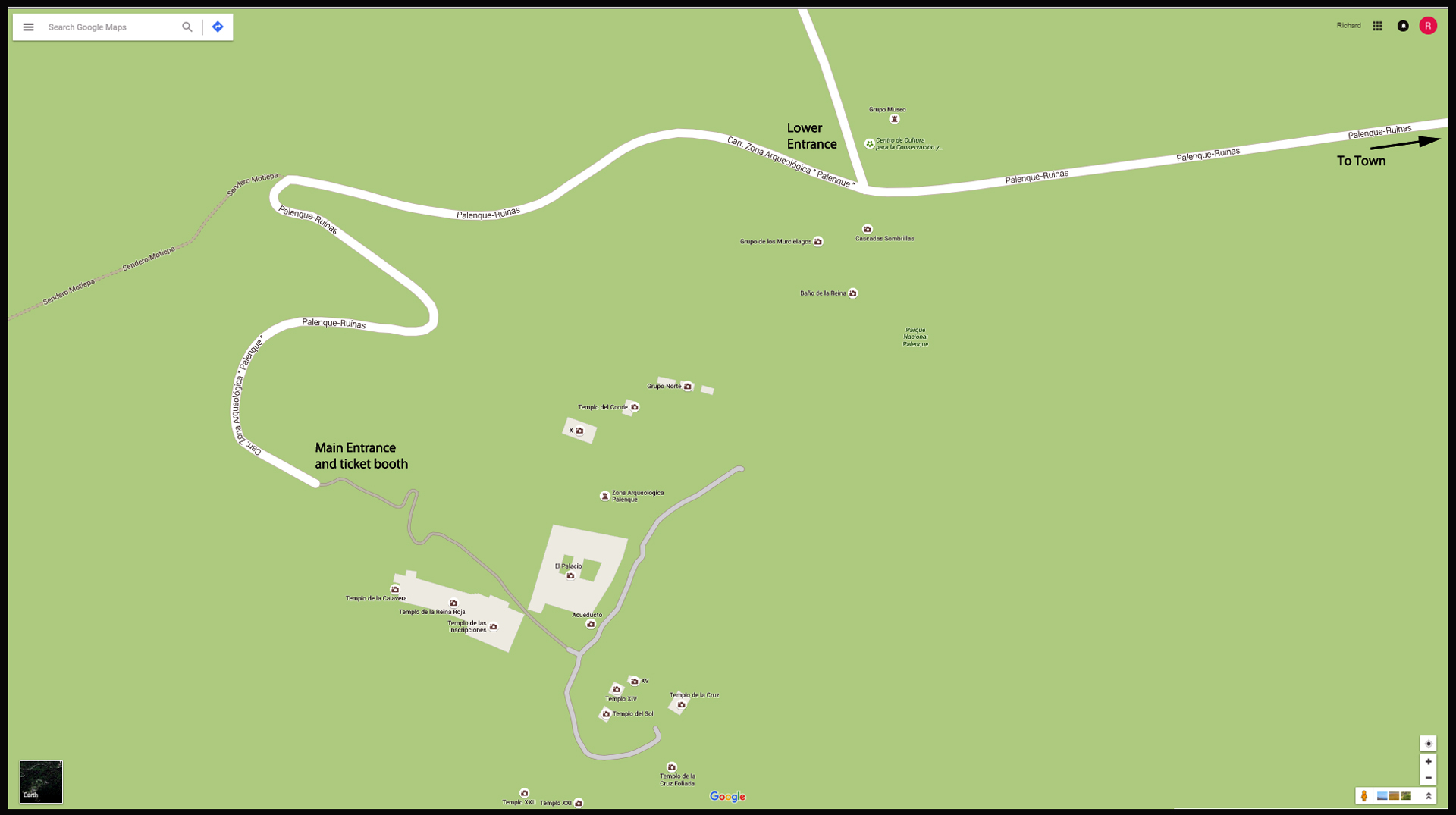

Click any map or photo to expand the image

HISTORY OF PALENQUE

The ruins of this ceremonial center, called Báak’ by it’s original inhabitants, was indeed a part of that forest, abandoned by the Maya and hidden from the world by that jungle for nearly 1,000 years, before it was “discovered” by a Spanish priest named Antonio de Solis in 1746. Tales of Palenque were quite the rage in Europe at one time, with many theorizing that the ornate constructions were the work of the Egyptians, or the lost tribes of Israel. Or perhaps this was a remnant of lost Atlantis!

Those fantasies were all long since debunked, once it became clear that that the builders of these architectural marvels were none other than the ancestors of the same people who live in the area today.

The modern Maya, peaceful subsistence farmers who eke out a meager living in relatively primitive conditions, maintain the same language, cultural heritage, and the same basic religion as the mighty warriors and pyramid builders of old. What’s missing today is the despotic ruling class, the kings and the nobles, and the fierce fighters that did their bidding. The major preoccupation of those ancients was war, for the express purpose of taking captives. The captives were a vital commodity: they provided the slave labor necessary for the building of all those monuments, and as fodder for the mill of human sacrifice demanded by a bloodthirsty priesthood.

Their predilection for barbaric sacrifice notwithstanding, the Maya nobility, at Palenque, and at the many other Maya sites throughout Central America, were learned men, and the Maya civilization, over the course of centuries, made significant advances in the fields of mathematics and astronomy. Calculations and sightings based on their observations worked in conjunction with extraordinarily precise alignment of the architectural elements in their temples, and, along with the famous Mayan calendar, enabled accurate forecasting of seasonal cycles for the planting of crops.

The Maya were an advanced and creative people who built utilitarian infrastructure along with the temples and ceremonial plazas. They constructed roads, and granaries, and water distribution systems consisting of aqueducts and cisterns. The soil was not rich, but they devised a system of crop rotation that enabled ample crop yields, enough food to support a population that, at the height of the classic period, was estimated to have been larger than the population of that same area today. Life was relatively good for the classic Maya–but that good life was enabled, at least in part, by bloodshed and human misery.

Palenque is not the greatest, or the most important of the Maya cities. It’s just middling in size, and there are numerous other sites with far more spectacular buildings. Even so, Palenque continues to stand out. It was among the first of the Mayan cities to come to the attention of the outside world, and to this day it is one of the most thoroughly and extensively studied. For that reason we know a fair bit about the place, and the story fairly oozes mystery and intrigue.

First settled as early as 100 BC, this remarkable complex of limestone buildings and pyramids reached its apex of development between 600 and 800 AD, under the reign of the great ruler K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, usually referred to as simply Pakal. He lived an extraordinarily long life for a man in his era, ruling his kingdom for 68 years, beginning at the age of 12. After his death at the age of eighty, in 683 AD, he was succeeded by his son, K’inich Kan B’alam, who reigned for nearly two decades, until he in turn was succeeded by his brother, Pakal’s other son, K’inich K’an Joy Chitam II. This dynasty of three kings held sway in Palenque for nearly a century, altogether, and they were responsible for the vast majority of the impressive monumental buildings that have survived to the present day.

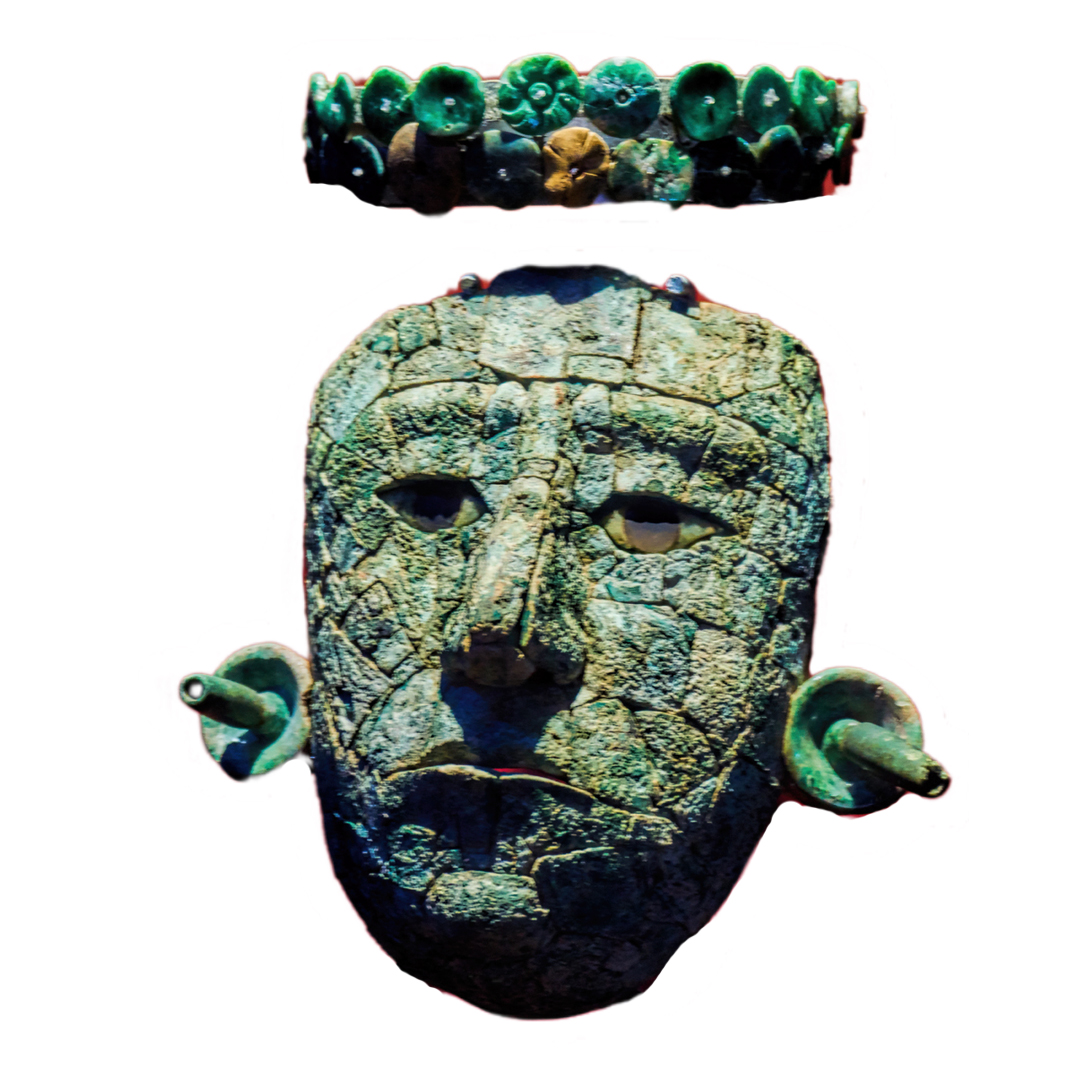

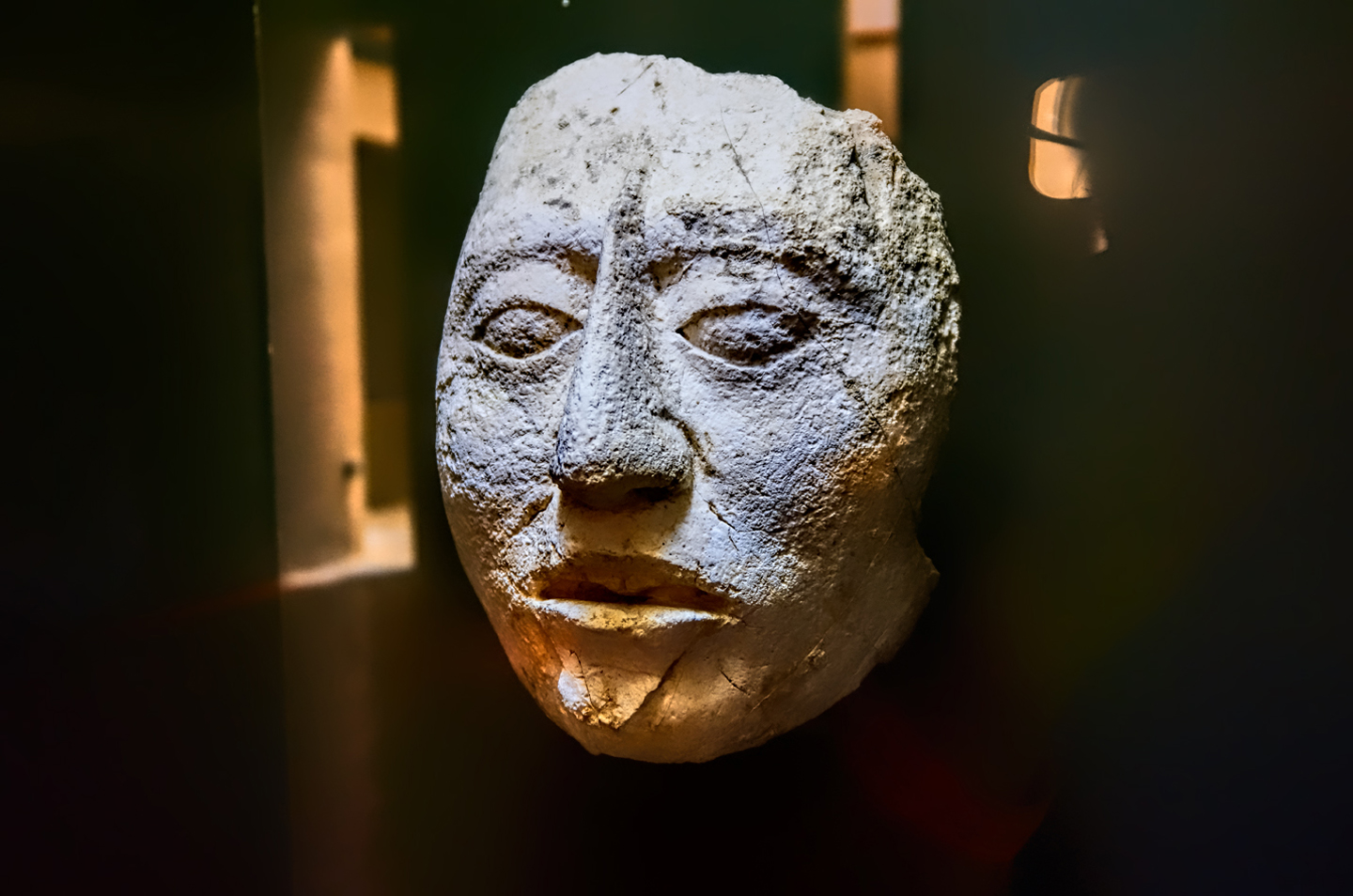

When Pakal died, his remains, encased in an armor of carved jade segments held together by gold wire, were entombed in an opulent sarcophagus deep within the massive pyramid known as the Temple of the Inscriptions, the tallest and most impressive of the many buildings in the ancient city. The discovery of that tomb, in 1952, was one of the premiere archaeological triumphs of the 20th century.

Beginning a hundred years after Pakal’s death, by around 800 AD, the complex social dynamic that made pyramid building possible began to come unraveled. The period of monumental construction ceased, and within a generation or two from that point, the ceremonial center and palace complex was abandoned altogether, and was, in fact, swallowed by the surrounding jungle. We don’t really know for certain what happened there. Perhaps the population overshot the capacity of the region to support it–not enough good soil to produce the volume of crops required. There may have been climate change, triggering an extended period of drought, or socio-political upheaval that undermined or deposed the ruling class. None of those possibilities has been proven to the exclusion of the others, so it’s probable that the abandonment of Palenque and the other Mayan sites in the lowland areas of the Yucatan resulted from a combination of such factors. The cause of the apparent collapse of this once great civilization is one of the abiding mysteries of our age.

VISITING PALENQUE

On my own trip to Mexico back in 2015, Palenque was my first real stop, because it was the first Mayan ruin that I came to on my way south from the U.S. border. Palenque is not in the Yucatan proper–it’s in the hills of Chiapas, near the northern border of that state. That turned out to be unfortunate: Chiapas is home to the Zapatista movement, and Zapatista protests blockaded all roads leading to Palenque on the very day that we tried to go there. We made it anyway, after a fairly adventurous detour, which I recounted in detail in my previous post, Mexican Road Trip: 2015.

The forested hills of Chiapas

Click for an expanded view of the map, showing the location of Palenque.

The Palenque Archaeological Park, as it exists today. Click for an expanded view.

Palenque, the ruin, is separated from Palenque, the town, by a distance of about 7.5 kilometers. There are numerous options for traveling to the ruins: small vans called “combis” run every ten minutes during the day, and even full-priced taxis are quite reasonable. Word to the wise: in Mexico, you should ALWAYS negotiate your taxi fare before you set out, especially when there’s no meter in the cab! In our case we simply drove out to the park, which was easiest of all. You pass a number of hotels and a couple of restaurants on your way to the ruins, but the forest is lush, very dense, all around you, and the area feels quite remote. The first thing you come to is a ticket booth, where they collect a fee of about $2 per person, which is the fee to enter the Palenque National Park. (Note that this fee for the park is separate from the fee to enter the ruins). Next you’ll come to the lower entrance to the ruins. There’s a rather nice museum there, as well as a gate, but there’s no real need to stop here on the way in, no matter what the hustlers who line the road here might try to tell you. They’ll be hollering and telling you to pull over, offering you their services as guides, and some of them are fairly aggressive. I would recommend that you pass right by these guys. You can’t buy your ticket to the ruins at this entrance in any case–you’ll need to keep going to the end of the road, where the main entrance is located, and that’s where the real guides can be hired. Entrance to the ruins will cost you $3 per person, and an English speaking official guide will set you back a whole lot more than that–about $60 US for a two hour tour. (On the plus side, you can have as many as 7 people in your group, all for the same fee). The guides have insights that you won’t get from tour books–but you’ll have to decide for yourself if it’s worth the cost. Palenque was one of the few major sites that allows you to re-enter the ruins using the same ticket if you leave and come back on the same day. Many sites charge the fee anew every time you come through the gate, so it pays to check before you walk out. (Note: prices quoted were correct in 2015; they’ve all gone up a bit.)

There is very little parking available at the upper entrance to the ruins. There’s a row of roofed-over stalls alongside the road, used by vendors selling souvenirs and other merchandise, and there’s a row of parking spaces in front of the stalls. It’s not a pay parking lot, but the spaces are guarded by a group of guys who will guide you into an available space, and then offer to watch your car for a fee. This was not an official parking fee, and I had no legal obligation to pay them anything, but I went ahead and gave one of the guys 20 Pesos, if only as a gesture of goodwill. They also offered to wash my car (which it seriously could have used), but I elected to pass on that service, so I’m not sure what they would have charged.

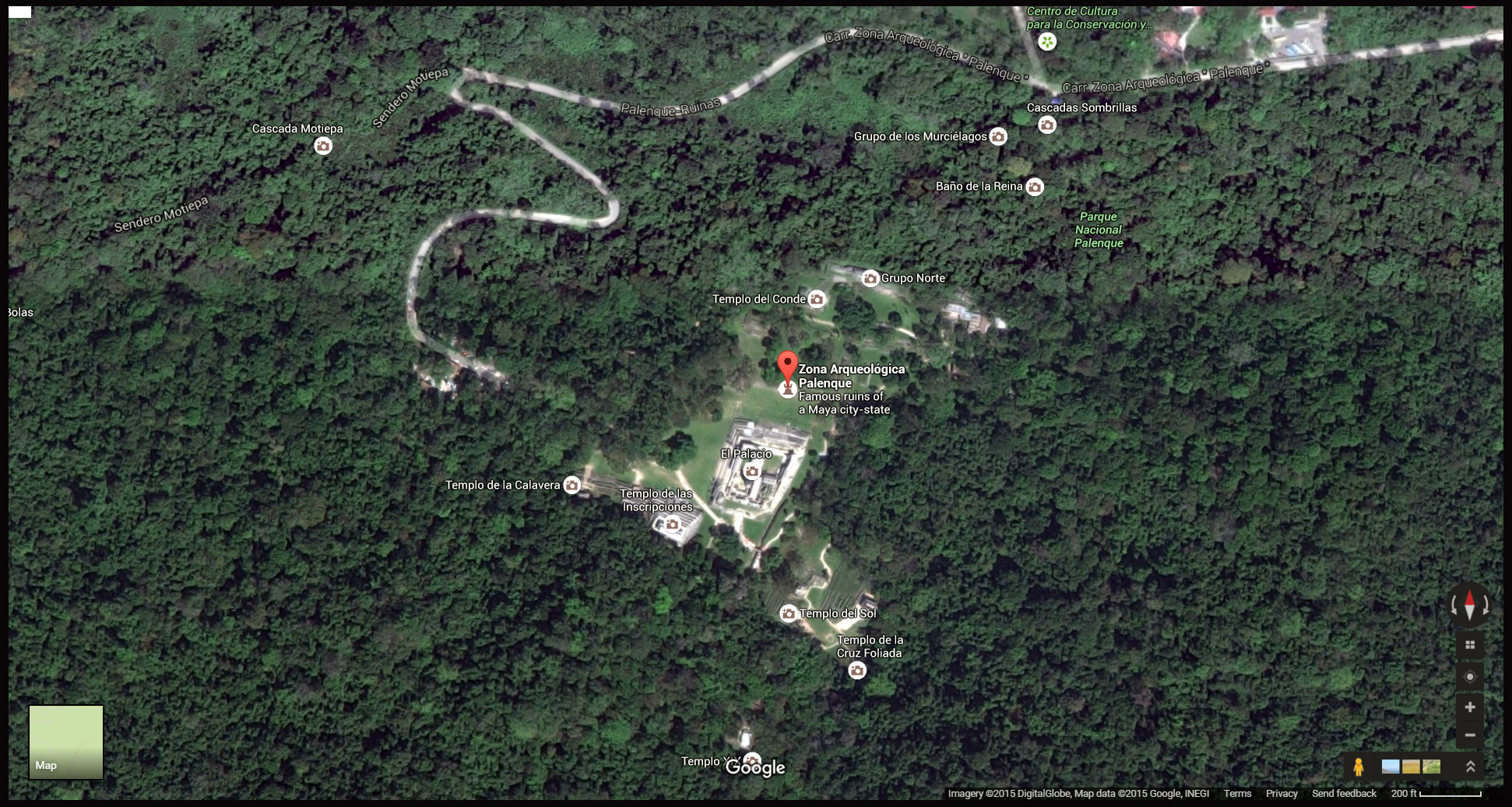

A satellite view of the Palenque Archaeological Park, showing the surrounding forest. It is estimated that there are at least 500 buildings associated with this magnificent ceremonial complex. The vast majority of these are still buried by the dense jungle. (Click for a larger view)

EXPLORING THE RUINS

When you first enter the park, a broad walkway leads you up a flight of wide steps, past more vendors selling merchandise, through a tunnel of trees to a large, open plaza. A crazily steep stone staircase rises up sheer on your right, leading up the side of a small pyramid topped by the ruins of a structure. This is the Templo de la Calavera, Temple of the Skull, so named because of a carving of a deer or rabbit skull at the base of one of the pillars.

Immediately adjacent is a slightly larger pyramid, the Tomb of the Red Queen. Right next to that, the soaring bulk of the magnificent Temple of the Inscriptions, the extraordinary mausoleum of the great King Pakal himself. In front of you, just to the left, is the massive palace complex with its utterly unique, four story observation tower.

More temples crown each of the surrounding hills, more pyramids are visible in the near distance, one after another. The overall impression can be overwhelming–my first glimpse of this incredible vista took my breath away, quite literally! I tried to imagine what this would have looked like to an ordinary Mayan peasant, more than a thousand years ago, seeing this for the first time. I knew what to expect, and I was still blown away!

Palenque is one of the sites where you can still climb on at least some of the structures. There are “do not cross” signs and ropes stretched across most stairways and doorways, the places where tourists are not allowed, so when there are no warning signs, you’re free to climb–at your own risk, of course. Walkways that have not yet been restored or stabilized can be dangerous.

Steps up some of the pyramids are deteriorating, so they’re not only dangerous, they’re in danger of being damaged by foot traffic. That’s truly a shame. It used to be possible to climb to the top of the Temple of the Inscriptions, and to then go down the steep stone steps into the heart of the pyramid, into the actual burial chamber.

The King’s body and his many treasures were removed and taken to Mexico City years ago, and a mock-up of the burial chamber was created as a thrilling exhibit in the National Museum of Anthropology. In the real burial chamber, there at Palenque, you could still see the massive, intricately carved lid of the King’s sarcophagus, which was left in place, along with extraordinary frescoes on the walls.

Sadly, visitors are no longer allowed to climb the pyramid, much less enter the burial chamber. The painted frescoes in the tomb are delicate, and the natural moisture brought in by visitors–exhaled in their breath–was beginning to cause irreversible damage. You’re still free to climb around in the Palace (though not in the observation tower), and you can also climb most of the smaller pyramids, which is great fun. There’s a technique to climbing a Mayan pyramid: the steps are very narrow, and the risers are quite tall, which makes the pitch of the stairs incredibly steep. For safety’s sake, and as a purely practical consideration, it’s best to stay parallel to the stairs, to keep your feet sideways on the steps, and to move diagonally upward as you climb. Your feet get a better purchase, and you’re less likely to slip. You don’t want to slip on one of those staircases. A fall down those steep stone steps could be a disaster.

Climbing about in the Palace is quite an adventure. There are passageways and interior staircases that lead you through a maze-like warren of rooms to four different courtyards at the center. The nearby river was re-routed beneath this complex to provide a source of running water–so the toilets were self-cleaning! In it’s heyday, extraordinary artwork proliferated on every surface: carved stone, formed plaster, painted frescoes, and most of the buildings were painted red. Even these crumbling ruins are dazzling. When it was actually in use, it would have been a wonder to behold.

After exploring the buildings around the main plaza, climb the hill to the southeast to check out the Grupo de las Cruces, the Group of the crosses, named for a cross-like carving on several of the buildings that actually represents the sacred ceiba tree, which, in Mayan cosmology, is the tree that supports the universe.

In the opposite direction, to the north of the palace complex, is the Grupo Norte, the North Group, which includes the Templo del Conde, the Temple of the Count, so named because of an eccentric European, Count de Waldeck, who literally lived atop the pyramid for two years while studying the ruins in the early 1800’s.

Beyond the North Group a path built with carved stone steps leads down into a lush, steep valley, the Arroyo Otulum. Additional buildings are scattered along the way, including the Grupo de los Murcielagos (Group of the Bats).

You’ll also see the Baño de la Reina, the Queen’s bath, a beautiful series of cascades tumbling over rocks in the stream. At the bottom of the path, you exit the lower entrance to the ruins, and at this point you can visit the small, but very good museum.

If you’re on foot, you can catch your ride back to town from here. If you drove, you can catch a ride back up the road to the parking area at the main entrance, or you can hike back up the steep path, back through the ruins.

My personal recommendation is to spread your visit to Palenque over two days. Start in the afternoon of the first day, and acquaint yourself with the layout. The next day, get to the site right at 8:00 AM, when the park first opens. You’ll have the place practically to yourself, and you’ll have the beautiful morning light, the very best for photos.

Since you’ll already know where you’re going, you can quickly make the circuit, first of the main plaza, and then the outlying groups of buildings, and you’ll get your pictures before the crowds arrive.

The slide show below contains an assortment of photos from the ruins and the surrounding area. Enjoy the pictures, and try to imagine, what it would have been like….

Note that this is an updated version of a previous post titled: Palenque: Palaces and Pyramids in the Land of the Maya

Unless otherwise noted, all of these photographs are my original work, and are protected by copyright. They may not be duplicated for commercial purposes.

Click any map or photo to expand the image

Palenque in 1970:

Original Photographs by Carl Duisberg

My good friend Carl Duisberg has been a world traveler almost as long as I’ve known him, and I’ve known him since we were both kids in school.

I recently helped him resurrect two dozen rolls of black and white film from some of his early adventures, negatives that had been packed away for half a century and essentialy forgotten. No prints were made when the film was first processed, all those years ago, so when I scanned and edited the images, I brought wonderful photos to life that had never been seen before.

One of those rolls of film was shot in the ruins of Palenque, more than fifty years ago, and Carl has graciously agreed to share them here. Viewing these old photos, it’s apparent how much work has been done cleaning up the ruin. In 1970, many of the structures you see today were still half buried, and the walkways for visitors were unpaved dirt paths. At that time, visitors were still allowed to climb the pyramid of the Incriptions, and enter Pakal’s burial chamber; one of Carl’s photos shows that view.

(If you’d like to see more of Carl’s work, check out the Historic Photos section of this website.)

READ MORE LIKE THIS

This is an interactive Table of Contents. Click the thumbnails to open the pages.

ON THE ROAD IN MEXICO

MEXICAN ROAD TRIP: HOW TO PLAN AND PREPARE FOR A DRIVE TO THE YUCATAN

The published threat levels are a “full-stop” deal breaker for the average tourist. That’s unfortunate, because Mexican road trips are fantastic! Yes, there are risks, but all you have to do to reduce those risks to to an acceptable level is follow a few simple guidelines.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

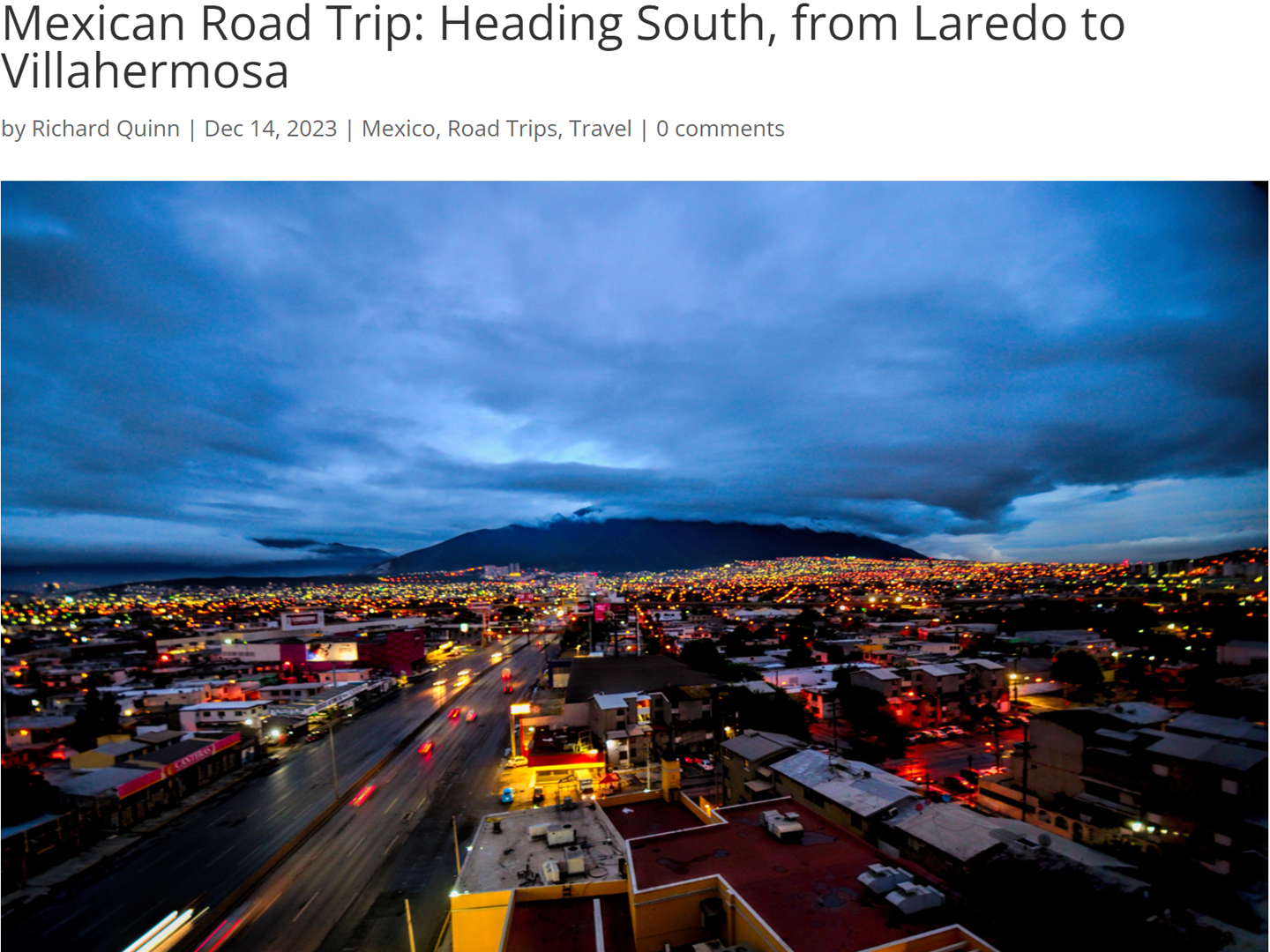

Mexican Road Trip: Heading South, From Laredo to Villahermosa

When it was our turn, soldiers in SWAT gear surrounded my Jeep, and an officer with a machine gun gestured for me to roll down my window. He asked me where we were going. I’d learned my lesson in customs, and knew better than to mention the Yucatan. “We’re going to Monterrey,” I said, without elaborating.

He checked our ID’s and our travel documents, then handed them back. “Don’t stop along the way,” he advised. “You need to get off this road and to a safe place as quickly as you can!”

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Zapatista Road Blocks in Chiapas

“Good morning,” I said. “We’re driving to Palenque. Will you allow us to pass?”

The leader of the group, a young Mayan lad, walked up beside my Jeep, and fixed me with a menacing glare. “The road is closed,” he said, keeping his hand on the hilt of his machete. “By order of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!”

“Is it closed to everyone?” I asked innocently. “How about if we pay a toll? How much would the toll be?”

He gave me an even more menacing glare. “That will cost you everything you’ve got,” he said gruffly, brandishing his machete, while his companions did the same.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

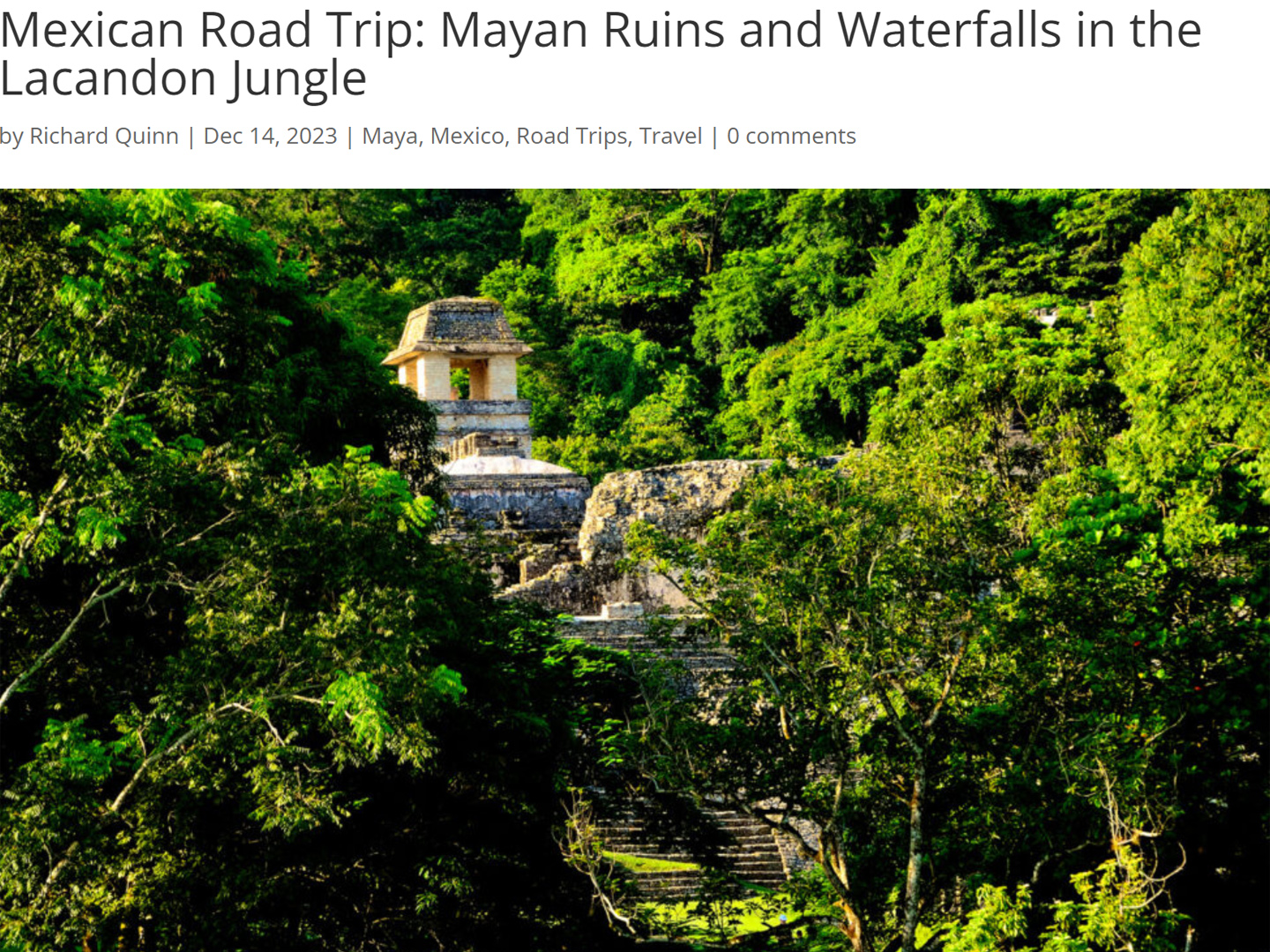

Mexican Road Trip: Mayan Ruins and Waterfalls in the Lacandon Jungle

The next morning, we were waiting at the entrance to the Archaeological Park a half hour before they opened for the day. We were the only ones there, so they let us through early, and I had the glorious privelege of photographing that wonderful ruin in the golden light of early morning, without a single fellow tourist cluttering my view.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Mexican Road Trip: Cancún, Tulum, and the Riviera Maya

The millions of tourists who fly directly to Cancún from the U.S. or Canada are seeing the place out of context. They can’t possibly appreciate the fact that they’re 2,000 miles south of the border; a whole country, a whole culture, a whole history away from the U.S.A. Just looking around, on the surface? The second largest city in southern Mexico could easily pass for a beach town in Florida.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

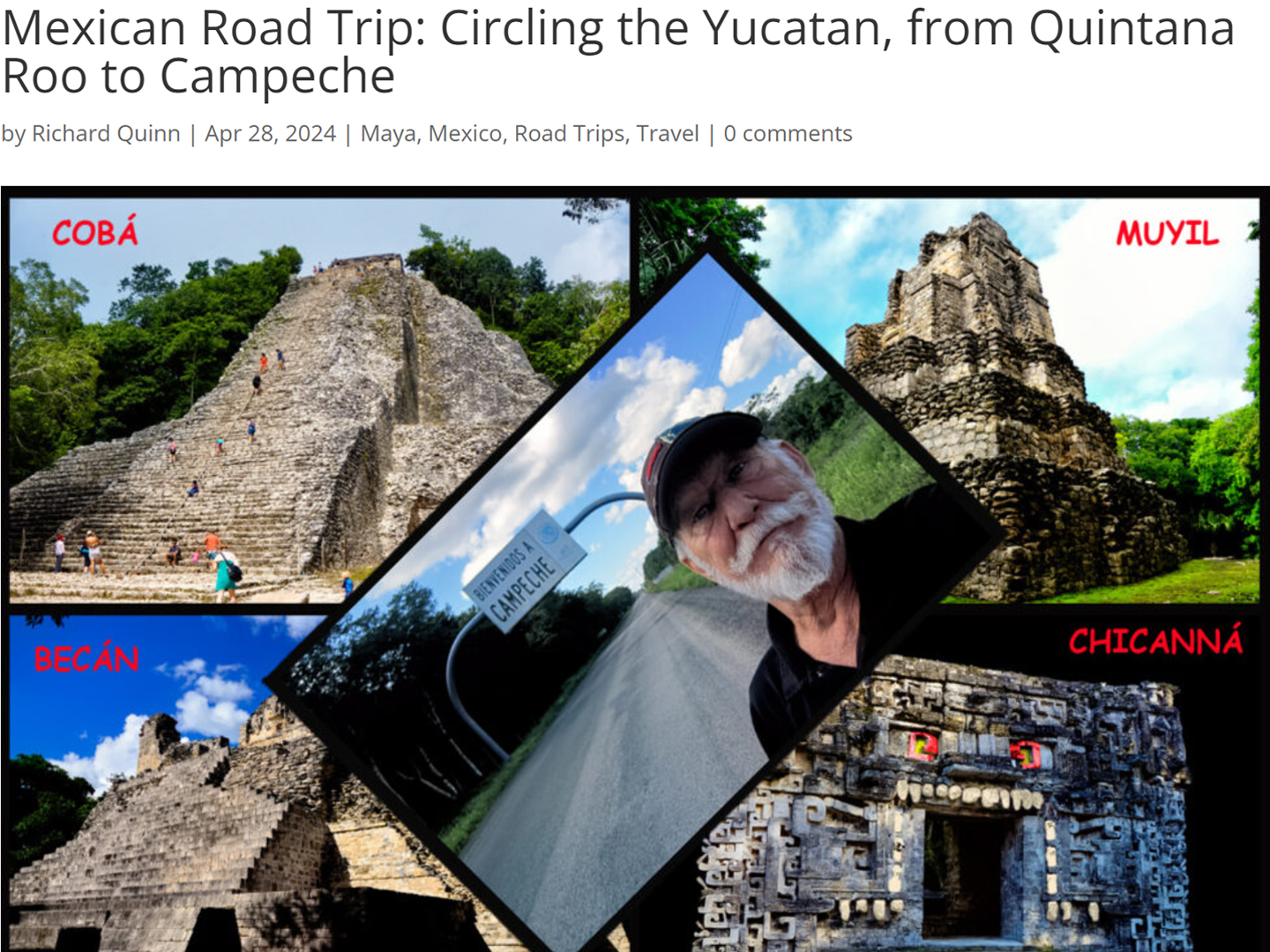

Mexican Road Trip: Circling the Yucatan, from Quintana Roo to Campeche

The Castillo at Muyil isn’t huge, as Mayan pyramids go, topping out at just over 50 feet, but it’s definitely imposing. Try to imagine: the equivalent of a five story building, with a three story grand staircase, just appearing, out in the middle of nowhere? Boo-yah!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

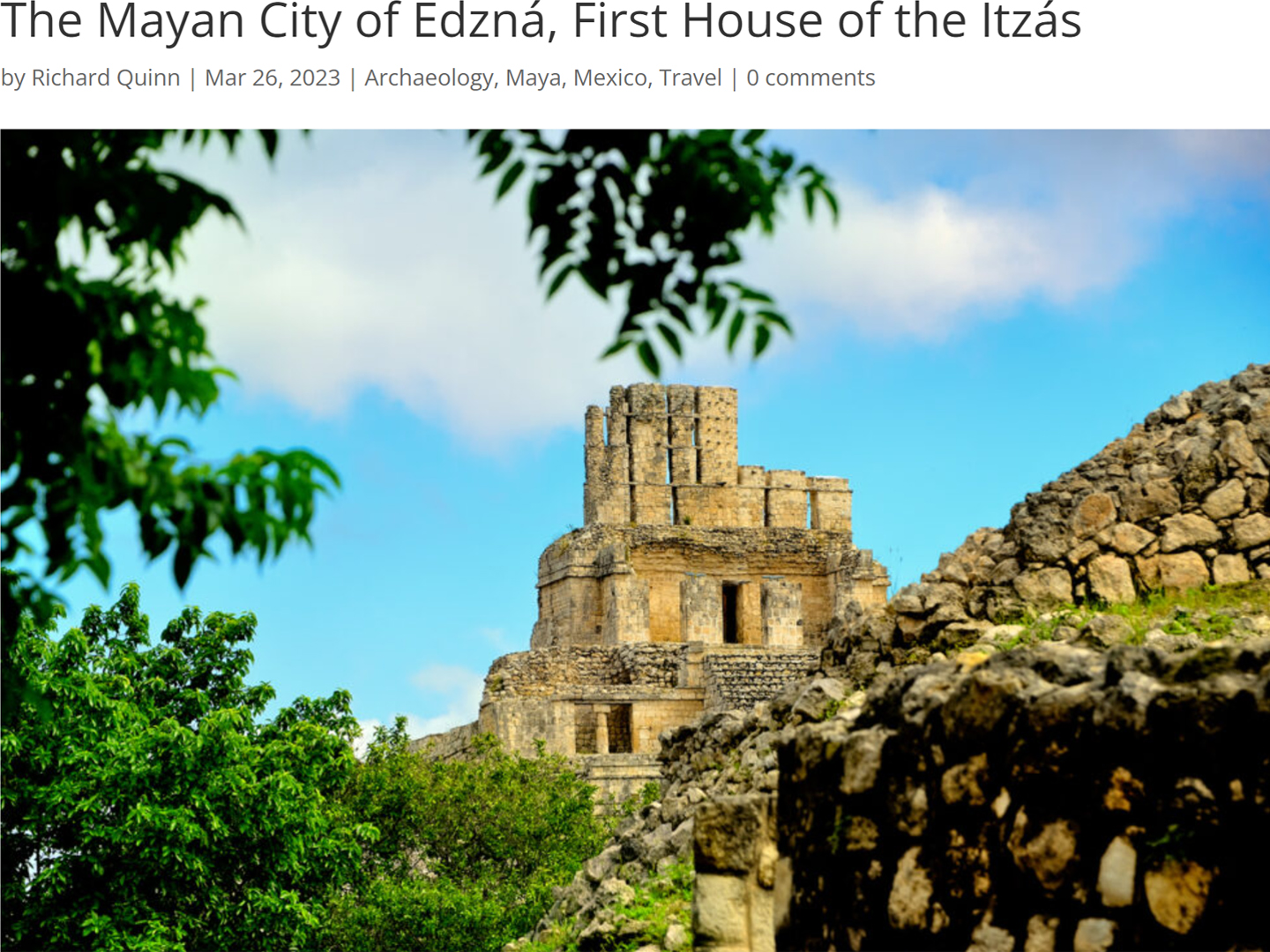

Mexican Road Trip: Edzná, and Campeche, Where They Dance La Guaranducha

La Guaranducha, a traditional dance from Campeche, is a celebration of life, community, and the joy of existence. On stage, there was a group of young men and women in traditional dress, but it was clear that the guys were little more than props, because all eyes were on the girls. So colorful, and so elegant, hiding coyly behind their pleated, folding hand fans.

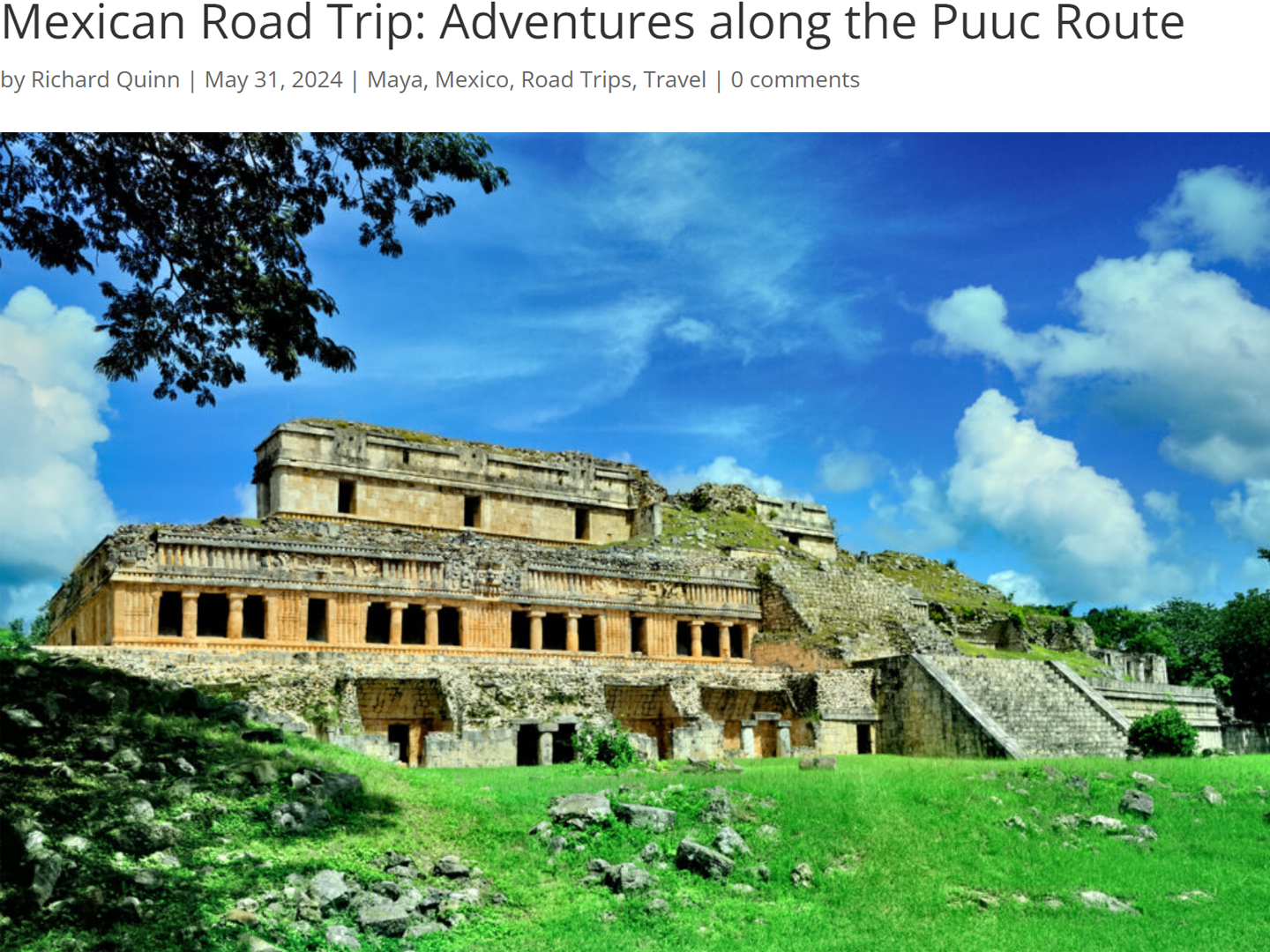

Mexican Road Trip: Adventures Along the Puuc Route

All of these communities in the Puuc region were allied, politically, culturally, economically, and socially. The Puuc was the cradle of the Golden Age of the Maya. Labna and Sayil were among the brightest jewels in the crown of a realm that never quite coalesced into an empire.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

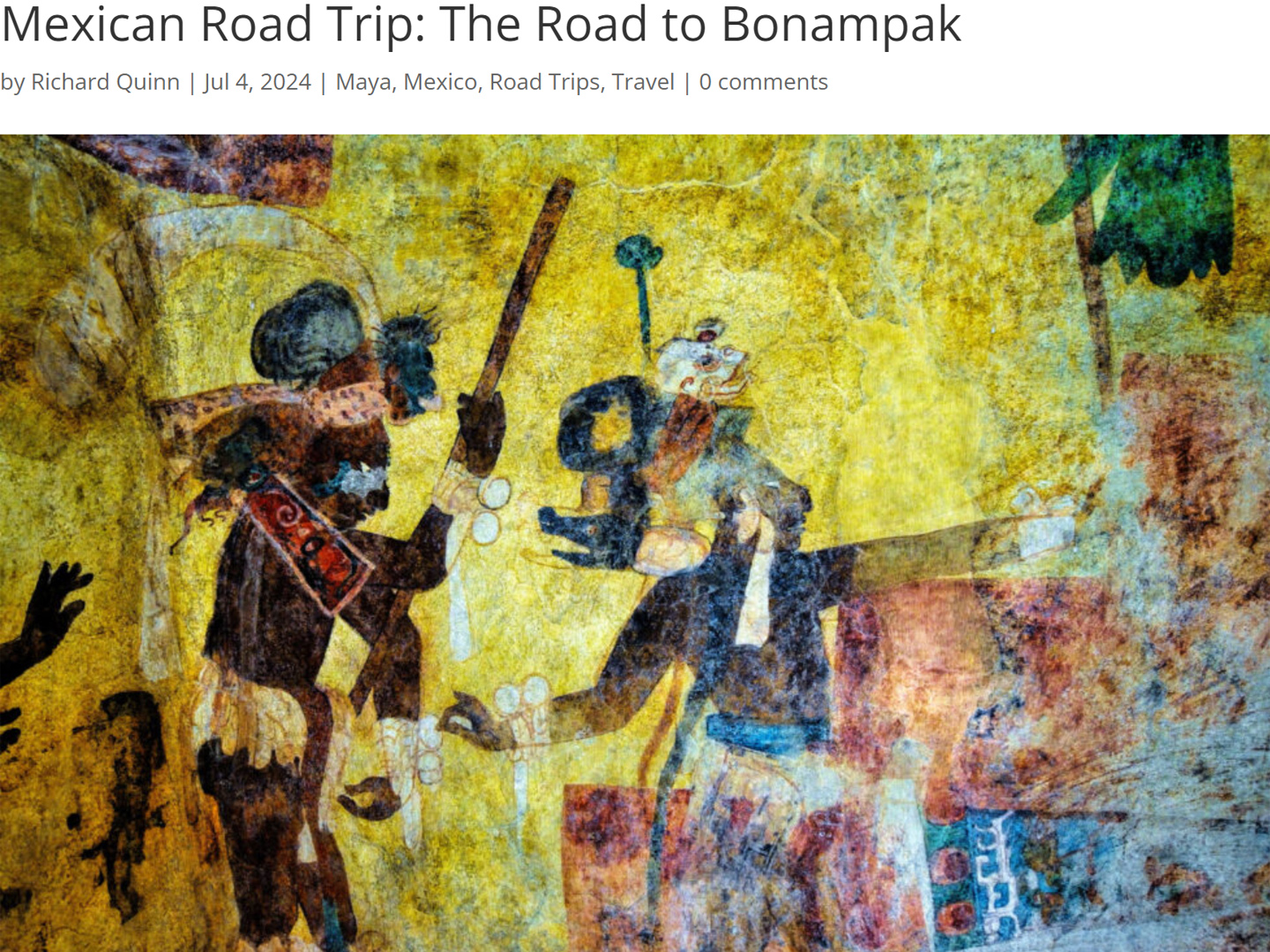

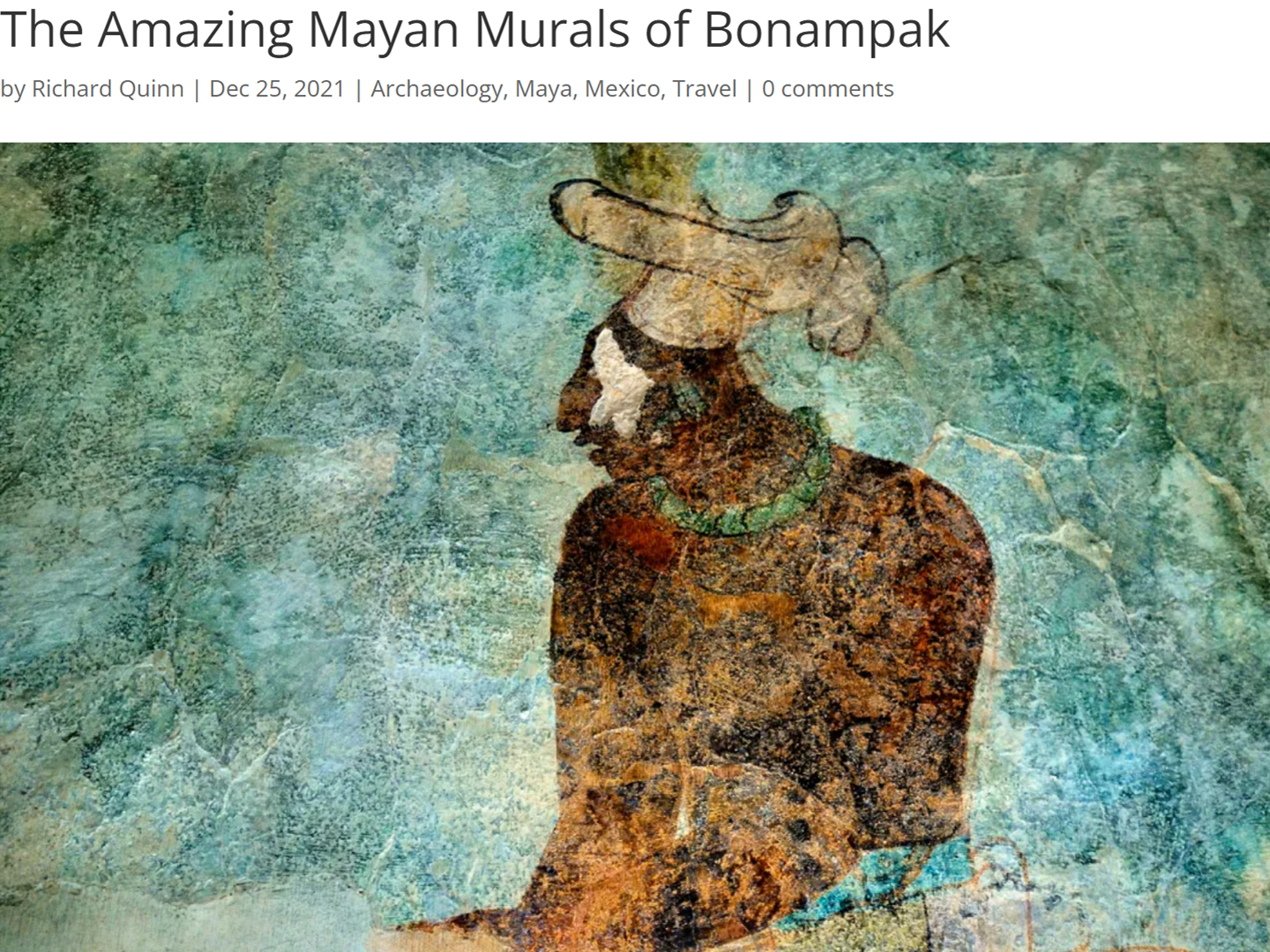

Mexican Road Trip: The Road to Bonampak

Rainwater seeping through the limestone walls of the temple soaked the Bonampak Murals with a mineral-rich solution that, each time it dried, left behind a sheen of translucent calcite. The built-up coating protected the paintings for more than 1200 years. As a result, we’re left with the finest examples of ancient art from the Americas to have survived into our modern era.

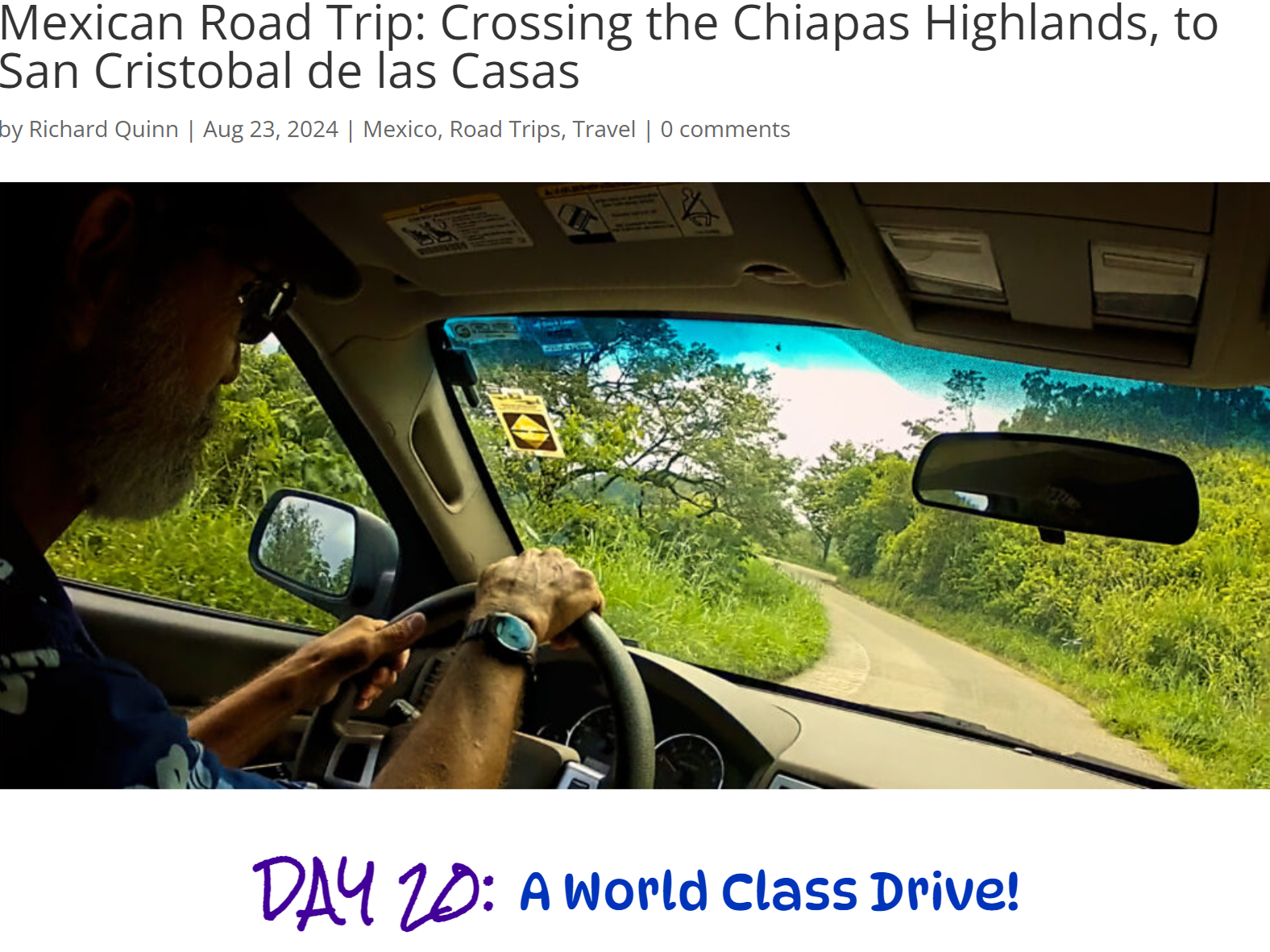

Mexican Road Trip: Crossing the Chiapas Highlands, to San Cristobal de las Casas

MX 199 crosses the Chiapas Highlands from Palenque to San Cristobal de las Casas. The distance is only 132 miles, but it’s 132 miles of curvy mountain roads with switchbacks, steep grades, slow trucks, and villages chock-a-block with topes and bloqueos, unofficial road blocks. Everything I read, and everything I heard, described the drive as alternatively spectacular, dangerous, and fascinating, in seemingly equal measure.

Mexican Road Trip: Cruising the Sierra Madre, from San Cristobal to Oaxaca

Today, we’d be driving as far as the city of Oaxaca, 380 miles of curves, switchbacks, and rolling hills that would require at least ten hours of our full attention, crossing the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, and entering the rugged, agave-studded landscape of the Sierra Madre de Oaxaca. If you’d like to know what that was like, read on!

Mexican Road Trip: Flashing Lights in the Rear View: Officer Plata and La Mordida

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Three Days of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in February, 2025.

Mexican Road Trip: Back to the Border: San Miguel de Allende to Eagle Pass

This post is a work in progress. Anticipated publication in March, 2025.

Southern Colonials: Merida, Campeche, and San Cristobal

Visiting the Spanish Colonial cities of Mexico is almost like traveling back in time. Narrow cobblestone streets wind between buildings, facades, and stately old mansions that date back three hundred years or more, along with beautiful plazas, parks, and soaring cathedrals, all of similar vintage.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

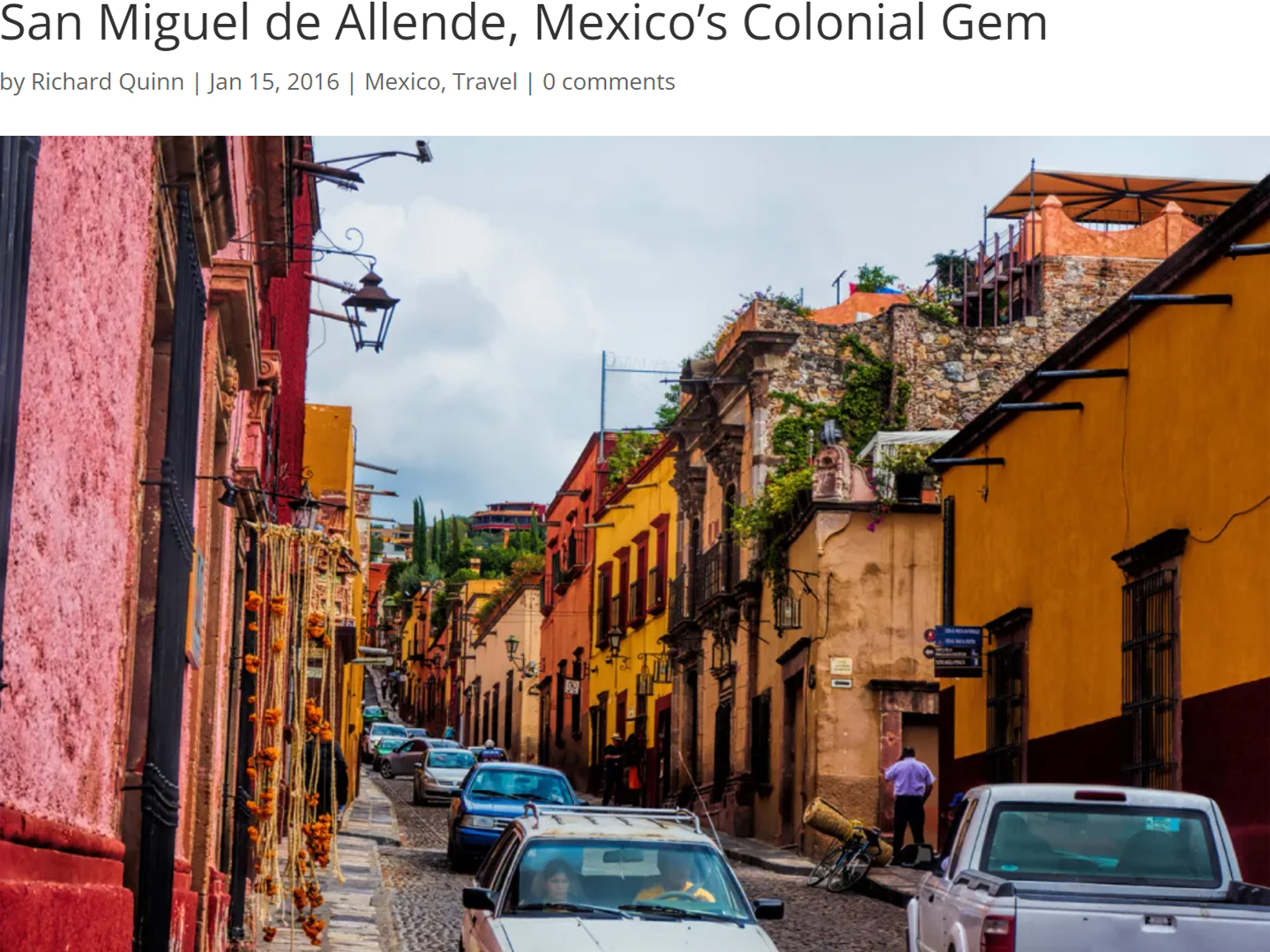

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico’s Colonial Gem

If you include the chilangos, (escapees from Mexico City), close to 20% of the population of San Miguel de Allende is from somewhere else, a figure that includes several thousand American retirees.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

Day of the Dead in San Miguel de Allende

In San Miguel de Allende, they’ve adopted a variation on the American version of Halloween and made it a part of their Day of the Dead celebration. Costumed children circle the square seeking candy hand-outs from the crowd of onlookers. It’s a wonderful, colorful parade that’s all about the treats, with no tricks!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

IN THE LAND OF THE MAYA

Palenque: Mayan City in the Hills of Chiapas

Palenque! Just hearing the name conjures images of crumbling limestone pyramids rising up out of the the jungle, of palaces and temples cloaked in mist, ornate stone carvings, colorful parrots and toucans flitting from tree to tree in the dense forest that constantly encroaches, threatening to swallow the place whole.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

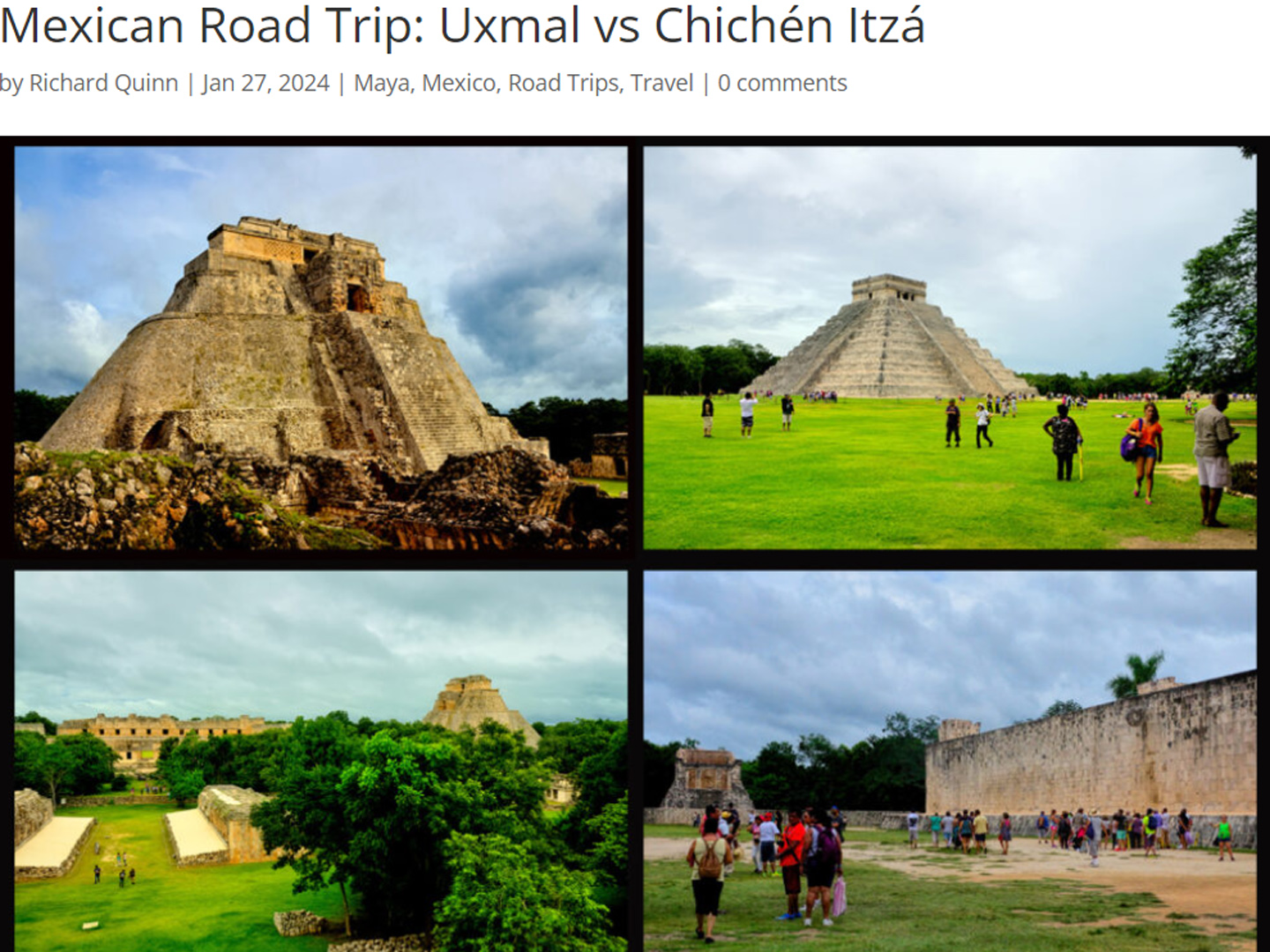

Uxmal: Architectural Perfection in the Land of the Maya

The Pyramid of the Magician is one of the most impressive monuments I’ve ever seen. There’s a powerful energy in that spot–maybe something to do with all the blood that was spilled on the altars of human sacrifice at the top of those impossibly steep steps–but more than any building or other structure at any ancient ruin I’ve ever visited, more than any demonic ancient sculpture I’ve ever seen, that pyramid at Uxmal quite frankly scared the hell out of me!

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

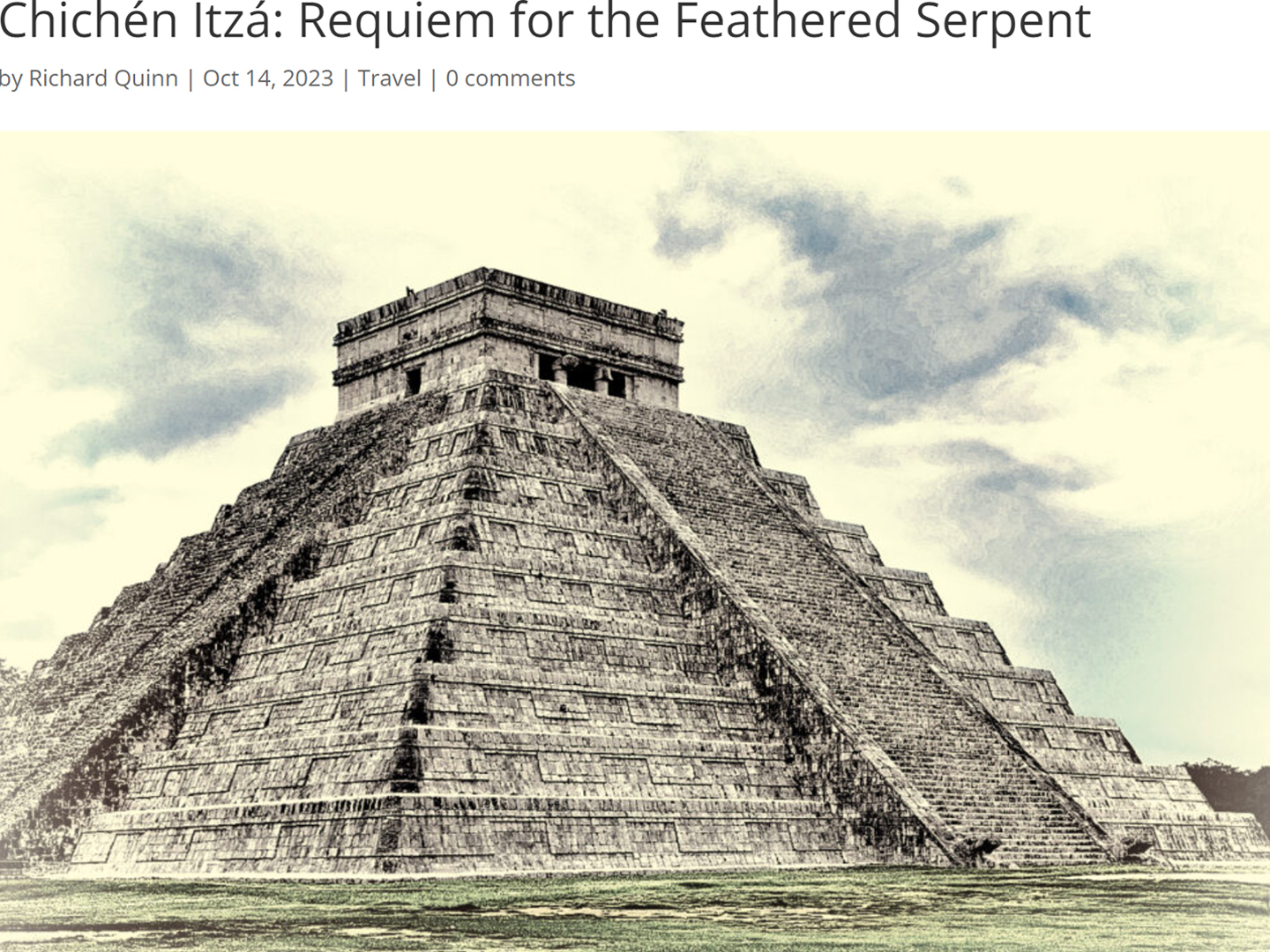

Photographer’s Assignment: Chichén Itzá

To get the best photos, arrive at the park before it opens at 8 AM. There will only be a handful of other visitors, and you’ll have the place practically all to yourself for as much as two hours! Take your time composing your perfect shot.There won’t be a single selfie stick in sight.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

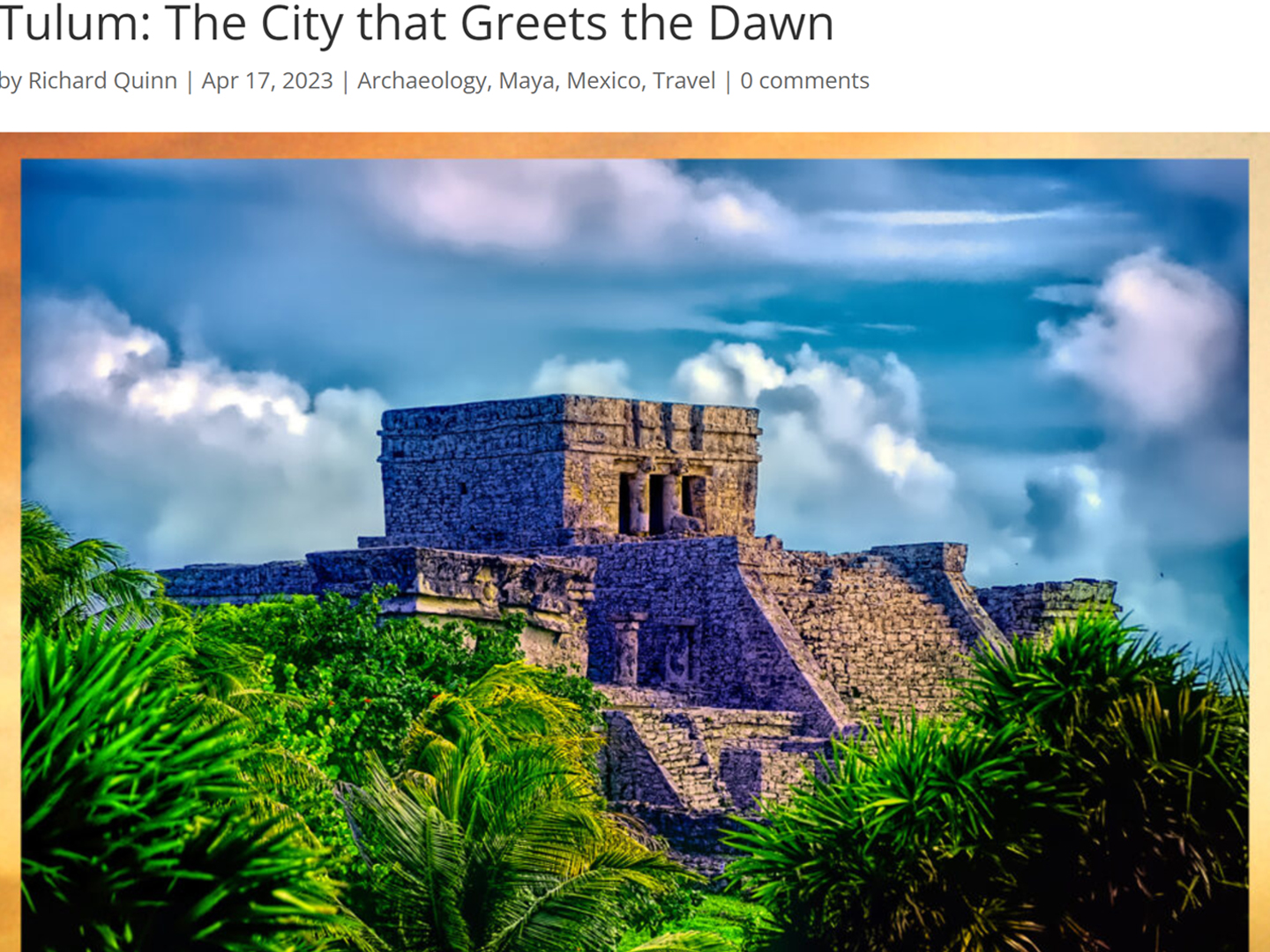

Tulum: The City that Greets the Dawn

Tulum is not all that large, as Mayan sites go, but its spectacular location, right on the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, makes it one of the best known, and definitely one of the most picturesque.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

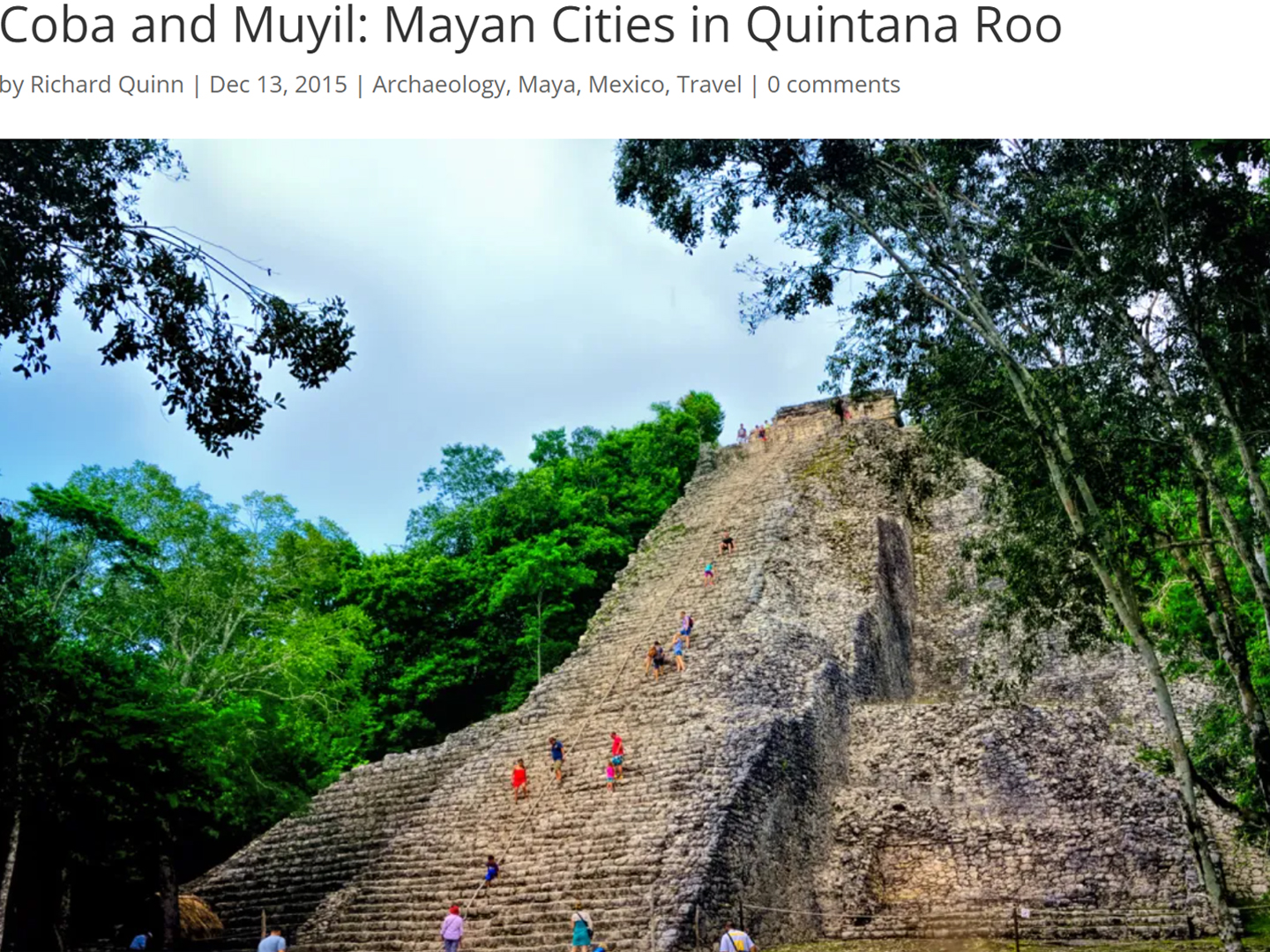

Cobá and Muyil: Mayan Cities in Quintana Roo

Cobá was a trading hub, positioned at the nexus of a network of raised stone and plaster causeways known as the sacbeob, the white roads, some of which extended for as much as 100 kilometers, connecting far-flung Mayan communities and helping to cement the influence of this powerful city.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

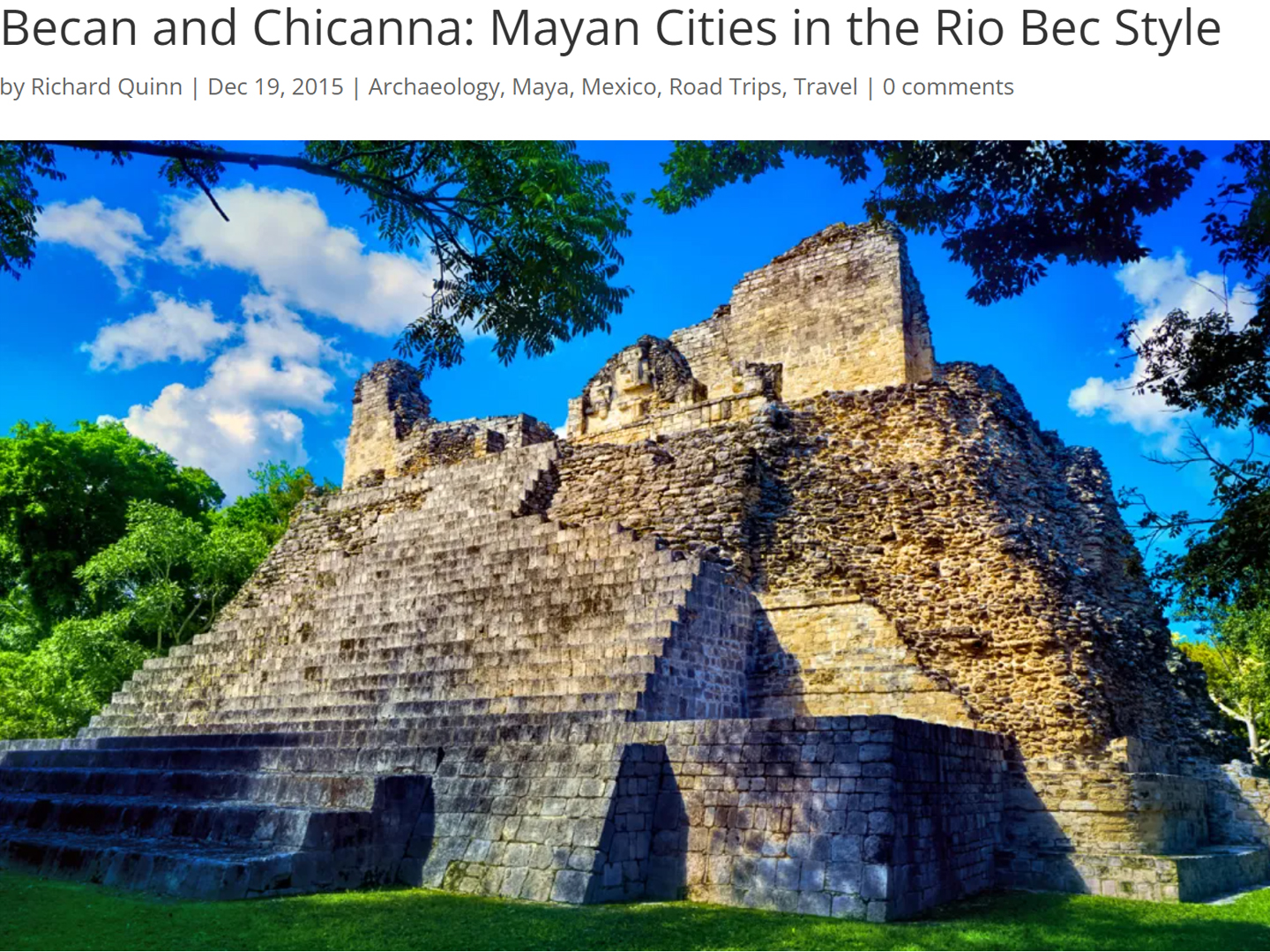

Becan and Chicanná: Mayan Cities in the Rio Bec Style

Much about the Rio Bec architectural style was based on illusion: common elements include staircases that go nowhere and serve no function, false doorways into alcoves that end in blank walls, and buildings that appear to be temples, but are actually solid structures with no interior space.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

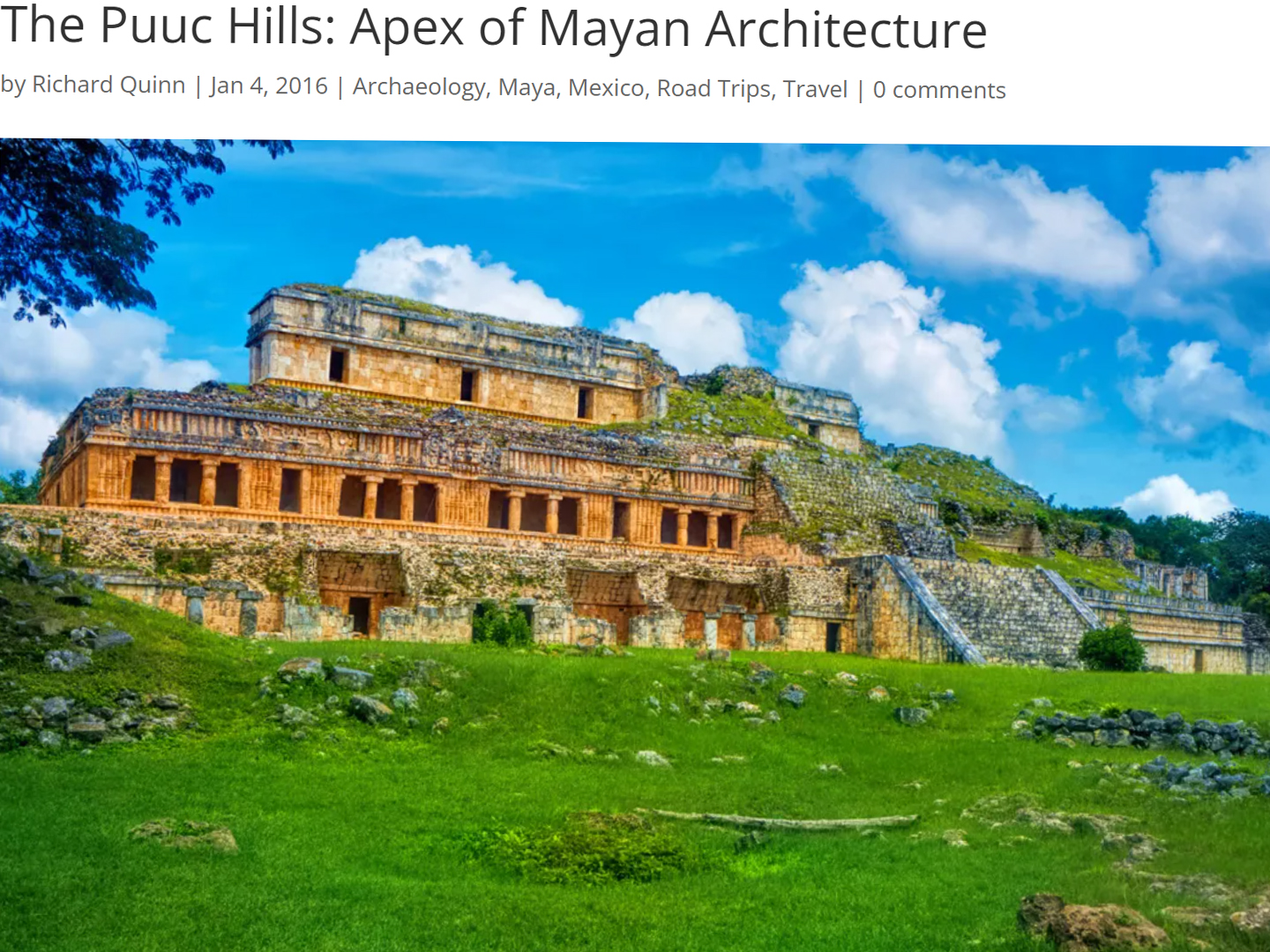

The Puuc Hills: Apex of Mayan Architecture

The Puuc style was a whole new way of building. The craftsmanship was unsurpassed, and some of the monumental structures created in this period, most notably the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal, rank among the greatest architectural achievements of all time.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

The Amazing Mayan Murals of Bonampak

Out of that handful of Mayan sites where mural paintings have survived, there is one in particular that stands head and shoulders above the rest. One very special place. Down by the Guatemalan border, in a remote corner of the Mexican State of Chiapas: a small Mayan ruin known as Bonampak.

<<CLICK to Read More!>>

A shout out to my old friend Mike Fritz (aka Mr. Whiskers), my shotgun rider on my Mexican Road Trip. “Drive to the Yucatan and See Mayan Ruins” was at the top of my post-retirement bucket list, right after “Drive the Alaska Highway and see Denali.” We checked off the whole Yucatan thing in a major way, and Mike was a heck of a good sport about it.

Road trips with old friends are the absolute best. We laugh and we laugh until we run out of breath, and laughter is good for the soul!

There’s nothing like a good road trip. Whether you’re flying solo or with your family, on a motorcycle or in an RV, across your state or across the country, the important thing is that you’re out there, away from your town, your work, your routine, meeting new people, seeing new sights, building the best kind of memories while living your life to the fullest.

Are you a veteran road tripper who loves grand vistas, or someone who’s never done it, but would love to give it a try? Either way, you should consider making the Southwestern U.S. the scene of your own next adventure.

Recent Comments